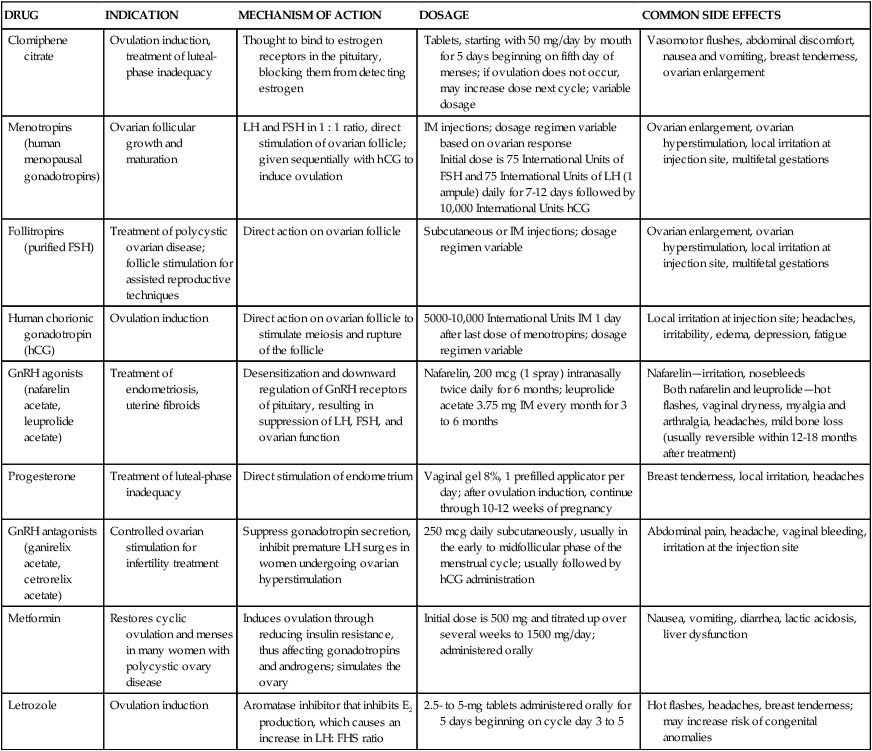

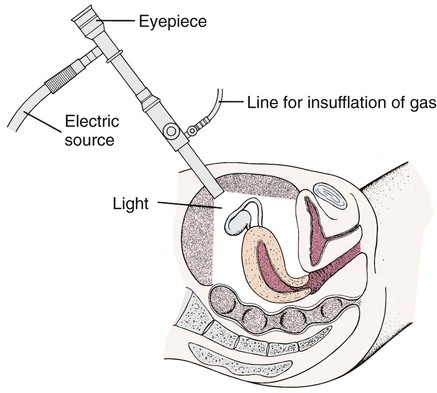

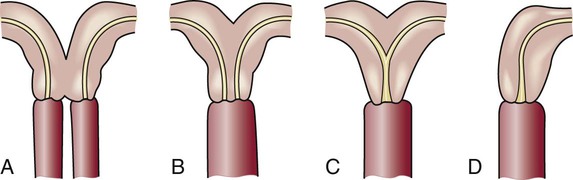

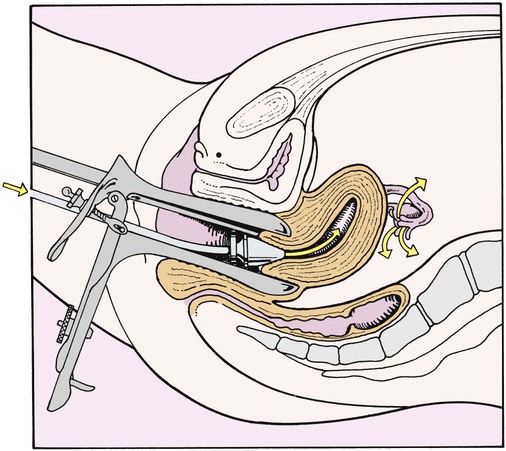

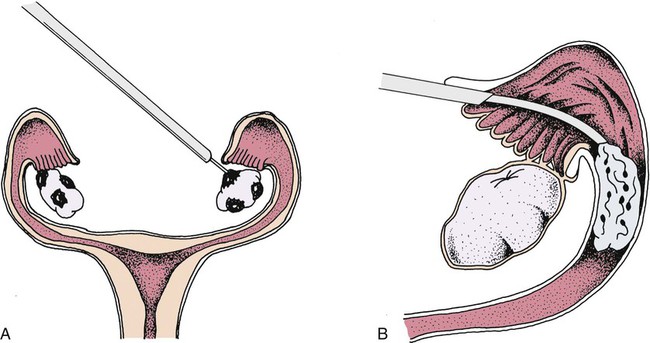

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • List common causes of infertility. • Discuss the psychologic impact of infertility. • Describe common diagnoses and treatments for infertility. • Compare reproductive alternatives for couples experiencing infertility. • Identify the advantages and disadvantages of the following methods of contraception: fertility awareness methods, barrier methods, hormonal methods, intrauterine devices, and sterilization. • Explain common nursing interventions that facilitate contraceptive use. • Describe the techniques used for medical and surgical interruption of pregnancy. • Recognize ethical, legal, cultural, and religious considerations of infertility, contraception, and elective abortion. Infertility is a serious concern that affects quality of life of 10% to 15% of reproductive-age couples (American Society for Reproductive Medicine [ASRM], 2012). Commonly infertility is considered to be a diagnosis for couples who have not achieved pregnancy after 1 year of regular, unprotected intercourse when the woman is less than 35 years of age or after 6 months when the woman is older than 35 (Practice Committee of the ASRM, 2008). Fecundity is the term used to describe the chance of achieving pregnancy and subsequent live birth within one menstrual cycle. Fecundity averages 20% in couples who are not experiencing reproductive problems. For the couple experiencing infertility, diagnosis and treatment strategies require considerable physical, emotional, and financial investment over an extended period of time. Feelings connected with infertility are many and complex. The origins of some of these feelings are myths, superstitions, misinformation, or magical thinking about the causes of infertility. Other feelings of anxiety and helplessness arise from the need to undergo many tests and examinations and from a perception of being “different” from others (RESOLVE, 2012). Nurses who care for infertile couples should consider the following four goals: • Provide the couple with accurate information about human reproduction, infertility treatments, and prognosis for pregnancy. Dispel any myths or inaccuracies from friends or the mass media that the couple may believe to be true. • Help the couple and the health care team accurately identify and treat possible causes of infertility. • Provide emotional support. The couple may benefit from anticipatory guidance, counseling, and support group meetings, either face-to-face or online. The organization RESOLVE (www.resolve.org) provides online support, advocacy, and education about infertility for both the infertility community and health care providers. • Guide and educate those who fail to conceive biologically as a couple about other forms of treatment such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), donor eggs or semen, surrogate motherhood, and adoption. Support the couple in their decisions regarding their future family. Nurses should also remember that among healthy women and men promotion of normal reproduction and prevention of infertility can be achieved if both partners maintain a normal body mass index (BMI) and avoid sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and exposures to substances or habits (such as smoking) that impair reproductive ability. As they make plans for their future family, adults should also know that realistically