On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Differentiate between preterm birth and low birth weight. • Discuss major risk factors associated with preterm labor. • Analyze current interventions to prevent spontaneous preterm birth. • Discuss the use of tocolytics and antenatal glucocorticoids in preterm labor. • Evaluate the effects of prescribed bed rest on pregnant women and their families. • Design a nursing care plan for women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes (preterm PROM). • Describe the care of a woman with postterm pregnancy. • Explain the challenge of caring for obese women during labor and birth. • Summarize the nursing care for a woman experiencing a trial of labor, induction or augmentation of labor, a forceps- or vacuum-assisted birth, a cesarean birth, or a vaginal birth after a cesarean birth (VBAC). • Discuss obstetric emergencies and their appropriate management. Preterm labor is defined as cervical changes and uterine contractions occurring between 20 and 37 weeks of pregnancy. Preterm birth is any birth that occurs before the completion of 37 weeks of pregnancy, regardless of birth weight. Complications related to preterm birth account for more newborn and infant deaths than any other cause (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). In 2010 the preterm birthrate for all races in the United States dropped for the fourth year in a row, to 11.99% (Martin, Hamilton, Sutton, et al., 2012). This decline was largely the result of three major practice changes: (1) improved fertility practices that reduced the risk for higher-order multiple gestations; (2) limiting scheduled births at less than 39 weeks of gestation to only those with valid indications; and (3) increased use of strategies to prevent recurrent preterm birth (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). The World Health Organization estimates that 9.6% (almost 13 million) of all births worldwide in 2005 were preterm. The rate of preterm birth is highest in Africa and North America and lowest in Europe. In the United States, African-American women have the highest rates of preterm birth, almost twice as high as those of other racial and ethnic groups. This is particularly apparent for births that occur at less than 32 weeks of gestation (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). About 75% of all preterm births in the United States are termed late preterm because they occur between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation. Late preterm infants are at increased risk for early death and long-term health problems when compared with infants who are born full term. Although late preterm babies do experience significant problems, the great majority of infant deaths and the most serious morbidity occur among the 16% of all preterm infants who are born before 32 weeks of gestation (very preterm birth) (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). Although they have distinctly different meanings, the terms preterm birth or prematurity and low birth weight are often interchanged. Preterm birth describes length of gestation (i.e., less than 37 weeks regardless of the weight of the infant), whereas low birth weight describes only weight at the time of birth (i.e., 2500 g or less). Because birth weight was far easier to determine than gestational age, in many settings and publications low birth weight was used as a substitute term for preterm birth. Preterm birth, however, is a more dangerous health condition for an infant because less time in the uterus correlates with immaturity of body systems. Low-birth-weight babies can be, but are not necessarily, preterm. Low birth weight can be caused by conditions other than preterm birth, such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), a condition of inadequate fetal growth not necessarily correlated with initiation of labor. Pregnant women who have various complications of pregnancy that interfere with uteroplacental perfusion, such as gestational hypertension or poor nutrition, may give birth to a baby at term who is low birth weight because of IUGR. However, infants born at a preterm gestation can weigh more than 2500 g at birth, such as infants born to women with diabetes who have poorly controlled blood glucose levels. Today, thanks to advances in pregnancy dating, outcomes related to gestational age can increasingly be distinguished from outcomes related to birth weight (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). Preterm birth is divided into two categories: spontaneous and indicated. Spontaneous preterm birth occurs after an early initiation of the labor process and comprises nearly 75% of all preterm births in the United States. Conditions such as preterm labor with intact membranes, preterm premature rupture of membranes (preterm PROM), cervical insufficiency, or amnionitis often result in preterm birth (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). Indicated preterm birth occurs as a means to resolve maternal or fetal risk related to continuing the pregnancy. About 25% of all preterm births in the United States are indicated because of medical or obstetric conditions that affect the mother, the fetus, or both. An increase in the number of indicated preterm births between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation accounts for much of the recent rise in late preterm births (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009; Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Box 17-1 lists some common causes of indicated preterm births. The remainder of this section deals with spontaneous preterm labor and birth. Major risk factors for spontaneous preterm birth are listed in Box 17-2. Poverty, lack of education, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood, state, or region, and lack of access to prenatal care also have been identified as risk factors. In addition, the risk for preterm birth appears to be genetically related. For example, women who were themselves born prematurely have an increased risk for giving birth prematurely (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Researchers have developed many risk scoring systems in an attempt to determine which women might go into labor prematurely. No risk scoring system has been very successful in lowering the preterm birthrate, however, because at least 50% of all women who ultimately give birth prematurely have no identifiable risk factors (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009; Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Therefore it is important that all women be educated about prematurity, not only in early pregnancy but also in the preconception period. Unless all women are included in prevention efforts, a widespread reduction of preterm birthrates cannot be expected. Fetal fibronectin, a biochemical marker, has been studied extensively and is marketed in the United States as a diagnostic test for preterm labor. It is a glycoprotein “glue” found in plasma and produced during fetal life. Fetal fibronectin normally appears in cervical and vaginal secretions early in pregnancy and then again in late pregnancy. The test is performed by collecting fluid from the woman’s vagina using a swab during a speculum examination. The presence of fetal fibronectin during the late second and early third trimesters of pregnancy may be related to placental inflammation, which is thought to be one cause of spontaneous preterm labor. However, the presence of fetal fibronectin is not very sensitive as a predictor of preterm birth. Before 35 weeks of gestation, a positive fetal fibronectin test predicts preterm birth only about 25% of the time. The test’s sensitivity may be better earlier in pregnancy. In one study, the fetal fibronectin test predicted 65% of preterm births occurring before 28 weeks when it was performed between 22 and 24 weeks. Often the test is used to predict who will not go into preterm labor because preterm labor is very unlikely to occur in women with a negative result. Use of the fetal fibronectin test as a screening tool in women who are at low risk for preterm birth is not recommended (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). Another possible predictor of preterm labor is endocervical length. Changes in cervical length occur before uterine activity, so cervical measurement can identify women in whom the labor process has begun. However, because preterm cervical shortening occurs over a period of weeks, neither digital nor ultrasound cervical examination is very sensitive at predicting imminent preterm birth (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). Women whose cervical length is greater than 30 mm are unlikely to give birth prematurely even if they have symptoms of preterm labor (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009; Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Infection is definitely associated with preterm labor. Women in spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes commonly have organisms that are normally found in the lower genital tract present in their amniotic fluid, placenta, and membranes. Clinical and laboratory evidence of infection are more common when birth occurs earlier than 30 to 32 weeks of gestation rather than closer to term. Urinary tract and intraabdominal (e.g., appendicitis) infections have also been related to preterm birth (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Women with periodontal disease have been shown to have an increased risk for preterm birth. However, the risk is not reduced by periodontal care, suggesting that the link between periodontal disease and preterm birth is not a cause-and-effect relationship (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Another proposed cause of preterm labor and birth is bleeding at the site of placental implantation in the uterus in the first or second trimester of pregnancy. The resulting uteroplacental ischemia or hemorrhage at the decidual layer of the placenta may somehow activate the preterm labor process. Intrauterine inflammation is associated with infection, uterine vascular compromise, and decidual hemorrhage and may contribute to preterm labor. Maternal and fetal stress, uterine overdistention, allergic reaction, and a decrease in progesterone are other factors that may play a part in initiating preterm labor. It is becoming increasingly clear that preterm labor is caused by multiple pathologic processes that eventually result in uterine contractions, cervical changes, and membrane rupture (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009; Romero and Lockwood, 2009). Because all pregnant women must be considered at risk for preterm labor, nursing assessment for factors that contribute to this risk begins early in pregnancy and continues throughout the prenatal period. The onset of preterm labor is often insidious and can be easily mistaken for normal discomforts of pregnancy. Nursing diagnoses, expected outcomes of care, and evidence-based interventions are established for each woman based on her assessment findings (see Nursing Care Plan). Primary prevention strategies that address risk factors associated with preterm labor and birth are less costly in human and financial terms than the high-tech and often lifelong care required by preterm infants and their families. Programs aimed at health promotion and disease prevention that encourage healthy lifestyles for the population in general and women of childbearing age in particular should be developed. Preconception counseling and care for women, especially those with a history of preterm birth, may identify correctable risk factors and provide a means to encourage women to participate in health-promoting activities. Smoking cessation, for example, has been shown to prevent preterm labor and birth (Freda, 2006; Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). Preterm birth can be prevented in some women by administering prophylactic progesterone supplementation. Both daily vaginal suppositories or creams and weekly intramuscular injections of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate have been shown to decrease the rate of preterm birth by about 40% in women with a history of prior preterm birth or with a short (less than 15 mm to 20 mm length) cervix before 24 weeks of gestation. Supplementation begins at 16 weeks and continues until 36 weeks of gestation. Progesterone supplementation does not affect the rate of preterm birth in women with multiple gestations. Exactly how progesterone works to prevent preterm birth is unclear (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Many interventions intended to prevent spontaneous preterm birth have been recommended in the past and are still often prescribed. However, some of these interventions have not been shown to reduce the rate of preterm birth. Ongoing research is needed, especially since our understanding of the pathophysiology of preterm birth is increasing (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). Although preterm birth often is not preventable, early recognition of preterm labor is still essential to implement interventions that have been demonstrated to reduce neonatal and infant morbidity and mortality. These interventions include (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012): • Transferring the mother before birth to a hospital equipped to care for her preterm infant • Giving antibiotics during labor to prevent neonatal group B streptococci infection • Administering glucocorticoids to women in labor to prevent or reduce neonatal and infant morbidity and mortality from health problems including respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, and necrotizing enterocolitis • Administering magnesium sulfate to women giving birth before 32 weeks of gestation to reduce the incidence of cerebral palsy in their infants Although maternal transport helps ensure a better health outcome for the mother and the baby, it also has a downside. Women may be transported to tertiary centers far from home, making visits by family and friends difficult and increasing the anxiety levels of the woman and her family. Attention to the needs of the woman and her family before, during, and after the transport is essential to comprehensive nursing care. Because more than half of preterm births occur in women without obvious risk factors, it is essential that all pregnant women be taught the symptoms of preterm labor (Box 17-3). The nurse caring for women in a prenatal setting should use methods that are known to be successful for teaching pregnant women about how to recognize these symptoms and then assess for these symptoms at each prenatal visit. Women also must be taught the significance of these symptoms of preterm labor and what to do should they occur (see Patient Teaching box). In particular, patient education regarding any symptoms of uterine contractions or cramping between 20 and 37 weeks of gestation must emphasize that these symptoms are not just normal discomforts of pregnancy but, rather, indications of possible preterm labor (Fig. 17-1). Waiting too long to see a health care provider could result in inevitable preterm birth without sufficient time to implement the interventions that have been shown to improve infant outcomes (see preceding discussion). The diagnosis of preterm labor is based on three major diagnostic criteria: • Gestational age between 20 and 37 weeks • Uterine activity (e.g., contractions) • Progressive cervical change (e.g., effacement of 80% or cervical dilation of 2 cm or greater) If the presence of fetal fibronectin is used as another diagnostic criterion, a sample of cervical and vaginal secretions for testing should be obtained before an examination for cervical changes because the lubricant used to examine the cervix can reduce the accuracy of the test for fetal fibronectin. The presence of vaginal bleeding or ruptured membranes or a history of intercourse within the past 24 hours can also reduce the accuracy of the test results. Activity restriction, including bed rest and limited work, is a commonly prescribed intervention for the prevention of preterm birth. Bed rest, however, is not a benign intervention, and no evidence has been published in the literature to support the effectiveness of this intervention in reducing preterm birthrates (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Research indicates that bed rest causes adverse physical effects, including risk for thrombus formation, muscle atrophy, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular deconditioning. In many instances, these symptoms are not resolved by 6 weeks postpartum. In addition, bed rest affects women and their families psychologically, emotionally, socially, and financially. Box 17-4 lists adverse effects of bed rest. Many health care providers now recommend only modified bed rest. Restriction of sexual activity is frequently recommended for women at risk for preterm birth. This intervention has not been shown to be effective at preventing preterm birth. However, sexual abstinence has not been studied in women with specific risk factors for preterm birth, such as a short cervix. Therefore more research is indicated (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). If, however, symptoms of preterm labor occur after sexual activity, then that activity may need to be curtailed until 37 weeks of gestation. The woman’s environment can be modified for convenience by using tables and storage units around her bed or daytime resting place to keep essential items within reach (e.g., cell or smart phone, television, radio, MP3 player, CD player, computer with Internet access, snacks, books, magazines, newspapers, and items for hobbies) (Fig. 17-2). Ensuring that the bed or couch is near a window and the bathroom is also helpful. Covering the bed with an eggcrate mattress can relieve discomfort. Women often find that a daily schedule of smaller, more frequent meals, activities (e.g., paying bills, planning and helping with meal preparation, hobbies), limited naps, and hygiene and grooming (e.g., shower, dressing in street clothes, applying makeup) reduces boredom and helps them maintain control and normalcy. See the Patient Teaching box on p. 309 for more information. See the Patient Teaching box on p. 447 for additional ideas and suggestions. With modified bedrest, women are usually allowed bathroom privileges for toileting and showering and can be up to the table for meals. Tocolytics are medications given to arrest labor after uterine contractions and cervical change have occurred. No medications that have been approved for use as tocolytics by the United States Food and Drug Administration are currently available in the United States. Ritodrine (Yutopar) was approved but has been withdrawn from the market in the United States. However, it is still used as a tocolytic in other countries. Drugs marketed for other purposes, such as treatment of asthma or hypertension or as antiinflammatory or analgesic agents, are used on an “off-label” basis (i.e., drugs known to be effective for a specific purpose, although not specifically developed and tested for this purpose) to suppress preterm labor (Iams, Romero, and Creasy, 2009). No tocolytic has been shown to reduce the rate of preterm birth. Rather, the rationale for giving these medications is to delay birth long enough to allow time for maternal transport and for corticosteroids to reach maximum benefit to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality. Studies of individual drugs used for tocolysis rarely contain information about whether delaying birth improved infant outcomes (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). Maternal and fetal contraindications to tocolytic therapy are listed in Box 17-5. Box 17-6 describes nursing care for women receiving tocolytic therapy. Magnesium sulfate inhibits uterine contractions and decreases intracellular calcium levels (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012). It is almost always administered intravenously but can also be given intramuscularly. Magnesium sulfate produces few serious maternal or neonatal complications, and clinicians are familiar with its use. However, although magnesium sulfate is still frequently used, a recent meta-analysis of tocolytic agents found that it is not effective when given for tocolysis (see Medication Guide on pp. 448-449) (Simhan, Iams, and Romero, 2012).

Labor and Birth Complications

Preterm Labor and Birth

Preterm Birth versus Low Birth Weight

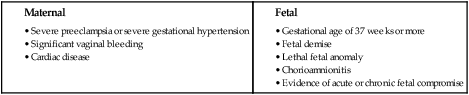

Spontaneous versus Indicated Preterm Birth

Predicting Spontaneous Preterm Labor and Birth

Fetal Fibronectin Test

Cervical Length

Causes of Spontaneous Preterm Labor and Birth

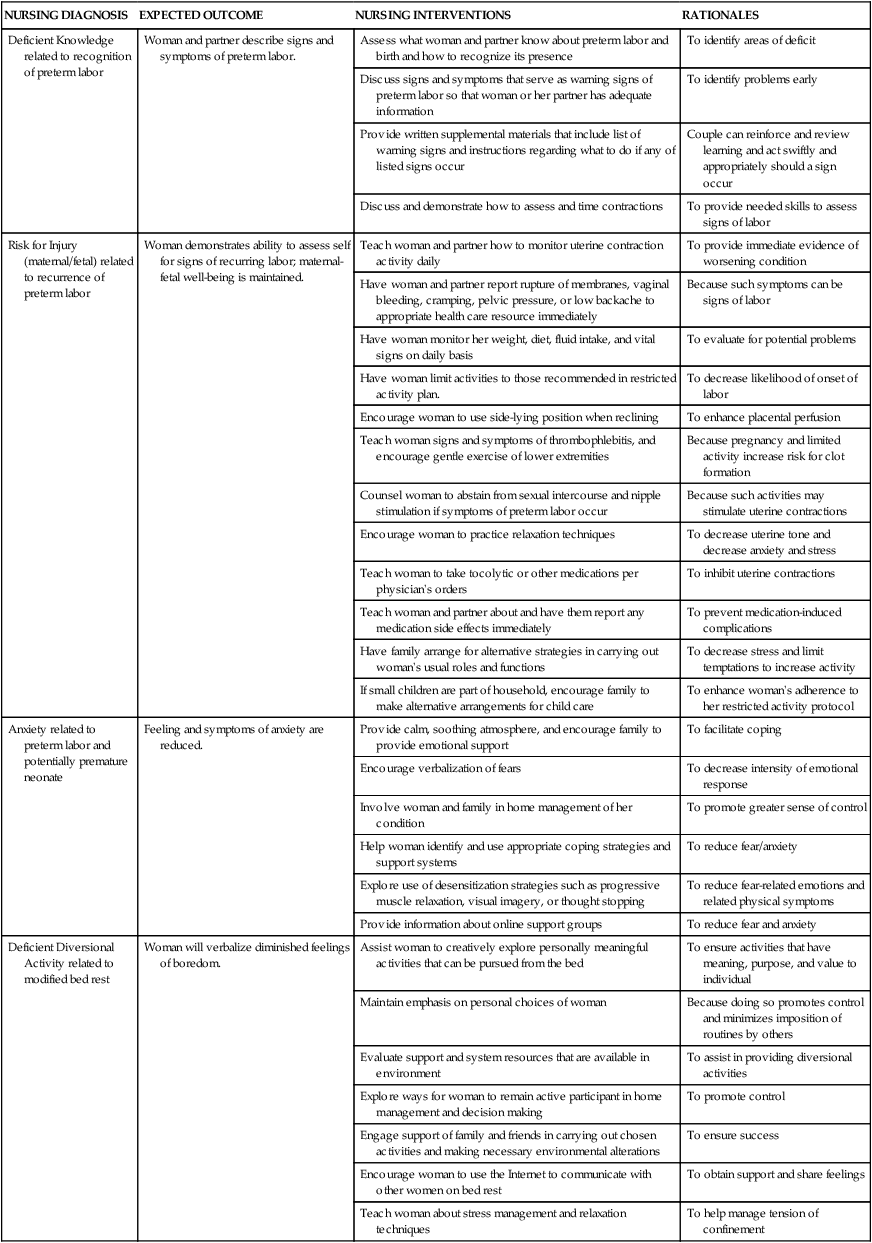

Care Management

Prevention

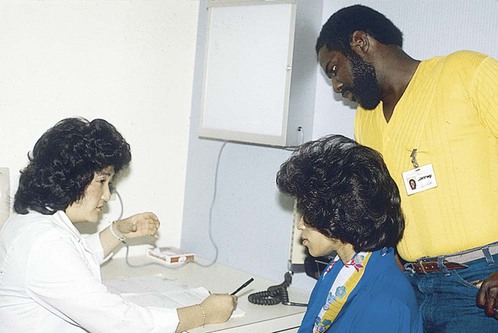

Early Recognition and Diagnosis

Lifestyle Modifications

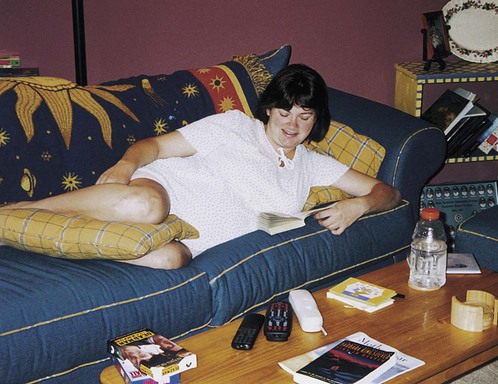

Activity Restriction.

Restriction of Sexual Activity.

Home Care.

Suppression of Uterine Activity