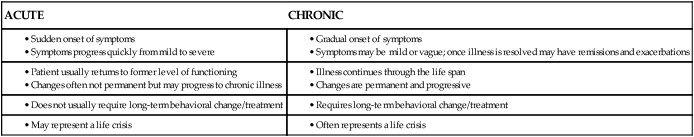

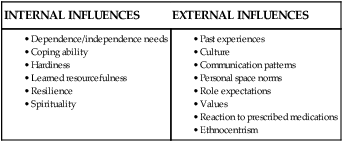

After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Differentiate between acute and chronic illness. • Describe the stages of illness. • Explain behavioral responses to illness. • Distinguish between internal and external influences on illness behaviors. • Discuss the influence of culture on illness behaviors. • Describe the characteristics of the culturally competent nurse. • Explain the concept of spiritual nursing care. • Identify spiritual nursing interventions. • Explain the physical, emotional, and cognitive effects of stress. • Describe the effect of anxiety on patient learning. • Discuss how family functioning is altered during illness. • Explain the necessity of and strategies for self-care by nurses. To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional. Joyful partners stand at the altar or before a judge on their wedding day, vowing to “have and to hold . . . in sickness and in health . . .” On a day of robust health and exuberant energy, couples rarely envision the specter of illness as they celebrate their marriage. It is a day of hope and expectation. Sickness, and all it means, has little place at the wedding. Yet as the anniversaries of this beautiful day come and go, the meaning of sickness becomes clearer. A part of life, illness affects not just the sick person, but the people providing care—the spouse, the partner, their children. Illness changes lives (Figure 10-1). In Chapter 12, you will read about systems theory in more depth, but for purposes of this chapter, it is enough to understand that a change in one part of a system results in changes in other parts. A family is system; a change in one member affects the other members. Chapter opening photo from Photos.com. Chronic illnesses have a significant social and economic impact, being one of the fastest-growing health problems in the United States. In 2005, almost one of every two adults had at least one chronic illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Factors such as sedentary lifestyles, obesity, and the aging of the population are expected to contribute to a continued increase in the number of chronically ill Americans for the foreseeable future. Chronic illnesses are pervasive and life altering. They lead to altered individual functioning and disruption of family life. Long-term medical management of chronic illness can create financial hardship as well. Patients with chronic illness need to make lifestyle changes, often many changes simultaneously. They must begin doing things they are not accustomed to doing and stop doing things they normally do. Patients with diabetes, for example, must begin monitoring their blood glucose levels and change their eating habits. Box 10-1 presents the similarities and differences between acute and chronic illnesses. The diagnosis of an acute or chronic illness can be a major life crisis. The emotional reactions of the patient and family sometimes present a greater challenge than dealing with the physical aspects of the disease. Despite the prevalence of emotional responses to illness, most medical and nursing attention is focused on physical aspects of the disease process rather than emotions. Box 10-2 describes how one patient experiences a chronic illness, systemic lupus erythematosus, and describes its effect on her feelings, family responsibilities, and relationships. As you read her thoughts and feelings, take special note of her reaction to her nurses’ focus on her physical condition at a time when her emotional responses were her greatest concern. Remember that these states are described as a means of describing how patients work through their illness. Patients do not move through these states in a linear way, nor should they be used by the student or nurse to characterize a patient’s particular response at any one time. Doing this ignores the complex changes that an illness brings to almost every element of a patient’s life. One’s response to illness is highly idiosyncratic, and it should be treated as such. Acute illness may be experienced in a very different way from chronic illness (Box 10-3). Each culture generally requires that certain criteria be met before people can qualify as “sick.” Talcott Parsons (1964), a renowned sociologist, identified five attributes and expectations of the sick role that guided the view of illness in white American society for decades. According to Parsons, the sick white American: Migration has changed the world and requires that nurses are educated to attain a level of cultural competence. Cultural competence is having “the attitudes, knowledge and skills necessary for providing quality care to diverse populations” (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2008). Culturally competent nurses are prepared to provide patient-centered care with a focus on the patient’s specific needs that are shaped by culture. Being culturally competent means that nurses are more likely to be attuned to the massive problem of health disparities. Cultural competence does not mean, however, that nurses learn every facet in detail of each culture’s practices. In fact, mastering the subtleties of every culture is impossible. Responses to illness vary widely and are, of course, idiosyncratic. Each person in whom diabetes, for example, is newly diagnosed behaves differently from other people with the same condition. Both internal and external variables affect how an individual acts when ill (Box 10-4). An individual’s personality has a great deal of influence on the response to illness. Past experiences with illness and cultural background also influence illness behaviors. People who perceive themselves as helpless may be more willing to submit to health care personnel and do what they are told. Those who are used to being in charge and see themselves as independent may resent the enforced dependency of hospitalization and illness. These two different attitudes are illustrated in Case Study 10-1. Both overly dependent and overly independent behavior can be frustrating to nurses, who sometimes become angry with patients who request help with activities they are capable of doing themselves. The patient who is too dependent requires encouragement to assume more responsibility. The patient who needs to be “in charge” may have problems turning control over to caregivers and is often too independent. This patient needs assistance in recognizing limitations and using available resources to meet his or her needs. For instance, Mr. Johnson in Case Study 10-1 risks a fall and injury by not recognizing that his recent surgery will require him to be temporarily more dependent than he is comfortable with. Sick people use coping strategies to deal with the negative consequences of the disorder, such as pain or physical limitations. Each individual has a unique coping repertoire that is formed across previous illness episodes, modeling coping by others, and by significant factors in the context of his or her life over which he or she has little or no control, such as poverty, concurrent losses, tenuous employment, and unstable relationships, among others. Higher levels of life stresses are associated with patients’ perceptions of severe consequences of illness and less control over the illness (Karademas, Karamvakalis, Zarogiannos, 2009). Resourcefulness refers to the use of cognitive skills that minimize the negative effects of thoughts and feelings on one’s daily life and the way one adjusts to adversity (Bekhet and Zauszniewski, 2008). Throughout life, individuals acquire a number of skills that enable them to cope effectively with stressful situations. Resourceful people may have an attitude of self-mastery that can be particularly helpful in reducing the feelings of despair and helplessness that can accompany the numerous stressors of chronic illness. Note that “resource” does not refer to material belongings, but involves the ability to make the most out of what one has. Scholars studying human behavior have often noted that some children did well in spite of difficult circumstances that defeated others. They attributed the differing reactions as a function of the phenomenon of resilience. Resilience is an aspect of coping that can be defined as “a pattern of successful adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances” (Humphreys, 2001). Resilient responses are thought to be a result of three factors: 1. Disposition (i.e., temperament, personality, overall health and appearance, and cognitive style) 2. Family factors such as warmth, support, and organization 3. Outside support factors, such as a supportive network and success in school or work The study of resilience has broadened to include adolescents and adults who face difficult, traumatic, or adverse circumstances. It has also been applied to adults with critical illness, battered women, survivors of sexual abuse, and others. You can expect to see much more about resilience as this phenomenon continues to be studied and better understood. A useful website (www.apa.org/helpcenter) sponsored by the American Psychological Association, includes links to a lengthy brochure “The Road to Resilience.” This document may be useful to you personally as you work to improve your own set of coping skills as you enter the profession of nursing. You may have occasion to use the content in caring for a patient who is struggling with a serious illness. The role of spiritual beliefs in health and illness has only recently been formally investigated. A growing number of scholars and health professionals think that spiritual beliefs have psychological, medical, and financial benefits that can be proved scientifically. Questions about the effects of intercessory prayer (prayer by others on behalf of a sick person) have been debated. A scientifically rigorous, privately funded study of more than 1800 patients who had heart surgery was conducted over nearly a decade. To the disappointment of many, it found that intercessory prayer had no effect on recovery (Carey, 2006). In fact, 59% of participants who knew that someone was praying for them had postoperative complications, as opposed to 51% who were uncertain about whether they were being prayed for. The debate will undoubtedly continue. One of the leading proponents of the spirituality and healing movement in American medicine is Dr. Herbert Benson. He originated the “relaxation-response” therapy to reduce stress in patients with hypertension, chronic pain, and other stress-related illnesses. Many people use prayer as part of the relaxation response (Benson and Klipper, 2000). Massachusetts General Hospital, a large medical center associated with the Harvard School of Medicine, is the home of the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine. Their website (www.massgeneral.org/bhi) describes the institute as “a world leader in the study, advancement, and clinical practice of mind/body medicine.” Mind/body medicine incorporates the relaxation response, positive coping strategies, physical activity, good nutrition, and social support (www.massgeneral.org/bhi/faq). The Joint Commission, the International Council of Nurses, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing all acknowledge that spiritual nursing care is a responsibility that goes beyond calling the chaplain. Yet many nurses are reluctant to render spiritual nursing care. This reluctance may grow from feelings of inadequacy, lack of knowledge, embarrassment, their own spiritual uncertainty, lack of preparation, lack of privacy, lack of time, or failure to see it as a nursing role (McEwen, 2005). Nurses are encouraged to view spirituality as one aspect of the whole human person and to assess patients for spiritual distress. They should recognize the individuality and value of each patient’s spiritual beliefs and encourage their use in coping with illness. Spiritual distress is a NANDA International (NANDA-I) (2009) diagnosis meaning “impaired ability to experience and integrate meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, and/or a power greater than oneself” (p. 301). Patients who question the meaning of suffering and the meaning of life, who express anger at God or an other deity, or who view illness as punishment from their deity are experiencing spiritual distress. Spiritual distress can be painful and can hinder a patient’s progress. According to Eldridge (2007), nurses can help free a patient’s energy for healing by providing spiritual care. Sometimes patients ask nurses to pray with them or for them. If you are not comfortable with this, you can simply say, “Would you like for me to sit with you while you pray?” You can simply sit in silence, and, if the patient agrees, hold his or her hand while he or she prays (Figure 10-2). If you are not someone for whom prayer is part of your spiritual practice, you can simply tell patients who asks you to pray for them that you will have good thoughts for them. If patients trust you enough to engage you in their spiritual practices, they have paid you a great compliment. In addition, it is always appropriate to ask your patients if they would like for you to call a chaplain, rabbi, priest, or other clergy for them if they have deep spiritual needs that you cannot meet. Nurses are participating in the use of spirituality in healing. St. Francis Hospital’s Congregational Nurse Program in Evanston, Illinois, for example, is reaching more than 15,000 local families in an interfaith health project. After training as congregational nurses, nurses spend approximately 20 hours weekly at churches and other places of worship providing classes, counseling, and referrals. They dovetail their efforts with the spiritual beliefs and customs of each congregation. As you learned in Chapter 1, the faith community nurse concept is being implemented in numerous communities around the United States. By respecting and treating the whole person, these practitioners are affirming that a key dimension of health and healing is the spiritual dimension. Beginning in the early 1970s, schools of nursing began including cultural concepts in their curricula. Increasing numbers of universities and colleges offered graduate programs in transcultural nursing. The Transcultural Nursing Society was incorporated in 1981, and in 1988 it began certifying nurses in transcultural nursing. Through oral and written examinations and evaluation of educational background and working experiences, a qualified nurse can become a certified transcultural nurse (CTN). More information about this interesting certification can be found at www.tcns.org/Certification.html. In the decades since transcultural nursing was first emphasized in educational programs, the cultural makeup of the U.S. population has undergone rapid change. Census demographers, who study population trends, predict that today’s ethnic and racial minorities will outnumber non-Hispanic whites by 2042. Even sooner, by 2023, they will constitute a majority of the nation’s children younger than 18 years of age (Roberts, 2008). These cultural shifts mean that changes in the nursing workforce are needed to deal more effectively with commonalities and differences in patients. Significant disparities exist between the health status of whites and nonwhites in the United States. For example, the death rate for heart disease is more than 40% higher in African Americans than in the white population. Similarly discouraging disparities exist in death rates for cancer and HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), among other diseases. Although these disparities may partly result from education, poverty, and lifestyle factors, there is a growing recognition among health professionals that racism may play a role. As a result, professional associations such as the American Nurses Association, The Joint Commission, and the federal government have all endorsed standards for culturally appropriate health care services. In 2008, The Joint Commission announced its intention to revise and develop accreditation standards for hospitals to incorporate diversity, cultural, language, and health literacy issues into patient care processes. Some states have already passed legislation requiring health care professions to include cultural competence training in their educational and continuing education programs. The profession of nursing is largely white, whereas the nation is racially more diverse than ever before, which underscores the need for culturally competent nurses. Clearly, transcultural nursing is an important field of study, practice, and research and an essential one in today’s increasingly diverse society. The Joint Commission and The California Endowment published their recommendations in a document titled One Size Does Not Fit All: Meeting the Health Care Needs of Diverse Populations (www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/HLCOneSizeFinal.pdf). The culturally competent nurse. Cultural competence, defined earlier, guides the nurse in understanding behaviors and planning appropriate approaches to patient needs. Conversely, culture will also guide the patient’s response to health care providers and their interventions. The U.S. Office of Minority Health defines culturally competent health care as “services that are respectful of and responsive to the health beliefs and practices and cultural and linguistic needs of diverse patient populations” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001, p. 131). Understanding a patient’s cultural background can facilitate communication and support establishing an effective nurse-patient relationship. Conversely, lack of understanding can create barriers that impede nursing care.

Illness, culture, and caring: Impact on patients, families, and nurses

Illness

Chronic illness

Adjustment to illness

Acceptance and participation

The sick role

Illness behaviors

Internal influences on illness behaviors

Dependence and independence.

Coping ability.

Resourcefulness.

Resilience.

Spirituality.

External influences on illness behaviors

Culture.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Illness, culture, and caring: Impact on patients, families, and nurses

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access