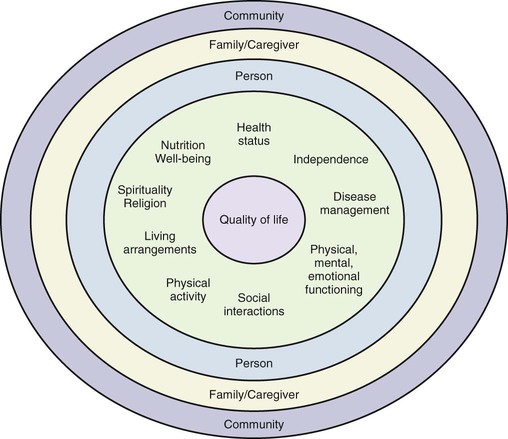

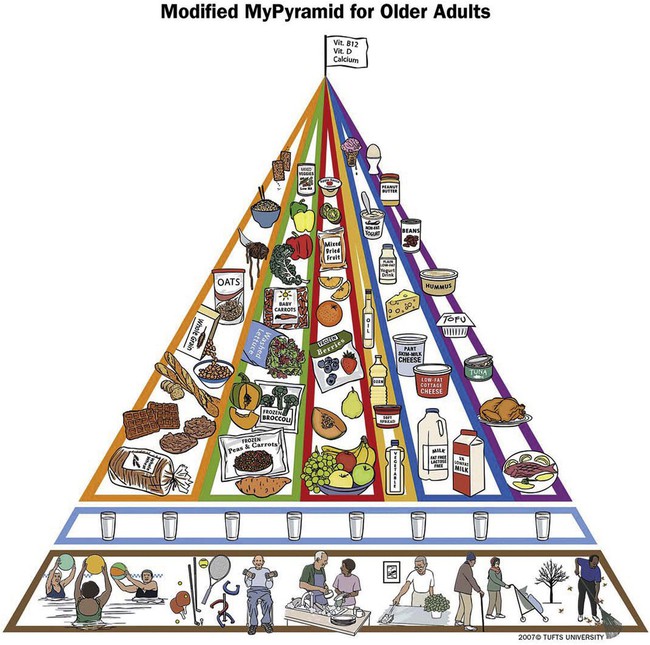

Aging is a gradual process that reflects the influence of genetics, lifestyle, and environment over the course of the life span. The purpose of cell creation begins changing around age 30. No longer supplying new cells for growth and development, cell metabolism slows down and instead creates new cells to replace old cells. At older ages, this process of cell replication slows even more, and the effects of aging on body organs begin to appear. Some body systems are more affected than others, and the changes may begin to affect nutritional status. Other organ functions that may be altered include taste and smell, saliva secretions, swallowing difficulties, liver function, and intestinal function. For example, the gastrointestinal tract functions are diminished by reduced production of gastric juices such as hydrochloric acid, which results in decreased absorption of nutrients. The systems and the effects of aging are listed in Table 13-1. TABLE 13-1 Data from Rosenberg IH, Russell RM, Bowman BB: Aging and the digestive system. In Munro HN, Danford E, editors: Nutrition, aging, and the elderly, New York, 1989, Plenum Press. The concept of productive aging considers the many psychosocial influences on successful aging. Productive aging refers to an overall process of aging that is dependent on attitudes and skills developed over the course of one’s life. These attitudes and skills prepare an individual to adapt to the transitions of life and maintain a personal sense of experiencing a productive, meaningful life.1 Successful aging considers that different criteria of success apply during the older years compared with those of the earlier life span categories. Box 13-1 is a list of 15 ways to promote successful aging that was developed from suggestions by older adults.1 These years mark a transition from one stage of the life span to another; young adults separate from their family of origin, focus on personal and career goals, and often face reproductive decisions (Figure 13-1). As such, it is a prime time to either refine or establish an eating style that promotes health, possibly preventing future development of diet-related diseases. National surveys, though, continue to report that few adults consume the health-promoting recommended intakes of fruits and vegetables. As of 2007, 76% of American adults reported consuming fewer than 5 servings of fruits and vegetables a day.2 A self-review or assessment by a nutrition professional can assist in creating a personal schedule that allows time for planning and preparation of simple yet high-quality meals. Many women bear children during these years. The nutrition and health requirements of pregnancy are detailed in Chapter 11. Layered on these needs during this life span stage are often employment and other family commitments, all of which affect nutritional and health behaviors. Physically caring for young children, although eminently rewarding, may be exhausting. Throughout the mother’s pregnancy and during childbearing, the father’s role in terms of health issues is often ignored. Although the woman’s body is nourishing fetal development, the father is under stress as he prepares to support additional responsibilities. Fathers also need to be at optimum health, especially during the first few years of childrearing when physical stamina is put to the test. The RDA for protein increases for women from 46 to 50 g and for men from 58 to 63 g daily; these ranges reflect lean body mass growth that may occur in both men and women through about age 24. Vitamin and mineral needs do not significantly change. Calcium and phosphorus needs for men and women decline after age 18 because skeletal growth is almost complete. Daily Adequate Intake (AI) recommended calcium levels up to age 18 are 1300 mg, dropping to 1000 mg from 19 years on. For phosphorus, RDA levels up to age 18 are 1250 mg a day, dropping to 700 mg from 19 years on. Maintaining calcium and iron intake continues to be a concern for women because of their often-restricted intake of food during dieting. (See also Box 7-1 or Box 8-3 regarding nutrients and their functions.) The years from 40 to 50 are marked by a continuation of family demands and career involvement. Some middle-year adults may be faced with caring for aging parents (Figure 13-2); this increased stress and responsibility may be offset by the seemingly reduced parenting of their own children. As older children leave for college or move into their own residences, the resultant “empty nest” necessitates rediscovering preparation of dinners for two or, for single parents, dinners for one. With family meals no longer a requirement, many middle-year adults often have the finances and time for restaurant dining. However, making the transition to food preparation styles and dietary patterns that maintain healthful dietary patterns is crucial. During the middle years, cell loss rather than replication occurs. Kcal needs decline as lean body mass is lost and replaced by body fat that is less metabolically active. Women in particular experience an increase in body fat composition. Body fat increases can be slowed by exercise and strength training to continue maintenance of lean body mass. After age 50, daily energy needs drop from 2200 to 1920 kcal for women and from 2900 to 2300 kcal for men. It is a challenge to meet the same nutrient needs with reduced kcal intake. Protein needs remain constant for both genders. Iron requirements for women drop from 18 to 8 mg, which reflects reduced iron loss because of menopause. (See also Box 7-1 or Box 8-3 regarding nutrients and their functions.) Overall, quality of life for older adults depends on factors that influence daily experiences. These factors include health status; nutrition well-being; spirituality; living arrangements; physical activity; social interactions; physical, mental, and emotional functioning; disease management; and level of independence (Figure 13-3). The level of wellness experienced during this stage of life often reflects the quality of life resulting from health behaviors through the several life span stages. A lifetime of physical fitness and good nutrition allows an individual to enter these years with more stamina, cardiovascular conditioning, and solid health-promoting habits that enable him or her to overcome the inevitable slowing down or physical limitation of the later years (Figure 13-4). Even those who were not always active have been shown to benefit from regular exercise. Strength training has improved the muscle tone and stamina of older men and women.3 Disorientation or senility often associated with aging may be caused by improper use of medications, marginal nutrient deficiencies (e.g., vitamin B12), or simple dehydration. Older clients may intentionally restrict fluids because of incontinence, nocturia (excessive urination at night), or the inability to get to the toilet on their own. Some older adults lose their sense of thirst and forget to consume enough fluids. Fluid requirements in older adults remain the same as in younger adults (about 8 cups daily is sufficient) unless a medical condition or medication prescribes otherwise. The signs of dehydration are listed in Box 13-2. Medical diagnosis should be sought to determine the specific etiology of these signs. Nutrition status may be affected by restricted access to food and ability to prepare meals. Shopping may be difficult without transportation, and mobility to walk through stores may be limited. Funds for food may be constrained, and often food quantities available are beyond the amounts that can be used by individuals living alone. Once foods are purchased, preparation may be affected by physical limitations caused by progressive chronic illnesses such as arthritis. Some older adults may no longer have an interest in cooking. Others have become so frightened about foods containing too much fat or cholesterol that they become malnourished. For individuals in this age bracket, there is not sufficient evidence to warrant restrictive dietary intake; in actuality, malnutrition and underweight are more detrimental than excess dietary fat and cholesterol intake. Box 13-3 lists risks factors for malnutrition of older adults. Dietary management for older adults may be more complicated than for other stages of adulthood. For example, obesity is viewed as a form of malnutrition of an older adult.4 For younger adults, reducing body mass index (BMI) decreases health risks. For older adults, decreased BMI may be associated with increased risk of strokes. Having an average BMI provides healthful weight reserves during times of illness.4 Studies of weight reduction strategies seldom include older participants, so their complex physiologic, behavioral, and social needs are not considered. Additionally such strategies may overly limit intake of essential nutrients, further increasing malnutrition.4 Another aspect of older adult dietary management is protein adequacy. Total body protein decreases as aging progresses. Although the loss of skeletal muscle is the most noticeable body protein lost, organ tissue, blood components, and immune bodies are also affected, including compromised wound healing, loss of skin elasticity, reduced ability to battle infection, and longer recuperation from illness and surgeries.5 Dietary intake may be further altered when these physical factors combine with social factors, leading to reduced protein intake. Consumption of micronutrients found in protein foods also may be limited, leading to deficiencies of B12, A, C, D, calcium, iron, zinc, and others.6 This need, combined with the greater turnover of whole-body protein of aging bodies, results in older adults needing greater dietary protein intake (1 g/kg body weight) compared with younger adults (0.8 g/kg body weight).5 Frail elderly women are most at risk for these micronutrient deficiencies. Living arrangements also affect nutritional status. A variety of living arrangements exists for older adults. Although many continue to live in their own homes or with family members, some opt for retirement communities, and others, because of health conditions, may reside in long-term care facilities or nursing homes. Living in one’s own home provides the freedom to prepare and eat foods whenever desired; illness, however, may make shopping for food and preparing it difficult. Retirement communities may provide transportation to food stores and more social events involving meals (Figure 13-5), although residents still are responsible for their own food preparation. Long-term care facilities usually provide prepared meals, but the style of cooking may not be as appealing or comforting as home-prepared meals. A challenge for meeting the nutritional needs of institutionalized older adults is that the DRIs used to guide nutrient levels are intended to meet the needs of healthy older adults. Adjustments are necessary for individual circumstances of acute or chronic illness to achieve rehabilitation, recuperation, or maintenance to reduce the risk of further complications.7 Consequently, it is now recommended that diets in long-term care facilities be liberalized to improve dietary intake of this age group.8 The DRIs remain constant from age 51 years and older for men and women, except for vitamin D. What does change is the ability of the body to either process or synthesizes certain nutrients. Synthesis of vitamin D is reduced; the AI for vitamin D for individuals older than age 70 increases to 15 mcg a day compared with 10 mcg a day for ages 51 to 70 years. Older adults either need more exposure to sunlight to produce required amounts of vitamin D or require a supplement if so diagnosed by a physician, qualified nutritionist, or dietitian. Because of decreased production of gastric juices and intestinal enzymes, digestion and absorption may be reduced, further highlighting the need for optimum nutrient intake. The production of the intrinsic factor required for vitamin B12 absorption also may be reduced, increasing the risk of pernicious anemia. New recommendations suggest the use of vitamin B12 supplements or consumption of foods fortified with vitamin B12 to meet the RDA of 2.4 mcg/day (see also Box 7-1 or Box 8-3 regarding functions of nutrients). Overconsumption of simple sugars and sodium may exacerbate other diet-related disorders such as diabetes and hypertension. As the muscularity of the digestive system weakens, constipation may be a problem, especially after a lifetime of low-fiber foods. Constipation may be alleviated by slowly increasing consumption of whole-wheat products, fruits, vegetables, and fluids, as well as increasing exercise. The Modified MyPyramid for Older Adults, developed by Tufts University, highlights nutrient-dense foods and fluid intake while also suggesting different forms of foods that may be more easily available (Figure 13-6).

Life Span Health Promotion

Adulthood

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Aging and Nutrition

EFFECT ON NUTRITIONAL STATUS

CAUSED BY

ORGAN INVOLVED

↓Ability to taste salt and sweets

↓Taste buds

Tongue and nose

↓Palatability of food

↓Taste and olfactory nerve endings

↓Food intake

↓Taste and smell

Reduced sense of thirst/dry mouth

↓Saliva production

Salivary glands

Difficulty chewing

Minor effects on swallowing (but may progress to dysphagia)

Muscle contractions may malfunction

Esophagus (and swallowing process)

↓Bioavailability of vitamins, minerals, proteins

↓Hydrochloric acid (HCl) secretion and intrinsic factor

Stomach

↓Absorption of vitamin B12 and folate

↓Pepsin

Stomach

↓Drug doses (adjustments possible to prevent overdosing)

↓Production of drug-metabolizing enzymes

Liver

Productive Aging

Stages of Adulthood

The Early Years (20s and 30s)

Nutrition Requirements

The Middle Years (40s and 50s)

Nutrition Requirements

The Older Years (60s, 70s, and 80s)

Physical Activity

Physical, Mental, and Emotional Functioning

Nutrition Well-Being

Living Arrangements

Nutrition Requirements

Life Span Health Promotion: Adulthood

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access