Nurses sensitive to normal growth patterns as affected by genetics and environmental influences can help families to understand the growth curves of their children. Height, weight, and head circumferences are used with the standard growth charts from the National Center for Health Statistics to monitor growth (available at www.cdc.gov/growthcharts). See Chapter 14 for a detailed description of clinical nutrition assessment procedures. Ellen Satter, a registered dietitian and therapist, describes the feeding relationship as the interactions or patterns of behaviors that surround food preparation and consumption within a family. This description reveals the contextual nature of food preparation and consumption. Her advice to parents and caregivers is about “the division of responsibility. You are responsible for what your child is offered to eat, but he is responsible for how much of it he eats and even whether he eats.”1 Adults are responsible for not only what meals are offered but also when meals are offered. Regularity of mealtimes at home—breakfast and dinner—helps support success at school. Breakfast supplies energy in the morning for school learning (see the Teaching Tool box, What’s the Best Breakfast?); dinner supports the ability to complete homework, study, and relax before bedtime. Most children eat lunch away from home and either bring a prepared lunch from home or purchase meals through a school lunch program. (School lunches are discussed later in this chapter under the heading “Community Supports.”) Snacks boost daily nutrient intake; for children whose energy and general dietary intake are adequate, snacks may sometimes include sweets such as cookies and even an occasional candy bar. A common myth is that sugar makes children hyperactive, yet studies have shown no convincing evidence that consumption of sugar causes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. High-sugar-containing foods, however, can displace more nutritious foods and contribute to nutrient deficiencies (such as of calcium and dietary fiber) or excessive caloric and dietary fat intake. Of significant concern is childhood excess adiposity or overweight.2 (See “Overcoming Barriers” later in this chapter.) No food should be forbidden; frequency and quantity should be the guides. Although adults may have predominant influence over the eating behaviors of children, another primary influence for some children is television. The influence of TV commercials has been studied extensively and is most often condemned as negatively influencing children’s food choices. In addition, watching television when eating family meals appears to affect the types of foods served, which results in consumption of foods higher in fat and lower in fiber. This possibly reflects the categories of foods most often advertised on television.3 Parents and caregivers can watch television with their children to assess the type of products advertised and then discuss their nutritional value. As more healthful products are marketed, even if targeted at adults, acceptance by children may increase. Occasional treats of advertised products may lessen their appeal if children are accustomed to high-quality snacks and meals. The Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) for daily dietary fat intake recommends about 30% kcal intake. This level of dietary fat intake may also assist with obesity prevention and emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and complex carbohydrates. It is easier to enjoy whole foods that are naturally low in fat throughout childhood than to convert one’s eating style as an adult. Other AMDR include for carbohydrates 45% to 65% kcal; for protein 5% to 20% kcal for young children and 10% to 30% kcal for older children; added sugars should not exceed 25% of total calories; and adequate intake dietary fiber of 19 g/day for children 1 to 3 years, 25 g/day for 4 to 8 years, 31 g/day boys 9 to 13 years, and 26 g/day girls 9 to 13 years.2 Despite national dietary recommendations, trends in children’s total energy intake are increasing. Although calories increased, total intake of milk, vegetable, soups, breads, grains, and eggs decreased, and intake of fruits, fruit juices, sweetened beverages, poultry, and cheese increased. When food groups are considered, about 16% of U.S. children did not meet any food group recommendations, whereas only 1% consumed recommended amounts for all food groups. Approximately two-thirds of U.S. children do not consume suggested servings of fruits and vegetables. Consumption of whole grains is extremely low, with consumption of two or more servings of whole grains daily by less than 13% of children. Those who did meet dietary recommendations had intakes that were high in fat. Consider that for some children, their principal vegetable is french fries. These findings indicate that nutrition education is still needed for parents and their children. (The Cultural Considerations box, Child Health Education for Foreign-Born Parents, offers suggestions for educating foreign-born parents about their child’s health.) Health professionals need to use careful wording when discussing nutrient restriction or reduction for children. Several infants have developed failure to thrive, not because of neglect or lack of food but because of parental over vigilance about fat, both dietary and body.4 Usually referred to as “toddlerhood,” the age span of 1 to 3 years old is a busy time for young children. They are dealing with issues of autonomy. Often food and eating create an arena for asserting newly discovered independence. The eating relationship between parent (or caregiver) and child is forming, and adult reaction to autonomy sets the stage for future encounters.1 Consistency of mealtimes is important. Meals are best accepted when hunger, tiredness, and emotions are still controllable; an overly tired child just cannot eat. Equally important is fostering self-reliance by allowing young children to feed themselves in a manner most appropriate for their psychomotor abilities. Regardless of the messy results, attempts to self-feed provide the roots of self-empowerment crucial to overall physical and psychologic development (Figure 12-1). Growth, basal metabolic rate (BMR), and endless activity require an energy supply of 1300 kcal/day for ages 1 to 3. Protein needs increase to 16 g to meet the demands of growing muscles. For children aged 1 through 6 years, a general guideline is one fruit or vegetable serving equals one level-measuring tablespoon of fruit or vegetable per year of age. A serving of bread or cereal is equal to about one-fourth of an adult’s serving. Up to age 3, children should consume two or three 8-ounce cups of milk per day or about 16 to 24 ounces per day, and meats or meat substitutes can be offered at least twice per day.5 Caregivers should be advised that alternative milk products such as rice milk and soymilk, unless sufficiently fortified, may not provide the same quality of nutrients as animal-derived foods. This is also a prime time to introduce toddlers to a variety of foods. (See Chapter 11, Personal Perspectives Developing “Nutrition Intelligence.”) Toddlers imitate the adults around them; therefore, adults can model behavior by eating a variety of foods themselves. Clever introductions to foods are always helpful to catch the attention and appetite of toddlers. Broccoli is more than just a vegetable; cut up, it looks like little trees. Peas steamed in their pods are not just peas but green pearls waiting to be discovered. At this stage children can develop a sense of responsibility for healthful food selections. They can understand that although all foods are okay, some foods such as fruits, vegetables, and low-fat foods can be eaten more often than others. After participating in a 3-month nutrition education demonstration project to decrease cholesterol and cardiovascular risk, some of the children ages 4 to 10 reduced their kcal intake of fat by about 9% by replacing higher-fat food with lower-fat foods within the same food group. These same children also increased their overall intake of fruits, vegetables, and very-low-fat desserts. Their total calorie and nutrient intake remained appropriate.6 The years from 7 to 12 are tumultuous. Although actual growth may slow down, the body is preparing and seemingly storing up for the puberty growth spurt. Puberty may begin for girls from around age 9; boys may reach puberty in the early teen years. This prepuberty time may be reflected by weight buildup; an increase in chubbiness is not alarming if moderate eating and physical activities are maintained. Adults must be careful not to overreact, or they may plant the seeds of eating disorders. To rule out overeating, children can be asked if they are really hungry for food or whether they are only tired or thirsty. These are different sensations. A child can be reminded to “stop eating when you are full” (Figure 12-2). If hunger returns, a snack can be provided. By taking time to consider these sensations, children can stay in touch with internal cues of true hunger. It is at this age—when midmorning school snacks disappear and school lunch scheduling has more to do with numbers of students than with actual lunchtime appetites—that after-school hunger may intensify. This is the time to provide healthful snacks or at least stock the kitchen shelves with an assortment of nutrient-dense treats (see Box 12-1). If children purchase snacks away from home, adults can develop guidelines with children this age to maintain positive eating styles. The intent is to supplement the nutrients received during meals with nutrient-dense snacks so the total caloric and nutrient intake is adequate to meet the needs of growth at each childhood stage. Snacking, though, seems to have changed in definition and frequency. A recent study of 31,337 children and adolescents assessed snacking and meal intake trends from 1977 to 2006. On average the number of calories and eating events (a total of snacks and meals) increased substantially over time. Compared to the 1970s, about half of American children average 4 snacks a day, while others consume snacks and meals as many as 10 times a day or basically nonstop eating. This means that an excessive number of calories, most likely less-nutrient-dense snack foods, are being consumed and the consumption of nutrient-dense meal time foods are decreasing. While the increase of snack calories is only 168 kcal, this number represents an average, signaling that for many children the excess intake is higher. With increased eating episodes, there can be a concern that eating is not due to physiological hunger but to a habit from needing a constant state of satiation.7 Mineral needs increase as well. Because of increased bone growth and mineralization, calcium Adequate Intake (AI) recommendations jump from 800 mg/day at age 8 to 1300 mg/day throughout adolescence. Iron and zinc allowances increase as well. Well-chosen dietary intakes will provide sufficient amounts of these nutrients. Marginal intakes of zinc have been noted among schoolchildren that are finicky eaters; low zinc intakes can affect growth rates.8 The growth cycle of this age span is important for both parents and children to understand. Attention to issues related to weight, appropriate appetite, and meal patterning is crucial for positive eating relationships and may prevent the development of eating disorders. By understanding the relationship of nutrients and kcal to their growth needs, children possess sufficient information to take responsibility for certain aspects of their food choices and dietary patterns. Children with special needs who are challenged by physical and/or mental limitations may require additional support to achieve nutritional adequacy (Box 12-2). Ultimately, however, adults must provide nourishment for children and guidance as to positive health behaviors. Several techniques can be used with children this age. MyPyramid for Kids is similar to the adult version but presents games and other creative approaches for children to visualize and understand the serving sizes and types of foods that result in a balanced nutrient intake. These can be found at www.mypyramid.gov (Figure 12-3). Another source for appropriate techniques is the “Fruits & Veggies, More Matters” site. Resources for parents and children are available at www.fruitsandveggiesmorematters.org. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) was established to protect the health and wellness of American children. Formalized in 1946, the program provides lunches at varying costs, depending on family income, to all schoolchildren at public and nonprofit private schools and residential child care institutions. At the federal level the program is administered by the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), at the state level by various agencies, and locally by school boards. As an entitlement program, the NSLP provides funds to all schools that apply and meet the criteria of eligibility. Currently, about 95% of all school districts participate in this program. Every school district is required to implement a local school wellness policy to focus on obesity prevention and through modification of school environments support healthy eating habits and physical activity.9 At participating schools, there are two types of eligibility to qualify for free or reduced price meals; both usually require family to complete and return application forms. Categorical eligibility is based on the child’s household receiving food stamps from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) or participating in the Food District Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), and free meals for the homeless, runaways, and children of migrant workers. Income-based eligibility offers reduced-price meals to children whose household income is below 185% of the federal poverty level; free meals are available to those falling below 130% of the poverty level. Through the process of direct certification, school districts qualify children without requiring submission of family applications. School districts work with state or local SNAP, TANF, and FDPIR agencies to certify children in households. During the 2008-2009 school year, NSLP served meals daily to 31.2 million children. About 60% of these children received free or reduced-price lunches.9 Basically, lunch must provide approximately one-third or more of the recommended levels for key nutrients, providing no more than 30% kcal from fat and less than 10% of kcal from saturated fat. For low-income children participating in the program, this provides one-third to one-half of their daily intake.9 The School Breakfast Program was created in 1966 to support schools by providing morning meals in areas where children ride buses to school and/or most mothers are in the work force, particularly in economically disadvantaged areas. The program has reduced tardiness and decreased absenteeism. It is administered through the same governmental offices as the School Lunch Program and is also an entitlement program. During the 2008-2009 school year, more than 86,000 schools and institutions participated in the School Breakfast Program, serving 10.8 million children. More than 81% of the participants qualify for free or reduced-priced meals. More than 47% of the children from low-income families receive both school lunch and school breakfast.9 During summer, the Summer Food Service Program for Children (SFSP) functions through a range of eligible organizations including schools, summer camps, and community agencies, as well as various federal, state, and local government departments. The purpose is to serve meals to school-age children when schools are not in session in communities where children depend on school meals as an essential component of their daily nourishment.9 When fast foods become the mainstay of an individual’s diet, regardless of age, some nutrients such as vitamin A and C may be lacking and overconsumption of dietary fats and kcal may occur. Although teens may be seen at such restaurants, most other customers consist of families with young children as well as older adults. Fast foods affect the nutrient intake of all ages (see the Teaching Tool box, Fast-Food Choices).

