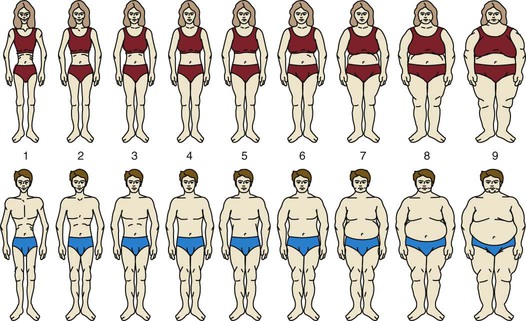

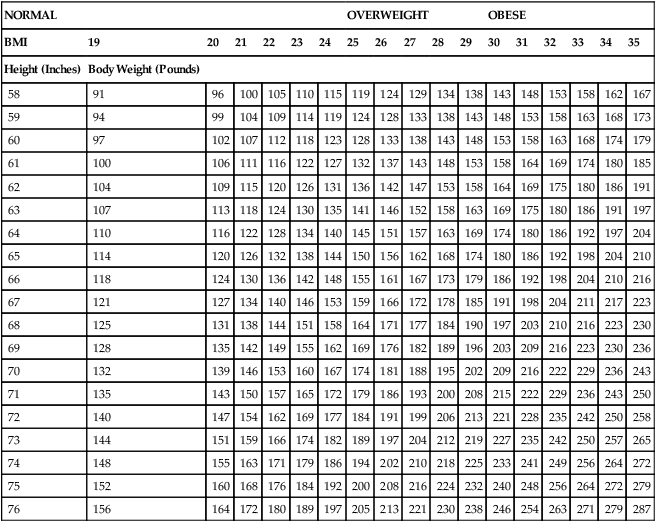

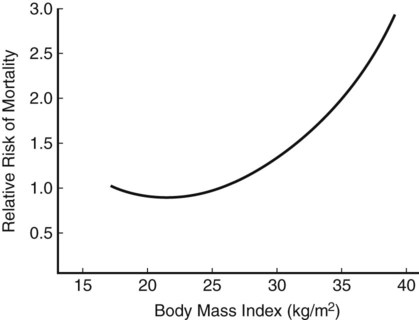

As America entered the twentieth century, things changed. There developed a preference for slenderness that has not abated. Why this change in perception of attractiveness occurred and endured is not completely clear. Probably it was the coming together of several factors. These include concerns about the effects of an increasingly sedentary lifestyle, a heightened interest in fashion, the development of the medical profession, and increased knowledge of nutrition, as well as the self-interests of various promoters who saw profit to be gained by creating an anxiety about fatness.1 Most of us weigh ourselves regularly and have a good idea of our current weight. The figure on the scale, however, does not always agree with how fat we feel. Figure 10-1 shows an example of the type of instrument that investigators use to assess differences between actual, perceived, and preferred body size. The investigator instructs the subjects to mark the figure that is most like the way they feel at that time, as well as the figure that they consider ideal for themselves. When these figures are compared with an objective assessment, regardless of their actual size, the subjects usually have greatly overestimated their size. Investigators also use figure rating scales to determine how men and women differ in size preferences; they ask you which figure is most like how you would like to be, which is most like how you currently are, and which you think is most attractive to the opposite sex. Ideally, the answers to these three questions would be closely clustered, indicating that you are fairly satisfied with your size. For men, that is usually the case. Women, however, on average consider themselves much fatter than they think is ideal. Originally it was assumed that the women’s dissatisfaction represented a desire to appear more slender and, therefore, more attractive to men. Usually, however, women’s personal ideal is thinner than the figure they think men would choose, challenging the assumption that women want to be thin to attract men. An alternative interpretation is that both men and women interpret a slender body as evidence of being in control of one’s life.2 Why is body image important? A negative body image may affect how we feel about ourselves generally: body image tends to become self-image. Furthermore, a negative body image may influence our health behaviors. We may feel defeated that because our bodies are so bad, it is not worth working hard to improve our health. At other times we may feel drawn to various kinds of risky behaviors in a frantic attempt to make our bodies more acceptable. We may strive mightily to meet the societal standards of attractiveness and thinness, but, given our individual genetic makeup, we cannot all succeed. Although humans have an awesome potential for growth and development, there are limits to the changes we can make and sustain in our body size and shape.2 If we have a healthy and positive body image, we evaluate various aspects of our bodies fairly realistically, finding some characteristics positive and others less so. Those we consider weak or unattractive, we accept in a dispassionate way, much the same way that we accept that we don’t all have beautiful singing voices or the ability to throw a great curveball. We understand that our bodies have multiple aspects, that there is more to our bodies than their size and shape. Our healthy body image is influenced by our awareness of how our bodies function and how they look. This image affects and is affected by socio-demographic factors. Body image satisfaction may be related to the degree of overweight and to psychologic distress represented by depression and low self-esteem.3 Understanding and accepting what we can and cannot expect to achieve in pursuit of the ideal body is a key to wellness. Only with this understanding can we establish goals to guide our behaviors toward health (see the Social Issues box, Dealing With Our Own Prejudices). Most of our evidence of the association between fatness and physical health comes from epidemiologic studies. Epidemiologic research investigates the distribution of disease in a population and seeks to explain associations between causative factors and the disease. This type of research usually involves thousands of subjects and may be longitudinal (i.e., involving observations over a number of years). Because it is not practical to measure fatness in these large studies, weight is usually measured instead. Weight is most meaningful when considered in relationship to height. A convenient way to determine fatness is to calculate body mass index (BMI), a value derived by dividing one’s weight in kilograms by the square of one’s height in meters (Table 10-1). This formula for BMI results in a