Chapter 38 Pain, labour and women’s choice of pain relief

After reading this chapter, you will:

An exploration of pain in labour

Pain is complex, personal, subjective, and a multifactorial phenomenon influenced by psychological, physiological and sociocultural factors. Though pain is universally experienced and acknowledged, it is not completely understood (Lowe 2002). Pain is usually associated with injury and tissue damage, thus a warning to rest and protect the area. However, in childbirth, pain is considered to be a side-effect of the process of a normal event (Simkin & Bolding 2004). Increasing pain at the end of pregnancy is often the first sign that labour has commenced (McDonald 2006).

The origins of labour pain are centred on the physiological changes which take place during labour. Pain predominates from the cervix and lower uterine segment, particularly in the first stage of labour (McDonald 2001). Effacement and dilatation of the cervix causes the stripping of membranes away from the uterine lining, hence the ‘show’ of early labour (McDonald 2006). This causes prostaglandin release. (See Chs 35 and 36.)

Prostaglandin aids the contractility of the myometrium, playing an important role in the initiation of labour (RPSGB & BMA 2008). Manipulation of the cervix during a vaginal examination directly stimulates the production of prostaglandins and increases pain. Nerve endings are stimulated, resulting in a form of inflammatory response in the tissues, which creates pain signals. This response produces histamine, serotonin and bradykinins, which stimulate the nociceptors in the cervix, setting up pain sequences. This stimulates an action potential in the nerve, setting up a chain reaction to the spinal cord and the higher centres in the brain (Tortora & Grabowski 2000, Yerby 2000).

Uterine nerve supply and nerve transmission

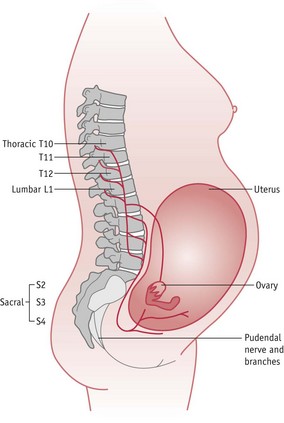

The autonomic nervous system serves the uterus with sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibres (see Ch. 35). Nerve pathways supplying the uterus and cervix arise from afferent fibres of the sympathetic ganglia. Nerve endings in the uterus and cervix pass through the cervical and uterine plexuses to the pelvic plexus, the middle hypogastric plexus, the superior hypogastric plexus and then to the lumbar sympathetic nerves to eventually join the thoracic 10, 11, 12 and lumbar 1 spinal nerves (Fig. 38.1).

Figure 38.1 Pain pathways.

(Reprinted from Pain in childbearing, Yerby M (ed), 2000, by permission of the publisher Baillière Tindall.)

The nerve supply to the perineum and lower pelvis from the second and third sacral nerve roots meets the plexuses from the uterus at the Lee–Frankenhäuser plexus at the uterovaginal junction (Stjernquist & Sjöberg 1994) (see Ch. 25). These nerves transmit pain in the second stage of labour.

Nerve transmission is along fibres that conduct sensations in different strengths and at different speeds. These fibres are either A delta, thinly myelinated fibres, or C fibres, which are unmyelinated. It is the smaller C fibres which are found in the deep viscera, such as the uterus, that give rise to the deep prolonged pain of labour when stimulated by muscular contraction and chemical substances (McDonald 2006, McGann 2007).

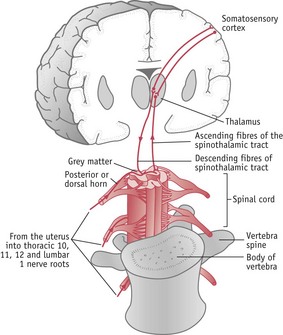

Pain sensation is transferred by action potentials (see website) along the nerve fibres to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, thence via upward tracts to the central nervous system (McCool et al 2004) (Fig. 38.2). Because of the release of bradykinins and histamines and other pain-inducing substances at tissue level, ‘substance P’ is also released. This is a neuropeptide and is released from the afferent nerves (McGann 2007) as part of the ‘signalling process’ of pain on its way to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord; it could be termed a potentiator of pain sensation.

Figure 38.2 Brain and spinal cord connections.

(Reprinted from Pain in childbearing, Yerby M (ed), 2000, by permission of the publisher Baillière Tindall.)

As the action potentials from the afferent neurons meet the spinal cord they enter by the posterior (dorsal) root and are transferred to the substantia gelatinosa at laminae (or layers) II and III of the grey matter of the spinal cord. These laminae decode various types of stimulus and transfer sensations to the higher centres of the brain via the anterior and lateral spinothalamic tracts, which cross to the opposite side of the cord before ascending, and are perceived as pain by the cerebral cortex (McCool et al 2004).

