Health Promotion for the School-Age Child

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Discuss the effect school has on the child’s development and implications for teachers and parents.

• Describe anticipatory guidance that the nurse can offer to decrease children’s stress.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Middle childhood, ages 6 to 11 or 12 years, is probably one of the healthiest periods of life. Slow, steady physical growth and rapid cognitive and social development characterize this time. During these years, the child’s world expands from the tight circle of the family to include children and adults at school, at a worship community, and in the community at large. The child becomes increasingly independent. Peers become important as the child starts school and gradually moves away from the security of home. This period is a time for best friends, sharing, and exploring.

The school years also are a time that can be stressful for a child, and this stress can impede the child’s successful achievement of developmental tasks. The Healthy People 2020 objectives that relate to school-age children include such goals as reducing obesity, improving nutrition, facilitating access to dental and mental health care, increasing physical activity, and preventing high-risk behaviors.

Growth and Development of the School-Age Child

The school-age child develops a sense of industry (Erikson, 1963) and learns the basic skills needed to function in society. The child develops an appreciation of rules and a conscience. Cognitively, the child grows from the egocentrism of early childhood to more mature thinking. The ability to solve problems and make independent judgments that are based on reason characterizes this new maturity. The child is invested in the task of middle childhood: learning to do things and do them well. Competence and self-esteem increase with each academic, social, and athletic achievement. The relative stability and security of the school-age period prepare the child to enter the emotional and physical changes of adolescence.

Physical Growth and Development

The school-age years are characterized by slow and steady growth. The physical changes that occur during this period are gradual and subtle. Although growth rates vary among children (Figure 8-1), the average weight gain is 2.5 kg (5½ lb) per year, and the average increase in height is approximately 5.5 cm (2 inches) per year. During the early school-age period, boys are approximately 1 inch taller and 2 lb heavier than girls. At around age 10 or 11 years, girls begin to catch up in size as they undergo the preadolescent growth spurt. By age 12 years, girls are 1 inch taller than boys and 2 lb heavier. This growth spurt, which signals the onset of puberty, occurs

usually between ages 12 and 14 years and occurs 2 years later in boys than in girls.

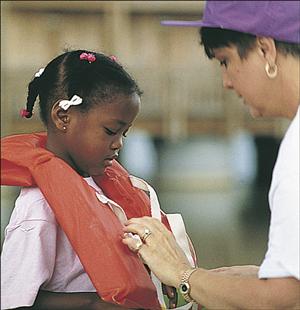

Children of the same age can vary significantly in height and physical development. School-age children often have a snaggle-tooth appearance while they are losing their primary teeth. Organizations such as Girl Scouts help foster self-esteem and competence.

Body Systems

School-age children appear thinner and more graceful than preschoolers do. Musculoskeletal growth leads to greater coordination and strength. The muscles are still immature, however, and can be injured from overuse. Growth of the facial bones changes facial proportions. As the facial bones grow, the eustachian tube assumes a more downward and inward position, resulting in fewer ear infections than in the preschool years. Lymphatic tissues continue to grow until about age 9 years; immunoglobulin A and G (IgA, IgG) levels reach adult values at approximately 10 years. Enlarged tonsils and adenoids are common during these years and are not always an indication of illness. Frontal sinuses develop at age 7 years. Growth in brain size is complete by 10 years. The respiratory system also continues to mature. During the school-age years, the lungs and alveoli develop fully and fewer respiratory infections occur.

Dentition

During the school-age years, all 20 primary (deciduous) teeth are lost and are replaced by 28 of the 32 permanent teeth. All permanent teeth, except the third molars, erupt during the school-age period. The order of eruption of permanent teeth and loss of primary teeth is shown in Figure 33-7. The first teeth to be lost are usually the lower central incisors, at around age 6 years. Most first-graders are characterized by a snaggle-tooth appearance (see Figure 8-1), and visits from the “tooth fairy” are important signs of growing up.

Sexual Development

Puberty is a time of dramatic physical change. It includes the growth spurt, development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics, and maturation of the sexual organs. The age at onset of puberty varies widely, and puberty is occurring at an earlier age than previously thought (Biro, Galvez, Greenspan, et al., 2010). Onset of puberty is no longer unusual in girls who are 8 or 9 years old. On the average, African-American girls begin puberty 1 year earlier than white girls and by age 8 years, 42.9% of African-American girls, as compared to 18.3% of white girls, demonstrate initial signs of pubertal development (e.g., breast budding; Biro et al., 2010). The reason for the earlier development among African-American girls is not known; however, recent research suggests that it may be related to food intake patterns. Puberty begins about 1½ to 2 years later in boys.

Menarche, the onset of menstruation, occurs, on average, during the 12th year, however, with the decrease in the age of puberty onset, the age at menarche is also likely to decrease.

Females who are significantly overweight tend to have earlier onset of puberty and menarche. Because puberty is occurring increasingly earlier, many 10- and 11-year-old girls have already had menarche. Wide variations in maturity at this age are a common cause of embarrassment because the school-age child does not want to appear different from peers. Children who mature either early or late may struggle with feelings of self-consciousness and inferiority. Table 9-1 describes the usual sequence of appearance of secondary sex characteristics during the school-age and adolescent periods.

Because of the earlier onset of puberty, sex education programs should be introduced in elementary school. Nurses are in an excellent position to serve as resource persons for parents and teachers who are responsible for sex education. Children’s questions about sexuality and related issues should be answered honestly and in a matter-of-fact way. If sex education is presented within the context of learning about the human body, with its wonders and mysteries, children are less likely to feel embarrassed and anxious. Regardless of whether sex education is a part of a formal school curriculum, children need accurate information. Basic anatomy and physiology, information about body functions, and the expected changes of puberty should be introduced to children before the onset of puberty. Older school-age children need information about menstruation, nocturnal emissions, and reproduction. Sex education programs must also include information about responsible sexuality and related issues, such as teenage pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

Motor Development

Development of Gross Motor Skills

During the school years, coordination improves. A developed sense of balance and rhythm allows children to ride a two-wheeled bicycle, dance, skip, jump rope, and participate in a variety of sports. As puberty approaches in the late school-age period, children may become more awkward as their bodies grow faster than their ability to compensate.

Importance of Active Play

School-age children spend much of their time in active play, practicing and refining motor skills. They seem to be constantly in motion. Children of this age enjoy active sports and games, as well as crafts and fine motor activities (Box 8-1). Activities requiring balance and strength, such as bicycle riding, tree climbing, and skating, are exciting and fun for the school-age child. Coordination and motor skills improve as the child is given an opportunity to practice.

Children should be encouraged to engage in physical activities. During the school-age years, children learn physical fitness skills that contribute to their health for the rest of their lives. Cardiovascular fitness, strength, and flexibility are improved by physical activity. Popular games such as tag, jump rope, and hide-and-seek provide a release of emotional tension and enhance the development of leader and follower skills.

Team sports, such as soccer and baseball, provide opportunities not only for exercise and refinement of motor skills but also for the development of sportsmanship and teamwork. Nurses should advise parents on ways to prevent sports injuries and

how to assess a recreational sports program (see the Patient-Centered Teaching box: Assessing an Organized Recreational Sports Program). Sports activities should be well supervised, and protective gear (e.g., helmets for T-ball, shin guards for soccer) should be mandatory.

Obesity has become a major problem in children in the United States, with 20% of children ages 6 to 11 years being overweight (National Center for Health Statistics, 2011). Time spent watching television, watching movies or playing computer games often diminishes a child’s interest in active play outside. Nurses can help reverse this trend by advising parents to limit their children’s television watching time to 2 hours or less per day and to encourage them to engage in more active play. Parents need to provide adequate space for children to run, jump, and scuffle. Children should have enough free time to exercise and play. Parents need to act as role models for both good nutrition and exercise.

Preventing Fatigue and Dehydration

Because children enjoy active play and are so full of energy, they often do not recognize fatigue. Six-year-olds in particular will not stop an activity to rest. Parents must learn to recognize signs of fatigue or irritability and enforce rest periods before the child becomes exhausted. Because the child’s metabolic rate is higher than an adult’s and sweating ability is limited, extremes in temperature while exercising can be dangerous. Dehydration and overheating can pose threats to the child’s health. Frequent rest periods and adequate hydration are essential for the child during physical exercise.

Development of Fine Motor Skills

Increased myelinization of the central nervous system is shown by refinement of fine motor skills. Balance and hand-eye coordination improve with maturity and practice. School-age children take pride in activities that require dexterity and fine motor skill, such as model building, playing a musical instrument, and drawing.

Cognitive Development

Thought processes undergo dramatic changes as the child moves from the intuitive thinking of the preschool years to the logical thinking processes of the school-age years. The school-age child gains new knowledge and develops more efficient problem-solving ability and greater flexibility of thinking. The 6-year-old and the 7-year-old remain in the intuitive thought stage (Piaget, 1962) characteristic of the older preschool child. By age 8 years, the child moves into the stage of concrete operations, followed by the stage of formal operations at around 12 years (Piaget, 1962). See Chapter 5 for a discussion of formal operations and Chapter 54 for a discussion of the child with cognitive deficits, including intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Intuitive Thought Stage

In the intuitive thought stage (6 to 7 years), thinking is based on immediate perceptions of the environment and the child’s own viewpoint (Piaget, 1962). Thinking is still characterized by egocentrism, animism, and centration (see Chapter 7). At 6 and 7 years old, children cannot understand another’s viewpoint, form hypotheses, or deal with abstract concepts. The child in the intuitive thought stage has difficulty forming categories and often solves problems by random guessing.

Concrete Operations Stage

By age 7 or 8 years, the child enters the stage of concrete operations. Children learn that their point of view is not the only one as they encounter different interpretations of reality and begin to differentiate their own viewpoints from those of peers and adults (Piaget, 1962). This newly developed freedom from egocentrism enables children to think more flexibly and to learn about the environment more accurately. Problem solving becomes more efficient and reliable as the child learns how to form hypotheses. The use of symbolism becomes more sophisticated, and children now can manipulate symbols for things in the way that they once manipulated the things themselves. The child learns the alphabet and how to read. Attention span increases as the child grows older, facilitating classroom learning.

Reversibility

Children in the concrete operations stage grasp the concept of reversibility. They can mentally retrace a process, a skill necessary for understanding mathematic problems (5 + 3 = 8 and 8 − 3 = 5). The child can take a toy apart and put it back together or walk to school and find the way back home without getting lost. Reversibility also enables a child to anticipate the results of actions—a valuable tool for problem solving.

The understanding of time gradually develops during the early school-age years. Children can understand and use clock time at around age 8 years. Although 8- or 9-year-old children understand calendar time and memorize dates, they do not master historic time until later.

Conservation

Gradually, the school-age child masters the concept of conservation. The child learns that certain properties of objects do not change simply because their order, form, or appearance has changed. For example, the child who has mastered conservation of mass recognizes that a lump of clay that has been pounded flat is still the same amount of clay as when it was rolled into a ball. The child understands conservation of weight when able to correctly answer the classic nonsense question, “Which weighs more, a pound of feathers or a pound of rocks?” The concept of conservation does not develop all at once. The simpler conservations, such as number and mass, are understood first, and more complex conservations are mastered later. An understanding of conservation of weight develops at 9 or 10 years old, and an understanding of volume is present at 11 or 12 years.

Classification and Logic

Older school-age children are able to classify objects according to characteristics they share, to place things in a logical order, and to recall similarities and differences. This ability is reflected in the school-age child’s interest in collections. Children love to collect and classify stamps, stickers, sports cards, shells, dolls, rocks, or anything imaginable. School-age children understand relationships such as larger and smaller, lighter and darker. They can comprehend class inclusion—the concept that objects can belong to more than one classification. For example, a man can be a brother, a father, and a son at the same time.

School-age children move away from magical thinking as they discover that there are logical, physical explanations for most phenomena. The older school-age child is a skeptic, no longer believing in Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny.

Humor

Children in the concrete operations stage have a delightful sense of humor. Around age 8 years, increased mastery of language and the beginning of logic enable children to appreciate a play on words. They laugh at incongruities and love silly jokes, riddles, and puns (“How do you keep a mad elephant from charging? You take away its credit cards!”). Riddle and joke books make ideal gifts for young school-age children. Evidence from multiple disciplines that address the needs of children suggests that children who have a good sense of humor may use it as a positive coping mechanism for stress associated with painful procedures and other situational life events.

Sensory Development

Vision

The eyes are fully developed by age 6 years. Visual acuity, ocular muscle control, peripheral vision, and color discrimination are fully developed by age 7 years. Just before puberty, some children’s eyes undergo a growth spurt, resulting in myopia. Children with poor visual acuity usually do not complain of vision problems because the changes occur so gradually that they are difficult to notice. Usual behaviors that parents notice include squinting, moving closer to the television, or complaints of frequent headaches. The young child may never have had 20/20 vision and has nothing with which to compare the imperfect vision. For these reasons, yearly vision screening is important for school-age children.

Hearing

With maturation and growth of the eustachian tube, middle ear infections occur less frequently than in younger children. However, chronic middle ear infections are a problem for a few children, when they result in hearing loss. Annual audiometric screening tests are important to detect hearing loss before unrecognized deficits lead to learning problems (see Chapter 55).

Language Development

Language development continues at a rapid pace during the school-age years. Vocabulary expands, and sentence structure becomes more complex. By age 6 years, the child’s vocabulary is approximately 8000 to 14,000 words. There is an increase in the use of culturally specific words at this age. Bilingual children may speak English at school and a different language at home.

Reading effectively improves language skills. Regular trips to the library, where the child can borrow books of special interest, can promote a love of reading and enhance school performance. School-age children enjoy being read to as well as reading on their own. Older children enjoy horror stories, mysteries, romances, and adventure stories.

School-age children often go through a period in which they experiment with profanity and “dirty” jokes. Children may imitate parents who use such words as part of their vocabulary.

Psychosocial Development

Development of a Sense of Industry

According to Erikson (1963), the central task of the school-age years is the development of a sense of industry. Ideally, the child is prepared for this task with a secure sense of self as separate from loved ones in the family. The child should have learned to trust others and should have developed a sense of autonomy and initiative during the preceding years. The school-age child replaces fantasy play with “work” at school, crafts, chores, hobbies, and athletics. The child is rewarded with a sense of satisfaction from achieving a skill, as well as with external rewards, such as good grades, trophies, or an allowance. School-age children enjoy undertaking new tasks and carrying them through to completion. Whether it is baking a cake, hitting a home run, or scoring 100 on a math test, purposeful activity leads to a sense of worth and competence. Successful resolution of the task of industry depends on learning to do things and do them well. School-age children learn skills that they will need later to compete in the adult world. A person’s fundamental attitude toward work is established during the school-age years.

Fostering Self-Esteem

The negative component of this developmental stage is a sense of inferiority (Erikson, 1963). If a child cannot separate psychologically from the parent or if expectations are set too high for the child to achieve, feelings of inferiority develop. If a child believes that success is unattainable, confidence is lost, and the child will not take pleasure in attempting new experiences. Children who have this experience will then have a pervasive feeling of inferiority and incompetence that will affect all aspects of their lives. The child who lacks a sense of industry has a poor foundation for mastering the tasks of adolescence. The reality is that no one can master everything. Every child will feel deficient or inferior at something. The task of the caring parent or teacher is to identify areas in which a child is competent and to build on successful experiences to foster feelings of mastery and success. Nurses can suggest ways in which parents and teachers can promote a sense of self-esteem and competence in school-age children (see the Patient-Centered Teaching box: How to Promote Self-Esteem in School-Age Children).

At this age, the approval and esteem of those outside the family, especially peers, become important. Children learn that their parents are not infallible. As they begin to test parents’ authority and knowledge, the influence of teachers and other adults is felt more and more. The peer group becomes the school-age child’s major socializing influence. Although parents’ love, praise, and support are needed, even craved during stressful times, the child begins to prefer activities with friends to activities with the family. As the child becomes more independent, increasing time is spent with friends and away from the family.

The concept of friendship changes as the child matures. At 6 and 7 years old, children form friendships merely on the basis of who lives nearby or who has toys that they enjoy. By the time children are 9 or 10 years old, friendships are based more on emotional bonds, warm feelings, and trust-building experiences. Children learn that friendship is more than just being together. Children at 11 and 12 years are loyal to their friends, often sharing problems and giving emotional support. School-age children tend to form friendships with peers of the same sex. Developing friendships and succeeding in social interactions lead to a sense of industry. Friendships are important for the emotional well-being of school-age children. Friends teach children skills they will use in future relationships.

Children learn a body of rules, sayings, and superstitions as they enter the culture of childhood. Rules are important to children because they provide predictability and offer security. Learning the sayings, jokes, and riddles is an important part of social interaction among peers. Sayings such as “Step on a crack and you’ll break your mother’s back” or “Finders, keepers; losers, weepers” have been part of childhood lore for generations.

Children become sensitive to the norms and values of the peer group because pressure to conform is great. Children often find that it is painful to be different. Peer approval is a strong motivating force and allows the child to risk disapproval from parents.

The school-age years are a time of formal and informal clubs. Informal clubs among 6-, 7-, and 8-year-olds are loosely organized, with fluid membership. Membership changes frequently, and it is based on mutual interests, such as playing ball, riding bicycles, or playing with dolls. Children learn interpersonal skills, such as sharing, cooperation, and tolerance, in these groups.

Clubs among older school-age children tend to be more structured, often characterized by secret codes, rituals, and rigid rules. A club may be formed for the purpose of exclusion, in which children snub another child for some reason.

Formal organizations, such as Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, Camp Fire USA, and 4-H, organized by adults, also foster self-esteem and competence as children earn ranks and merit badges. Transmission of societal values, such as service to others, duty to God, and good citizenship, is an important goal of these organizations.

Spiritual and Moral Development

Middle childhood years are pivotal in the development of a conscience and the internalization of values. Tremendous strides are made in moral development during these 6 years. Several theorists have described the dramatic growth that occurs during this stage.

Piaget

Piaget (1962) asserted that young school-age children obey rules because powerful, all-knowing adults hand them down. During this stage, children know the rules but not the reasons behind them. Rules are interpreted in a literal way, and the child is unable to adjust rules to fit differing circumstances. The perception of guilt changes as the child matures. Piaget stated that up to approximately age 8 years, children judge degrees of guilt by the amount of damage done. No distinction is made between accidental and intentional wrongdoing. For example, the child believes that a child who broke five china cups by accident is guiltier than a child who broke one cup on purpose. By age 10 years, children are able to consider the intent of the action. Older school-age children are more flexible in their decisions and can take into account extenuating circumstances.

Kohlberg

Kohlberg (1964) described moral development in terms of three levels containing six stages (see Chapter 5). According to Kohlberg’s theory, children 4 to 7 years old are in stage 2 of the preconventional level, in which right and wrong are determined by physical consequences. The child obeys because of fear of punishment. If the child is not caught or punished for an act, the child does not consider the act wrong. At this stage, children conform to rules out of self-interest or in terms of what others can do in return (“I’ll do this for you if you’ll do that for me.”). Behavior is guided by an eye-for-an-eye philosophy.

Kohlberg describes children between ages 7 and 12 years as being in stage 3 of the conventional level. A “good-boy” or “good-girl” orientation characterizes this stage, in which the child conforms to rules to please others and avoid disapproval. This stage parallels the concrete operations stage of cognitive development. Around age 12 years, children enter stage 4 of the conventional level. There is an orientation toward respecting authority, obeying rules, and maintaining social order. Most religions place the age of accountability at approximately 12 years.

Family Influence

Children manifest antisocial behaviors during middle childhood. Behaviors such as cheating, lying, and stealing are not uncommon. Often, children lie or cheat to get out of an embarrassing situation or to make themselves look more important to their peers. In most cases, these behaviors are minor; however, if they are severe or persistent, the child may need referral for counseling.

Parents and teachers profoundly influence moral development. Parents can teach children the difference between right and wrong most effectively by living according to their values. A father who lectures his child about the importance of honesty gives a mixed message when he brags about fooling his boss or cheating on his income tax return. The moral atmosphere in the home is a critical factor in the child’s personality development.

Children learn self-discipline and internalization of values through obedience to external rules. School-age children are legalistic, and they feel loved and secure when they know that firm limits are set on their behavior. They want and expect discipline for wrongdoings. For moral teaching to be effective, parents must be consistent in their expectations of their children and in administering rewards and punishment.

Spirituality and Religion

Spiritually, school-age children become acquainted with the basic content of their faith. Children reared within a religious tradition feel a part of their religion. Although their thinking is still concrete, children begin to use abstract concepts to describe God and are able to comprehend God as a power greater than themselves or their parents. Because school-age children think literally, spiritual concepts take on materialistic and physical expression. Heaven and hell fascinate them. Concern for rules and a maturing conscience may cause a nagging sense of guilt and fear of going to hell. Younger school-age children still tend to associate accidents and illness with punishment for real or imagined wrong-doing. One 6-year-old child hospitalized for an appendectomy said, “God saw all the bad things I did, and He punished me.” Reassurance that God does not punish children by making them sick reduces anxiety.

Health Promotion for the School-Age Child and Family

It is recommended that during middle childhood, children should visit the health care provider at least every 2 years. Many school districts require documentation of a routine physical examination at least once during the elementary school years after the kindergarten visit. If children are participating in organized sports or attending camp, an annual physical examination might be required.

Nutrition During Middle Childhood

Nutritional Requirements

Growth continues at a slow, regular pace, but the school-age child begins to have an increased appetite. Energy needs increase during the later school-age years. Children in this age-group tend to have few eating idiosyncrasies and generally enjoy eating to satisfy appetite and as a social function. Children who developed dislikes for certain foods during earlier periods may continue to refuse those foods. School-age children are influenced by family patterns and the limitations their activities put on them. They may rush through a meal to go out to play or watch a favorite program on television.

Children need to choose a variety of culturally appropriate foods and snacks daily. Dietary recommendations for school-age children include 2½ cups of a variety of vegetables; 1½ cups of a variety of fruits; 5 ounces grains (half of which should be whole grain); 5 ounces protein (lean meat, poultry, fish, beans); and 3 cups of fortified nonfat milk or dairy products (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2011). They need to limit saturated fat intake and processed sugars. Caloric and protein requirements begin to increase at about age 11 years because of the preadolescent growth spurt. The requirements for boys and girls also begin to vary at this age. A gradual increase in food intake will also take place. The nurse should ask children to describe specifically what they eat at meals and for snacks to develop a more comprehensive picture of their eating habits.

When children’s nutritional status is assessed, it is important to also assess any body image concerns; be sure to ask children how they feel about the way they look. Eating disorders, although thought to be a problem of adolescence, can begin in the late elementary school years.

Age-Related Nutritional Challenges

During the school years, the child’s schedule changes and more time is spent away from home. Most children eat lunch at school, and they usually have a choice of foods. Even if the parent packs a lunch for the child to take to school, there are no guarantees that the child will eat the lunch. Unless specifically prohibited by the school, children sometimes trade foods with other children or they may not eat a particular item. It is also during this period that the child becomes more active in clubs, sports, and other activities that interrupt the normal meal schedule.

The federal government funds the National School Lunch Program, which provides lunches free or at a reduced cost for low-income children. The school lunch program includes approximately one third of the recommended daily dietary allowances for a child. School lunch programs usually follow the dietary guidelines to meet recommended nutritional requirements; however, many school lunches are somewhat high in fat. Some schools also offer breakfast and milk programs. Many schools offer low-nutrient, high-calorie snacks as an add-on to the school lunch or in snack machines available in various locations throughout the school. In some cases, children use their lunch money to buy snacks. Advise parents to communicate with their children about appropriate lunch and snacks in school and to know what is being offered in the school cafeteria.

School-age children usually request a snack after school and in the evening. Encourage parents to provide their children with healthy choices for snacks. By not buying foods high in calories and low in nutrients, the parent can remove the temptation for the child to choose the less healthy foods.

Unpredictable schedules, advertising, easy access to fast food, and peer pressure all have an effect on the foods a child chooses. The child may begin to prefer “junk foods,” which do not have much nutritional value. Most of these foods are high in fat and sugar. In addition, school-age children often skip breakfast. The family plays an important role in modeling good eating habits for the child. Schools also have a responsibility to provide nutritious meals for children.

Dental Care

Although the incidence of dental caries (tooth decay) has declined in recent years, tooth decay remains a significant health problem among school-age children (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2008). Unfortunately, many parents and school-age children consider dental hygiene to be of minor importance. Many parents erroneously believe that dental care, even brushing, is not important for primary teeth because they will all fall out anyway. However, premature loss of these deciduous teeth can complicate eruption of permanent teeth and lead to malocclusion.

School-age children are able to assume responsibility for their own dental hygiene. Good oral health habits tend to be carried into the adult years, reducing cavity formation for a lifetime. Thorough brushing with fluoride toothpaste followed by flossing between the teeth should be done after meals and especially before bedtime. Proper brushing and flossing and a well-balanced diet promote healthy gums and prevent cavities. Sugary or sticky between-meal snacks should be limited. Candy that dissolves quickly, such as chocolate, is less cariogenic than sticky candy, which stays in contact with teeth longer. The American Dental Association (ADA) no longer recommends routine fluoride supplementation for children who are not at risk for tooth decay (Rozier, Adair, Graham, et al., 2010).

Malocclusion

Good occlusion, or alignment, of the teeth is important for tooth formation, speech development, and physical appearance. Many school-age children need orthodontic braces to correct malocclusion, a condition in which the teeth are crowded, crooked, or out of alignment. Factors such as heredity, cleft palate, premature loss of primary teeth, and mouth breathing lead to malocclusion. Thumb sucking is not believed to cause malocclusion unless it persists past age 5 or 6 years. However, because of concern about the risk for future malocclusion, the AAP (2008) recommends that children older than 3 years not continue to use a pacifier. Malocclusion becomes particularly noticeable between ages 6 and 12 years, when the permanent teeth are erupting.

Children with braces are at increased risk for dental caries and must be scrupulous about their dental hygiene. School nurses can encourage children who wear braces to brush after every meal and snack, eat a nutritious diet, and visit the dentist at least once every 6 months. Use of a water pick keeps gums healthy and helps remove food particles from around wires and bands.

Braces cause many children to feel self-conscious and may be difficult for a school-age child to accept. However, for some children, orthodontic appliances may be a status symbol. Parental support and encouragement are important to help the child adjust to orthodontic treatment.

Preventing Dental Injuries

During the school-age years, injuries to the teeth can occur easily. Many injuries can be avoided by use of mouth protectors. These resilient shields protect against injuries by cushioning blows that might otherwise damage teeth or lead to jaw fractures (ADA, 2011). Children should wear a mouth protector when participating in contact sports, bicycle riding, or in-line skating. Custom-made mouth protectors constructed by the dentist are more expensive than stock mouth protectors purchased in stores, but their better fit makes them more comfortable and less likely to interfere with speech and breathing. Wearing a mouth protector is especially important for children with orthodontic braces; they protect against accidental disruption of the appliance as well as soft tissue injury that would occur from the contact between the orthodontic appliance and the interior of the lips and gums (ADA, 2011).

Dental Health Education

Health education curricula need to be designed to foster attitudes and behaviors among children that promote good personal oral hygiene practices and awareness of the risks of dental disease. The school nurse is in an excellent position to educate children about dental health and to detect problems such as untreated caries, inflamed gums, or malocclusion. The nurse should look for signs of smokeless tobacco use (irritation of the gums at the tobacco placement site, gum recession, stained teeth) and should take this opportunity to explain to the child the risks of using tobacco. The use of snuff and chewing tobacco carries multiple dangers, including a greatly increased risk of oral cancer and heart disease.

Sleep and Rest

The number of hours spent sleeping decreases as the child grows older. Children ages 6 and 7 years need about 12 hours of sleep per night. Some children also continue to need an afternoon quiet time or nap to restore energy levels. The 12-year-old needs about 9 to 10 hours of sleep at night. More sleep is needed when the child enters the preadolescent growth spurt. Adequate sleep is important for school performance and physical growth. Inadequate sleep can cause irritability, inability to concentrate, and poor school performance.

To promote rest and sleep, a period of quiet activity just before bedtime is helpful. A leisurely bedtime routine, with adequate time for the child to read, listen to the radio or MP3 player or just daydream, promotes relaxation. Children who do not obtain adequate rest often have difficulty getting up in the morning, creating a family disturbance as they rush to get ready for school, perhaps skipping breakfast or leaving the house in the heat of frustration. A set bedtime and waking time, consistently enforced, promote security and healthful sleep habits. Bedtime offers an ideal opportunity for parent and child to share important events of the day or give a kiss and a hug, unthinkable in front of peers earlier in the day.