The five dimensions of health provide additional perspectives as CAM, dietary supplements, and medications interact with health. The physical health dimension can be affected when dietary supplements interact with medications and inadvertently alter the effects of medications. Intellectual health becomes valuable because critical thinking skills are required to assess the efficacy and appropriateness of incorporating alternative medicine therapies. Emotional health may be enhanced as complementary approaches address stress and anxiety that sometimes occur when dealing with chronic disorders. Social health can be supported by several alternative modalities, such as yoga and T’ai chi, which often involve classes that provide a social support group (Figure 16-1). The last dimension, spiritual health, can evolve by adopting modalities such as meditation and biofeedback, which provide physical and spiritual benefits by using the body to heal itself. CAM has become a significant component of health care in the United States. Consider that more than a third of Americans use CAM therapies, and others take herbal and dietary supplements that total a combined out-of-pocket cost of $27 billion per year.1 To address this increased interest in CAM, the National Institutes of Health created the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). For this discussion, the categories of CAM as outlined by NCCAM will be used. The CAM categories simplify the distinctions between the systems of healing and the related modalities but provide an adequate overview of the methods of application. According to NCCAM, complementary and alternative medicine consists of a cluster of medical and health care approaches, methods, and items not associated with conventional medicine.2 Medical doctors and doctors of osteopathy practice conventional medicine, which is also called allopathy, and Western medicine, as do other allied health professionals such as registered nurses, nurse practitioners, registered dietitians, and physician assistants. Some conventional physicians may also incorporate CAM in their practices. Studies of CAM therapies are being conducted; previously the efficacy of these therapies tended to be anecdotal based on the self-reported experiences of individuals. Some CAM systems such as Ayurveda, which includes the modality of yoga, and Traditional Chinese Medicine, which encompasses acupuncture, have been used for healing for thousands of years, thereby precluding the immediate need for “proof.” Nonetheless, well-designed studies are needed to continue to identify the efficacy of particular modalities for specific disorders (see the Cultural Considerations box, Global Strategies on Traditional and Alternative Medicine). Providing support for such studies is part of the mission of NCCAM. To continue with definitions, complementary medicine refers to non-Western healing approaches used at the same time as conventional medicine.2 For instance, a patient who attempts to lower hypertension takes prescription medications (conventional) but also attends yoga classes (complementary) for physical and psychologic benefits. In contrast, alternative medicine replaces conventional medical treatment.2 An example is the use of herbal supplements to treat cancer instead of surgical intervention or chemotherapy. Integrative medicine merges conventional medical therapies with CAM modalities for which safety and efficacy, based on scientific data, have been demonstrated.2 According to NCCAM, CAM therapies can be divided into five categories: alternative medical systems; mind-body interventions; biologically based therapies; manipulative and body-based methods; and energy therapies.2 Alternative medical systems develop outside mainstream Western medical approaches. These systems are based on holistic structures that incorporate distinctive philosophies and applications. Alternative medical systems evolving from Eastern cultures include Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Ayurveda (Asian Indian derivation). Western cultures have produced naturopathic medicine and homeopathic medicine.2 The Eastern practice of TCM is a system based on the forces of nature understood through the fundamental concept of yin and yang. Illness is viewed as an imbalance of these two forces that are opposites of each other. Yin is dark, night, feminine, and contracting; yang is light, day, masculine, and expanding. The imbalance of these two forces affects Qi, the life force. Therapeutic modalities, such as acupuncture, massage, meditation, incense, diet, herbs, and T’ai chi (exercise of slow movements), aim to reduce symptoms and restore energy balance. For example, acupuncture is the use of fine needles placed in the 2000 specific acupuncture points on the body to open blockages of the flow of Qi or life force and thus restore balance (Figure 16-2). The Eastern practice of Ayurveda is 5000 years old, evolving from the Indian subcontinent. As an alternative medical system, Ayurveda focuses on diet and herbal remedies that emphasize the use of body, mind, and spirit to prevent and treat disorders.2 The Western approach of naturopathic medicine is based on the use of the body’s natural healing forces to recover from disease and to achieve wellness.2 This system incorporates techniques from Eastern and Western traditions. Techniques may include acupuncture, exercise, massage, and dietary alterations. Homeopathic medicine is an alternative medical system through which a small amount of a diluted substance is prescribed to relieve symptoms for which the same substance, given in larger amounts, will cause the same symptoms. This theory is called “like cures like.”2 The focus of mind-body intervention is to expand the mind’s ability to influence physical functions. These modalities include meditation, faith healing or prayer, biofeedback, and such therapies that influence behavior through creative approaches of music, dance, and art therapy.2 Several of these modalities are commonly recommended and are used not only for physical healing but also for stress reduction and other concerns related to contemporary life. Meditation is a self-directed technique of relaxing the body and calming the mind. Based in Eastern religions, meditation evolved from religious practice. Meditation calms the mind and body through guided imagery and rhythmic breathing (Figure 16-3). Faith healing is healing by invoking divine intervention without the use of conventional or surgical therapy. Faith healing is a form of prayer that is either practiced individually or as a group; the practice is often associated with religious institutions or communities. Biofeedback involves the use of special devices to convey information about heart rate, blood pressure, skin temperature, and muscle relaxation to enable a person to learn how to consciously control these medically important functions. Patients need several training sessions to become able to produce the desired responses on their own. Biologically based therapies encompass materials found in nature. These materials include nutrients, food, and herbs. This category incorporates dietary supplements, alternative dietary patterns, aromatherapy, and other alternative natural treatments such as shark cartilage for cancer treatment.2 Dietary supplements are substances consumed orally as an addition to dietary intake (Figure 16-4). The ingredients of dietary supplements may include one or more of the following: minerals, vitamins, amino acids, herbs, plant extracts, enzymes, metabolites, and organ tissues.3 Dietary supplements are processed into various forms, including tablets, liquids, capsules, extracts, powders, concentrates, gel caps, liquids, and powders. There are special requirements for supplement labeling. Under the Dietary Supplement Act of 1994, dietary supplements are considered foods, not drugs.3 Because of the popularity of use, extensive range of supplements available, and connections to nutrition, the next section of this chapter explores supplements. Because all foods are categorized as yin or yang, dietary recommendations would, for example, support consumption of yang foods to offset a yin cancer. Also considered are the person’s age, sex, activity levels, and climate. Although the original macrobiotic diet consisted of a rigid 10-step program, the current version is not as restrictive and is health promoting. The core diet focuses on consumption of whole cereals and grains as 50% to 60% of intake with 40% to 50% from other foods, preferably organically grown, with minimal intake of animal foods except for small amounts of white fish. Consequently, intake of fatty foods, milk products, processed foods, and eggs are to be avoided because the belief is that such foods contain toxins that cause illness. Because this diet is low in fat and high in fiber and plant foods, it appears to support the health and recovery of individuals with cancer when used in conjunction with conventional treatments for cancer. The safety of the macrobiotic diet depends on the implementation to support sufficient intake of calories and nutrients. This requires substantial commitment to food preparation with planning to ensure nutrient adequacy.4 Aromatherapy is using extracts or essences of herbs, flowers, and trees in the form of essential oils to support health and well-being.2 The essential oils are added to candles, oils, and lotions through which the aroma is dispersed and inhaled with subsequent physiologic responses. Often, the essential oils are an integral part of massage therapy. Applications of aromatherapy continue to increase. Pillows can be purchased that have a special pocket in which to place essential oils to provide aromatherapy while one sleeps. A dental practice in New York City now offers aromatherapy along with foot massages to decrease stress while dental procedures are conducted.5 In a number of breast cancer treatment centers, nurses use essential oils and massage to reduce anxiety and discomfort of patients during chemotherapy treatments. Osteopathic manipulation is a part of osteopathic medicine. Although osteopathic medicine is considered part of conventional medicine, it differs in its view of disease as stemming from the musculoskeletal system.2 This approach is based on the assumption that the systems of the body function together. Therefore, disturbances in one system may affect other systems. Some osteopathic physicians conduct osteopathic manipulation, which is a method of hands-on actions to reduce pain, reinstate function, and promote health and well-being.2 Chiropractic manipulation addresses the ties between body structure (particularly of the spine) and function and how those ties affect the maintenance and return to health.2 Manipulative therapy is the foundation of treatment.2 Biofield therapies include Qi gong, reiki, and therapeutic touch. Qi gong is a modality of TCM that merges breathing regulation, movement, and meditation to increase the flow of Qi or life force in the body. This practice of Qi gong enhances circulatory and immune function.2 Reiki means “universal life energy” in Japanese. The energy therapy bearing the name “reiki” is based on the belief that by healing the patient’s spirit, the physical body will also heal. Spirits are healed when a reiki practitioner channels spiritual energy, or universal life force, through to the patient.2 Therapeutic touch is a version of the ancient technique called laying-on of hands. Therapeutic touch is based on facilitating the flow of energy in and around the body. The therapist proceeds to identify and undo blockages to promote healing. Therapists, while in a meditative state, move their hands above patients to determine blockages in energy fields and then clear blockages by the downward motions of their hands around, but not actually touching, the patients’ bodies. The healing energy powers of therapists are transferred to patients to restore energy balance within their bodies.2 Bioelectromagnetic-based therapies consist of the unusual use of electromagnetic fields. These fields include magnetic fields, pulsed fields, and direct or alternating current fields.2 Although magnets have been used for a long time as healing tools, the efficacy of their use has not, as yet, been validated. Knowledge of nutrients began to be discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century. First, the role of vitamins in preventing deficiency diseases was revealed. More recently, other nutrient-related substances such as concentrated garlic, fish oils, and psyllium came into use for believed health benefits. The concept of dietary supplements evolved because of the growing body of knowledge resulting in the availability of substances in the form of pills, powder, and liquid to enhance the quality of dietary intakes.6 As the effects of nutrients on health continued to be learned, knowledge of the inappropriate eating habits of Americans increased. Consequently, the value of dietary supplements to rectify poor eating habits caught the attention of the American public as an easier way to improve health than by changing eating behavior. Throughout this time, physicians tended to discount the value of dietary supplements, including vitamin supplementation. Instead, physicians and dietitians strongly recommended that all nutrients be consumed through food rather than supplements.6 The view of supplementation of essential nutrients has changed somewhat during the past few years. Supplements may be recommended as a safety net for poor dietary intake. As a safety net, vitamin/mineral supplements at 100% or less of the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) are appropriate. Additional vitamin/mineral supplements are also recommended for some specific nutrients for certain subgroups within the population. For example, calcium and vitamin D supplementation is suggested for adults older than 70 years because the new DRI for calcium and vitamin D for this age group is higher than what most individuals can generally consume. DSHEA establishes a definition of dietary supplements as products that supplement dietary intake and contain one or more of the following:3 • A dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake • A concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or a combination of the preceding ingredients If a manufacturer distributes a product containing a new dietary ingredient, the manufacturer must notify the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 75 days before the product is to be released. In addition, the manufacturer must also provide data regarding the safety and efficacy of the product. Supplements already on the market or supplement ingredients previously used are considered generally safe and do not need reapproval.3 Labeling of dietary supplements must follow the format used for nutrition labels (see Chapter 2). This means that the label needs to identify the product as a dietary supplement and must include the name and amount of each item contained in the product. Labels may also include approved statements of health claims such as are allowable on food product labels. For example, a claim may be made that a diet containing soluble fiber from whole oats and psyllium may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease. Other health-related claims may also be made about the effect of the supplement on the “structure or function” of the body as well as on “general well-being.” Claims related to reducing the risk of nutrition deficiency diseases are also acceptable. In addition, if claims are made, the label must include the statement “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”3 In the past, use of supplements was limited to a small group of individuals, and supplements were available in an equally small number of locations such as health food stores and specialty shops. Currently, supplements are available through numerous outlets including supermarkets, drugstores, mail-order companies, and Internet websites. Sales of dietary supplements have increased tremendously from about $8 billion in 1994 to an estimated $24 billion in 2010.7 Consider that the reason for the increased use of dietary supplements is that consumers have self-care goals for which dietary supplements provide perceived value. Concurrently, such self-care goals may reflect consumers experiencing alienation from conventional health care systems.3 This alienation may be why patients do not reveal their use of dietary supplements to their health care providers. About 22.8 million consumers use herbal supplements rather than prescription drugs, and 19.6 million use herbs with prescription medications.3 These consumers may either view the dietary supplements as not really “medicine” or fear that their health care providers might not approve of their self-care goals. Not revealing supplement use may result in misuse of substances or interaction with prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs (Table 16-1). Consequently, it is most important to question patients in detail to ascertain use of supplements beyond prescription medications. TABLE 16-1 From Long S: Drug-nutrient interactions. In Schlenker ED, Long S, editors: Williams’ essentials of nutrition & diet therapy, ed 10, St. Louis, 2010, Mosby. Data from Kuhn MA, Winston D: Herbal therapy and supplements. a scientific and traditional approach, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2007, Lippincott; Kemper K, Gardiner P, Chan E: “At least it’s natural.” Herbs and dietary supplements in ADHD, Contemp Pediatr 9:116-130, 2000. Accessed April 11, 2009, from www.contemporarypediatrics.com; Kemper K, Gardiner P, Conboy LA: Herbs and adolescent girls: avoiding the hazards of self-treatment, Contemp Pediatr 3:133-154, 2000. Accessed April 11, 2009, from www.contemporarypediatrics.com. Some functional food components are marketed as dietary supplements, such as herb-enriched beverages. Care must be taken, though, because the amounts and sources of herb and other phytochemical ingredients are not sufficiently regulated.8 A fruit juice beverage may contain the herb St. John’s wort, which may be effective for the treatment of mild depression, but it must be taken regularly for several months for a response to occur. Consuming a small amount in a juice beverage is ineffective for depression treatment and pointless for any other purpose. Health professionals can be aware of the range of products available and advise patients accordingly based on basic principles of good health. As the public becomes more educated about phytochemicals as a natural component of whole foods, perhaps the perception of dietary supplements will change. For example, tomatoes naturally contain lycopene, a phytochemical. Instead of taking a supplement containing lycopene, consumption of tomatoes would provide the same benefit. Nonetheless, the development of functional foods will continue because of several factors. These factors include (1) an aging population concerned about health; (2) increased cost of health care; (3) growth of self-care regarding health; (4) continued evidence of the affect of dietary intake on disease prevention and treatment; and (5) changes in food regulation that appear to support the expanded growth of dietary supplements and functional foods.8 Referral to registered dietitians for nutrition therapy involving dietary supplements or for general nutrition counseling is always an option. Health professionals and the public can consult the American Dietetic Association’s website (www.eatright.org) for guidance on meeting specific health promotion or nutrition therapy goals. Registered dietitians are trained to consider several factors when advising on nutrient and other dietary supplements. Factors considered include the level of scientific evidence available on the substance, demographics (i.e., age, gender), disease states, clinical parameters (e.g., blood pressure and weight), medications (prescribed and OTC) currently used, and risks or benefits of the substance. Dietary supplements should always be complementary to a sound diet. Dietary intake should first be adjusted to fulfill nutrient gaps before dietary supplements are used.9 All drugs produce physiologic effects; some of these effects are unintended (side effects) and constitute the risks of medication use. The amount and rate of drug absorption can be affected by the composition and timing of food intake. Conversely, food intake, absorption, and metabolism can be altered by medication. Drug-nutrient interactions have the potential to reduce drug efficacy, interfere with disease control, foster nutritional deficiencies, influence food intake, or provoke a toxic reaction.10 The Joint Commission (TJC) strongly recommends evaluation of drug and diet combinations. Documentation of these interactions, which may be done by the registered dietitian or nurse, is essential in complying with TJC standards. In addition to medications, use of alcohol and street drugs also affect nutritional status and nutrient requirements.

Interactions

Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Dietary Supplements, and Medications

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Role in Wellness

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Alternative Medical Systems

Mind-Body Interventions

Biologically Based Therapies

Manipulative and Body-Based Methods

Energy Therapies

Dietary Supplements

Regulation and Labeling

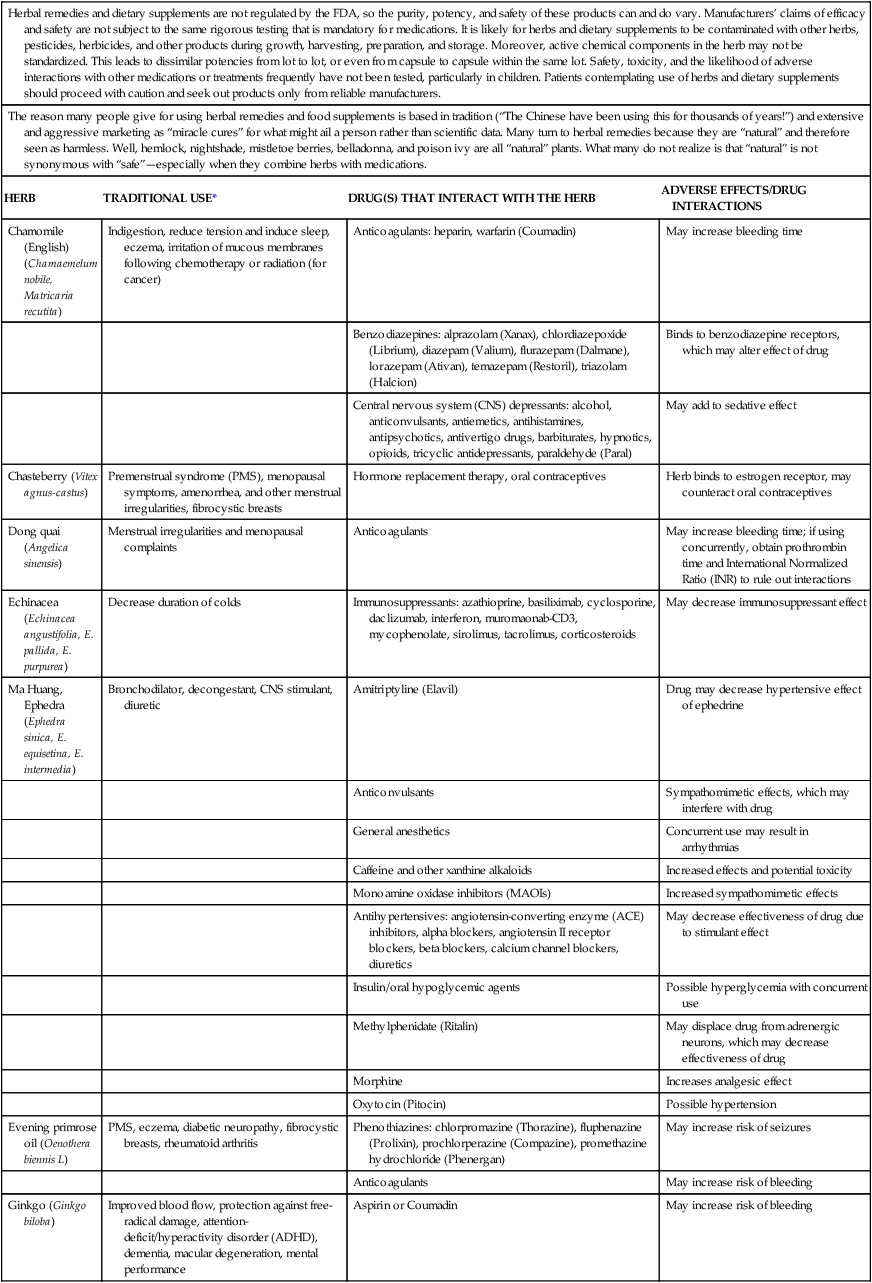

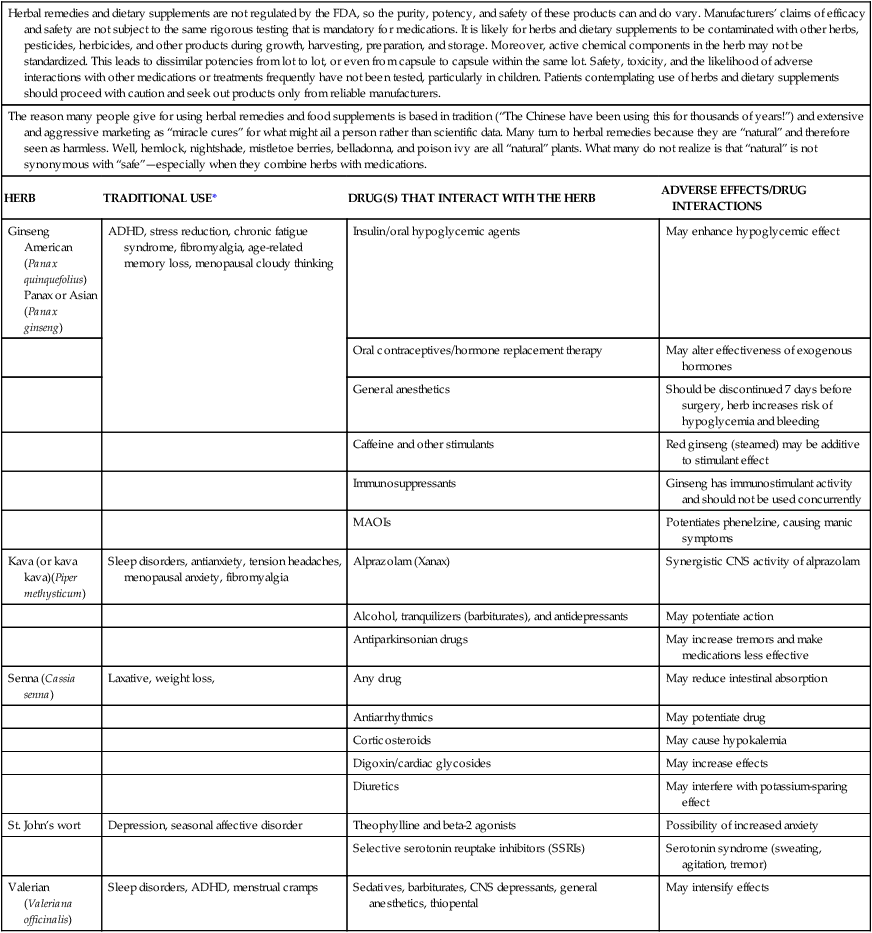

Supplement Use

Herbal remedies and dietary supplements are not regulated by the FDA, so the purity, potency, and safety of these products can and do vary. Manufacturers’ claims of efficacy and safety are not subject to the same rigorous testing that is mandatory for medications. It is likely for herbs and dietary supplements to be contaminated with other herbs, pesticides, herbicides, and other products during growth, harvesting, preparation, and storage. Moreover, active chemical components in the herb may not be standardized. This leads to dissimilar potencies from lot to lot, or even from capsule to capsule within the same lot. Safety, toxicity, and the likelihood of adverse interactions with other medications or treatments frequently have not been tested, particularly in children. Patients contemplating use of herbs and dietary supplements should proceed with caution and seek out products only from reliable manufacturers.

The reason many people give for using herbal remedies and food supplements is based in tradition (“The Chinese have been using this for thousands of years!”) and extensive and aggressive marketing as “miracle cures” for what might ail a person rather than scientific data. Many turn to herbal remedies because they are “natural” and therefore seen as harmless. Well, hemlock, nightshade, mistletoe berries, belladonna, and poison ivy are all “natural” plants. What many do not realize is that “natural” is not synonymous with “safe”—especially when they combine herbs with medications.

HERB

TRADITIONAL USE*

DRUG(S) THAT INTERACT WITH THE HERB

ADVERSE EFFECTS/DRUG INTERACTIONS

Chamomile (English)(Chamaemelum nobile, Matricaria recutita)

Indigestion, reduce tension and induce sleep, eczema, irritation of mucous membranes following chemotherapy or radiation (for cancer)

Anticoagulants: heparin, warfarin (Coumadin)

May increase bleeding time

Benzodiazepines: alprazolam (Xanax), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), diazepam (Valium), flurazepam (Dalmane), lorazepam (Ativan), temazepam (Restoril), triazolam (Halcion)

Binds to benzodiazepine receptors, which may alter effect of drug

Central nervous system (CNS) depressants: alcohol, anticonvulsants, antiemetics, antihistamines, antipsychotics, antivertigo drugs, barbiturates, hypnotics, opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, paraldehyde (Paral)

May add to sedative effect

Chasteberry (Vitex agnus-castus)

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS), menopausal symptoms, amenorrhea, and other menstrual irregularities, fibrocystic breasts

Hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptives

Herb binds to estrogen receptor, may counteract oral contraceptives

Dong quai (Angelica sinensis)

Menstrual irregularities and menopausal complaints

Anticoagulants

May increase bleeding time; if using concurrently, obtain prothrombin time and International Normalized Ratio (INR) to rule out interactions

Echinacea (Echinacea angustifolia, E. pallida, E. purpurea)

Decrease duration of colds

Immunosuppressants: azathioprine, basiliximab, cyclosporine, daclizumab, interferon, muromaonab-CD3, mycophenolate, sirolimus, tacrolimus, corticosteroids

May decrease immunosuppressant effect

Ma Huang, Ephedra (Ephedra sinica, E. equisetina, E. intermedia)

Bronchodilator, decongestant, CNS stimulant, diuretic

Amitriptyline (Elavil)

Drug may decrease hypertensive effect of ephedrine

Anticonvulsants

Sympathomimetic effects, which may interfere with drug

General anesthetics

Concurrent use may result in arrhythmias

Caffeine and other xanthine alkaloids

Increased effects and potential toxicity

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

Increased sympathomimetic effects

Antihypertensives: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, alpha blockers, angiotensin II receptor blockers, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics

May decrease effectiveness of drug due to stimulant effect

Insulin/oral hypoglycemic agents

Possible hyperglycemia with concurrent use

Methylphenidate (Ritalin)

May displace drug from adrenergic neurons, which may decrease effectiveness of drug

Morphine

Increases analgesic effect

Oxytocin (Pitocin)

Possible hypertension

Evening primrose oil (Oenothera biennis L)

PMS, eczema, diabetic neuropathy, fibrocystic breasts, rheumatoid arthritis

Phenothiazines: chlorpromazine (Thorazine), fluphenazine (Prolixin), prochlorperazine (Compazine), promethazine hydrochloride (Phenergan)

May increase risk of seizures

Anticoagulants

May increase risk of bleeding

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba)

Improved blood flow, protection against free-radical damage, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dementia, macular degeneration, mental performance

Aspirin or Coumadin

May increase risk of bleeding

Ginseng American (Panax quinquefolius)

Panax or Asian (Panax ginseng)

ADHD, stress reduction, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, age-related memory loss, menopausal cloudy thinking

Insulin/oral hypoglycemic agents

May enhance hypoglycemic effect

Oral contraceptives/hormone replacement therapy

May alter effectiveness of exogenous hormones

General anesthetics

Should be discontinued 7 days before surgery, herb increases risk of hypoglycemia and bleeding

Caffeine and other stimulants

Red ginseng (steamed) may be additive to stimulant effect

Immunosuppressants

Ginseng has immunostimulant activity and should not be used concurrently

MAOIs

Potentiates phenelzine, causing manic symptoms

Kava (or kava kava)(Piper methysticum)

Sleep disorders, antianxiety, tension headaches, menopausal anxiety, fibromyalgia

Alprazolam (Xanax)

Synergistic CNS activity of alprazolam

Alcohol, tranquilizers (barbiturates), and antidepressants

May potentiate action

Antiparkinsonian drugs

May increase tremors and make medications less effective

Senna (Cassia senna)

Laxative, weight loss,

Any drug

May reduce intestinal absorption

Antiarrhythmics

May potentiate drug

Corticosteroids

May cause hypokalemia

Digoxin/cardiac glycosides

May increase effects

Diuretics

May interfere with potassium-sparing effect

St. John’s wort

Depression, seasonal affective disorder

Theophylline and beta-2 agonists

Possibility of increased anxiety

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Serotonin syndrome (sweating, agitation, tremor)

Valerian (Valeriana officinalis)

Sleep disorders, ADHD, menstrual cramps

Sedatives, barbiturates, CNS depressants, general anesthetics, thiopental

May intensify effects

Looking to the Future

Application to Nursing

Medications

Drug-Nutrient Interactions

Interactions: Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Dietary Supplements, and Medications

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access