Descending tracts from the brain, returning to the spinal cord, may have a modulating effect on the nerve transmission of pain (Fig. 38.2). Naturally occurring endorphins at the spinal level act like exogenous opioids by modulating pain response (McGann 2007, Millan 2002).

As labour progresses, signs of the effect of pain on the woman become evident. Pain causes a boost in catecholamine secretion, thus increasing levels of adrenaline. The result is a rise in cardiac output, heart rate, and blood pressure, possibly causing hyperventilation that decreases cerebral and uterine blood flow by vasoconstriction, which may affect contractility of the uterus (McDonald 2006). Uterine contractions may be lessened by increased levels of adrenaline and cortisol and can cause uncoordinated uterine activity (McDonald & Noback 2003). Hyperventilation tends to alter oxygen balance, which may modify the acid–base status of the blood, causing maternal alkalosis, which may in turn cause fetal hypoxia (Lowe 2002).

Pain gate theory

Melzack & Wall (1965) described a mechanism for modulating pain at spinal cord level. Opioid-like substances, namely endorphins and enkephalins, are neurotransmitters and neuromodulators. These are found principally in the sensory pathways where pain is relayed (Melzack & Wall 1965). With greater understanding of endorphins and their opiate-type properties, it was noted that they dampened the effect of substance P. They are highly effective pain-modulating substances that play a role in pleasure, learning and memory (McGann 2007).

Psychological aspect of pain

Whilst it may be easy to acknowledge physical pain, the pain in labour has a psychological component. This is a point to be appreciated by midwives and other health professionals. The psychological influences were recognized in the early theories of nociception (Eccleston 2001), which claimed that the manner in which individuals perceive and respond to pain involves more than peripheral input (Adams & Field 2001).

There exists an affective dimension of pain, which relates not only to the unpleasant feelings of discomfort but also to emotions that may be connected to memories or imagination (Price 2000a). Anxiety related to pain has a protective role that facilitates appropriate behaviours (Carleton & Asmundson 2009) which may be necessary to prepare for the impending birth. However, individuals with high levels of anxiety sensitivity tend to become fearful of the symptoms of pain, demonstrating states of hypervigilance (Thompson et al 2008). This fear may relate to the pain that is currently present but also to perceptions and concerns of what could occur (Carleton & Asmundson 2009). Individuals choose to avoid what they consider to be potentially pain-inducing situations as a result of this fear (Hirsh et al 2008). As such, this may result in what Hirsh et al (2008) describe as pain catastrophizing in reaction to childbirth – a predisposition to underestimate a personal ability to deal with pain, while exaggerating the threat of the pain anticipated. Catastrophizing has been shown to be positively associated with avoidance behaviour in labour (Flink et al 2009).

It should be noted that perceptions of pain will vary among women even when the stimuli are similar. Women react to their labour pains in different ways. This may result in a range of behaviour, such as distraction (Eccleston 2001) or feelings of anger and entrapment (Morley 2008). Maternity caregivers will need to be alert to women’s expectations when dealing with their individual pain. It is important to provide clear and brief communication, repeat and explain points where necessary, and make an effort to provide consistent information and guidance (Eccleston 2001).

Cultural aspect of pain

Midwives should acknowledge that the definition, understanding and manifestation of pain will be influenced by cultural experiences of both the woman and her caregivers. Culture affects attitudes toward pain in childbirth, how women cope with this and how they manage it (Callister et al 2003). While some individuals may accept intervention when in pain, others may demonstrate a more stoic approach and avoid help because of their socialization towards behaviour in such circumstances (Davidhizar & Giger 2004).

Various qualitative studies have shown how women from different backgrounds perceive and deal with the pain associated with childbirth. In their research, Johnson et al (2004) found that Dutch women felt that birth was a normal phenomenon that is accompanied by pain, which, though difficult, should not be feared, but used effectively. Somalian women in the study by Finnström & Söderhamn (2006) had been told that it was not acceptable to cry and wail when in pain. As an alternative, they felt that it was necessary to stay in control, tolerate the pain and involve a friend or a family member to help them cope with the event. In Jordan, Abushaikha (2007) found that women utilized spiritual methods to cope and were required to demonstrate patience and endurance towards the pain as a show of strong faith. The women in this study had to ensure that they were not overheard and were expected to labour silently.

Midwives’ own cultural experiences of pain will affect their interpretation and attention to women in labour. A study in Scotland comparing Chinese with Scottish women, indicated through one midwifery manager’s comment, that a loud coping strategy was occasionally misconstrued by health workers. They were more likely to interpret this as a sign of inability to cope and offer the women analgesia or anaesthetics. Those who remained quiet were often unnoticed (Cheung 2002).