Life Span Health Promotion

Childhood and Adolescence

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Life Span Health Promotion

Stages of Development

Childhood (1 to 12 Years)

Stage I: Children 1 to 3 Years Old

Nutrition requirements

Stage II: Children 4 to 6 Years Old

Stage III: Children 7 to 12 Years Old

Nutrition requirements

Childhood Health Promotion (1 to 12 Years)

Knowledge

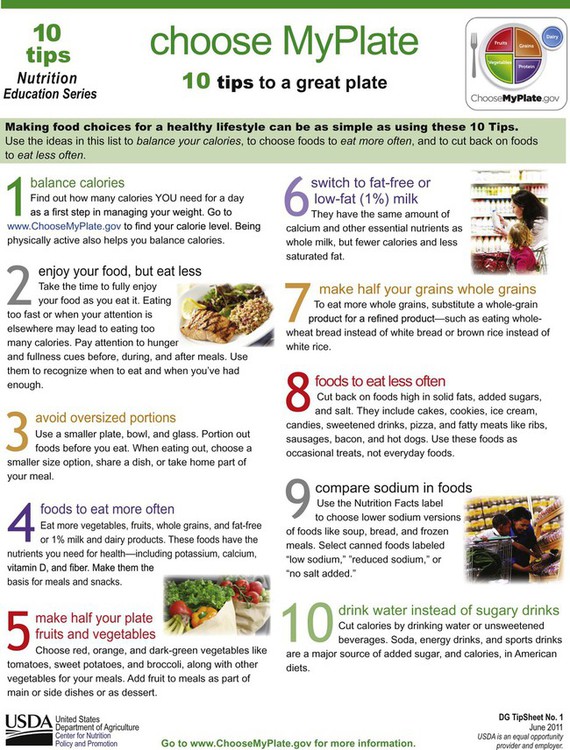

Techniques

Community Supports

School food service

Adolescence (13 to 19 Years)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Life Span Health Promotion: Childhood and Adolescence

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access