On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Define the classifications of intellectual disability. • Outline nursing interventions for the child with cognitive impairment that promote optimal development, including during hospitalization. • Identify the major biologic and cognitive characteristics of children with Down syndrome. • Outline nursing interventions for children with Down syndrome. • Identify the major characteristics associated with fragile X syndrome. • List the general classifications of hearing impairment and the effect on speech. • Outline nursing interventions for children with hearing impairment, including during hospitalization. • List the common types of visual impairments in children. • Outline nursing interventions for children with visual impairment, including during hospitalization. • Outline nursing interventions for children with retinoblastoma. • Outline nursing interventions for children with an autism spectrum disorder. Cognitive impairment (CI) is a general term that encompasses any type of mental difficulty or deficiency. In this chapter the term is used synonymously with intellectual disability and replaces the term mental retardation (MR), defined by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD, 2010). Although the needs and concerns of the family are a primary focus throughout the chapter, readers are encouraged to review Chapter 36, which details the family’s adjustment to disabilities in general. The definition of intellectual disability in children consists of three components: intellectual functioning, functional strengths and weaknesses, and age younger than 18 years at time of diagnosis. Intellectual functioning is measured by the intelligence quotient (IQ) of 70 to 75 or below. The child with an intellectual disability must demonstrate functional impairment in at least 2 of 10 different adaptive skill areas: communication, self-care, home living, social skills, leisure, health and safety, self-direction, functional academics, community use, and work (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) or have deficits in one or more adaptive domains (AAIDD, 2010). The classification system by the AAIDD allows for identification of the individual’s specific needs in four established dimensions of care (Box 37-1). Careful evaluation to identify the needs of individuals with CI is focused on promoting habilitation for each person. It is anticipated that the functional capabilities of children with CI will improve over time when support is provided. The diagnosis of CI is usually made after a period of suspicion, by professionals or the family, that the child’s developmental progress is delayed. In some cases it is confirmed at birth because of recognition of distinct syndromes such as Down syndrome and fetal alcohol syndrome. At the other extreme the diagnosis is made when problems such as speech delays arouse concern. In all cases a high index of suspicion for developmental delay and behavioral signs (Box 37-2) is necessary for early diagnosis; routine developmental screening can help in early identification (see Chapter 29). Delays are typically seen in gross and fine motor and speech development, although the latter is most predictive. Developmental delay can be described as any significant lag in a child’s physical, cognitive, behavioral, emotional, or social development when compared against developmental norms. CI is a permanent impairment encompassing cognitive ability and adaptive behavior that are functioning significantly below average (see Box 37-2). In the absence of clear-cut evidence of CI, it is more appropriate to use a diagnosis of developmental delay. A more useful approach for clinical application is classification based on educational potential or symptom severity. For educational purposes the mildly impaired group (educable MR) constitutes about 85% of all people with CI, and the group with moderate levels of CI (trainable MR) accounts for about 10% of the intellectually disabled population (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Katz and Lazcano-Ponce, 2008; Walker and Johnson, 2006) (Table 37-1). Although nurses may be familiar with the approximate range of IQ for classifying severity, they should refrain from using numbers as the criterion for assessing or evaluating the child’s abilities because numbers are of little value in counseling parents or training these children. TABLE 37-1 CLASSIFICATION OF COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT *Data from American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5), ed 5, Washington, DC, 2013, The Association; and Rittey CD: Learning difficulties: what the neurologist needs to know, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74(suppl 1):30–36, 2005. The causes of severe CI are primarily genetic, biochemical, and infectious. Although the etiology is unknown in most cases, familial, social, environmental, and organic causes may predominate. Among individuals with CI, a sizable proportion of the cases are linked to Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, or fetal alcohol syndrome. General categories of events that may lead to CI include the following (Katz and Lazcano-Ponce, 2008; Walker and Johnson, 2006): • Infection and intoxication such as congenital rubella, syphilis, maternal drug consumption (e.g., fetal alcohol syndrome), chronic lead ingestion, or kernicterus • Trauma or physical agent (i.e., injury to the brain experienced during the prenatal, perinatal, or postnatal period) • Inadequate nutrition and metabolic disorders such as phenylketonuria or congenital hypothyroidism • Gross postnatal brain disease such as neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis • Unknown prenatal influence, including cerebral and cranial malformations such as microcephaly and hydrocephalus • Chromosome abnormalities resulting from radiation, viruses, chemicals, parental age, and genetic mutations such as Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome • Gestational disorders, including prematurity, low birth weight, and postmaturity • Psychiatric disorders that have their onset during the child’s developmental period up to age 18 years such as autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) • Environmental influences, including evidence of a deprived environment associated with a history of intellectual disability among parents and siblings Nurses play a major role in identifying children with CI. In the newborn and early infancy periods few signs are present, with the exception of Down syndrome (see p. 1090). However, after this age delayed developmental milestones are the major clues to CI. In addition, nurses must have a high index of suspicion for early behavior patterns that may suggest CI (see Box 37-2). Parental concerns such as delayed development compared with siblings need to be taken seriously. All children should receive regular developmental assessment, and the nurse is often the person responsible for performing such assessments (see Chapter 29). When delays are found, the nurse must use sensitivity and discretion in revealing this finding to parents. One critical area of learning that has had a tremendous impact on education for cognitively impaired individuals is motivation. Programs based on the motivational principles of behavior modification, using positive reinforcement for specific tasks or behaviors, have demonstrated marked improvement in children’s ability to learn. Advances in technology have greatly aided in providing reinforcement, especially in children with severe disabilities and who may have physical disabilities that limit their range of capabilities. For example, with the use of specially designed switches, children are given control of some event in the environment such as turning on the television (Fig. 37-1). The television picture becomes the reinforcement for activating the switch. Repetitive use of these switches provides an early, simplistic association with a technical device that may progress to increasingly complex aids. Early-intervention program is a systematic program of therapy, exercises, and activities designed to address developmental delays in disabled children to help achieve their full potential (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Committee on Genetics, 2001; National Down Syndrome Society, 2011a; Weijerman and de Winter, 2010). Considerable evidence indicates that these programs are valuable for cognitively impaired children. Nurses working with these families need to be aware of the types of programs in their community. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990 (Public Law 101-476), states are encouraged to provide full early-intervention services and are required to provide educational opportunities for all children with disabilities from birth to 21 years of age. Services may be provided under state Programs for Children with Special Health Needs or Head Start or by private organizations such as National Down Syndrome Society,* Easter Seals,† or the Arc of the United States.‡ Parents should inquire about these programs by contacting the appropriate agencies. The child’s education should begin as soon as possible. As children grow older, their education should be directed toward vocational training that prepares them for as independent a lifestyle as possible within their scope of abilities. Teaching self-care skills also necessitates a working knowledge of the individual steps needed to master a skill. For example, before beginning a self-feeding program, the nurse performs a task analysis. After a task analysis the child is observed in a particular situation such as eating to determine what skills the child possesses and his or her developmental readiness to learn the task. Family members are included in this process because their “readiness” is as important as the child’s. Numerous self-help aids are available to facilitate independence and can help eliminate some of the difficulties of learning such as using a plate with suction cups to prevent accidental spills.§ Children who are cognitively impaired have the same needs for recreation and exercise as other children. However, because of the children’s slower development, parents may be less aware of these needs. Therefore the nurse guides parents toward selection of suitable play and exercise activities (Fig. 37-2). Because play has been discussed for children in each age-group in earlier chapters, only the exceptions are presented here. Toys are selected for their recreational and educational value. For example, a large inflatable beach ball is a good water toy; it encourages interactive play and can be used to learn motor skills such as balance, rocking, kicking, and throwing. A doll with removable clothes and different types of closures can help the child learn dressing skills. Musical toys that mimic animal sounds or respond with social phrases are excellent ways of encouraging speech. Toys should be simple in design so the child can learn to manipulate them without help. For children with severe cognitive and physical impairment, electronic switches can be used to allow them to operate toys (Fig. 37-3). Suitable activities for physical activity are based on the child’s size, coordination, physical fitness and maturity, motivation, and health (Fig. 37-4). Some children may have physical problems that prevent participation in certain sports such as atlantoaxial instability in children with Down syndrome (see p. 1090). These children often have greater success in individual and dual sports than in team sports and enjoy themselves most with children of the same developmental level. The Special Olympics* provides these children with a unique competitive opportunity. Nonverbal communication may be appropriate for some of these children, and various devices are available. For the child without associated physical disabilities a talking picture board is helpful. For children with physical limitations several adaptations or types of communication devices are available to facilitate selection of the appropriate picture or word (Fig. 37-5). Some children may be taught sign language or Blissymbols (i.e., a highly stylized system of graphic symbols representing words, ideas, and concepts). Although the symbols require education to learn their meaning, no reading skill is needed. The symbols are usually arranged on a board, and the person points or uses some type of selector to convey a message. As soon as possible parents should enroll the child in appropriate preschool programs. Not only do these programs provide education and training, but they also offer an opportunity for social experiences among the children. As children grow older, they should have peer experiences similar to those of other children, including group outings, sports, and organized activities such as scouts and Special Olympics. Nurses can assess the child’s abilities and encourage others (e.g., parents, teachers) to promote developmentally appropriate peer interaction (Johnson and Walker, 2006; National Down Syndrome Society, 2011a; Shapiro and Batshaw, 2007). These adolescents also need practical sexual information regarding anatomy, physical development, and conception.* Because of their easy persuasion and lack of judgment, they need a well-defined, concrete code of conduct. The subtleties of social sexual behavior are less beneficial than specific instructions for handling certain situations. For example, an adolescent should be told firmly never to go alone anywhere with any person that he or she does not know well. To protect him or her from abusive sexual activities, parents must observe their teenager’s activities and associates closely. The question of contraceptive protection for these adolescents is often a parental concern. Parents of these adolescents are often concerned about the advisability of marriage between two individuals with intellectual disabilities. There is no conclusive answer; each situation must be judged individually. In some instances marriage is possible, but parenthood may not be desirable because of the complexity of childrearing and the potential problem of perpetuating mental deficiency. The nurse should discuss this topic with parents and with the prospective couple, stressing suitable living accommodations and contraceptive methods to prevent pregnancy. If children are conceived, these parents require specialized help to learn to meet the needs of their offspring (Johnson and Walker, 2006). When the child is admitted, a detailed history is taken (see Chapter 29), especially in terms of all self-care activity. During the interview the child’s developmental age is assessed. It is best to avoid asking directly about IQ levels because this may make the parents uncomfortable and often tells little about the child’s actual abilities. Questions are approached positively. For example, rather than asking, “Is your child toilet trained yet?” the nurse may state, “Tell me about your child’s toileting habits.” The assessment should also focus on any special devices the child uses, effective measures of limit setting, unusual or favorite routines, and any behaviors that may require intervention. If the parent states that the child engages in self-injurious activities (e.g., head banging, self-biting), the nurse should inquire about events that precipitate them and techniques (e.g., distraction, medication) that the parents use to manage them (Johnson and Walker, 2006; Oliver and Richards, 2010). Besides having a responsibility to families with a child with CI, nurses also need to be involved in programs aimed at preventing CI. Many of the familial, social, and environmental factors known to cause mild impairment are preventable. Counseling and education can reduce or eliminate such factors (e.g., poor nutrition, cigarette smoking, chemical abuse), which increase the risk of prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction. Interventions are directed toward improving maternal health by educating women regarding the dangers of chemicals, including prenatal alcohol exposure, which affects organogenesis; craniofacial development; and cognitive ability (Defendi, 2010; Wilton and Plane, 2006). Other preventive strategies that play an important role include adequate prenatal care; optimal medical care of high-risk newborns; rubella immunization; genetic counseling and prenatal screening, especially in terms of Down or fragile X syndrome; use of folic acid supplements to prevent neural tube defects during pregnancy and the childbearing years; newborn screening for treatable inborn errors of metabolism such as congenital hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, and galactosemia; and early appropriate therapies and rehabilitation services for children with developmental disabilities. Down syndrome is the most common chromosome abnormality of a generalized syndrome, occurring in one in 691 to 1000 live births (National Down Syndrome Society, 2011b; Weijerman and de Winter, 2010). It occurs in people of all races and economic levels. The cause of Down syndrome is not known, but evidence from cytogenetic and epidemiologic studies supports the concept of multiple causality. Approximately 95% of all cases of Down syndrome are attributable to an extra chromosome 21 (group G); thus the name nonfamilial trisomy 21 (National Down Syndrome Society, 2011b; Walker and Johnson, 2006). Although children with trisomy 21 are born to parents of all ages, there is a statistically greater risk in older women, particularly those older than 35 years of age. For example, in women 35 years of age the chance of conceiving a child with Down syndrome is about 1 in 350 live births, but in women age 40 it is approximately 1 in 100. However, the majority (≈80%) of infants with Down syndrome are born to women younger than 35 years of age because younger women have higher fertility rates (National Down Syndrome Society, 2011b). Approximately 3% to 4% of the cases may be caused by translocation of chromosomes 15 and 21 or 22. This type of genetic aberration is usually hereditary and is not associated with advanced parental age. of affected people, 1% to 2% demonstrate mosaicism, which refers to a mixture of normal and abnormal cell types. The degree of cognitive and physical impairment is related to the percentage of cells with the abnormal chromosome makeup. Down syndrome can usually be diagnosed by the clinical manifestations alone (Box 37-3 and Fig. 37-6), but a chromosome analysis should be done to confirm the genetic abnormality. Life expectancy for those with Down syndrome has improved in recent years but remains lower than for the general population. More than 80% survive to age 60 years and beyond (National Down Syndrome Society, 2011b; Weijerman and de Winter, 2010). As the prognosis continues to improve for these individuals, it will be important to provide for their long-term health care and social and leisure needs. Because of the unique physical characteristics, infants with Down syndrome are usually diagnosed at birth, and parents should be informed of the diagnosis at this time. Parents usually prefer that both of them be present during the informing interview so they can support one another emotionally. They appreciate receiving reading material about the syndrome* and being referred to others such as parent groups or professional counseling for help or advice. After parents are aware of the diagnosis, they are confronted with the crisis of losing their perfect or dream child and grieving for and accepting their reality child. Consequently the parents’ responses to the child may greatly influence decisions regarding future care. Some families willingly take the child home, whereas others consider immediate residential placement. The nurse must carefully answer questions regarding developmental potential. Institutionalization is no longer an option. For families unable or ill prepared to choose taking the newborn home, specialized foster care and adoption are other options (see Critical Thinking Case Study). Dietary intake needs supervision. Decreased muscle tone affects gastric motility, predisposing the child to constipation. Dietary measures such as increased fiber and fluid promote evacuation. The child’s eating habits may need careful scrutiny to prevent obesity. Height and weight measurements should be obtained on a serial basis, especially during infancy. Because these children grow more slowly than the general pediatric population, special growth charts developed for them should be used (AAP, Committee on Genetics, 2001; National Down Syndrome Society, 2011c). Prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome is possible through chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis because chromosome analysis of fetal cells can detect the presence of trisomy or translocation. However, analysis will not identify sporadic cases in young women when there is no indication for prenatal testing. Testing for low maternal serum α-fetoprotein, high chorionic gonadotropin, low unconjugated estriol levels, maternal serum fetal cell markers, and measurement of the first-trimester nuchal transparency ultrasound marker may identify an affected fetus in women, who can then undergo amniocentesis (Bahado-Singh and Argoti, 2010; Benn and Chapman, 2009; National Down Syndrome Society, 2011b). Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause of CI and the second most common genetic cause of CI after Down syndrome. It has been described in all ethnic groups and races. The incidence of affected boys is one in 3600; the incidence of affected girls is one in 4000 to 6000; the incidence of carrier girls is one in 100 to 260; and the incidence of carrier boys is one in 250 to 800 worldwide (Hagerman, 2008; National Fragile X Foundation, 2010). The inheritance pattern has been termed X-linked dominant with reduced penetrance. This is in distinct contrast to the classic X-linked recessive pattern in which all carrier females are normal, all affected males have symptoms of the disorder, and no males are carriers. Consequently genetic counseling of affected families is more complex than that for families with a classic X-linked disorder such as hemophilia. Prenatal diagnosis of the fragile X gene mutation is now possible with direct DNA testing in a family with an established history using amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (National Fragile X Foundation, 2010). Both affected sexes are capable of transmitting the fragile X disorder. The classic trend of physical findings in adult men with fragile X syndrome consists of a long face with a prominent jaw (prognathism); large, protruding ears; and large testes (macroorchidism). However, in prepubertal children these features may be less obvious, and behavioral manifestations may initially suggest the diagnosis (Box 37-4). In carrier females the clinical manifestations vary greatly. Fragile X syndrome has no cure. Medical treatment may include the use of serotonin agents such as carbamazepine (Tegretol) or fluoxetine (Prozac) to control violent temper outbursts and central nervous system stimulants or clonidine (Catapres) to improve attention span and decrease hyperactivity. Protein replacement and gene therapy are treatment options that are being investigated (Kuehn, 2011). Because CI is a fairly consistent finding in individuals with fragile X syndrome, the care given to these families is the same as for any child with CI. Because the disorder is hereditary, genetic counseling is necessary to inform parents and siblings of the risks of transmission. In addition, any male or female with unexplained or nonspecific mental impairment should be referred for genetic testing and, if needed, counseling. Families with a member affected by the disorder should be referred to the National Fragile X Foundation.* Hearing impairment is one of the most common disabilities in the United States. An estimated one to six per 1000 well infants have hearing loss of varying degrees (AAP Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing, 1999; Gifford, Holmes, and Bernstein, 2009). For infants admitted to neonatal intensive care units, the incidence rises sharply to approximately 2 to 4 per 100 neonates (AAP Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing, 1999). In the United States there are about 1 million children with hearing impairment ranging in age from birth to 21 years, and almost one third of these children have other disabilities such as visual or cognitive deficits. Hearing loss may be caused by a number of prenatal and postnatal conditions. These include a family history of childhood hearing impairment, anatomic malformations of the head or neck, low birth weight, severe perinatal asphyxia, perinatal infection (cytomegalovirus, rubella, herpes, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, bacterial meningitis), chronic ear infection, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, prolonged neonatal oxygen supplementation or administration of ototoxic drugs (Botelho, Bouzada, de Resende, et al., 2010; Haddad, 2007; Robertson, Howarth, Bork, et al., 2009; Weijerman and de Winter, 2010). Environmental noise is a special concern. Sounds loud enough to damage sensitive hair cells of the inner ear can produce irreversible hearing loss. Very loud, brief noise such as gunfire can cause immediate, severe, and permanent loss of hearing. Longer exposure to less intense but still hazardous sounds such as loud persistent music via headphones, sound systems, concerts, or industrial noises may also produce hearing loss (Daniel, 2007; Henderson, Testa, and Hartnick, 2011). Loud noises combined with toxic substances such as smoking or secondhand smoke produce a synergistic effect on hearing that causes hearing loss (Fabry, Davila, Arheart, et al., 2011; Mohammadi, Mazhari, Mehrparvar, et al., 2009).

Impact of Cognitive or Sensory Impairment on the Child and Family

Cognitive Impairment

General Concepts

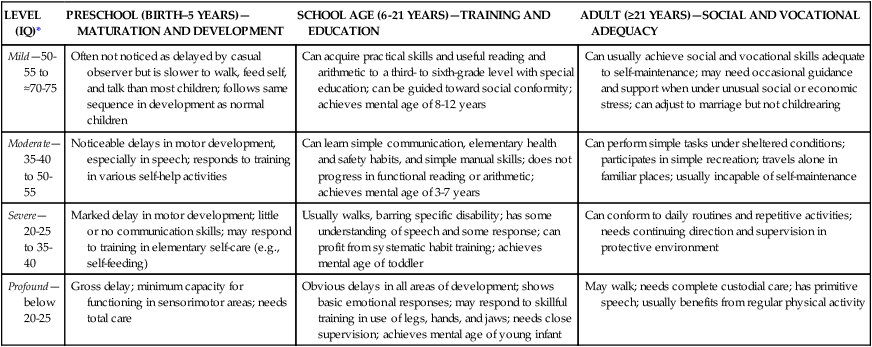

Diagnosis and Classification

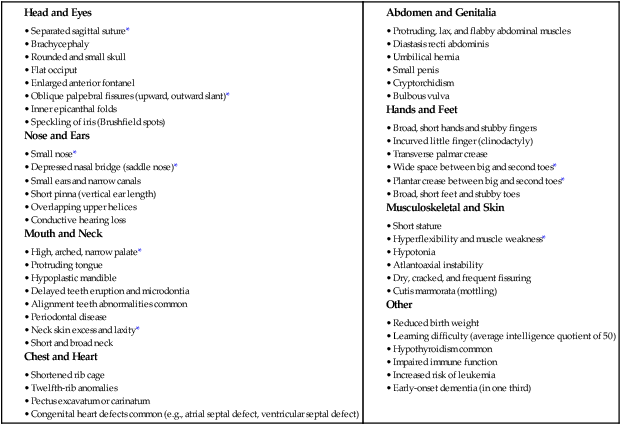

LEVEL (IQ)*

PRESCHOOL (BIRTH–5 YEARS)—MATURATION AND DEVELOPMENT

SCHOOL AGE (6-21 YEARS)—TRAINING AND EDUCATION

ADULT (≥21 YEARS)—SOCIAL AND VOCATIONAL ADEQUACY

Mild—50-55 to ≈70-75

Often not noticed as delayed by casual observer but is slower to walk, feed self, and talk than most children; follows same sequence in development as normal children

Can acquire practical skills and useful reading and arithmetic to a third- to sixth-grade level with special education; can be guided toward social conformity; achieves mental age of 8-12 years

Can usually achieve social and vocational skills adequate to self-maintenance; may need occasional guidance and support when under unusual social or economic stress; can adjust to marriage but not childrearing

Moderate—35-40 to 50-55

Noticeable delays in motor development, especially in speech; responds to training in various self-help activities

Can learn simple communication, elementary health and safety habits, and simple manual skills; does not progress in functional reading or arithmetic; achieves mental age of 3-7 years

Can perform simple tasks under sheltered conditions; participates in simple recreation; travels alone in familiar places; usually incapable of self-maintenance

Severe—20-25 to 35-40

Marked delay in motor development; little or no communication skills; may respond to training in elementary self-care (e.g., self-feeding)

Usually walks, barring specific disability; has some understanding of speech and some response; can profit from systematic habit training; achieves mental age of toddler

Can conform to daily routines and repetitive activities; needs continuing direction and supervision in protective environment

Profound—below 20-25

Gross delay; minimum capacity for functioning in sensorimotor areas; needs total care

Obvious delays in all areas of development; shows basic emotional responses; may respond to skillful training in use of legs, hands, and jaws; needs close supervision; achieves mental age of young infant

May walk; needs complete custodial care; has primitive speech; usually benefits from regular physical activity

Etiology

Nursing Care of Children with Impaired Cognitive Function

Educate Child and Family

Teach Child Self-Care Skills

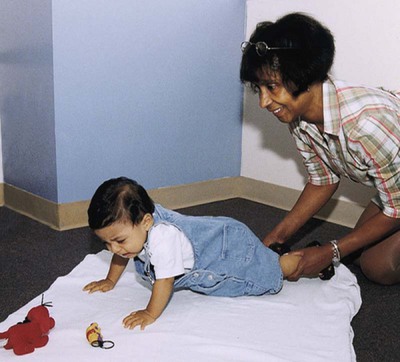

Encourage Play and Exercise

Provide Means of Communication

Encourage Socialization

Provide Information on Sexuality

Care for Child During Hospitalization

Assist in Measures to Prevent Cognitive Impairment

Down Syndrome

Etiology

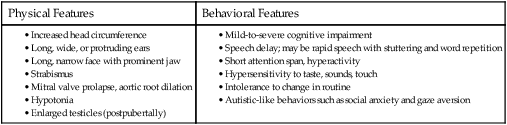

Diagnostic Evaluation

Therapeutic Management

Prognosis.

Care Management

Support Family at Time of Diagnosis.

Assist Family in Preventing Physical Problems.

Assist in Prenatal Diagnosis and Genetic Counseling.

Fragile X Syndrome

Clinical Manifestations

Therapeutic Management

Care Management

Sensory Impairment

Hearing Impairment

Etiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access