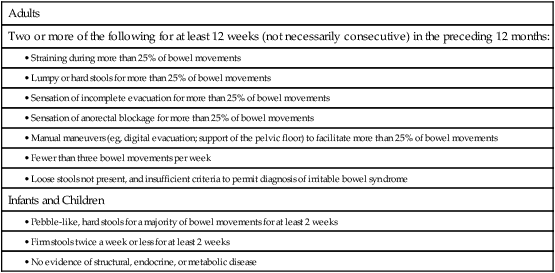

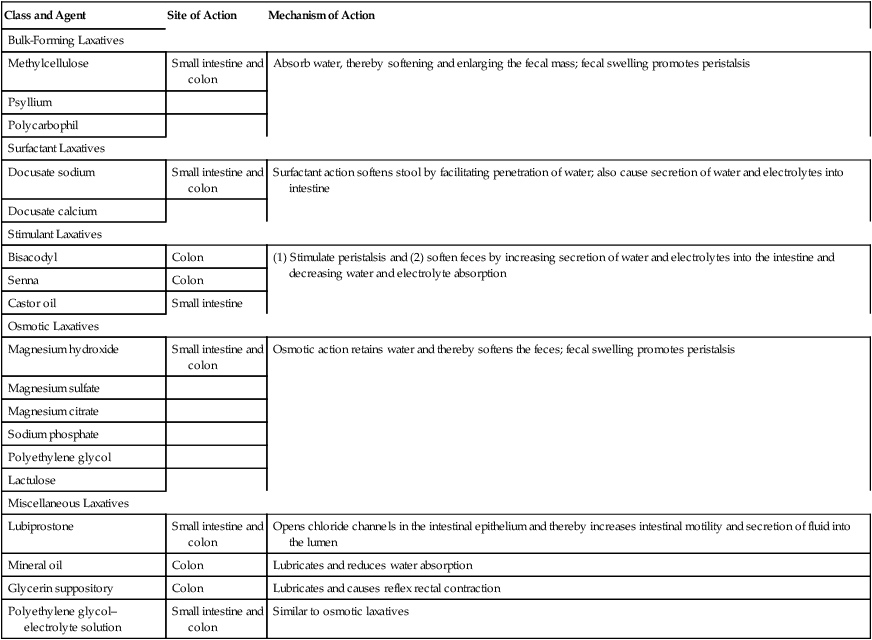

CHAPTER 79 Constipation is defined in terms of symptoms, which include hard stools, infrequent stools, excessive straining, prolonged effort, a sense of incomplete evacuation, and unsuccessful defecation. Scientists who do research on constipation usually define it using the Rome II criteria (Table 79–1). As Table 79–1 shows, constipation is determined more by stool consistency (degree of hardness) than by how often bowel movements occur. Hence, if the interval between bowel movements becomes prolonged, but the stool remains soft and hydrated, a diagnosis of constipation would be improper. Conversely, if bowel movements occur with regularity, but the feces are hard and dry, constipation can be diagnosed—despite the regular and frequent passage of stool. TABLE 79–1 Rome II Criteria for Constipation Traditionally, laxatives have been classified according to general mechanism of action. This scheme has four major categories: (1) bulk-forming laxatives, (2) surfactant laxatives, (3) stimulant laxatives, and (4) osmotic laxatives. Representative drugs are listed in Table 79–2. TABLE 79–2 Classification of Laxatives by Pharmacologic Category From a clinical perspective, it can be useful to classify laxatives according to therapeutic effect (time of onset and impact on stool consistency). When these properties are considered, most laxatives fall into one of three groups, labeled I, II, and III in this chapter. Group I agents act rapidly (within 2 to 6 hours) and give a watery consistency to the stool. Laxatives in group I are especially useful when preparing the bowel for diagnostic procedures or surgery. Group II agents have an intermediate latency (6 to 12 hours) and produce a stool that is semifluid. Group II agents are the ones most frequently abused by the general public. Group III laxatives act slowly (in 1 to 3 days) to produce a soft but formed stool. Uses for this group include treating chronic constipation and preventing straining at stool. Representative members of groups I, II, and III are listed in Table 79–3. TABLE 79–3 Classification of Laxatives by Therapeutic Response

Laxatives

General considerations

Constipation

Adults

Two or more of the following for at least 12 weeks (not necessarily consecutive) in the preceding 12 months:

Infants and Children

Laxative classification schemes

Class and Agent

Site of Action

Mechanism of Action

Bulk-Forming Laxatives

Methylcellulose

Small intestine and colon

Absorb water, thereby softening and enlarging the fecal mass; fecal swelling promotes peristalsis

Psyllium

Polycarbophil

Surfactant Laxatives

Docusate sodium

Small intestine and colon

Surfactant action softens stool by facilitating penetration of water; also cause secretion of water and electrolytes into intestine

Docusate calcium

Stimulant Laxatives

Bisacodyl

Colon

(1) Stimulate peristalsis and (2) soften feces by increasing secretion of water and electrolytes into the intestine and decreasing water and electrolyte absorption

Senna

Colon

Castor oil

Small intestine

Osmotic Laxatives

Magnesium hydroxide

Small intestine and colon

Osmotic action retains water and thereby softens the feces; fecal swelling promotes peristalsis

Magnesium sulfate

Magnesium citrate

Sodium phosphate

Polyethylene glycol

Lactulose

Miscellaneous Laxatives

Lubiprostone

Small intestine and colon

Opens chloride channels in the intestinal epithelium and thereby increases intestinal motility and secretion of fluid into the lumen

Mineral oil

Colon

Lubricates and reduces water absorption

Glycerin suppository

Colon

Lubricates and causes reflex rectal contraction

Polyethylene glycol–electrolyte solution

Small intestine and colon

Similar to osmotic laxatives

Group I: Produce Watery Stool in 2–6 Hr

Group II: Produce Semifluid Stool in 6–12 Hr

Group III: Produce Soft Stool in 1–3 Days

Osmotic Laxatives (in High Doses)

Magnesium salts

Sodium salts

Polyethylene glycol

Others

Castor oil

Polyethylene glycol–electrolyte solution

Osmotic Laxatives (in Low Doses)

Magnesium salts

Sodium salts

Polyethylene glycol

Stimulant Laxatives (Except Castor Oil)

Bisacodyl, oral*

Senna

Bulk-Forming Laxatives

Methylcellulose

Psyllium

Polycarbophil

Surfactant Laxatives

Docusate sodium

Docusate calcium

Others

Lactulose

Lubiprostone

Laxatives

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access