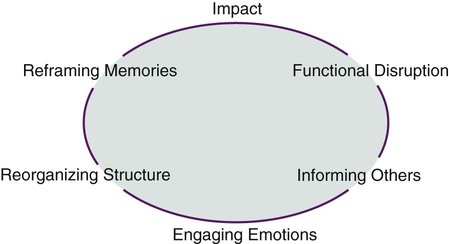

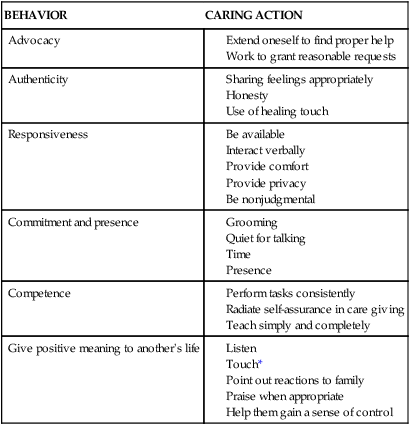

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Compare and contrast the needs of elders in response to varying types of losses. 2. Differentiate different types of grief and the needs of the griever. 3. Discuss the attributes of the nurse that are needed to provide the highest quality of care to those experiencing loss or death. 4. Discuss the benefits and limitations of the available conceptual frameworks for dying and grieving. 5. Identify aspects of palliative care in which there is a special need to work within the cultural boundaries. 6. Develop interventions that will enhance coping and the reestablishment of equilibrium within the family. 7. Differentiate among the types of advance directives, and explain the role and responsibilities of the nurse as they relate to each of them. 8. Determine the legal status of Death with Dignity laws for the state in which the nurse practices. 9. Discuss the pros and cons of active and passive euthanasia. Researchers have tried for years to understand the grieving process, resulting in a number of proposed models and theories to explain and predict the human response. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross is best known for describing what have become known as the [emotional] stages of dying (1969). Other notable theorists looked specifically at the grieving process; these include Rando (1995), Worden (2009), Corr (2000), and Doka (1989). The models evolved between the 1960s and 1990s and strongly influence what nurses, physicians, other health care professionals, and society in general have been taught about grieving and dying. Although intended to describe physical death and related grief, we propose that these same models can be applied to grieving of any of the losses in the lives of older adults that are considered significant or meaningful, from anticipating the loss of self to that of others. Regardless of the theorist, grief is described as a process that has a beginning with physical and psychological manifestations; a middle, when the griever’s day-to-day functioning may be affected; and an end, when the individual emerges refocused and has adjusted to the loss. Influenced by esteemed psychiatrist Avery Weisman (1979) and building on the work of thanatological scholars and that of the nurse Barbara Giacquinta (1977), a systems approach is proposed to both understand the grieving process and design nursing interventions to provide comfort and support to those who have experienced or are experiencing a loss. In the Loss Response Model, the family and the person as grievers are viewed as a system that strives to maintain equilibrium (Figure 23-1). A systems approach lends itself to an understandable and usable model of the grieving process from which nursing interventions are easily developed. If the loss is certain but the timing is either uncertain or it does not occur when or as expected, those awaiting the loss may become irritable or impatient, not because they want the loss to occur but in response to the emotional ups and downs of the waiting. Glaser and Strauss (1968) describe what they call an interruption in the sentimental order of a nursing unit when this occurs—no one quite knows how to behave. Family and friends as well as professional grievers, such as nurses, usually deal much more easily with known losses at a known time or in a set manner (Glaser and Strauss, 1968). Some individuals feel more in control of the situation because anticipatory grief facilitates planning and preparation for death by saying goodbyes in special ways (Zilberfein, 1999). Anticipatory grief also can result in the phenomenon of premature detachment from an individual who is dying or detachment of the dying person from the environment. Pattison (1977) calls this premature withdrawal of others sociological death and premature withdrawal from loved ones prior to death psychological death. In either case, the person who is dying is no longer involved in day-to-day activities of living and essentially suffers a premature death. Grieving takes time, sometimes much longer than anyone anticipates. In most cases, the acute grief comes to some resolution as memories are reframed. For many, there is a lingering sadness referred to as shadow grief (Horacek, 1991). It may temporarily inhibit some activity but is considered a normal response. The intermittent pain of grief may be triggered by anniversary dates (birthdays, holidays, anniversaries) or by sensory stimuli, such as the smell of perfume, a color, or a sound (Box 23-1). For the survivors of major tragedies, war, or crime, the “shadows” may never completely go away. Persons may deal with this response to their loss in many different ways. Each year, individuals visit the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., to remember and leave items that connect them to those who have died. Similarly, individuals make pilgrimages to the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, praying and placing prayer papers in the crevices of the wall. In Mexico, the annual holiday “Day of the Dead” is a time when people visit the graves of their family members, leave food, grieve anew, and feel a renewed sense of connection with those who have died before them. These practices may instead be considered healthy and restorative for those who participate. Other chronic grief is a form of complicated grieving. Some chronic grief is more than that of shadow and crosses over the boundary to what we call complicated grief. It has been thought that complicated grief begins with chronic, uncomplicated grief but that obstacles interfere with its evolution toward adjustment, so that the reestablishment of equilibrium is distrubed. The memories resist being reframed for many months and even years. Issues of guilt, anger, and ambivalence toward the individual who has died are factors that will impede the grieving process until these issues are resolved. Reactions are exaggerated and memories are experienced as recurrent acute grief—repeatedly, months and years later. Signs of possible complicated grief include excessive and irrational anger, outbursts in social settings, and insomnia that lingers for an extended time or surfaces months or years later. The grief may also trigger a major depressive episode. Cognitive difficulties that accompany a major depressive episode may be misinterpreted as dementia in the very frail and result in inappropriate treatment. This type of grief requires the professional intervention of a grief counselor, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, or a psychologist who is skilled in helping grieving elders (Corless, 2006). The person whose loss cannot be openly acknowledged or publicly mourned experiences what is called disenfranchised or unspeakable grief. The grief is socially disallowed or unsupported (Doka, 1989). The person does not have a socially recognized right to be perceived or function as a bereaved person. In other words, a relationship is not recognized; the loss is not sanctioned; or the griever is not recognized. Disenfranchised grief has frequently been associated with domestic partnerships (e.g., same-sexed partner) and marriages (e.g., bi-racial), in which the family of the deceased does not acknowledge the partner, or in secret relationships (e.g., extra-marital), in which the involved party cannot tell others of the meaning or depth of the attachment. Disenfranchised grief can also occur in situations of family discord, in which a member of the family is considered the “black sheep.” An unspeakable grief may follow a suicide or death due to AIDS. The person in late life can experience disenfranchised grief when family or friends do not understand the full meaning, for example, of a retiree’s retirement, the death of a pet, or gradual losses caused by chronic conditions. Families coping with a member who has Alzheimer’s disease may also experience disenfranchised grief when others perceive the death of the elder as a blessing and fail to support the griever or caregiver who has struggled for years with anticipatory grief and now must cope with the actual death. In the language of the Loss Response Model, coping with loss is the ability to move from a state of chaos and disequilibrium to one of reorder, equilibrium, and peace. Many factors affect the ability to cope with loss and grief (Box 23-2). • Confront realities, and take appropriate action • Have good communication with others • Seek and use constructive help The goal of the grief assessment is to differentiate those who are likely to cope effectively from those who are less likely so that appropriate interventions can be planned (Box 23-3). A grief assessment is based on knowledge of the grieving process. Data are obtained through observation of behavior of the individual in the context of gender and culture (Goldstein et al., 2004). Reminiscence is often helpful in creating new memories (see Chapter 6). Listening to the story, endlessly repeated, is difficult to do. The story is likely to change with each retelling as new memories or perspectives develop. Reminiscence is a means by which denial can fall by the wayside and allow reality of the loss to filter slowly into the conscious mind. Reminiscence helps the griever acknowledge that the loss is indeed real and that life can go on, even though the future may be experienced in a different way. The nurse’s role is also as an advocate who displays the behavioral qualities of responsiveness, authenticity, commitment, and competence, that is, caring (Krohn, 1998) (Table 23-1). TABLE 23-1 *The appropriateness of the use of touch varies greatly by culture (see Chapter 5). From Krohn B: Geriatric Nursing 19:276, 1998. Weisman (1979) described the work of health care professionals related to grief as “countercoping.” Although he was speaking of working with people with cancer, it is equally applicable to working with people who are grieving for other losses. “Countercoping is like counterpoint in music, which blends melodies together into a basic harmony. The patient copes; the therapist [nurse] countercopes; together they work out a better fit” (Weisman, 1979, p. 109). Weisman suggests four specific types of interventions or countercoping strategies: (1) clarification and control, (2) collaboration, (3) directed relief, and (4) cooling off. Before the 1900s, most women and men died at home. Women died during childbirth, and men died of unknown causes. During times of war, most men died in battle or from battle-associated injuries. The life expectancy at birth in 1900 was 46.3 years for men and 48.3 years for women (United States). Now both men and women live well into their 70s and beyond (see Chapter 1). While most people prefer to die at home, they still most often die in acute and long-term care settings, although the number of home deaths is increasing.

Loss, Death, and Palliative Care

Grief Work

A Loss Response Model

Types of Grief

Anticipatory Grief

Chronic Grief

Complicated Grief

Disenfranchised Grief

Factors Affecting Coping with Loss

Promoting Healthy Aging: Implications for Gerontological Nursing

Assessment

Interventions

Loss Response Model

BEHAVIOR

CARING ACTION

Advocacy

Authenticity

Responsiveness

Commitment and presence

Competence

Give positive meaning to another’s life

Countercoping

Dying and Death

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access