Chapter 36 Care in the first stage of labour

Introduction

Labour and birth are an amazing integration of powerful physiological and psychological forces that bring a new human life into the world. It is difficult not to devalue labour and birth when it is analysed, dissected and examined in order to make it understood, as it works best as a coherent whole. There are key physical, emotional and social dimensions to the process of labour, in that the arrival of a baby heralds the birth or extension of a family. Throughout history, labour and birth had special meaning for every culture and their occurrence is often marked by spiritual and cultural symbols (Kitzinger 2000). In the UK today, such rituals have been marginalized by the medical environment in which most parturition takes place, with about 95% of births occurring in consultant units, 2.5% at home (Richardson & Mmata 2007) and 2.5% in free-standing midwifery-led units (Walsh 2007a). For the midwife, a holistic understanding of labour and birth requires an awareness of the physiological/psychological changes and ability to see these remarkable events as deeply social and even political. This perspective has, as a starting point, a profound respect for and trust in women’s innate ability to birth without technology or medical intervention. The chapter will attempt to describe the changes, the events and the care from these philosophical positions.

Two birth stories (Case scenarios 36.1 and 36.2) reveal the complexity of labour and birth.

Other aspects are key to assisting our understanding of these births. Both babies were born at home. Both women had people in attendance whom they knew and had chosen to be there. Neither woman had any drugs, nor common birth interventions. They did it ‘naturally’. Their births were not typical of 21st-century childbirth experience in the UK. More typically, childbirth occurs in hospital with carers who have not been previously met, using routine interventions including continuous electronic fetal monitoring. One in three results in an instrumental vaginal delivery or a caesarean section (Richardson & Mmata 2007). It could be argued that normal labour and birth is under threat, with only about 47% of women in England having a drug-free normal birth (Richardson & Mmata 2007).

The continuum of labour

An alternative approach is beginning to gain exposure through the writings of midwives like Downe & McCourt (2008), where labour is a continuum from onset to completion, characterized by particular physiological and psychological behaviours at various points on that continuum. Some of these behaviours are anatomical changes, for example, changes in the cervix; some are physiological, such as release of body hormones; and some psychological, such as an alertness and focusing just prior to birth.

If the midwife anticipates a normal outcome to labour and birth, and trusts the woman’s physiology will function optimally, this can impact positively on the woman’s own attitude. Women with an optimistic demeanour towards childbirth have better experiences and outcomes than those beset by anxiety and fear of what could go wrong (Green et al 1998). Midwives play a key role in empowering women as they approach childbirth.

Characteristics of labour

Normal labour naturally follows a sequential pattern that involves painful regular uterine contractions stimulating progressive effacement and dilatation of the cervix with descent of the fetus through the pelvis, culminating in the spontaneous vaginal birth of the baby, followed by the expulsion of the placenta and membranes. This traditional and orthodox biomedical definition of normal labour divides labour into three stages, and designates maximum time frames, depending on a woman’s parity, as shown in Table 36.1:

Table 36.1 Approximate time taken for each stage of labour

| Primigravidae | Multigravidae | |

|---|---|---|

| First stage | 12–14 hours | 6–10 hours |

| Second stage | 60 minutes | Up to 30 minutes |

| Third stage | 20–30 minutes, or 5–15 minutes with active management | 20–30 minutes, or 5–15 minutes with active management |

The social model is more holistic and has contrasting values to the biomedical model (Table 36.2).

Table 36.2 Medical and social model

| Medical model | V | Social model |

|---|---|---|

| Body as machine | Whole person | |

| Reductionism – powers, passages, passenger | Integrate – physiology, psychosocial, spiritual | |

| Control and subjugate | Respect and empower | |

| Expertise/objective | Relational/subjective | |

| Environment peripheral | Environment central | |

| Anticipate pathology | Anticipate normality | |

| Technology as master | Technology as servant | |

| Homogenization | Celebrate difference | |

| Evidence | Intuition | |

| Safety | Self-actualization |

The alternative values of the social model mean that the strenuous work of labour is acknowledged as fundamental. Gould (2000) acknowledged this along with the crucial role of movement. This highlights the courage and perseverance demonstrated by women as they ‘work’ during labour and the importance of an environment where movement will be facilitated.

Physiology of labour

Several physiological factors integrate as labour develops (Box 36.1), and these will be examined in turn.

Box 36.1

Summary of the physiological changes in the first stage of labour

Cervical effacement and dilatation

These occur as a result of contraction and retraction of the uterine muscle.

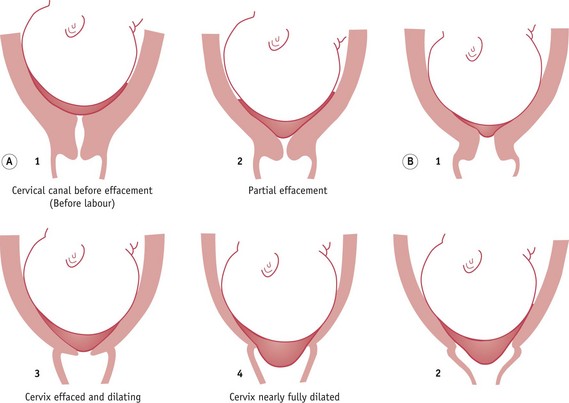

Effacement (taking up) of the cervix may start in the latter 2 or 3 weeks of pregnancy and occurs as a result of changes in the solubility of collagen present in cervical tissue. This is influenced by alterations in hormone activity, particularly oestradiol, progesterone, relaxin, prostacyclin and prostaglandins (Blackburn 2007). Braxton Hicks contractions, which become stronger in the final weeks of pregnancy, may also enhance the process. Effacement is completed in labour, the cervix becomes shorter and dilates slightly, becoming funnel shaped as the internal os opens to form part of the lower uterine segment (see Fig. 36.1).

Progressive dilatation of the cervix (see Fig. 36.2) is a definitive sign of labour.

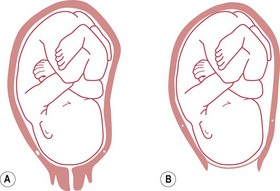

In primigravidae, effacement of the cervix usually precedes dilatation; however, in multigravidae, effacement and dilatation of the cervix normally occur simultaneously (see Fig. 36.2).

Coordination of contractions

The coordinated uterine activity characteristic of normal labour occurs as a result of near-simultaneous contraction of all myometrial cells. During pregnancy, increasing numbers of gap junctions form between the cells of the myometrium. These low-resistance communication channels enhance electrical conduction velocity and facilitate the coordination of myometrial contraction (Blackburn 2007).

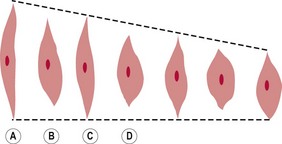

Retraction

Retraction is a state of permanent shortening of the muscle fibres and occurs with each contraction (see Fig. 36.3).

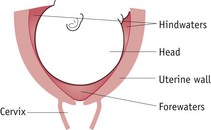

Rupture of the membranes

The membranes are thought to rupture as a result of increased production of prostaglandin E2 in the amnion in labour (McCoshen et al 1990) and the force of the uterine contractions, causing an increase in the fluid pressure inside the forewaters and a lessening of the support as the cervix dilates. In normal labour the membranes usually rupture during the second stage of labour.

Show

There is increasingly awareness of the relationship between oxytocin release and the level of catecholamines (see Ch. 35). Anxiety and fear stimulate the release of adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and inhibit oxytocin; hence the importance of birth environment and birth relationships in promoting calm and confidence in birthing women.

Care during the first stage of labour

Now that deaths in childbirth for women and babies in the western world are rare, women’s experience of childbirth has taken on greater significance and has become a major focus for the professionals assisting childbirth. Most early research on labour and birth did not explore women’s experiences and was based around professionals’ priorities and their interests. Recent studies have determined women’s views on various aspects of care (Lally et al 2008, Redshaw et al 2007, Rudman et al 2007) and these can be summarized under the following themes:

These themes should underpin the philosophy of care and its application, helping to define woman-centred care, as described and endorsed in maternity care policy at government level (DH 2007a, 2007b).

In order to provide woman-centred care, the midwife should:

Partnership in care

The relationship between the woman and her midwife is ideally a partnership (Pairman 2000) which should begin in pregnancy, and has been described as ‘skilled companionship’ or the ‘professional friend’ in its intimacy and reciprocity (Page 1995). The partnership ethos requires a social rather than medical model of maternity care, endorsing the involvement of the woman and her partner in decision-making, and requiring the woman to be able to voice her needs and wishes freely. The midwife should strive to build a relationship of mutual trust and create an environment in which expectations, wishes, fears and anxieties can be readily discussed. This requires good communication, which results from a two-way interaction between equals.

Emotional and psychological care

Throughout labour there should be a free flow of information between the woman, her partner and the midwife, particularly in relation to examinations and their findings. Being fully informed and involved in decision-making helps the woman to retain a sense of autonomy and control (Healthcare Commission 2008). The midwife should be aware that not all individuals may feel sufficiently secure or freely able to express fears or anxieties during labour. Circumstances such as an unwanted pregnancy, fear or previously poor relationships with professional caregivers may engender feelings of unhappiness, hostility and resentment. The midwife needs to be particularly sensitive to non-verbal indicators of such feelings and give the necessary help and support needed by the woman.

The role of the birth supporter

Evidence from a number of studies indicates the positive effect of continuous support in labour (Hodnett et al 2008a). Although it is usual in the UK for a couple to support each other in labour, some women may choose to have a relative, friend, or labour supporter from a voluntary organization, such as the National Childbirth Trust (NCT), as labour companions. Whoever has been chosen, the midwife should explore with supporters their experiences of childbirth, their role expectations during labour and their ability to undertake the supporter role. It has been suggested that if chosen supporters have had negative childbirth experiences, these need to be addressed by the midwife if they are not to hinder the supporting relationship with the woman.

Advocacy

For some women, fear of the unknown, being cared for in hospital by unfamiliar people, greater pain than expected or the effect of analgesic drugs can cause feelings of vulnerability, loss of personal identity, and powerlessness. This may be magnified for women for whom English is not their first language. Vulnerable individuals can lose the ability to adequately express their needs, wishes, values and choices and adopt a passive recipient role. The midwife may need to act as advocate, in order to ensure that personal needs are met (Walsh 2007b). This includes informing, supporting and protecting women, acting as intermediary between them and obstetric and other professional colleagues, and facilitating informed choice. In order to achieve this, the midwife must be professionally confident, have a clear awareness of the woman’s needs, and be able to communicate these to other colleagues to ensure effective collaboration. Developing and trusting intuition is central to this activity. The midwife’s rapport and connectedness with the woman for whom she is caring mean that appropriate decision-making and a facilitatory birth environment is more likely (Walsh 2007a). Using these skills, the midwife is more able to empower the woman and her partner so that they feel sufficiently informed and confident to participate in decision-making during this important life experience.

Birth environment

Home

Home birth has long generated an intense debate, and birth at home has become a rallying point for midwives and women who endorse childbirth’s essential normality against those who can only view its normality retrospectively. Tew (1998) first challenged the dominant 1970’s/1980’s view that the safest environment for birth was hospital. She exposed the fundamental flaw of assigning a single cause (hospitalization of birth) to a discrete effect (lowering perinatal mortality rates) without consideration of alternative explanations. This spurious logic had led to a nationwide movement of birth to hospitals over 20 years before an alternative explanation gained credibility – that the fall was due to the dramatic improvement in the general health of women in the post-war period coupled with an even more dramatic rise in living standards (Campbell & McFarlane 1994, Tew 1998).

It is now acknowledged that current evidence does not provide justification for requiring that all women give birth in hospital (Olsen & Jewell 2006) and that women should be offered an explicit choice when they become pregnant of where they want to have their baby (DH 2007a). A comprehensive literature review of home birth research, which included 26 studies from many parts of the developed world, concluded that ‘studies demonstrate remarkably consistency in the generally favourable results of maternal and neonatal outcomes, both over time and among diverse population groups’ (Fullerton & Young 2007:323). The outcomes were also favourable when viewed in comparison to various reference groups (birth-centre births, planned hospital births).

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated clear benefit in a number of associated elements of the home birth ‘package of care’, including continuity of care during labour and birth (Hodnett et al 2008) and midwife-led care (Hatem et al 2008), both of which are probably universal aspects of home birth provision.

Though official UK government policy up to the present is to offer women a choice about place of birth, the UK home birth rate remains just above 2%, compared with 25% in the early 1960s (Chamberlain et al 1997). There are anecdotal stories of women either being discouraged from choosing the home birth option or being told that staff shortages may impact on the availability of midwives.

Birth centres or midwifery-led units

Free-standing birth centres as an option for women are especially relevant now (see Chs 32 & 34). Maternity services across the UK are merging, driven by the growth of neonatal tertiary referral centres and by rationalizing of management and clinical structures of individual hospitals that are no longer seen as cost-effective if they remain separate. These pressures are leading to stakeholders choosing to combine birth facilities on one site with neonatal services or retain present infrastructures and open midwifery-led units or birthing units (DH 2007b). The current trend appears to favour the first option, potentially resulting in further centralization of birth, in some areas up to 10,000 births per year in a single hospital, mirroring the controversial process in the 1980s, during which many small hospitals and isolated GP units closed, since lamented by midwives and user lobby groups.

Research and evaluation is needed to establish whether expansion is appropriate, as currently, service providers and clinicians are drawing from a pool of methodologically flawed papers. There are currently no RCTs and a paucity of good-quality research on free-standing birth centres or midwifery-led units. A structured review found these environments lowered childbirth interventions but methodological weaknesses in all studies made conclusions tentative (Walsh & Downe 2004), findings echoed by Stewart et al’s (2005) commissioned review. This model, endorsed by the Department of Health in England, reflects policy thinking that free-standing birth centres would be unlikely to have worse outcomes than home birth (DH 2007a).

Evaluations of integrated birth centres or alongside midwifery-led units have shown no statistical difference in perinatal mortality, suggesting encouraging results for the reduction in some labour interventions (Hodnett et al 2010). Debate continues regarding the noted non-significant trend in some of the studies of higher perinatal mortality for first-time mothers (Fahy 2005, Tracey et al 2007). This is unlikely to be resolved until contextual studies exploring the interface at transfer or impact of contrasting philosophies is examined in depth.

Qualitative literature on home birth and free-standing birth centres highlights two other aspects of care: how temporality is enacted and how smallness of scale impacts on the ethos and ambience of care. The regulatory effect of clock time is less evident both at home and in birth centres. Labour rhythms rather than labour progress tend to be emphasized by staff and there is usually greater flexibility with the application of the labour record, the partogram (Fig. 36.5). Part of the reason for this lies in the absence of an organizational imperative to ‘get women through the system’ (Walsh 2006a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree