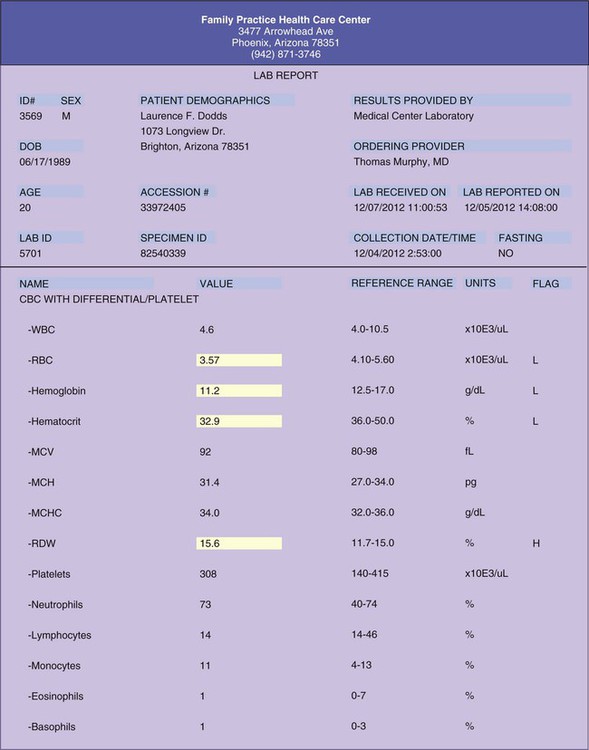

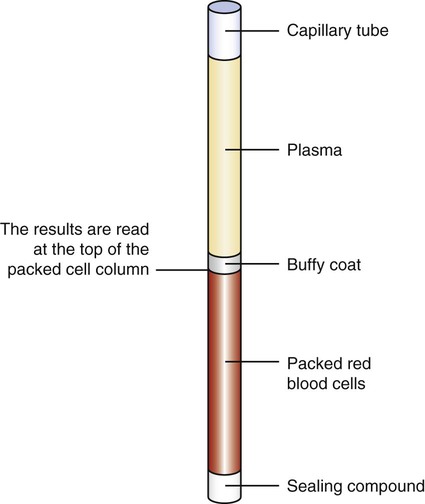

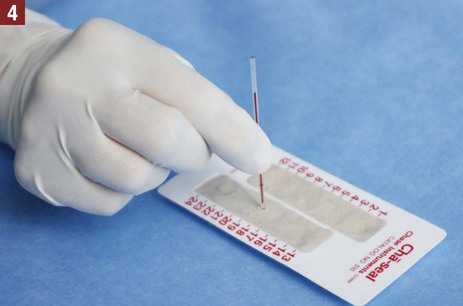

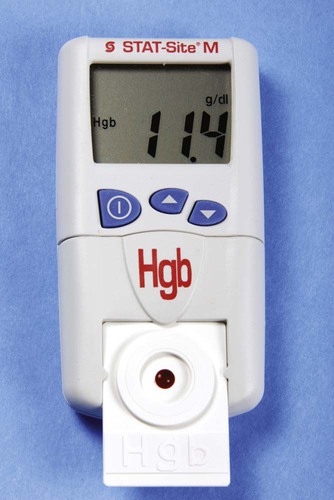

Hematology is the study of blood, including the morphologic appearance and function of blood cells and diseases of the blood and blood-forming tissues. Before beginning a study of this chapter, it is suggested that you review the components and function of blood presented in Chapter 12. An example of a laboratory report indicating the results of a CBC is presented in Figure 32-1. The hemoglobin determination can be performed on capillary or venous blood. Hemoglobin can be measured in the medical office using a hemoglobin analyzer. A hemoglobin analyzer permits processing of the specimen in a short time with accurate and reliable test results, allowing the physician to evaluate the condition while the patient is still at the medical office. Examples of CLIA-waived hemoglobin analyzers often used in the medical office include the Hemoglobin Hb 201+ Analyzer (HemoCue, Inc., Lake Forest, Calif.) and the Stat-Site Hgb Meter (Stanbio Laboratory, Boerne, Tex.) (Figure 32-2). One of the primary advantages of using a hemoglobin analyzer is that it requires only a finger puncture to perform the test rather than a venous blood specimen collected through a venipuncture. The manufacturer of each hemoglobin analyzer provides an operating manual (and sometimes an instructional video) with the instrument that includes information needed to perform quality control procedures, precautions to take when running the test, and information on storage and stability of the testing devices (e.g., testing cards or cuvettes) and control reagents, collection of the specimen, and the procedure for testing the specimen. It is important that the medical assistant become completely familiar with all aspects of the hemoglobin analyzer. Quality control procedures are of particular importance to ensure that the analyzer is functioning properly, and that test results are reliable and accurate. (Refer to Chapter 29, Quality Control, to review quality control guidelines for laboratory testing.) The hematocrit (Hct) is a simple, reliable, and informative test that is frequently performed in the medical office. The word hematocrit means “to separate blood.” The solid or cellular elements are separated from the plasma by centrifuging an anticoagulated blood specimen. The heavier red blood cells become packed and settle to the bottom of a tube. The top layer contains the clear, straw-colored plasma. Between the plasma and the packed red blood cells is a small, thin, yellowish-gray layer known as the buffy coat, which contains the platelets and white blood cells (Figure 32-3). The microhematocrit method is used most often in the medical office to perform a hematocrit determination. Through capillary action, blood is drawn directly from a free-flowing skin puncture into a disposable capillary tube lined with an anticoagulant. An anticoagulated blood specimen collected by venipuncture also can be used; through capillary action, the blood specimen is drawn into the capillary tube from the evacuated collection tube. After the specimen is collected, one end of the capillary tube is sealed with a commercially prepared sealing compound (e.g., Cha-Seal [Chase Scientific, Langley, Wash.], Seal-Ease [Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ]). The capillary tube is then placed in a microhematocrit centrifuge. The centrifuge spins the blood at an extremely high speed; only 3 to 5 minutes are required to pack the red blood cells. The results are read at the top of the packed cell column. Procedure 32-1 describes how to perform a hematocrit determination.

Hematology

Introduction to Hematology

Hemoglobin Determination

Hematocrit

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Hematology

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access