value that correlates well with body fatness. TABLE 10-1 Data from Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. From National Institutes of Health: Aim for a healthy weight, NIH Pub. No. 05-5213, Bethesda, Md, 2005 (August), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. If we were to plot the findings of epidemiologic studies of the association of BMI and the risk of certain diseases or mortality from all causes, we would usually produce a U-shaped curve such as that shown in Figure 10-2.4 This curve means that individuals at both extremes of fatness—those very thin and those very fat—are at increased risk. Those at a more moderate fatness level have the lowest risk for the four leading causes of death in the United States: heart disease, some types of cancer, stroke, and diabetes. It is a surprise to many people that the low end of the fatness range, or underweight, shows an increased risk, which provides strong evidence that one can be too thin. It is possible that the lowest BMI in these types of curves reflects low levels not of fat but of the lean body components.4 The higher risks at the low BMI levels probably reflect some degree of body wasting, including lean body mass, possibly caused by smoking or the effects of disease. To understand the effect of fat on mortality, we need to measure body composition (fat and lean) and not rely on weight alone. Although the factors contributing to this increased risk of extremely low weight are not completely clear, they are thought to differ from the factors associated with increased risk of heavy individuals. As research has extended beyond merely relating BMI to mortality risk, we have become aware that, between extreme emaciation and great obesity, just knowing how fat a person is doesn’t tell us much about their health. If we consider how the body fat is distributed, we can improve our understanding. Without knowing the individual’s total fatness or BMI, we can still make fat-mediated predictions about health risk. Higher levels of body fat around the waist seem to be more dangerous than fat in the buttocks and thighs. Fat located in the abdominal area is called visceral fat and seems to be especially related to risk. People with high levels of visceral fat are prone to a cluster of metabolic risk factors, including high blood pressure (hypertension of ≥130/85 mm Hg); low level high-density lipoproteins (men <40 mg/dL; women <50 mg/dL); elevated triglycerides (≥150 mg/dL); and impaired fasting glucose.5 When three or more of these criteria are present, the condition is referred to as the metabolic syndrome.5 TABLE 10-2 POTENTIAL HEALTH CONCERNS ASSOCIATED WITH OR AT GREATER RISK FOR OBESE INDIVIDUALS Adapted from Table 1.3, p. 35, Power ML, Schulkin J: The evolution of obesity, Baltimore, MD, 2009, The Johns Hopkins University Press. Does losing weight make health risks go away? And what about weight gain? We don’t have strong evidence that weight loss reduces health risk. The literature is mixed about the long-term health effects of weight loss; some epidemiologic studies show increased risks following weight loss, whereas others show no effect or a diminished risk.6 Important factors seem to be whether the weight was lost in response to a voluntary effort, the health condition of the person initially, and the pattern of weight changes (many gains and losses, one sustained loss, or other patterns). One issue of contemporary concern is the effect of repeated or chronic dieting on risk. Given our cultural concern about fatness and the extremely limited success of most weight-loss attempts, there is a high likelihood that an overweight or obese adult will have tried to lose weight many times. Is it possible that some of the observed negative effects of obesity are really the outcomes of a lifetime of unsuccessful dieting? Although animal studies and some limited observations of humans support this hypothesis, reviews of the evidence conclude the risks were not strong enough to justify discouraging people from making repeated attempts to lose weight6 (see the Personal Perspectives box, A Work in Progress). For many years investigators have searched for a psychopathology that would fit most obese people and would help explain their fatness. Their efforts failed, for although a minority of overweight people suffer from a variety of mental health problems, no set of psychologic problems typical of obesity has been identified.8 Our culture’s extreme stigma against fatness extracts a tremendous toll on people who are obese. Social, economic, and other types of discrimination against obese people are widely practiced. This may lead to impaired self-image and feelings of inferiority, which in turn may contribute to social isolation and depression. Some people feel so guilty about their fatness that they hide away and put their lives on hold until they can achieve slenderness.