There is a need for cultural competence when caring for women in childbirth (Brathwaite & Williams 2004). Midwives must develop their ability to interpret and understand the verbal communication of pain, and also body language, in order to address the needs of individuals from culturally diverse groups (Finnström & Söderhamn 2006). Awareness of the cultural meanings of childbirth pain, how different women cope and are expected to behave, will assist in the provision of culturally competent care (Callister et al 2003). Cultural assumptions made by midwives, as any assumptions, may prevent individualized and appropriate care.

Impact of the environment on childbirth pains

Crafter (2000) postulated that the place of birth may have a significant impact on women’s experiences of pain in labour and birth because part of a culture is expressed through its environment and organization. The Peel Report (DHSS 1970) promoted changes in the place of birth for women, who had traditionally given birth to their babies at home. Hospitalization altered women’s views of birth, leading to a more medicalized birth with greater use of drugs for pain relief, which many women now accept as a normal part of the new environment. Crafter (2000) suggests that furnishings within a room may give women subliminal messages about the presiding culture. For example, an environment simulating the home may indicate behaviour of being in a home, whilst a hospital environment may promote behaviour for that environment.

Preparation for pain in childbirth

The potential value of antenatal education and preparation in reducing the fear and anxiety associated with childbirth was recognized by Grantly Dick-Read (1944) and Lamaze (1958). They proposed that labour was not inherently painful. Dick-Read (1944), who appears to be the original authority in this area, endorsed the view that pain was influenced by women’s socio-culturally conditioned fear and expectation of birth. They both suggested that labour pains could be controlled by psychoprophylactic techniques, such as muscle relaxation and breathing exercises. Dick-Read (1944) also postulated that providing information and encouraging women to communicate was useful in preparing women for pain in childbirth. The main goal of antenatal classes, which adopt these techniques, is based on empowering women to identify and develop their own body resources to enhance their childbirth experience (Gagnon & Sandall 2007).

The literature regarding the effectiveness of childbirth education is inconclusive (Koehn 2002). According to Spiby et al (2003), antenatal classes have been associated with increased ability to cope, lower levels of the affective aspect of pain and less use of pharmacological pain relief in labour. However, Lothian (2003) found that only 15% of the women in her study identified childbirth education classes as their source of information about pain relief, with most women depending on their midwives or doctor for explanations. With increasing technology, women may also easily access information through other sources, including the Internet. The Cochrane review by Gagon & Sandall (2007) recognized that the benefits of antenatal education for childbirth remain ambiguous though highlighted that the main body of literature suggests that some expectant parents want antenatal classes, particularly with their first baby.

The content of antenatal classes related to pain management during labour needs to be developed. Antenatal course leaders should prepare women for their subjective experience of pain in labour (Schott 2003) by helping them to explore their own needs, attitudes and expectations of labour (Schneider 2001). Often women are not able to make choices about the management of their pain in labour because they are ignorant of their own body’s resources for coping with pain (Nolan 2000). Women will need brief information on the relevant physiology of pain (Robertson 2000) and be presented with a realistic but positive approach to pain in labour (Schott 2003).

During antenatal classes, women should be helped to explore and articulate the range of coping strategies they have used in their own previous experiences of pain, so the positive methods can be enhanced and negative strategies can be replaced with an alternative (Escott et al 2004). It is not unheard of that in labour, when in a mood of panic and acute anxiety, women claim to have forgotten how to ‘breathe’. Antenatally, if they have been encouraged to recall and develop their own pre-existing methods of tolerating pain, it may be easier for them to develop a greater sense of self-efficacy to deal with their labour pains (Escott et al 2005).

Concept of support in labour

Women need to feel supported during labour. This may take the form of informational, practical or emotional support (Hodnett et al 2007) which are all essential elements in the art of midwifery (Berg & Terstad 2006). Support in labour impacts on the sympathetic element of the autonomic nervous system, by breaking the fear–tension–pain cycle observed by Dick-Read (Mander 2000).

A correlation study in the US by Abushaikha & Sheil (2006) examined the relationship between the feeling of stress and support in labour. The findings suggested that women with greater support reported less stress compared to those who received little.

The main sources of support for some mothers are the midwife and the woman’s partner. However, these sources are reliant on the society and culture to which the woman belongs. The findings of a literature review suggested that support for women varies in different countries. This support includes untrained lay women, female relatives, nurses, monitrices (midwives who were self-employed birth attendants) and doulas (Rosen 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree