Chapter 37 Care in the second stage of labour

After reading this chapter, you will:

Introduction

The anatomical second stage of labour has been traditionally defined as the period from full dilatation of the os uteri to the birth of the baby. However, women do not experience labour and birth by its anatomical divisions, or by the dilatation of the cervix (Gross et al 2006), and labours do not usually progress at a uniform rate.

The distinctive physiological changes that occur just before or around the time the cervical os is fully dilated are traditionally defined as ‘transition’. There is a paucity of formal evidence about the nature of transition, although some observational studies have been undertaken (Crawford 1983, Roberts & Hanson 2007). During or following this phase, the woman begins to feel a variable urge to bear down. Anecdotal evidence indicates that it is not uncommon for midwives to offer women pharmacological pain relief if the urge to bear down occurs when vaginal examination indicates that the anatomical second stage is still some way off. If she then progresses more quickly than expected, such pain relief may inhibit the natural urge to bear down actively. It is thus essential that midwives know how to recognize the transitional phase of labour, and how to support women effectively at this time.

Signs of progress

Transition

If a vaginal examination is undertaken, the mother’s cervical os will typically be found to be between 7 and 9 cm dilated, though smaller dilations have been reported (Downe et al 2008). There have been occasional reports of transition (evidenced by an early pushing urge) occurring when the cervical os is less than 7 cm dilated (Roberts et al 1987).

Reflective activity 37.1

Expulsive phase

Some midwives have noted the appearance of a rounded area at the level of the lower back, the so-called rhombus of Michaelis (Sutton & Scott 1996). Sutton & Scott note that it is caused by ‘the pressure of the fetal head [which] … lifts the sacrum and the coccyx out of the way’. They also observe that the woman’s instinctive reaction to the descent of the fetus is to arch her back, push her buttocks out (or off the bed if she is semi-recumbent) and throw her arms back to grasp onto any fixed object behind her. They hypothesize that this is a physiological response, since it causes a lengthening and straightening of the curve of Carus, optimizing the fetal passage through the birth canal.

Physiology of the second stage of labour

Secondary powers

The expulsion of the fetus is further aided by the voluntary muscles of the diaphragm and abdominal wall. As the presenting part descends to approximately 1 cm above the level of the ischial spines, pressure from the fetal presentation stimulates nerve receptors in the pelvic floor, and the woman experiences the desire to bear down. This is termed the ‘Ferguson reflex’ (Ferguson 1941). This sensation may occur prior to the end of the anatomical first stage of labour, or at cervical full dilatation. The voluntary muscles of the chest and abdominal wall act reflexively in concert with the uterine contractions to overcome the resistance of the vagina, pelvic floor muscles, and external parts. During this process, the diaphragm is lowered and the abdominal muscles contract.

Mechanism of labour

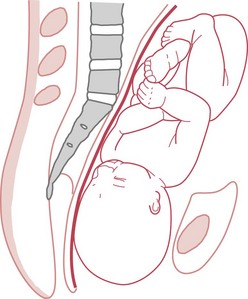

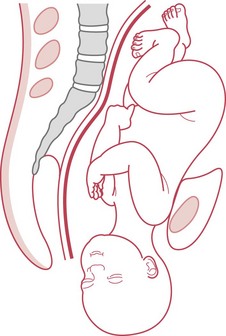

Descent

Descent is the process whereby the fetal head moves into the pelvis (Fig. 37.1). Engagement occurs when the widest diameter of the presenting part enters the pelvis. This is more likely to occur prior to the onset of labour in nulliparous women.

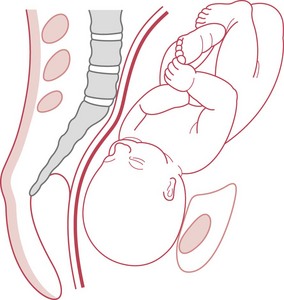

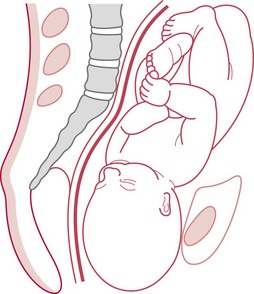

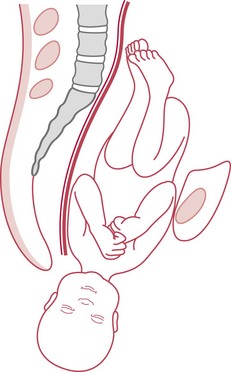

Internal rotation

When the occiput meets the resistance of the pelvic floor, it rotates forward 45° (Fig. 37.2). The slope of the pelvic floor aids this internal rotation forwards, allowing the head to emerge in the longest diameter of the pelvic outlet; that is, the anteroposterior diameter (Figs 37.3 and 37.4). The occiput then escapes under the pubic arch and the head is crowned.

Crowning of the head

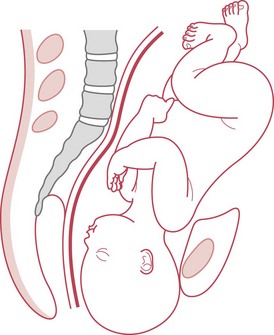

The head is crowned when it has emerged under the pubic arch and no longer recedes between contractions. The widest transverse diameter of the head (the biparietal diameter) is born (Fig. 37.5).

Restitution

When the head is born, it rights itself with the shoulders (Fig. 37.6). During the movement of internal rotation, the head is slightly twisted because the shoulders do not rotate at that time. The baby’s neck is untwisted by restitution.

Internal rotation of the shoulders

The shoulders undergo an internal rotation similar to that of the head and then lie in the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet. The head, being free outside the birth canal, moves 45° at the same time, so internal rotation of the shoulders is accompanied by external rotation of the head. Rotation follows the direction of restitution; thus the occiput turns to the same side of the maternal pelvis as it was at the beginning of labour (Fig. 37.7).

Duration of the second stage of labour

In the presence of effective uterine activity, where there is progressive descent of the presenting part, and the condition of the mother and fetus does not give rise for concern, time alone does not provide sufficient grounds for curtailment of the second stage. Studies in this area demonstrate increased intervention and morbidity over time, but it is not clear if this is due to actual or anticipated pathology (Altman & Lydon-Rochelle 2006). Intervention should be based on the rate of progress and the condition of the mother and baby rather than on the time which has elapsed since full dilatation of the cervix.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree