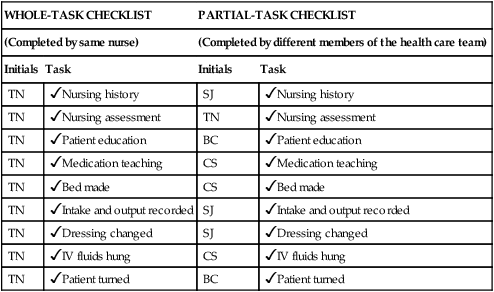

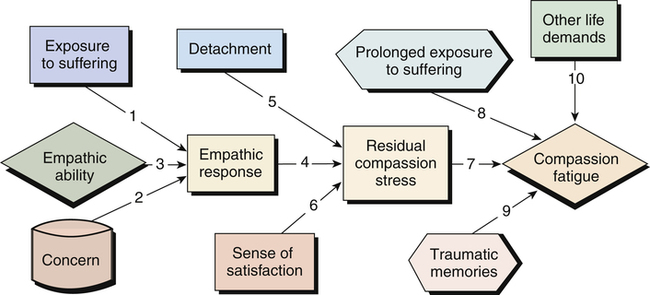

After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Compare and contrast the phases of reality shock with the phases of transition shock. 2. Differentiate between the novice nurse and the expert professional nurse. 3. Design strategies to ease the transition from novice nurse to professional nurse. 4. Differentiate between compassion fatigue and burnout. 5. Make the transition from novice nurse to professional nurse. The merging of school values with those of the workplace. The gradual decline of compassion over time as a result of caregivers being exposed to events that have traumatized their patients. Horizontal hostility (also known as lateral hostility) “A consistent (hidden) pattern of behavior designed to control, diminish, or devalue another peer [or group] that creates a risk to health and/or safety” (Hinchberger, 2009). Bullying, negative insinuations, undermining, and exclusion are examples. A mutual interactive method of learning in which a knowledgeable nurse inspires and encourages a novice nurse. A nurse who is entering the professional workplace for the first time; usually occurs from the point of graduation until competencies required by the profession are achieved. An experienced professional nurse who serves as a mentor and assists with socialization of the novice nurse. Occurs when a person prepares for a profession, enters the profession, and then finds that he or she is not prepared. A person who serves as an example of what constitutes a competent professional nurse. The nurturing, acceptance, and integration of a person into the profession of nursing; the identification of a person with the profession of nursing. Moving from one role, setting, or level of competency in nursing to another; change. the abrupt shock associated with moving from student to professional nurse associated with doubt, confusion, disorientation, and loss (Duchscher, 2009). Sexual harassment and abusive acts from patients that can be physical, verbal, and emotional and lead to a hostile work environment. It has been suggested that identifying workplace violence is difficult due to its subjectivity by the recipient. Additional resources are available online at: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cherry/ Vignette Questions to Consider While Reading This Chapter 1. What could educators incorporate into the curriculum to decrease the “reality shock” of transition from student to professional nurse? 3. What strategies should novice nurses use to gain self-esteem and prove themselves capable of having the required skills while still needing help with specific tasks and skills that come with experience? 5. What could orientation for new employees include to help novice nurses be proactive in preventing or reacting to violence at work? According to Webster (www.merriam-webster.com), transition is defined as “change” or the “passage from one state, place, stage, or subject to another.” As nurses prepare to enter the profession and make the transition from student to registered nurse (RN), they move not only from one role to another, but also from the school or university setting to the workplace. Transition is a complicated process during which many changes may be happening at once. The novice nurse tries to juggle all these changes while continuing a life outside of nursing (e.g., as mother, father, husband, wife, daughter, son, active church leader, or community volunteer). Novice nurses are described as feeling as though they have changed from the most intelligent students in nursing school to the most incompetent nurses in the professional practice environment (Smith, 2007). When the expert student moves into the novice nurse role, uncertainty takes over, and the support of classmates and the nursing instructors is gone. This time marks the end of one era as a student and the beginning of a new era in a nursing career. Novice nurses often suffer what Kramer (1974) describes as reality shock, which is the result of inconsistencies between the academic world and the world of work. Reality shock occurs in novice nurses when they become aware of the inconsistency between the actual world of nursing and that of nursing school. As the novice nurse enters the new profession, reality shock begins. The excitement of passing the licensure examination quickly fades in the struggle to move from the student to the staff nurse role. Reality shock leads to stress (Smith, 2007), which can threaten the well-being of new nurses and result in physical illness and mental exhaustion, leading to disillusionment with their career (Hertel, 2009) and ultimately absenteeism and turnover (Jennings, 2008). Cho and colleagues (2012) found that the probability of novice nurses staying in their first nursing job for 1, 2, and 3 years was 0.823, 0.666, and 0.537, respectively. “Dissatisfaction with interpersonal relationships, work content, and physical work environment” were shown to be contributors to leaving the first job (Cho et al, 2012, p. 63). The Institute of Medicine report recognized the need to assist novice nurses in their transition to practice (2011). There are four phases of reality shock: honeymoon, shock or rejection, recovery, and resolution (Kramer, 1974). Then orientation is over, and the novice nurse begins work on his or her assigned unit. This nurse receives daily assignments and begins the tasks. “But wait. I’ve only observed other nurses hanging blood. Where is my instructor?” Now the shock or rejection phase comes into play. The nurse comes into contact with conflicting viewpoints and different ways of performing skills, but lacks the security of having an expert available to explain uncertain or gray areas. “As Registered Nurses, they found they have to ‘think on their feet’ without the ‘comfort blanket’ of student status” (Standing, 2007). The security of saying, “I am just the student nurse,” is no longer valid. During this phase, the novice nurse may be frightened or react by forming a hard, cold shell around himself or herself. Vague feelings of discomfort are experienced, and the inexperienced nurse often wonders whether the other nurses care about the patients. After going home from a shift, the new nurse may experience feelings of rejection and a sense of lack of accomplishment. The novice nurse may reject the new environment and have a preoccupation with the past when he or she was in school. A need to contact former instructors, call schoolmates, or visit the nursing school may occur. Others may reject their school values and adopt the values of the organization. In this way, they may experience less conflict (Kramer, 1974); however, there are drawbacks to this approach as well. During this phase, Kramer (1974) suggests that novice nurses must ask themselves two important questions: 1. What must I do to become the kind of nurse I want to be? 2. What must I do so that my nursing contributes to humankind and society? Many nurses choose to go “native” (Kramer, 1974, p. 161). That is, they decide they cannot fight the experienced nurses or the administration, thus they adopt the ways of least resistance. These nurses may mimic other nurses on the unit and take shortcuts, such as administering medications without knowing their action and side effects and the associated nursing responsibilities. Others choose to “run away.” They find the real world too difficult. These new nurses may choose another occupation or return to graduate school to prepare for a career in nursing education to teach others their “values in nursing.” Perkins (2010) describes wondering why she was tolerating poor working conditions, but states she found little hope in finding a better environment in other hospitals. This resulted in beginning graduate school after 8 months of practice. These nurses bottle up conflict until they become burned out. Kramer (1974) describes the appearance of these nurses as having the look of being chronically constipated. In this situation, patients may feel compelled to nurse their nurse. Inexperienced nurses may become burned out because they assume full patient loads and varied responsibilities in a short period of time (Henderson and Njuru, 2007). High nurse-to-patient ratios with scant ancillary support staff make for an impossible transition (Perkins, 2010), leading to burnout. When there is a chasm between the novice nurse’s expectations and the desire of the health care facility to meet these expectations, this void is fundamental to burnout (Fearon and Nicol, 2011). Some common symptoms of burnout include extreme fatigue, negativity in personal relationships, difficulty sleeping, mood swings, anxiety, poor work quality, depression, and alcohol abuse (Mayo Clinic, 2012). The more intelligent, hard-working nurses are the most prone to burnout, but if you exhibit these symptoms, remember that they can be reduced. Not to be confused with burnout or transference, compassion fatigue is the gradual decline of compassion over time as a result of caregivers being exposed to events that have traumatized their patients (Figley, 2001). Even experienced nurses, who commonly have a great deal of empathy working in environments where patients suffer trauma, may develop a reaction in which they have a decrease in compassion. Exposure to traumatic events experienced by their patients may result in compassion fatigue. Nurses who work in emotionally charged environments, such as hospice, emergency departments, and mental health settings, are likely to experience this reaction. Intensive ongoing losses such as those in oncology care make nurses vulnerable to burnout and compassion fatigue (Potter et al, 2010). The balance between caring too much or too little is difficult to achieve (Lester, 2010). Nursing students are also at risk for compassion fatigue and need to identify their stress triggers (Sheppard, 2011). The compassion fatigue process is depicted in Figure 24-1. Zerwekh and Claborn (2009) suggest completing a reality shock inventory to make nurses more aware of how they feel about themselves and the situation at present. The higher the score, the better the attitude. It might be helpful to take the test at different times throughout one’s career or when trying to decide whether a career change would be advantageous (Box 24-1). Many nurses are familiar with the term culture shock. Culture shock occurs when people are immersed into a culture different from their own with norms that are unfamiliar and uncomfortable. This is exactly what happens in reality shock. Academia stresses patient-centered nursing, whereas the workforce stresses management of tasks and timelines, which may lead to feelings of failure because of the inability to provide holistic care. Novice nurses who require additional time to complete skills/tasks are often ridiculed rather than supported (Norris, 2010). First, consider how students were taught to think in nursing school. When they prepared a care plan that took all night to complete, how were they to view the patient? Nursing schools teach holistic nursing, or rather “wholistic” nursing, in which students are taught to look at the patient as a whole and even incorporate the family and significant other into the care plan. However, in the real world, nurses may function with a partial-person approach. Different members of the health care team divide the patient care into parts. This type of health care, in which different members of the health care team divide the patient care into parts, is termed the partial-task system and only requires partial knowledge (Kramer, 1974). For instance, one nurse may be assigned to administer all medications, whereas another may be assigned to dressing changes. The nursing assistant aids with personal hygiene and grooming; the physical therapist provides range-of-motion exercises, and the respiratory therapist teaches pulmonary hygiene techniques. There are many other nursing care delivery models in which the role of the RN varies considerably. The partial-task system just described is also congruent with the model known as “functional nursing,” which places a high emphasis on completion of tasks. It is an efficient method when working with large numbers of patients, but the nurse cannot provide holistic care within such a system (Huber, 2010). With functional nursing and the partial-task system, the nurse is seen as only part of the care picture, but the RN is the central organizer and responsible for follow-through on all care given by other members. This type of system is popular because fewer professional staff members are required, and it is frequently used on the evening and night shifts when staffing is considerably less. This type of partial-task system encourages loyalty to the organization because it forces the nurse to focus on task completion and productivity. The nurse ensures that all tasks are carried out, but is not the sole provider of care. A simple checkmark often assesses quality, with initials being placed by completed tasks (Box 24-2). Most novice nurses are more comfortable with the whole-task system because it is more consistent with what they were taught in school. The whole-task system requires complete knowledge and encourages loyalty to the profession. The nurse provides total patient care, which incorporates physical, emotional, spiritual, and cultural components. The model of nursing care consistent with the whole-task system is primary nursing, in which the nurse is responsible for all the needs of the patient (Huber, 2010). This model provides increased satisfaction for the patient and the nurse. However, because of the need to use an increasing number of lower-salaried employees and the shortage of RNs, few institutions continue to use this model. Another inconsistency between the school and work environment is the means of evaluation (Kramer, 1974). The school environment evaluates care from the “correct step” aspect, whereas the evaluation phase in the work environment is based on whether components of care were completed according to established policies and procedures. Were all the steps carried out in a logical, correct, and efficient way? This is exemplified in Case Study 24-2. The transition from student to professional nurse is difficult, and changes in the health care environment have only added to the strain. Socialization of the novice nurse is key to his or her ability to transition or just “survive” at the clinical level (Mooney, 2007). Often new nurses are greeted with open hostility rather than being welcomed (Adler, 2009). Nursing administrators may not support the novices’ need to learn and may expect them to perform at the same level as experienced nurses. Unfortunately, the novice nurse may become bewildered and discouraged.

Making the Transition from Student to Professional Nurse

Chapter Overview

Reality Shock

Shock (Rejection) Phase

Natives

Runaways

Burned Out

Compassion Fatigue

Resolution Phase

Causes of Reality Shock

Partial-Task versus Whole-Task System

Evaluation Methods

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Nursing history

Nursing history Nursing history

Nursing history Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment Patient education

Patient education Patient education

Patient education Medication teaching

Medication teaching Medication teaching

Medication teaching Bed made

Bed made Bed made

Bed made Intake and output recorded

Intake and output recorded Intake and output recorded

Intake and output recorded Dressing changed

Dressing changed Dressing changed

Dressing changed IV fluids hung

IV fluids hung IV fluids hung

IV fluids hung Patient turned

Patient turned Patient turned

Patient turned