Chapter 2 A history of the midwifery profession in the United Kingdom

After reading this chapter, you should be able to appreciate:

The office of midwife: a female domain

What manner of women were midwives?

These midwives, however, were in a minority. Inevitably the rest attended only the poor (the majority of the population), many living in rural, perhaps isolated, places. Such women would learn their midwifery through their own and their neighbours’ birthing experiences, undertaking the work by virtue of their seniority or the large number of children they had borne (McMath 1694; Siegemundin 1690, preface). Their work might entail travelling long distances on foot to outlying habitations, for a few pence or a small payment in kind. Many such women took up the work from necessity, eking out a poor living with sick nursing and laying out the dead, as did their successors until the early 20th century.

‘In the straw’

Generally, birth took place at home, poorer women typically delivering in the communal room, before the hearth, the floor covered with straw which would later be burnt. Usually the birth chamber was darkened, windows and doors sealed, with a fire kept burning for several days. These precautions were taken lest the woman took ‘cold’ (developed the possibly lethal ‘childbed fever’), and in more superstitious households for fear that malevolent spirits might gain entrance, harming mother or infant (Gélis 1996:97, Thomas 1973:728–732). Care was taken, too, that the afterbirth and its attachments (all credited with powerful magical properties) were disposed of safely, lest they be used in spells to harm the family. These beliefs were still current in remote parts of Europe in the early 20th century.

To hasten matters on in early labour the parturient would periodically be encouraged to walk, supported by two sturdy women, her strength sustained by warm broth or spicy drinks. The midwife, sharing the universal and time-honoured belief that the child provided the motive power for its birth, would follow ancient practice in greasing and stretching the woman’s genitalia and dilating the cervix to ‘help’ the infant emerge. Hence the ‘ideal’ midwife possessed, along with appropriate qualities of character, small hands with long tapering fingers (Temkin 1956).

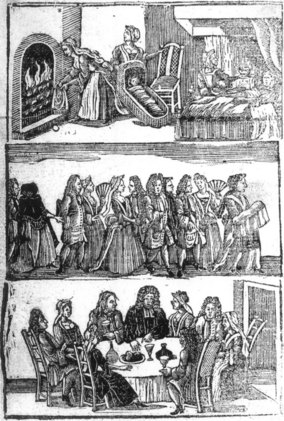

The second stage of labour usually took place, as for millennia, with the woman in an upright or semi-upright position (Kuntner 1988). In rich households a birth chair might be used, but more commonly the parturient sat on a woman’s lap. Some women knelt or stood, leaning against a support; some adopted a half-sitting, half-lying posture, with a solid object to push their feet against during contractions, while others delivered on all fours (Blenkinsop 1863:8,10,73, Gélis 1996:21–36). As labour progressed, the woman would instinctively change position, ‘as shall seeme commodious and necessarye to the partie’, as the Byrth put it, urging the midwife to comfort her with refreshments and encourage her with ‘swete wurdes’ (see Fig. 2.1). Following delivery, the mother would be put to bed to ‘lie in’ – rich women for up to a month, the poor for days at most. The infant would be washed, then swaddled to ‘straighten’ its limbs, and if circumstances permitted, an all-woman celebration of this female life event would ensue.

The midwife, the church and the law

The midwife’s duties did not end with the birth, however. In pre-Reformation times, she carried heavy responsibilities for the salvation of the infant’s soul, being required to take weakly infants directly to the priest for baptism. If death seemed imminent, she should perform the ceremony herself, taking care on pain of severe punishment to use only the Church’s prescribed words. If the woman died undelivered, she was immediately to open the body, and if the infant were alive, to baptise it. Stillborn infants, in their unhallowed state unfit for Christian burial, she was to bury in unconsecrated ground, safely and secretly, where neither man nor beast would find them. Baptism would generally take place within a week of birth, and the midwife, infant in arms, headed the procession to the church, the mother remaining in seclusion until she had been ‘churched’. The midwife enjoyed an honoured place at post-christening celebrations and in prosperous households would be liberally tipped by family and friends (see Fig. 2.2). Later, after the lying-in period, she would accompany the mother to her ‘churching’ – originally a ‘purification’ ceremony, but under Protestantism merely one of maternal thanksgiving.

The midwife also had an important role in legal matters. Where a woman condemned to death pleaded pregnancy in the hope of postponing or mitigating punishment, a panel of midwives would be summoned to examine her, though some post-execution dissections demonstrated these examinations’ unreliability (Pechey 1696:55–56). Midwife panels were also called to examine unmarried women alleging rape, women accused of aborting themselves or of concealing the birth (and possible murder) of an unwanted infant, or determine the alleged prematurity of infants born within less than 9 months of marriage. Midwives attending an unmarried woman were also expected to make her name the father, lest he escape the Church’s punishment for fornication and his responsibility to the parish for the child’s upkeep.

Governing the midwife

Probably the first system of compulsory midwife licensing in Europe was instituted in the city of Regensberg in Bavaria in 1452, a system gradually emulated in other European cities. Applicants for a licence were commonly examined by a panel of physicians, who, innocent of practical midwifery, based their examination on classical texts. Generally, midwives were required to send for a physician or surgeon in difficult cases, and in Strasbourg, midwives were prohibited from using hooks or sharp instruments on pain of corporal punishment. Many cities appointed midwives to serve the poor, supplementing their remuneration with payment in kind and providing financial aid in old age or disability (Gélis 1988:25, Wiesener 1993:78–84).

Advent of the man-midwife

Maternal mortality

Interestingly, Willughby also links such interference with the woman ‘taking cold’ (Blenkinsop 1863:6), a likely reference to ‘puerperal’ fever, not so named, but recognized under ‘fevers’ and ‘agues’ occurring after childbearing. Following ancient humoral theory, the condition was ascribed to a bodily ‘humours’ imbalance (Jonas 1540: xxxiii, Sharp 1671:243–250) and was probably then, as later, the chief single cause of maternal death. Not until the late 18th century was it publicly proposed that this deadly malady might be carried to the woman on the attendants’ clothing or unwashed hands (Gordon 1795:98–99), a view not completely accepted, even in medical circles, until the 1940s.

Midwives under threat

When urging midwives to study anatomy, Jane Sharp had recognized that women’s exclusion from the universities and ‘schools of learning’, where this was taught, disadvantaged them compared with men. Girls were barred, too, from grammar schools, which taught Latin, knowledge of which was the mark of an educated person and which was still used for many medical texts. Leading male practitioners therefore enjoyed higher social status than midwives, however successful. Although in 1762 Mrs Draper delivered the future George IV, with Dr Hunter and the surgeon Caesar Hawkins waiting elsewhere, Hunter’s diary makes their relative ranking clear (Stark 1908). Moreover, the distinction of great 18th-century practitioners like Manningham, Ould, Hunter and Smellie was to reflect credit on every man-midwife, deserved or not.

’Towards a complete new system of midwifery’

By the mid-18th century, male practitioners, disdaining the familiar ‘man-midwife’, began to adopt the French term ‘accoucheur’, as conveying greater status. Their approaches to delivery varied, however. Some still dilated the cervix and the labia vulvae, practices continuing among the more ignorant at the century’s close (Clarke 1793:21). Some extracted the placenta immediately after delivery by introducing the hand into the uterus, while others roundly condemned this (Smellie 1752–64:238–239). The general trend, however, was towards less intervention. This development stemmed from the new realization that it was not exertions by the child but uterine muscular action that provided the necessary expulsive force (ibid. 202). Significantly, Smellie (since regarded as the ‘father of British obstetrics’) concluded from his vast experience that, out of 1000 parturients, 990 would be safely delivered ‘without any other than common assistance’ (ibid. 195–196).

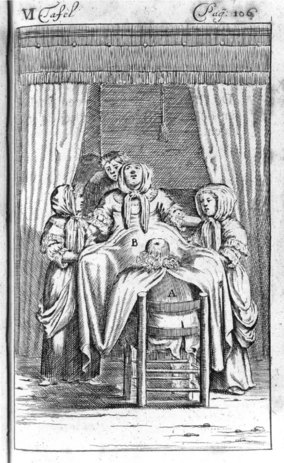

Though ambulation in the first stage was still encouraged, women’s freedom to choose their delivery position was gradually being curtailed. Earlier authorities, male and female, had encouraged women to adopt the position most comfortable to them as facilitating the best outcome for mother and infant. Smellie underlined the advantages of upright positions in furthering labour, partly through gravity, and partly through the ‘equalisation of the uterine force’, recommending them for ‘tedious labours’ (ibid. 202). Yet, along with other authorities, Smellie generally advised delivery in bed (half-sitting, half-lying) for fear that otherwise the woman might take ‘cold’, and hence develop ‘childbed fever’ (ibid. 204). Others, like Dr John Burton of York, favoured the ‘dorsal’ and ‘left lateral’ positions as ‘easiest for the Patient and most convenient for the Operator’ (Burton 1751:106–107). Indeed, sitting by the edge of the bed, his hand concealed under the sheet, was less tiring and less undignified for men hoping for recognition of their art as part of medicine proper, than was crouching at the woman’s knees on the midwife’s low stool (see Fig. 2.3).

The decline of the midwife

The end of the midwife?

The midwife’s image had not been helped by Charles Dickens’ caricature in Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) of the unsavoury ‘Mrs Gamp’, a poor widow who, like so many over the centuries, earned her living by practising midwifery, sick and ‘monthly’ nursing, and laying out the dead. A blowsy, tippling, unscrupulous character, Mrs Gamp soon became the stereotypical midwife (see Fig. 2.4). But although along with Farr some medical men advocated the replacement of such midwives by respectable, trained women, certain accoucheurs, seeking a male monopoly of midwifery (achieved in North America by the 1950s), were pressing for the midwife’s total abolition. ‘All midwives are a mistake’, Tyler Smith told his students at the Hunterian Medical School in 1847, ‘and it should be the aim of every obstetric practitioner to discourage their employment’. Furthermore, because of its origin, the word ‘midwifery’ should no longer be used to describe male attendance on childbirth, being replaced by the new construct ‘obstetrics’. Here Smith well understood that a term of Latin origin, even if derived actually from the Latin for ‘midwife’ (‘obstetrix’), had a snob value which would further elevate men above their female competitors. This substitution of ‘obstetrics’ for ‘midwifery’ in male practice was, however, not fully achieved until after World War II.

The midwives institute, midwife registration and maternal mortality

Accepting this reality, in 1880 three educated midwives, together with Louisa Hubbard, a wealthy pioneer in women’s employment, formed the Matrons Aid Society, later to become the Midwives Institute and ultimately the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) (Fig. 2.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree