1. Describe nursing interventions for a child with Kawasaki disease 2. List nursing interventions for oral care for a child with Stevens-Johnson syndrome 3. Devise a nursing care plan for a 12-year-old with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, including teaching about home management 4. Identify characteristics for mononucleosis 5. Differentiate between insulin-dependent and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus 6. Outline the educational needs of the child with diabetes and of the parents in the following areas: nutrition and meal planning, glucose monitoring, insulin administration, and exercise Disorders of the immune system are a result of several different causes. Deficiencies of the immune cells resulting in the inability of the body to resist an infection are considered immunodeficiency. This group of disorders includes HIV/AIDS. They are discussed in Chapter 15. Other disorders are caused by an abnormal and excessive immune response to a foreign antigen. These disorders are hypersensitivity disorders such as allergies and atopic dermatitis (see Chapter 16 for further discussion on these disorders). Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute severe vasculitis of all blood vessels, especially medium-sized vessels such as the coronary artery. The cause of the illness is unknown but is thought to be infectious. It is seen in children younger than 5 years of age, in boys more often than in girls, and has a higher incidence in those of Asian background. It is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children (AAP, 2009). Coronary involvement can lead to aneurysms, ischemia, and infarcts. KD progresses through three stages: acute, subacute, and convalescent. The acute stage presents with a prolonged high fever that is unresponsive to antimicrobials or acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Additional classic symptoms are conjunctival redness without drainage, strawberry tongue with oral and pharyngeal redness, red swollen hands and feet, rash on the trunk, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, and extreme irritability. The subacute stage begins after 1 to 2 weeks when the fever and acute signs resolve. Irritability, conjunctival redness, and anorexia continue with the appearance of desquamation of hands and feet, arthritis, thrombocytosis, and coronary aneurysms (Figure 19-1). This stage can last up to 4 weeks. The last stage of convalescence begins when all signs have disappeared and ends when erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) have returned to a normal value. This stage may last from 6 to 8 weeks. Treatment involves reducing inflammation with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and high-dose aspirin. It has been shown that IVIG and aspirin given within the first 10 days of onset has reduced the incidence of coronary disease (AAP, 2009). The aspirin dose is reduced after fever has been controlled for 48 hours, which usually occurs at about 14 days. Aspirin administration will continue for 6 to 8 weeks and is discontinued if there are no coronary abnormalities. Most children recover without long-term complications. Low-dose aspirin is continued indefinitely for children with coronary abnormalities, and they are followed for several months or years depending on severity. This disorder presents with flulike symptoms of fever, malaise, fatigue, and sore throat. Mucosal lesions erupt in the eyes, mouth, and entire gastrointestinal tract (Figure 19-2). Pain can be severe. Lesions may appear in crops and may take weeks to heal. There is no definitive test for diagnosis. Laboratory testing may be done to assist with diagnosis. The most common types of JIA are listed in Table 19-1. Symptoms vary from one child to the next, and each type has a distinct method of onset: systemic (acute febrile), oligoarticular (involving five joints or fewer), and polyarticular (involving more than five joints). The course is chronic, with remissions and exacerbations. Some children who present with oligoarticular progress to polyarticular. Children rarely have permanent joint deformity, although many have some functional limitations. In systemic JIA, joint symptoms may be absent at onset but do develop in most cases. Table 19-1 Major Types of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Affected joints are swollen, warm, and stiff (Figure 19-3). Joint stiffness occurs mainly in the morning or after a period of inactivity (the “gel” phenomenon). Joint effusion and thickening synovial membrane eventually erode cartilage and can cause joint destruction. If initial treatment with NSAIDs fails after adequate trial (at least 2 to 3 months of each medication chosen), other approaches are used. Systemic corticosteroids are usually avoided unless extreme disease presents. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have demonstrated effectiveness; these include hydroxychloroquin (Plaquenil) and sulfasalazine (Azulfidine). Biologics (anti-TNF agents) can be effective and include etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), and adalimumab (Humira) (Abramson, 2008). Diabetes is not a single entity but several different disorders. These disorders differ in cause, pathophysiology, and genetic predisposition. All result in disturbed glucose metabolism. Previously, DM was classified by treatment. The old classification was insulin-dependent DM (IDDM, or type 1) and non–insulin-dependent DM (NIDDM, or type 2). The American Diabetes Association now uses a classification system that includes type 1 and type 2 (Table 19-2). Table 19-2 Classification of Types of Diabetes Mellitus

Immune Disorders

Immune System

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Kawasaki Disease

Signs and Symptoms

Treatment and Nursing Care

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Signs and Symptoms

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Signs and Symptoms

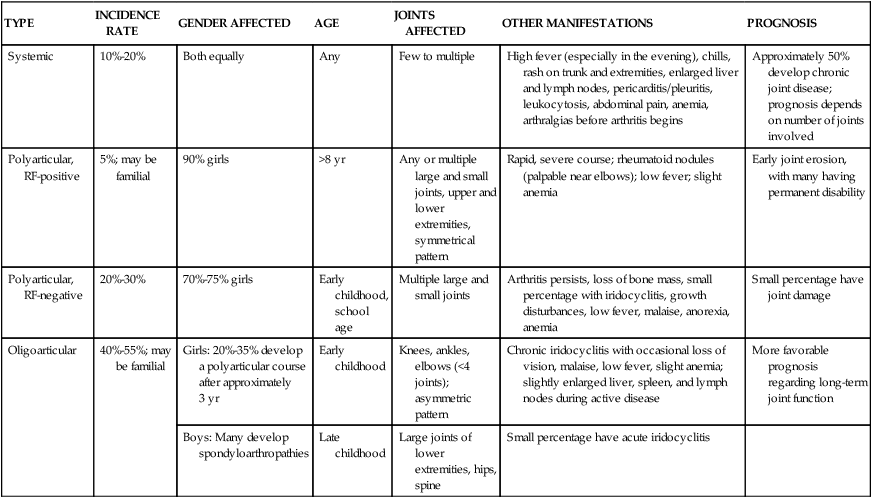

TYPE

INCIDENCE RATE

GENDER AFFECTED

AGE

JOINTS AFFECTED

OTHER MANIFESTATIONS

PROGNOSIS

Systemic

10%-20%

Both equally

Any

Few to multiple

High fever (especially in the evening), chills, rash on trunk and extremities, enlarged liver and lymph nodes, pericarditis/pleuritis, leukocytosis, abdominal pain, anemia, arthralgias before arthritis begins

Approximately 50% develop chronic joint disease; prognosis depends on number of joints involved

Polyarticular, RF-positive

5%; may be familial

90% girls

>8 yr

Any or multiple large and small joints, upper and lower extremities, symmetrical pattern

Rapid, severe course; rheumatoid nodules (palpable near elbows); low fever; slight anemia

Early joint erosion, with many having permanent disability

Polyarticular, RF-negative

20%-30%

70%-75% girls

Early childhood, school age

Multiple large and small joints

Arthritis persists, loss of bone mass, small percentage with iridocyclitis, growth disturbances, low fever, malaise, anorexia, anemia

Small percentage have joint damage

Oligoarticular

40%-55%; may be familial

Girls: 20%-35% develop a polyarticular course after approximately 3 yr

Early childhood

Knees, ankles, elbows (<4 joints); asymmetric pattern

Chronic iridocyclitis with occasional loss of vision, malaise, low fever, slight anemia; slightly enlarged liver, spleen, and lymph nodes during active disease

More favorable prognosis regarding long-term joint function

Boys: Many develop spondyloarthropathies

Late childhood

Large joints of lower extremities, hips, spine

Small percentage have acute iridocyclitis

Treatment and Nursing Care

Diabetes Mellitus

TYPE

ONSET

CLINICAL FEATURES

OTHER COMMENTS

Type 1 DM

Primarily in childhood but can occur at any age

Polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, weight loss occurring for usually less than 1 mo

Child requires insulin to maintain life

Type 1 can be diagnosed in children before symptoms appear and in family members at risk

Type 1 appears to have both genetic and environmental components

Hyperglycemia: random plasma glucose above 200 mg/dL with symptoms or fasting blood glucose above 126 mg/dL and 2-hr postprandial blood glucose above 200 mg/dL with no symptoms

Glycosuria, ketonuria

Vaginal monilial infections in adolescent girls

Elevation of antiislet or antiinsulin antibodies and presence of other indicators of immune connection

Type 2 DM

Usually after age 40 yr but can occur at any age

Hyperglycemia: fasting blood glucose above 126 mg/dL and 2-hr glucose tolerance test result above 200 mg/dL on more than one occasion without precipitating factors

Condition has some genetic basis

Some affected children need insulin on occasion (e.g., during severe stress or illness)

Child is usually obese

Serum insulin level can be normal or less than normal![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Immune Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access