fertility decreases with age. Although exact percentages vary somewhat with populations, approximately 80% of couples have an identifiable cause of infertility, with about 40% of these causes related to factors in the female partner, 40% related to factors in the male partner, and 20% related to factors in both partners. About 20% or more couples will experience unexplained or idiopathic causes of infertility (ASRM, 2012). Nevertheless the focus of infertility treatment has shifted from attempting to correct a specific pathology to recommending and initiating the treatment that is most effective in achieving pregnancy for this unique couple at this time in their reproductive life span. Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) have proven to be effective, even in couples who experience unexplained infertility. • The male must deposit semen with sperm that has the capacity to fertilize an egg close to the cervix at the time of ovulation. The sperm must be able to ascend through the uterus and fallopian tubes (male factor). • The cervix must be sufficiently open to allow semen to enter the uterus and provide a nurturing environment for sperm (cervical factor). • The fallopian tubes must be able to capture the ovum, transport semen to the ovum, and transport the fertilized embryo to the uterus (tubal factor). • Ovulation of a healthy oocyte must occur, ideally within the parameters of a regular, predictable menstrual cycle (ovarian factor). • The uterus must be receptive to implantation of the embryo and capable of nourishing the growth and development of the fetus throughout the normal duration of pregnancy (uterine factor). An alteration in one or more of these structures, functions, or processes results in some degree of impaired fertility. Boxes 5-1 and 5-2 list factors affecting female and male infertility. For ovulation to occur, both partners must have normal, intact hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal hormonal axes that support the formation of sperm in the male and ova in the female. Sperm can remain viable within a woman’s reproductive tract for at least 3 days and for as long as 5 days. The oocyte can only be successfully fertilized for 12 to 24 hours after ovulation (Fritz and Speroff, 2011c). The couple seeking pregnancy should be taught about the menstrual cycle and ways to detect ovulation (see Chapter 3). They should be counseled to have intercourse 2 to 3 times a week; or, if timed intercourse does not increase anxiety, they should be encouraged to engage in intercourse the day before and the day of ovulation. Fertility decreases markedly 24 hours after ovulation. The nurse assists in the assessment and education of the infertile couple. As part of the assessment process he or she obtains information from the couple through interview and physical examination, including if this couple’s situation is one of primary (never experienced pregnancy) or secondary (previous pregnancy) infertility. Religious, cultural, and ethnic data may place restrictions on use of available treatments. Box 5-3 describes some of the concerns related to religion that may affect the couple’s choices regarding infertility treatment. The Cultural Competence box notes cultural rituals and beliefs regarding fertility. In addition, the nurse obtains and monitors results of diagnostic testing. Some of the information and data needed to investigate impaired fertility are of a sensitive, personal nature. The couple may experience feelings of invasion of privacy, and the nurse must exercise tact and express concern for their well-being throughout the interview. The tests and examinations associated with infertility diagnosis and treatment are occasionally painful and often intrusive. The couple’s intimacy and feelings of romantic attachment are often impaired as they engage in this process. A high level of motivation is needed to endure the investigation and subsequent treatment. Because multiple factors involving both partners are common, the investigation of impaired fertility is conducted systematically and simultaneously for both male and female partners (see Cultural Competence box). Both partners must be interested in the solution to the problem. The medical investigation requires time (3 to 4 months) and considerable financial expense. Box 5-4 describes the status of insurance coverage for infertility treatment. Evaluation for infertility should be offered to couples who have failed to become pregnant after 1 year of regular intercourse or after 6 months if the woman is over 35. Investigation of impaired fertility begins for the woman with a complete history and physical examination. A complete general physical examination should include height and weight and estimation of BMI. Both obesity and being underweight are associated with anovulation disorders. Signs and symptoms of androgen excess such as excess body hair or pigmentation changes should be noted. The general physical examination is followed by a specific assessment of the reproductive tract. A history of infections of the genitourinary tract and any signs of infections, especially STIs that could impair tubal patency, should be assessed. Bimanual examination of internal organs may reveal lack of mobility of the uterus or abnormal contours of the uterus and tubes. A woman may have an abnormal uterus and tubes (Fig. 5-1) as a result of congenital abnormalities during fetal development). These uterine abnormalities increase risk for early pregnancy loss. The basic infertility survey of the female involves evaluation of the cervix, uterus, tubes, and peritoneum; detection of ovulation; and hormone analysis. Timing and descriptions of common tests are presented in Table 5-1. Previous status regarding ovulation can be evaluated through menstrual history, serum hormone studies, and use of an ovulation predictor kit. If the woman is over age 35, the clinician may choose to assess “ovarian reserve” or how many potential ova remain within the ovaries. A common evaluation of ovarian reserve is measurement of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels on the third day of the menstrual cycle. The uterus and fallopian tubes can be visualized for abnormalities and tubal patency through hysterosalpingogram (x-ray film examination of the uterine cavity and tubes after instillation of radiopaque contrast material through the cervix). If the woman is at risk for endometriosis (implants of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus) or adhesions, diagnostic laparoscopy may be indicated. Test findings favorable for fertility are summarized in Box 5-5. TABLE 5-1 GENERAL TESTS FOR IMPAIRED FERTILITY Semen is collected by ejaculation into a clean container or a plastic sheath that does not contain a spermicidal agent. The specimen is usually collected by masturbation following 2 to 7 days of abstinence from ejaculation. The semen is examined at the collection site or taken to the laboratory in a sealed container within 2 hours of ejaculation. Exposure to excessive heat or cold is avoided. Commonly accepted values for semen characteristics are given in Box 5-6. If results are in the fertile range, no further sperm evaluation is necessary. If results are not within this range, the test is repeated. If subsequent results are still in the subfertile range, further evaluation is needed to identify the problem. If the couple does not conceive, they should be assessed regarding their desire to be referred for help with adoption, donor eggs or semen, surrogacy, or other reproductive alternatives. The couple may choose to continue in a childfree state. Both health care providers and patients should have a list of agencies, support groups, and other resources within their community such as the ASRM (www.asrm.org) and RESOLVE (www.resolve.org). Hysterosalpingography is useful for identification of tubal obstruction and also for the release of blockage as demonstrated in Fig. 5-2. During laparoscopy delicate adhesions may be divided and removed, and endometrial implants may be destroyed by electrocoagulation or laser, as illustrated in Fig. 5-3. Laparotomy and microsurgery may be required for extensive repair of the damaged tube. Prognosis depends on the degree to which tubal patency and function can be restored. In general laparoscopic surgery for tubal patency is most effective in younger women with distal tubal damage. Older women or those with significant proximal disease should be referred for ARTs that bypass the fallopian tube. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2012) defines assisted reproductive technology (ART) as fertility treatments in which both eggs and sperm are handled. In general these treatments involve removing the eggs from the woman, fertilizing the eggs in the laboratory, and returning the embryo or embryos to the woman or surrogate carrier. The CDC reported that in 2010 there were approximately 147,260 ART cycles with 47,090 births and 61,564 infants (some multiple births) from these cycles. Although the use of ART is still relatively rare compared to the potential demand, its use has doubled over the past decade. Births that were conceived through ART comprise over 1% of all infants born in the United States every year. Some of the ARTs for treatment of infertility include in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer (IVF-ET), gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) (Fig. 5-4), zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT), ovum transfer (oocyte donation), embryo adoption, embryo hosting and surrogate motherhood, therapeutic donor insemination (TDI), intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), assisted embryo hatching, and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). Table 5-2 describes these procedures and the possible indications for ARTs. Donor sperm and donor eggs can be used with ARTs. In addition, surrogates may carry the couple’s biologic child. ARTs are associated with many ethical and legal issues (Box 5-7). TABLE 5-2 ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE THERAPIES Data from American Society for Reproductive Medicine: Assisted reproductive technologies, 2011, www.asrm.org. PGD is a form of early genetic testing designed to eliminate embryos with serious genetic diseases before implantation through one of the ARTs and to avoid future termination of pregnancy for genetic reasons. Micromanipulation allows removal of a single cell from a multicellular embryo for genetic study (i.e., embryo biopsy) (Fritz and Speroff, 2011c). PGD is used clinically in over 20 centers around the world. Couples must be counseled about their options and choices and the implications of their choices when genetic analysis is considered.

Infertility, Contraception, and Abortion

Infertility

Incidence

Factors Associated with Infertility

Care Management

Assessment of Female Infertility

Diagnostic Testing.

TEST OR EXAMINATION

TIMING (MENSTRUAL CYCLE DAYS)

RATIONALE

Hysterosalpingogram (HSG) (uterine abnormalities, tubal patency)

7-10

Late follicular, early proliferative phase; will not disrupt a fertilized ovum; may open uterine tubes before time of ovulation

Chlamydia immunoglobulin G antibodies (tubal patency)

Variable

Negative antibody test may indicate tubal patency assessment (HSG); not needed in low risk women

Hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography (uterine abnormalities, tubal patency)

7-10

Late follicular, early proliferative phase; will not disrupt a fertilized ovum; evaluates tubal patency, uterine cavity, and myometrium

Serum progesterone (ovulation)

7 days before expected menses

Midluteal-phase progesterone levels; check adequacy of corpus luteum progesterone production

Assessment of cervical mucus (ovulation)

Variable, ovulation

Cervical mucus should have low viscosity, high spinnbarkeit (ability to stretch) during ovulation

Basal body temperature (ovulation)

Chart entire cycle

Elevation occurs in response to progesterone; documents ovulation

Urinary ovulation predictor kit (ovulation)

Variable, ovulation

Detects timing of lutein hormone surge before ovulation

Semen analysis (male factor)

2 to 7 days after abstinence

Detects ability of sperm to fertilize egg

Sperm penetration assay (male factor)

After 2 days but ≤1 wk of abstinence

Evaluation of ability of sperm to penetrate egg

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level (ovarian reserve)

Day 3

High FSH levels (>20) indicate that pregnancy will not occur with woman’s own eggs; value <10 indicates adequate ovarian reserve

Clomiphene citrate challenge test (CCCT) (ovarian reserve)

Administer clomiphene 100 mg days 3 through 10

Assess FSH on days 3 and 10 in presence of clomiphene stimulation; high FSH levels (>20) indicate that pregnancy will not occur with woman’s own eggs; FSH <15 suggestive of adequate ovarian reserve

Assessment of Male Infertility

Diagnostic Testing and Semen Analysis.

Psychosocial Considerations

Surgical Therapies

Assisted Reproductive Therapies

PROCEDURE

DEFINITION

INDICATIONS

In vitro fertilization–embryo transfer (IVF-ET)

A woman’s eggs are collected from her ovaries, fertilized in the laboratory with sperm, and transferred to her uterus after normal embryo development has occurred.

Tubal disease or blockage; severe male infertility; endometriosis; unexplained infertility; cervical factor; immunologic infertility

Gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT)

Oocytes are retrieved from the ovary, placed in a catheter with washed motile sperm, and immediately transferred into the fimbriated end of the uterine tube. Fertilization occurs in the uterine tube.

Same as for IVF-ET, except there must be normal tubal anatomy, patency, and absence of previous tubal disease in at least one uterine tube

IVF-ET and GIFT with donor sperm

This process is the same as described previously except in cases where the husband’s fertility is severely compromised and donor sperm can be used; if donor sperm are used, the wife must have indications for IVF and GIFT.

Severe male infertility; azoospermia; indications for IVF-ET or GIFT

Zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT)

This process is similar to IVF-ET; after IVF the ova are placed in one uterine tube during the zygote stage.

Same as for GIFT

Donor oocyte

Eggs are donated by an IVF procedure, and the donated eggs are inseminated. The embryos are transferred into the recipient’s uterus, which is hormonally prepared with estrogen/progesterone therapy.

Early menopause; surgical removal of ovaries; congenitally absent ovaries; autosomal or sex-linked disorders; lack of fertilization in repeated IVF attempts because of subtle oocyte abnormalities or defects in oocyte-spermatozoa interaction

Donor embryo (embryo adoption)

A donated embryo is transferred to the uterus of an infertile woman at the appropriate time (normal or induced) of the menstrual cycle.

Infertility not resolved by less aggressive forms of therapy; absence of ovaries; male partner azoospermic or severely compromised

Gestational carrier (embryo host); surrogate mother

A couple undertakes an IVF cycle, and the embryo(s) is/are transferred to another woman’s uterus (the carrier), who has contracted with the couple to carry the baby to term. The carrier has no genetic investment in the child.

Surrogate motherhood is a process by which a woman is inseminated with semen from the infertile woman’s partner and then carries the baby until birth.

Congenital absence or surgical removal of uterus; reproductively impaired uterus, myomas, uterine adhesions, or other congenital abnormalities; medical condition that might be life threatening during pregnancy (e.g., diabetes; immunologic problems; or severe heart, kidney, or liver disease)

Therapeutic donor insemination (TDI)

Donor sperm are used to inseminate the female partner.

Male partner is azoospermic or has very low sperm count; couple has genetic defect; male partner has antisperm antibodies

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

One sperm cell is selected to be injected directly into the egg to achieve fertilization. It is used with IVF.

Same as TDI

Assisted hatching

The zona pellucida is penetrated chemically or manually to create an opening for the dividing embryo to hatch and implant into the uterine wall.

Recurrent miscarriages; to improve implantation rate in women with previously unsuccessful IVF attempts; advanced age

Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access