CHAPTER 21 1. Describe clinical manifestations of oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, and conduct disorder. 2. Discuss etiology and comorbidities of the impulse control disorders. 3. Describe biological, psychological, and environmental factors related to the development of impulse control disorders. 4. Compare your feelings about working with someone with an impulse control disorder with someone in your class. 5. Formulate three nursing diagnoses for impulse control disorders, identifying patient outcomes and interventions for each. 6. Identify evidence-based treatments for oppositional defiant, intermittent explosive, and conduct disorders. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis The disorders presented in this chapter were previously grouped with other disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. While the problems presented here have their origins early in life, they may not be diagnosed until the person is an adult. According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), major disorders considered under this umbrella include the following: The person with this disorder also shows a pattern of deliberately annoying people and blaming others for his or her mistakes or misbehavior. This child may frequently be heard to say “He made me do it!” or “It’s not my fault!”. Certain aspects of the disorder are seen more in boys than girls. For example, boys are more likely to annoy and blame others, and girls argue more. Additionally, clinicians may view and judge an individual’s display of behavior differently depending on their gender. For example, it may be more socially appropriate in many cultures for a boy to express aggression then a girl (de Ancos & Ascaso, 2011). Left untreated, some children outgrow this disorder; however, most do not and continue to experience social difficulties, conflicts with authority figures, and academic problems that impact their whole lives (Gale, 2011). Oppositional defiant disorder is often predictive of emotional disorders in young adulthood (Rowe et al., 2010). Anything can trigger the inappropriate aggression reaction to the situation. An example may be a person punching his fist through a pane of glass after not being able to locate his favorite video game. He may destroy his room, break furniture, or damage costly properly. As the rage continues, he may attack anyone who intervenes and often causes injury. The explosive anger may occur during a competitive sport, such as lashing out at opposing baseball fans when his team loses. The behavior needs to show a repetitive pattern and interference with normal functioning, such as a person being unable to stay employed because they scream and curse at their boss when given any negative feedback (Tamam et al., 2011). This disorder can impede on a person’s functioning by leading to problems with interpersonal relationships and occupational difficulties and can lead to criminal problems as well. Additionally, significant problems with physical health, such as hypertension and diabetes, have been linked to this disease (McCloskey et al., 2010). Being in a heightened state of stress and agitation for a prolonged period of time may be the correlation. It is one of the most frequently diagnosed disorders of childhood and adolescence. The people affected by this disorder may have a normal intelligence, but they tend to skip class or disrupt school so much that they fall behind and may be expelled or drop out. Complications associated with conduct disorder include academic failure, school suspensions and dropouts, juvenile delinquency, drug and alcohol abuse and dependency, and juvenile court involvement (Harvard Medical School, 2011). People with conduct disorder crave excitement and do not worry as much about consequences as others do. Childhood-onset conduct disorder occurs prior to age 10 years and is found mainly in males who are physically aggressive, have poor peer relationships, show little concern for others, and lack feelings of guilt or remorse. These children frequently misperceive others’ intentions as hostile and believe their aggressive responses are justified. Violent children also often display antisocial reasoning, such as “he deserved it,” when rationalizing aggressive behaviors (Farrell et al., 2008). Children with childhood-onset conduct disorder attempt to project a strong image, but they actually have a low self-esteem. Limited frustration tolerance, irritability, and temper outbursts are hallmarks of this disorder. Individuals with childhood-onset conduct disorder are more likely to have problems that persist through adolescence, and without intensive treatment they may later develop antisocial personality disorder as adults. There is a subset of people with conduct disorder who are also referred to as being callous and unemotional. Callousness is characterized by a lack of empathy, such as disregarding and being unconcerned about the feelings of others, having a lack of remorse or guilt except when facing punishment, and being unconcerned about meeting school and family obligations; unemotional traits include a shallow, unexpressive, and superficial affect (Stellwagen & Kerig, 2010). Callousness may be a predictor of future antisocial personality disorder in adults (Burke et al., 2010). Two problems are related to impulse control disorders and are worthy of mention in this chapter. They are pyromania and kleptomania. Pyromania is described as repeated deliberate fire setting. The person experiences tension or becomes excited before setting a fire and shows a fascination with or unusual interest in fire and its contexts such as matches. The person also experiences pleasure or relief when setting a fire, witnessing a fire, or participating in the aftermath of a fire. The fire setting is done solely to satisfy this relief pleasure and not for other reasons, such as to conceal a crime. Like many mental illnesses, this disorder can stem from a form of maladaptive coping a person learned early in life in relation to having unmet needs and poorer social skills (Lyons et al., 2010). Kleptomania is a repeated failure to resist urges to steal objects not needed for personal use or monetary value. For example, a person may take books even though they cannot read or baby outfits they consider cute even though they have no children and have plenty of money to buy them. The person experiences a buildup of tension before taking the object, and this is followed by relief or pleasure following the theft. Some research has explored whether this disorder is more closely linked to others of addictive behavior, such as substance abuse disorder, since the person is acting to satisfy a compulsion (Talih, 2011). See Table 21-1 for a summary of the characteristics of impulse control disorders. TABLE 21-1 CHARACTERISTICS OF IMPULSE CONTROL DISORDERS Connor, D. F., Ford, J. D., Albert, D. B., & Doerfler, L. A. (2007). Conduct disorder subtype and comorbidity. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 19(3), 161–168; Kessler, R. C., Coccaro, E. F., Fava, M., Jaeger, S., Jin, R., & Walters, E. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(6), 669–78; Merikangas, K. R., He, J., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent supplement. Journal of the American Academy of Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. Oppositional defiant disorder is reported to have rates varying between 2% to 16%, depending on the population sampled and the method of measurement. Kessler and colleagues (2012) report the 12-month prevalence at 8.3% among adolescents. Intermittent explosive disorder may affect an alarming number of people—up to 16 million Americans, or about 7% of all adults—in their lifetimes (National Institute of Mental Health, 2006). Conduct disorder prevalence has been on the rise and may be higher in urban settings as compared to rural areas. Rates vary widely from 1% to over 10% based on the population sampled. As previously stated, conduct disorder is one of the most frequently diagnosed disorder in children and adolescents and has an estimated rate of 5.4% in both inpatient and outpatient mental health facilities (Kessler et al., 2012). Oppositional defiant disorder is related to a variety of other problems, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, suicide, bipolar disorder, and substance abuse (Fitzgibbons, 2011). There has long been a theory that disorders within this category are interrelated. Research supports a progression from childhood-onset oppositional defiant disorder to conduct disorder. Some experts even believe that oppositional defiant disorder is a mild form of conduct disorder. A subset of people in this group may progress to antisocial personality disorder (Burke, Waldman, & Lahey, 2010). Conduct disorders are often comorbid with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance use disorders, and learning disabilities. Children with bipolar disorder may often be confused with conduct disorder and may result in delayed detection and treatment (Kovacs & Pollock, 2009). Oppositional defiant disorder tends to occur at a young age and may be related to genetics. Many individuals diagnosed with this disorder have a family history of other mental illness. It may be that genetics produces a vulnerability or predisposition to developing oppositional defiant disorder; likewise, intermittent explosive disorder genetics appears to run in families (Coccaro, 2010). Conduct disorders are more common in children and adolescents whose parents were similarly afflicted (Mental Health America, 2012). Research demonstrates that gray matter is less dense in the left prefrontal cortex in young patients with oppositional defiant disorder (Fahim et al., 2012). This area is associated with impulse control and self-regulation. The young patients also had an increase in gray matter in the left temporal area. This area is associated with impulsivity, aggression, and antisocial personality. In boys, the structural abnormalities in brains are more pronounced—gray matter density in the orbitofrontal cortex and white matter density in the superior frontal area are reduced. Adolescents with conduct disorder have been found to have significantly reduced gray matter bilaterally in the anterior insulate cortex and the left amygdala (Sterzer et al., 2007). The insulate cortex is believed to be involved in emotion and empathy, and the amygdala also helps to process emotional reactions. Researchers believe that this reduction may be related to aggressive behavior and have found a positive correlation between this deficit and empathy scores. That is, the less gray matter in these regions of the brain, the less likely adolescents are to feel remorse for their actions or victims. Fairchild and colleagues (2011) found that regardless of age of onset gray matter reductions crucial in brain regions for processing emotional stimuli contribute to this disorder.

Impulse control disorders

Clinical picture

Oppositional defiant disorder

Intermittent explosive disorder

Conduct disorder

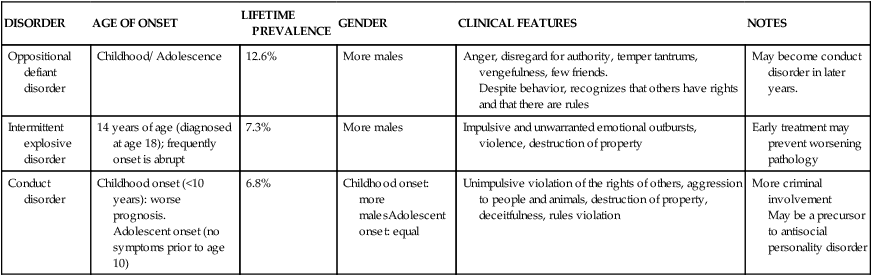

DISORDER

AGE OF ONSET

LIFETIME PREVALENCE

GENDER

CLINICAL FEATURES

NOTES

Oppositional defiant disorder

Childhood/ Adolescence

12.6%

More males

Anger, disregard for authority, temper tantrums, vengefulness, few friends.

Despite behavior, recognizes that others have rights and that there are rules

May become conduct disorder in later years.

Intermittent explosive disorder

14 years of age (diagnosed at age 18); frequently onset is abrupt

7.3%

More males

Impulsive and unwarranted emotional outbursts, violence, destruction of property

Early treatment may prevent worsening pathology

Conduct disorder

Childhood onset (<10 years): worse prognosis.

Adolescent onset (no symptoms prior to age 10)

6.8%

Childhood onset: more malesAdolescent onset: equal

Unimpulsive violation of the rights of others, aggression to people and animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness, rules violation

More criminal involvement

May be a precursor to antisocial personality disorder

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Comorbidity

Etiology

Biological factors

Genetic

Neurobiological

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Impulse control disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access