Chapter 61 Procedures in obstetrics

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

A baby may enter the world spontaneously through the mother’s vagina, with only the occasional need for guidance from attendants, by operative means with the use of forceps, vacuum extraction, or by caesarean section. Yet rates for normal birth have seemingly fallen over the previous two decades. The Healthcare Commission review of the maternity services (Healthcare Commission 2008) revealed normal birth rates in maternity units are as low as between 32% and 40%. Whilst there are some areas where home births are increasing and despite admirable drives by a small number of celebrities, many midwives and various pressure groups, instrumental delivery rates continue to increase annually along with caesarean sections. It might be considered that, soon, spontaneous vaginal delivery will no longer be the accepted normal route.

Operative vaginal deliveries

Forceps and ventouse extraction have the potential to safely remove the infant and mother from a hazardous situation (Dennen & Hayashi 2005), and even to save lives. Taking this into consideration, however, the increase in their use has an impact on the health of women and their babies. Highest rates of trauma are consistently observed with operative procedures, with short-term and long-term morbidity.

Neonatal complications

After any instrumental vaginal delivery, the baby may suffer hypoxia, have lower Apgar scores and require appropriate resuscitation. Facial or scalp abrasions or bruising are common. A cephalhaematoma may develop because of friction between the fetal head and pelvis or forceps blade, as well as from the suction of the ventouse cup. There may be an increase in jaundice due to reabsorption of haemoglobin associated with this bruising (Dennen & Hayashi 2005). Facial palsy, which is usually temporary, may occur owing to the compression of the facial nerve which runs anteriorly to the ear, by the forceps blade. Intracranial trauma and haemorrhage is higher amongst infants delivered by vacuum extraction, forceps or caesarean section (Towner et al 1999). In more rare circumstances, tentorial tears and rupture of the great vein of Galen may occur, leading to bleeding and compression of the brainstem. Skull fractures are usually linear but occasionally a depressed fracture can result in a subarachnoid haemorrhage. Kielland’s forceps can cause unexplained convulsions. Retinal haemorrhages are more common in vacuum extraction deliveries (Vacca 1996). The most serious complication to occur is that of subgaleal haemorrhage.

Maternal complications

The most common injuries to the genital tract are cervical, vaginal and perineal tears, haematomas and rectal lacerations (see Ch. 40). Bladder or urethral injury may occur, causing urinary retention and even the formation of a fistula. Perineal pain due to bruising, oedema, trauma and episiotomy can impair sexual function and infant feeding. Pelvic floor disorders and long-term pelvic floor morbidity are strongly associated with instrumental delivery (Bahl et al 2005). There is an increased risk of haemorrhage (Walsh 2000). A rare complication is that the cervix and lower segment of the uterus may be damaged.

The psychological effects of instrumental delivery may include fear and anxiety in relation to subsequent pregnancy, and feelings of failure, inadequacy and disappointment. Both forceps and ventouse-assisted deliveries were found to be predictive factors of acute trauma symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of women’s birth experiences (Creedy et al 2000). Jolly et al (1999) concluded that caesarean section and vaginal instrumental birth are associated with voluntary and involuntary infertility as many mothers may be left with fearful feelings about future childbirth: 13% more of women who had a caesarean section and 6% more of those who had instrumental births had not had a second child compared with those following normal birth.

Key aspects of midwifery practice

Policies

Blanket policies to treat prolonged labour and ‘failure to progress’ should be examined as there is much literature available to explore long-held beliefs of the definition of the duration and progress of labour. Even in 1973, when medicalization was really taking control of childbirth, Studd (1973) questioned the arbitrary application of time limits on labour considering the confusion over the diagnosis of the onset of active labour. Yet this confusion remains and time limits for stages of labour remain in place.

Position for labour and delivery

An upright position, preferably mobile, assists the woman to feel in control, can reduce her distress and help her to adopt comfortable positions more easily. During a review of trials for The Cochrane Library, Gupta & Nikoderm (2001) highlighted that adopting upright positions in labour appeared to reduce the number of assisted deliveries and fewer abnormal fetal heart rate patterns were noted (see Chs 36 and 37).