Management of Body Composition

Body Composition, Body Image, and Culture

Body Image

Body Perception

Body Image: Illusions versus Reality

Body Preferences: Gender Concerns

Body Acceptance: A Key to Wellness

Management of Body Fat Composition

Association of Body Fatness with Health

Physical Health

NORMAL

OVERWEIGHT

OBESE

BMI

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

Height (Inches)

Body Weight (Pounds)

58

91

96

100

105

110

115

119

124

129

134

138

143

148

153

158

162

167

59

94

99

104

109

114

119

124

128

133

138

143

148

153

158

163

168

173

60

97

102

107

112

118

123

128

133

138

143

148

153

158

163

168

174

179

61

100

106

111

116

122

127

132

137

143

148

153

158

164

169

174

180

185

62

104

109

115

120

126

131

136

142

147

153

158

164

169

175

180

186

191

63

107

113

118

124

130

135

141

146

152

158

163

169

175

180

186

191

197

64

110

116

122

128

134

140

145

151

157

163

169

174

180

186

192

197

204

65

114

120

126

132

138

144

150

156

162

168

174

180

186

192

198

204

210

66

118

124

130

136

142

148

155

161

167

173

179

186

192

198

204

210

216

67

121

127

134

140

146

153

159

166

172

178

185

191

198

204

211

217

223

68

125

131

138

144

151

158

164

171

177

184

190

197

203

210

216

223

230

69

128

135

142

149

155

162

169

176

182

189

196

203

209

216

223

230

236

70

132

139

146

153

160

167

174

181

188

195

202

209

216

222

229

236

243

71

135

143

150

157

165

172

179

186

193

200

208

215

222

229

236

243

250

72

140

147

154

162

169

177

184

191

199

206

213

221

228

235

242

250

258

73

144

151

159

166

174

182

189

197

204

212

219

227

235

242

250

257

265

74

148

155

163

171

179

186

194

202

210

218

225

233

241

249

256

264

272

75

152

160

168

176

184

192

200

208

216

224

232

240

248

256

264

272

279

76

156

164

172

180

189

197

205

213

221

230

238

246

254

263

271

279

287

Obesity and Physical Health

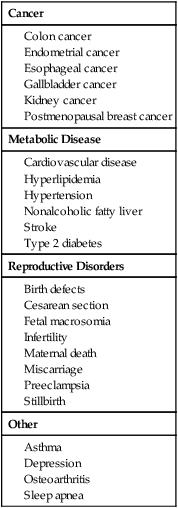

![]() Obesity also increases the risk of health conditions that affect well-being but aren’t usually life threatening. Examples include menstrual irregularities, infertility, gallbladder disease, and some types of arthritis. Table 10-2 lists health issues for which obesity increases risk.

Obesity also increases the risk of health conditions that affect well-being but aren’t usually life threatening. Examples include menstrual irregularities, infertility, gallbladder disease, and some types of arthritis. Table 10-2 lists health issues for which obesity increases risk.

Cancer

Metabolic Disease

Reproductive Disorders

Other

![]() Unanswered questions.

Unanswered questions.

![]() Most epidemiologic studies include only initial weight, final weight, and mortality. This level of evidence is inadequate to illustrate the effect of sustained weight changes. One of the studies attempting to provide the needed information is the Nurses’ Health Study, which has monitored for 20 years the health of more than 100,000 female nurses. This study shows that nurses who gained 22 pounds or more after the age of 18 had increased mortality risk in middle age.7

Most epidemiologic studies include only initial weight, final weight, and mortality. This level of evidence is inadequate to illustrate the effect of sustained weight changes. One of the studies attempting to provide the needed information is the Nurses’ Health Study, which has monitored for 20 years the health of more than 100,000 female nurses. This study shows that nurses who gained 22 pounds or more after the age of 18 had increased mortality risk in middle age.7

Chronic dieting and risk.

Obesity and Emotional/Social Health

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Management of Body Composition

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access