Chapter 39 Care in the third stage of labour

At the end of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

Introduction

Traditionally, this period of childbirth has been regarded as ‘hazardous’ because of the risk of excessive bleeding; haemorrhage is a major cause of maternal death in the world (Khan et al 2006). However, currently within the UK, a very small number of women die as a result of excessive bleeding (Lewis 2007). This low rate of haemorrhage has been attributed to the prophylactic or routine use of active management during the third stage of labour for all women.

Active management is a package of care which includes the administration of an oxytocic drug, early clamping and cutting of the cord, and the speedy delivery of the placenta, usually by controlled cord traction (NICE 2007).

While the benefits of active management cannot be questioned for women at risk of postpartum haemorrhage, its indiscriminate use for women at low risk experiencing normal birth has been challenged (Harris 2001, Soltani 2008). Active management is not without risk and the component of active management which reduces blood loss has still not been clearly identified. A more targeted approach for active management has therefore been suggested, rather than its indiscriminate use for all women (Harris 2001, Soltani 2008), as currently there is insufficient evidence to support a clear recommendation.

The role of the midwife during the third stage of labour is:

Some midwives struggle in offering women this choice for a variety of reasons.

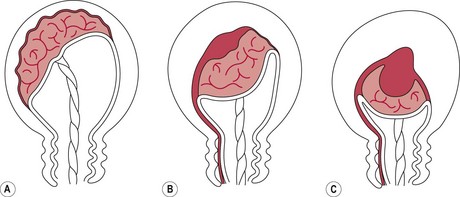

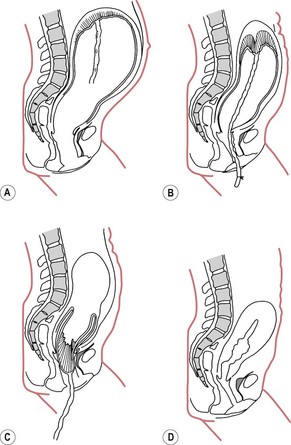

Physiology of the third stage

Separation of the placenta usually begins with the contraction that delivers the baby’s trunk and is completed with the next one or two contractions. As the body of the baby is delivered, there is a marked reduction in the size of the uterus because of the powerful contraction and retraction which take place. The placental site therefore greatly diminishes in size. Initially, placental separation was thought to be brought about by the bursting of decidual sinuses under pressure and the subsequent forming of a retroplacental blood clot which tore the septa of the spongiosa layer of the decidua basalis, detaching the placenta from the uterine wall (Brandt 1933). However, Dieckmann et al (1947) and more recently Herman et al (1993) suggest separation is caused by the active placental site uterine wall thickening and reducing in size, causing the placenta to ‘shear off’. Krapp et al (2000, 2003) describe three phases to the third stage of labour (Fig. 39.1). These three phases have now been widely accepted as describing the process of placental detachment and expulsion.

The mean length of the third stage is calculated to be approximately 6 minutes (365 ± 270 seconds) (see Fig. 39.2).

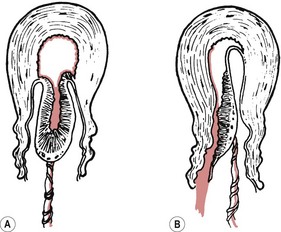

Cord clamping

If the umbilical cord remains intact during the third stage, blood can pass to and from the infant until cord pulsation has ceased. The amount of blood gained or lost by the baby will depend on its position, with the potential for a net gain of 80 mL (Yao & Lind 1974). It is suggested that if the cord is clamped early, the resulting extra fetal blood retained in the placenta prevents it from being so tightly compressed by the uterus. As a result, contraction and retraction of the uterus may be less effective, and maternal blood loss increased, leading to a greater retroplacental blood clot being formed. Botha (1968) does not consider the formation of a retroplacental blood clot a physiological process. Rather, it occurs as a result of this intervention. Late cord clamping has also been associated with benefits for the infant (Hutton & Hassan 2007) (Box 39.1).

Presentation of the placenta at the vulva

During the expulsive phase, the placenta may appear at the vagina in one of two ways (Fig. 39.3).

Schultze

The placenta appears fetal surface first, like an inverted umbrella with the membranes trailing behind. Any blood lost during the third stage will collect on the maternal surface of the placenta and be encased by the membranes. Over 80% of placentae are delivered in this way (Akiyama et al 1981).

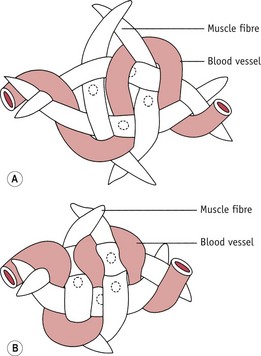

Control of bleeding

Any factor that interferes with the normal physiological processes can influence the outcome of the third stage of labour (see Box 39.2). This includes a variety of complications of pregnancy and childbirth as well as the actions of individual midwives. Oxytocic drugs given prior to and during the third stage of labour also influence events. A woman’s ability to avoid complications will also be based on her general health and by avoiding predisposing factors, such as anaemia, ketosis, exhaustion, and hypotonic uterine action.

Management of the third stage of labour

Commonly, midwives describe two ways of managing the third stage: active management and expectant management. However, difficulties remain in defining what these terms mean, as midwives practise both methods in a variety of different ways (Harris 2005). The most commonly described form of each management will be outlined here with discussion about where variation may take place. The woman and her midwife will have discussed options for the third stage during the antenatal period and again during labour and made a decision over which management she would like.

Expectant management

Principles of expectant management

Positioning the baby after birth

Whichever position a woman chooses to give birth in, the newborn infant will be placed either on the bed/floor covering between the woman’s legs or on the woman’s abdomen, depending on her choice. Early skin-to-skin contact is advantageous in maintaining the infant’s temperature, in promoting successful breastfeeding and in supporting development of mother–infant attachment (Moore et al 2007). The midwife then steps back to leave the woman and her family to experience undisturbed the powerful first meeting with their new baby, while continuing to observe the wellbeing of the infant and maternal vaginal blood loss.

When to cut the cord

There is some debate about when the umbilical cord should be clamped and cut. The potential benefits and risks to the mother and infant of delayed cord clamping (McDonald & Middleton 2008) are being considered alongside the routine use of active management which normally incorporates immediate clamping and cutting of the cord (NICE 2007, WHO 2007). In accordance with the principles of non-intervention in expectant management, Inch (1985) suggests that ideally the cord should be left intact until the placenta and membranes are completely expelled, as this enables compaction and compression of the placenta and retraction of muscle fibres to occur unhindered. There may also be beneficial effects of continued delivery of oxygenated blood to the newborn infant via the cord (Hutchon 2006), particularly in those born prematurely or asphyxiated. In a study of premature infants conducted by Kinmond et al (1993), a 30-second delay in cord clamping with the infant held 20 cm below the introitus was associated with improved outcome for the baby. A more recent study in term neonates has linked a delay in cord clamping of 2 minutes with significantly higher mean corpuscular volume, ferritin and total body iron stores in the infant up to 6 months of age (Chaparro et al 2006). Early cord clamping has also been associated with fetomaternal transfusion, of particular importance in women who are rhesus negative (Lapido 1972). Enkin et al (2000) suggest that free bleeding of the cut end of the severed umbilical cord reduces the risk of fetomaternal transfusion. Placental cord drainage has also been associated with a reduction in the length of the third stage of labour (Soltani et al 2005).