Diet, fasting and nutrition

Fasting women throughout a normal labour can add to exhaustion, as labour is a time of great energy demand and it is estimated that a labouring woman may require 800–1100 kcal/hour (Ludka & Roberts 1993). Whilst women adapt to a small rise of ketones in labour, blood pH can be reduced in starving women and result in ketoacidosis. Even as far back as the 1960s, Mark (1961) discovered that uterine activity was influenced by environmental pH and that myometrial cells spontaneously contract with increased alkalinity, preferably between 7.8 and 7.1. Ketones that build up may also cross the placenta, and if there is an accumulation in the fetus, this can affect fetal wellbeing and fetal activity (Swift 1991).

Supportive presence during labour

A Cochrane review highlights that the presence of an appropriate support person throughout labour is associated with a decreased incidence of epidural anaesthesia, dystocia and instrumental deliveries (Hodnett 2001).

Amniotomy and Syntocinon

Amniotomy can increase the requirement for instrumental delivery and caesarean section (Johnson et al 1997). It is recognized that amniotomy causes fetal heart abnormalities owing to cord and head compression, which then increases the risk of interventions. It can inhibit the rotation of some malpositions – for example, occipitoposterior positions – which may predispose to delay. There is an increase in pain during contractions, which may, in turn, increase the demand for epidural analgesia. Syntocinon reduces the oxygen supply to the baby’s brain. The fetus may then display signs of fetal distress, increasing the need to dramatically shorten the labour (O’Regan 1998).

Indications for the use of assisted vaginal delivery

If an instrumental delivery is necessary

Procedure

Ventouse vs forceps

Debate exists over the preferred instrument for vaginal delivery once it is believed to be necessary. There are two methods for instrumental delivery: forceps and vacuum (ventouse) extraction. A Cochrane systematic review of nine randomized controlled studies involving 2849 primiparous and multiparous women compared vacuum extractions with forceps. Ventouse appears to be significantly more likely to fail at achieving a vaginal delivery, but is less likely to produce maternal trauma and less likely to be associated with severe perineal pain. However, it does produce increased rates of cephalhaematoma, retinal haemorrhages and low Apgar scores at 5 minutes. There appeared no difference in long-term outcome between the two instruments (Johanson & Menon 2000).

Forceps

Forceps were first described in 400 BC by Hippocrates to extract dead fetuses. From a birthroom scene on a marble relief, it would appear that forceps were also used in Roman times, but in modern history the use of forceps as an aid to vaginal delivery has been known only since their invention by the Chamberlen family in the 1600s (Pearson 1981). The family tried to keep the nature of their instruments a secret, as these forceps offered a practical possibility of live births from obstructed labours and were a source of fame and money to those who used them.

Since the introduction of forceps, many attempts have been made to improve the efficacy and safety of the instrument for specific obstetrical situations and the shortcomings of current forceps design is acknowledged. In fact, the blades of some designs were designed for delivery of the long ovoid moulded head, which was a common shape adapted from prolonged labour. As a result of present-day care, this shape is less frequently seen and the head is less moulded and more spherical (Hibbard 1989).

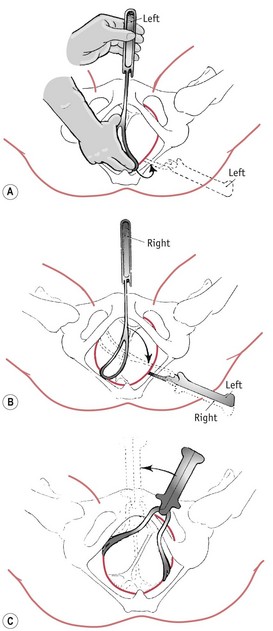

Forceps may be used in two ways: to exert traction without rotation; and to correct malposition, for example, occipitoposterior position, by rotation prior to traction. Rotation is rarely performed now owing to the trauma to the mother and the baby (Figs 61.1 and 61.2). There are definitive texts available (see website) which outline the procedures for forceps delivery, but here it would appear more pertinent to discuss certain principles for all types of the delivery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree