Health Promotion for the Infant

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe the physiologic changes that occur during infancy.

• Describe the infant’s motor, psychosocial, language, and cognitive development.

• Discuss the importance of immunizations and recommended immunization schedules for infants.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

During no time after birth does a human being grow and change as dramatically as during infancy. Beginning with the newborn period and ending at 1 year, the infancy period, a child grows and develops from a tiny bundle of physiologic needs to a dynamo, capable of locomotion and language and ready to embark on the adventures of the toddler years.

Growth and Development of the Infant

Although historically adults have considered infants unable to do much more than eat and sleep, it is now well documented that even young infants can organize their experiences in meaningful ways and adapt to changes in the environment. Evidence shows that infants form strong bonds with their caregivers, communicate their needs and wants, and interact socially. By the end of the first year of life, infants can move about independently, elicit responses from adults, communicate through the use of rudimentary language, and solve simple problems.

Infancy is characterized by the need to establish harmony between the self and the world. To achieve this harmony, the infant needs food, warmth, comfort, oral satisfaction, environmental stimulation, and opportunities for self-exploration and self-expression. Competent caregivers satisfy the needs of helpless infants, providing a warm, nurturing relationship so that the children have a sense of trust in the world and in themselves. These challenges make infancy an exciting yet demanding period for both child and parents.

Nurses play an important role in promoting and maintaining health in infants. Although the infant mortality rate in the United States has declined markedly over the past 30 years (see Chapter 1), many infants still die before the first birthday (6.8 per 1000 live births). The leading cause of death in infants younger than 1 year of age is congenital anomalies, followed by conditions related to prematurity or low birth weight (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2011). Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), which for a long time was the second leading cause of infant deaths, is now the third leading cause of death (NCHS, 2011), primarily because of international efforts, such as the Back to Sleep campaign. Unintentional injuries rank seventh in this age-group and contribute to mortality and morbidity rates in the infant population (NCHS, 2011). Nurses provide anticipatory guidance for families with infants to reduce morbidity and mortality rates.

During the first year after birth, the infant’s development is dramatic as the child grows toward independence. Knowledge of developmental milestones helps caregivers determine whether the baby is growing and maturing as expected. The nurse needs to remember that these markers are averages and that healthy infants often vary. Some infants reach each milestone later than most. Knowledge of normal growth and development helps the nurse promote children’s safety. Nurses teach parents to prepare for the child’s safety before the child reaches each milestone.

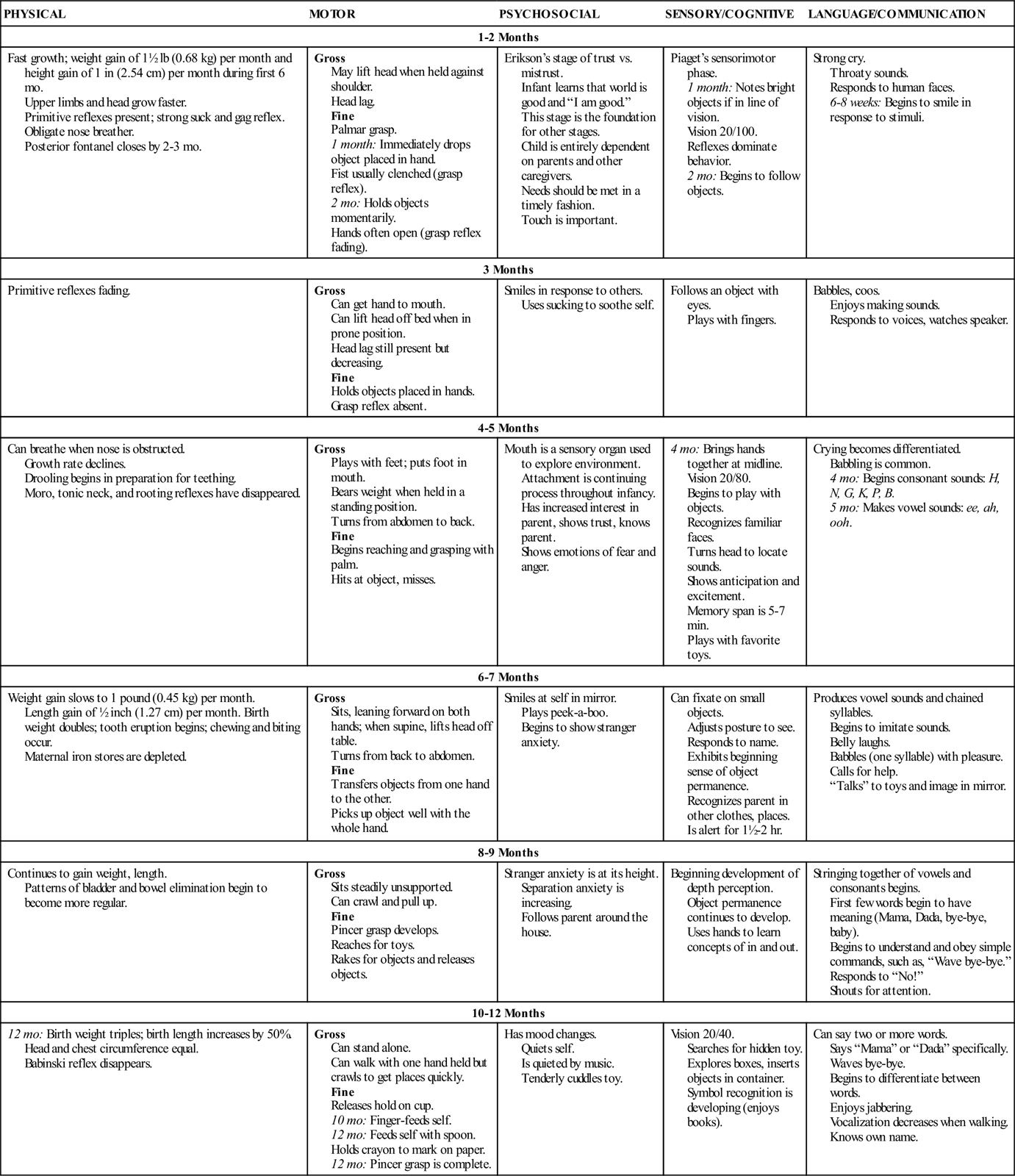

Providing parents with information about immunizations, feeding, sleep, hygiene, safety, and other common concerns is an important nursing responsibility. Appropriate anticipatory guidance can assist with achieving some of the goals and objectives determined by the U.S. government to be important in improving the overall health of infants. Nurses are in a good position to offer anticipatory guidance on the basis of the infant’s growth and achievement of developmental milestones. Table 6-1 summarizes growth and development during infancy.

TABLE 6-1

SUMMARY OF GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT: THE INFANT

| PHYSICAL | MOTOR | PSYCHOSOCIAL | SENSORY/COGNITIVE | LANGUAGE/COMMUNICATION |

| 1-2 Months | ||||

| Fast growth; weight gain of 1½ lb (0.68 kg) per month and height gain of 1 in (2.54 cm) per month during first 6 mo. Upper limbs and head grow faster. Primitive reflexes present; strong suck and gag reflex. Obligate nose breather. Posterior fontanel closes by 2-3 mo. | Gross May lift head when held against shoulder. Head lag. Fine Palmar grasp. 1 month: Immediately drops object placed in hand. Fist usually clenched (grasp reflex). 2 mo: Holds objects momentarily. Hands often open (grasp reflex fading). | Erikson’s stage of trust vs. mistrust. Infant learns that world is good and “I am good.” This stage is the foundation for other stages. Child is entirely dependent on parents and other caregivers. Needs should be met in a timely fashion. Touch is important. | Piaget’s sensorimotor phase. 1 month: Notes bright objects if in line of vision. Vision 20/100. Reflexes dominate behavior. 2 mo: Begins to follow objects. | Strong cry. Throaty sounds. Responds to human faces. 6-8 weeks: Begins to smile in response to stimuli. |

| 3 Months | ||||

| Primitive reflexes fading. | Gross Can get hand to mouth. Can lift head off bed when in prone position. Head lag still present but decreasing. Fine Holds objects placed in hands. Grasp reflex absent. | Smiles in response to others. Uses sucking to soothe self. | Follows an object with eyes. Plays with fingers. | Babbles, coos. Enjoys making sounds. Responds to voices, watches speaker. |

| 4-5 Months | ||||

| Can breathe when nose is obstructed. Growth rate declines. Drooling begins in preparation for teething. Moro, tonic neck, and rooting reflexes have disappeared. | Gross Plays with feet; puts foot in mouth. Bears weight when held in a standing position. Turns from abdomen to back. Fine Begins reaching and grasping with palm. Hits at object, misses. | Mouth is a sensory organ used to explore environment. Attachment is continuing process throughout infancy. Has increased interest in parent, shows trust, knows parent. Shows emotions of fear and anger. | 4 mo: Brings hands together at midline. Vision 20/80. Begins to play with objects. Recognizes familiar faces. Turns head to locate sounds. Shows anticipation and excitement. Memory span is 5-7 min. Plays with favorite toys. | Crying becomes differentiated. Babbling is common. 4 mo: Begins consonant sounds: H, N, G, K, P, B. 5 mo: Makes vowel sounds: ee, ah, ooh. |

| 6-7 Months | ||||

| Weight gain slows to 1 pound (0.45 kg) per month. Length gain of ½ inch (1.27 cm) per month. Birth weight doubles; tooth eruption begins; chewing and biting occur. Maternal iron stores are depleted. | Gross Sits, leaning forward on both hands; when supine, lifts head off table. Turns from back to abdomen. Fine Transfers objects from one hand to the other. Picks up object well with the whole hand. | Smiles at self in mirror. Plays peek-a-boo. Begins to show stranger anxiety. | Can fixate on small objects. Adjusts posture to see. Responds to name. Exhibits beginning sense of object permanence. Recognizes parent in other clothes, places. Is alert for 1½-2 hr. | Produces vowel sounds and chained syllables. Begins to imitate sounds. Belly laughs. Babbles (one syllable) with pleasure. Calls for help. “Talks” to toys and image in mirror. |

| 8-9 Months | ||||

| Continues to gain weight, length. Patterns of bladder and bowel elimination begin to become more regular. | Gross Sits steadily unsupported. Can crawl and pull up. Fine Pincer grasp develops. Reaches for toys. Rakes for objects and releases objects. | Stranger anxiety is at its height. Separation anxiety is increasing. Follows parent around the house. | Beginning development of depth perception. Object permanence continues to develop. Uses hands to learn concepts of in and out. | Stringing together of vowels and consonants begins. First few words begin to have meaning (Mama, Dada, bye-bye, baby). Begins to understand and obey simple commands, such as, “Wave bye-bye.” Responds to “No!” Shouts for attention. |

| 10-12 Months | ||||

| 12 mo: Birth weight triples; birth length increases by 50%. Head and chest circumference equal. Babinski reflex disappears. | Gross Can stand alone. Can walk with one hand held but crawls to get places quickly. Fine Releases hold on cup. 10 mo: Finger-feeds self. 12 mo: Feeds self with spoon. Holds crayon to mark on paper. 12 mo: Pincer grasp is complete. | Has mood changes. Quiets self. Is quieted by music. Tenderly cuddles toy. | Vision 20/40. Searches for hidden toy. Explores boxes, inserts objects in container. Symbol recognition is developing (enjoys books). | Can say two or more words. Says “Mama” or “Dada” specifically. Waves bye-bye. Begins to differentiate between words. Enjoys jabbering. Vocalization decreases when walking. Knows own name. |

Physical Growth and Maturation of Body Systems

Growth is an excellent indicator of overall health during infancy. Although growth rates are variable, infants usually double their birth weight by 6 months and triple it by 1 year of age. From an average birth weight of 7½ to 8 pounds (3.4 to 3.6 kg), neonates lose 10% of their body weight shortly after birth but regain birth weight by 2 weeks. During the first 5 to 6 months, the average weight gain is 1½ pounds (0.68 kg) per month. Throughout the next 6 months, the weight increase is approximately 1 pound (0.45 kg) per month. Weight gain in formula-fed infants is slightly greater than in breastfed infants.

During the first 6 months, infants increase their birth length by approximately 1 inch (2.54 cm) per month, slowing to ½ inch (1.27 cm) per month over the next 6 months. By 1 year of age, most infants have increased their birth length by 50%.

The head circumference growth rate during the first year is approximately 4⁄10 inch (1 cm) per month. Usually the posterior fontanel closes by 2 to 3 months of age, whereas the larger anterior fontanel may remain open until 18 months. Head circumference and fontanel measurements indicate brain growth and are obtained, along with height and weight, at each well-baby visit. Chapter 33 discusses growth-rate monitoring throughout infancy.

In addition to height and weight, organ systems grow and mature rapidly in the infant. Although body systems are developing rapidly, the infant’s organs differ from those of older children and adults in both structure and function. These differences place the infant at risk for problems that might not be expected in older individuals. For example, immature respiratory and immune systems place the infant at risk for a variety of infections, whereas an immature renal system increases risk for fluid and electrolyte imbalances. Knowledge of these differences provides the nurse with important rationales on which to base anticipatory guidance and specific nursing interventions.

Neurologic System

Brain growth and differentiation occur rapidly during the first year of life, and they depend on nutrition and the function of the other organ systems. At birth, the brain accounts for approximately 10% to 12% of body weight. By 1 year of age, the brain has doubled its weight, with a major growth spurt occurring between 15 and 20 weeks of age and another between 30 weeks and 1 year of age. Increases in the number of synapses and expanded myelinization of nerves contribute to maturation of the neurologic system during infancy. Primitive reflexes disappear as the cerebral cortex thickens and motor areas of the brain continue to develop, proceeding in a cephalocaudal pattern: arms first, then legs.

Respiratory System

In the first year of life, the lungs increase to three times their weight and six times their volume at birth. In the newborn infant, alveoli number approximately 20 million, increasing to the adult number of 300 million by age 8 years. During infancy, the trachea remains small, supported only by soft cartilage.

The diameter and length of the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles increase with age. These tiny, collapsible air passages, however, leave infants vulnerable to respiratory difficulties caused by infection or foreign bodies. The eustachian tube is short and relatively horizontal, increasing the risk for middle ear infections.

Cardiovascular System

The cardiovascular system undergoes dramatic changes in the transition from fetal to extrauterine circulation. Fetal shunts close, and pulmonary circulation increases drastically (see Chapter 46). During infancy, the heart doubles in size and weight, the heart rate gradually slows, and blood pressure increases.

Immune System

Transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies supplements the infant’s weak response to infection until approximately 3 to 4 months of age. Although the infant begins to produce immunoglobulins (Igs) soon after birth, by 1 year of age the infant has only approximately 60% of the adult IgG level, 75% of the adult IgM level, and 20% of the adult IgA level. Breast milk transmits additional IgA protection. The activity of T lymphocytes also increases after birth. Although the immune system matures during infancy, maximum protection against infection is not achieved until early childhood. This immaturity places the infant at risk for infection.

Gastrointestinal System

The stomach capacity of a neonate is approximately 10 to 20 mL, but with feedings the capacity increases rapidly to approximately 200 mL at 1 year of age. In the gastrointestinal system, enzymes needed for the digestion and absorption of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates mature and increase in concentration. Although the newborn infant’s gastrointestinal system is capable of digesting protein and lactase, the ability to digest and absorb fat does not reach adult levels until approximately 6 to 9 months of age.

Renal System

Kidney mass increases threefold during the first year of life. Although the glomeruli enlarge considerably during the first few months, the glomerular filtration rate remains low. Thus the kidney is not effective as a filtration organ or efficient in concentrating urine until after the first year of life. Because of the functional immaturity of the renal system, the infant is at great risk for fluid and electrolyte imbalance.

Motor Development

During the first few months after birth, muscle growth and weight gain allow for increased control of reflexes and more purposeful movement. At 1 month, movement occurs in a random fashion, with the fists tightly clenched. Because the neck musculature is weak, and the head is large, infants can lift their heads only briefly. By 2 to 3 months, infants can lift their heads 90 degrees from a prone position and can hold them steadily erect in a sitting position. During this time, active grasping gradually replaces reflexive grasping and increases in frequency as eye-hand coordination improves (see Table 6-1).

The Moro, tonic neck, and rooting reflexes disappear at approximately 3 to 4 months. These primitive reflexes, which are controlled by the midbrain, probably disappear because they are suppressed by growing cortical layers. Head control steadily increases during the third month. By the fourth month, the head remains in a straight line with the body when the infant is pulled to a sitting position. Most infants play with their feet by 4 to 5 months, drawing them up to suck on their toes. Parents need anticipatory guidance about ways to prevent unintentional injury by “baby-proofing” their homes before each motor development milestone is reached.

During the fifth and sixth months, motor development accelerates rapidly. Infants of this age readily reach for and grasp objects. They can bear weight when held in a standing position and can turn from abdomen to back. By 5 months, some infants rock back and forth as a precursor to crawling.

Six-month-old infants can sit alone, leaning forward on their hands (tripod sitting). This ability provides them with a wider view of the world and creates new ways to play. Infants of this age can roll from back to abdomen and can raise their heads from the table when supine. At 6 to 7 months, they transfer objects from one hand to the other. In addition, they can grab small objects with the whole hand and insert them into their mouths with lightning speed.

At 6 to 9 months, infants begin to explore the world by crawling. By 9 months, most infants have enough muscle strength and coordination to pull themselves up and cruise around furniture. These new methods of mobility enable the infant to follow a parent or caregiver around the house.

By 6 to 7 months, infants become increasingly adept at pointing to make their demands known. Six-month-old infants grasp objects with all their fingers in a raking motion, but 9-month-olds use their thumbs and forefingers in a fine motor skill called the pincer grasp. This grasp provides infants with a useful yet potentially dangerous ability to grab, hold, and insert tiny objects into their mouths.

Nine-month-old infants can wave bye-bye and clap their hands together. They can pick up objects but have difficulty releasing them on request. By 1 year of age, they can extend an object and release it into an offered hand. Most 1-year-old children can balance well enough to walk when holding another person’s hand. They often resort to crawling, however, as a more rapid and efficient way to move about.

An increased ability to move about, reach objects, and explore their world places infants at great risk for accidents and injury. Nurses provide information to parents about how quickly infant motor skills develop.

Cognitive Development

Many factors contribute to the way in which infants learn about their world. Besides innate intellectual aptitude and motivation, infants’ sensory capabilities, neuromuscular control, and perceptual skills all affect how their cognitive processes unfold during infancy and throughout life. In addition, variables such as the quality and quantity of parental interaction and environmental stimulation contribute to cognitive development.

Cognitive development during the first 2 years of life begins with a profound state of egocentrism. Egocentrism is the child’s complete self-absorption and the inability to view the world from anyone else’s vantage point (Piaget, 1952). As infants’ cognitive capacities expand, they become increasingly aware of the outside world and their separateness from it. Gradually, with maturation and experience, they become capable of differentiating themselves from others and their surroundings.

According to Piaget’s theory (1952), cognitive development occurs in stages or periods (see Chapter 5) as described in the following discussion. Infancy is included in the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), during which infants experience the world through their senses and their attempts to control the environment. Learning activities progress from simple reflex behavior to trial-and-error experiments.

During the first month of life, infants are in the first substage, reflex activity, of the sensorimotor period. In this substage, behavior such as grasping, sucking, or looking is dominated by reflexes. Piaget believed that infants organize their activity, survive, and adapt to their world by the use of reflexes.

Primary circular reactions dominate the second substage, occurring from age 1 to 4 months. During this substage, reflexes become more organized, and new schemata are acquired, usually centering on the infant’s body. Sensual activities such as sucking and kicking become less reflexive and more controlled and are repeated because of the stimulation they provide. The baby also begins to recognize objects, especially those that bring pleasure, such as the breast or bottle.

During the third substage, or the stage of secondary circular reactions, infants perform actions that are more oriented toward the world outside their own bodies. The 4- to 8-month-old infant in this substage begins to play with objects in the external environment, such as a rattle or stuffed toy. The infant’s actions are labeled secondary because they are intentional (repeated because of the response that is elicited). For example, a baby in this substage intentionally shakes a rattle to hear the sound.

By age 8 to 12 months, infants in the fourth substage, coordination of secondary schemata, begin to relate to objects as if they realize that the objects exist even when they are out of sight. This awareness is referred to as object permanence and is illustrated by a 9-month-old infant seeking a toy after it is hidden under a pillow. In contrast, 6-month-olds can follow the path of a toy that is dropped in front of them; however, they will not look for the dropped toy or protest its disappearance until they are older and have developed the concept of object permanence.

Infants in the fourth substage solve problems differently from how they solve problems in earlier substages. Rather than randomly selecting approaches to problems, they choose actions that were successful in the past. This tendency suggests that they remember and can perform some mental processing. They seem to be able to identify simple causal relationships, and they show definite intentionality. For example, when an 11-month-old child sees a toy that is beyond reach, the child uses the blanket that it is resting on to pull it closer (Flavell, 1964; Piaget, 1952).

Cognitive development in the infant parallels motor development. It appears that motor activity is necessary for cognitive development and that cognitive development is based on interaction with the environment, not simply maturation. Infancy is the period when the child lays the foundation for later cognitive functioning. Nurses can promote infants’ cognitive development by encouraging parents to interact with their infants and provide them with novel, interesting stimuli. At the same time, parents should maintain familiar, routine experiences through which their infants can develop a sense of security about the world. Within this type of environment, infants will thrive and learn.

Sensory Development

Vision

The size of the eye at birth is approximately one half to three fourths the size of the adult eye. Growth of the eye, including its internal structures, is rapid during the first year. As infants grow and become more interested in the environment, their eyes remain open for longer periods. They show a preference for familiar faces and are increasingly able to fixate on objects. Visual acuity is estimated at approximately 20/100 to 20/150 at birth but improves rapidly during infancy and toddlerhood. Infants show a preference for high-contrast colors, such as black and white and primary colors. Pastel colors are not easily distinguished until about 6 months of age.

Young infants may lack coordination of eye movements and extraocular muscle alignment but should achieve proper coordination by age 4 to 6 months. A persistent lack of eye muscle control beyond age 4 to 6 months needs further evaluation. Depth perception appears to begin at approximately 7 to 9 months and contributes to the infant’s new ability to move about independently (see Chapter 55).

Hearing

Hearing seems to be relatively acute, even at birth, as shown by reflexive generalized reactions to noise. With myelination of the auditory nerve tracts during the first year, responses to sound become increasingly more specialized. By 4 months, infants should turn their eyes and heads toward a sound coming from behind, and by 10 months infants should respond to the sound of their names. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (2007) has recommended that all newborn infants be screened for hearing impairment either as neonates or before 1 month of age and that those infants who fail newborn screening have an audiologic examination to verify hearing loss before age 3 months. The AAP also suggests that infants who demonstrate confirmed hearing loss be eligible for early intervention services and specialized hearing and language services as early as possible, but no later than 6 months of age (AAP, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2007). Newborn hearing screening generally is done before hospital discharge. Rescreening of both ears within 1 month of discharge is recommended for those newborns with questionable results. Additionally, screening should be available to those infants born at home or in an out-of-hospital birthing center (AAP, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2007).

Health providers should assess risk for hearing deficits at every well visit; any child who manifests one or more risks should have diagnostic audiology testing by age 24 to 30 months (Harlor & Bower, 2009). Risk factors include, but are not limited to, structural abnormalities of the ear, family history of hearing loss, pre- or postnatal infections known to contribute to hearing deficit, trauma, persistent otitis media, developmental delay, and parental concern (AAP Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2007). Harlor and Bower (2009) further recommend that referral for more complete testing and intervention be made for any child who fails an objective hearing screening, or whose parent expresses concerns about possible hearing loss.

Language Development

The acquisition of language has its roots in infancy as the child becomes increasingly intrigued with sound, begins to realize that words have meaning, and eventually uses simple sounds to communicate (Box 6-1). Although young infants probably understand tones and inflections of voice rather than words themselves, it is not long before repetition and practice of sounds enable them to understand and communicate with words. Infants can understand more than they can express.

The social smile develops early in the infant, usually by 3 to 5 weeks of age (Figure 6-1). This powerful communication tool helps to foster attachment and demonstrates that the infant can differentiate between people and objects within the environment. The infant who does not display a social smile by 8 to 12 weeks of age needs further evaluation and close follow-up because of the possibility of developmental delay.

During infancy, connections form within the central nervous system, providing fine motor control of the numerous muscles required for speech. Maturation of the mouth, jaw, and larynx; bone growth; and development of the face help prepare the infant to speak.

Vocalization, or speech, does not appear to be reflexive but rather is a relatively high-level activity similar to conversation. Parents usually elicit vocalization in infants better than other adults can. Language includes understanding word meanings, how to combine words into meaningful sentences and phrases, and social use of conversation. The development of both speech and language can be influenced by environmental cues, such as structures unique to a native language, physical disorders, hearing loss, cognitive impairment, autism spectrum disorders, or learning disabilities such as dyslexia (Schum, 2007).

Although there is great variability, most children begin to make nonmeaningful sounds, such as “ma,” “da,” or “ah,” by 4 to 6 months. The sounds become more meaningful and specific by 9 to 15 months, and by age 1 year the child usually has a vocabulary of several words, such as “mama,” “dada,” and “bye-bye.” Infants who have older siblings or who are raised in verbally rich environments sometimes meet these developmental milestones earlier than other infants.

Psychosocial Development

Most experts agree that infancy is a crucial period during which children develop the foundation of their personalities and their sense of self. According to Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development (1963), infants struggle to establish a sense of basic trust rather than a sense of basic mistrust in their world, their caregivers, and themselves. If provided with consistent, satisfying experiences delivered in a timely manner, infants come to rely on the fact that their needs will be met and that, in turn, they will be able to tolerate some degree of frustration and discomfort until those needs are met. This sense of confidence is an early form of trust and provides the foundation for a healthy personality.

Conversely, if infants’ needs are ignored or met in a consistently haphazard, inadequate manner, they have no reason to believe that their needs will be met or that their environment is a safe, secure place. According to Erikson, without consistent satisfaction of needs, the individual develops a basic sense of suspicion or mistrust (Erikson, 1963).

Parallel to this viewpoint is Freudian theory, which regards infancy as the oral stage (Freud, 1974). The mouth is the major focus during this stage. Observation of infants for a few minutes shows that most of their behavior centers on their mouths. Sensory stimulation and pleasure, as well as nourishment, are experienced through their mouths. Sucking is an adaptive behavior that provides comfort and satisfaction while enabling infants to experience and explore their world. Later in infancy, as teething progresses, the mouth becomes an effective tool for aggressive behavior (see Chapter 7).

Parent-Infant Attachment

One of the most important aspects of infant psychosocial development is parent-infant attachment. Attachment is a sense of belonging to or connection with each other. This significant bond between infant and parent is critical to normal development and even survival. Initiated immediately after birth, attachment is strengthened by many mutually satisfying interactions between the parents and the infant throughout the first months of life.

For example, noisy distress in infants signals a need, such as hunger. Parents respond by providing food. In turn, infants respond by quieting and accepting nourishment. The infants derive pleasure from having their hunger satiated and the parents from successfully caring for their children. A basic reciprocal cycle is set in motion in which parents learn to regulate infant feeding, sleep, and activity through a series of interactions. These interactions include rocking, touching, talking, smiling, and singing. The infants respond by quieting, eating, watching, smiling, or sleeping.

Conversely, continuing inability or unwillingness of parents to meet the dependency needs of their infants fosters insecurity and dissatisfaction in the infants. A cycle of dissatisfaction is established in which parents become frustrated as caregivers and have further difficulty providing for the infant’s needs.

If parents can adapt to their infant, meet the infant’s needs, and provide nurturance, attachment is secure. Psychosocial development can proceed on the basis of a strong foundation of attachment. Conversely, if parents’ personalities and abilities to cope with infant care do not match their infant’s needs, the relationship is considered at risk.

Although the establishment of trust depends heavily on the quality of the parental interaction, the infant also needs consistent, satisfying social interactions within a family structure. Family routines can help to provide this consistency. Touch is an important tool that can be used by all family members to convey a sense of caring.

Stranger Anxiety

Another important aspect of psychosocial development is stranger anxiety. By 6 to 7 months, expanding cognitive capacities and strong feelings of attachment enable infants to differentiate between caregivers and strangers and to be wary of the latter. Infants display an obvious preference for parents over other caregivers and other unfamiliar people. Anxiety, demonstrated by crying, clinging, and turning away from the stranger, is manifested when separation occurs. This behavior peaks at approximately 7 to 9 months and again during toddlerhood, when separation may be difficult (see Chapter 7).

Although stressful for parents, stranger anxiety is a normal sign of healthy attachment and occurs because of cognitive development (object permanence). Nurses can reassure parents that, although their infants seem distressed, leaving the infant for short periods does no harm. Separations should be accomplished swiftly, yet with care, love, and emphasis on the parents’ return.

Health Promotion for the Infant and Family

Parents, particularly new parents, often need guidance in caring for their infant. Nurses can provide valuable information about health promotion for the infant. Specific guidance about everyday concerns, such as sleeping, crying, and feeding, can be offered, as well as anticipatory guidance about injury prevention. An important nursing responsibility is to provide parents with information about immunizations and dental care. Nurses can offer support to new parents by identifying strategies for coping with the first few months with an infant. The schedule of well visits corresponds with the schedule recommended by the AAP. At each well visit the nurse assesses development, administers appropriate immunizations, and provides anticipatory guidance. The nurse asks the parent a series of general assessment questions (Box 6-2) and then focuses the assessment on the individual infant.

Immunization

The importance of childhood immunization against disease cannot be overemphasized. Infants are especially vulnerable to infectious disease because their immune systems are immature. Term neonates are protected from certain infections by transplacental passive immunity from their mothers. Breastfed infants receive additional immunoglobulins against many types of viruses and bacteria. Transplacental immunity is effective only for approximately 3 months, however, and for a variety of reasons, many mothers choose not to breastfeed. In any case, this passive immunity does not cover all diseases, and infection in the infant can be devastating. Immunization offers protection that all infants need.

Nurses play an important role in health promotion and disease prevention related to immunization. Nursing responsibilities include assessing current immunization status, removing barriers to receiving immunizations, tracking immunization records, providing parent education, and recognizing contraindications to the receipt of vaccines. Chapter 5 provides detailed information regarding immunizations and their schedule.

Feeding and Nutrition

Because infancy is a period of rapid growth, nutritional needs are of special significance. During infancy, eating progresses from a principally reflex activity to relatively sophisticated, yet messy, attempts at self-feeding. Because the infant’s gastrointestinal system continues to mature throughout the first year, changes in diet, the introduction of new foods, and even upsets in routines can result in feeding problems.

Parents often have many questions and concerns about nutrition. They are influenced by a variety of sources, including relatives and friends who may not be aware of current scientific practices regarding infant feeding. To provide anticipatory guidance, the nurse must have a clear understanding of gastrointestinal maturation and knowledge about breastfeeding and various infant formulas and foods. Families and cultures vary widely in food preferences and infant feeding practices. The nurse must remain cognizant of these differences when providing anticipatory guidance related to infant nutrition.

Factors Influencing Choice of Feeding Method

The AAP strongly recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life for all infants, including premature and sick newborns, with rare exceptions (AAP, 2012). Increasing the percentage of infants who are exclusively breastfed is a goal of Healthy People 2020. Although 74% of infants in the United States are breastfed at birth, only 43.5% of infants in the United States breastfeed for 6 months, and that percentage goes down to 22% breastfeeding at 1 year (United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010). The percentage of infants who are breastfed exclusively at 6 months is only 14.1%.

Breastfeeding

Breast milk provides complete nutrition for infants, and evidence suggests that breastfed infants are less likely to be at risk for later overweight or obesity (Huh, Rifas-Shiman, Taveras, et al., 2011). A recent meta-analysis of 18 case control studies provides high-level evidence that the odds of a breastfed infant dying of SIDS are far lower than those of infants never given breast milk, and that the protection is even stronger for infants who are exclusively breastfed (Hauck, Thompson, Tanabe, et al., 2011).

Mothers who breastfeed need instruction and support as they begin. They are more likely to succeed if they are given practical information. Many facilities provide lactation consultants or home visits, or nursing staff may call to assess the mother’s needs. Significant others are included in teaching to provide a support system for the mother. Breastfed infants need to receive vitamin D supplementation to prevent the occurrence of rickets. Breastfed infants may also need iron supplementation. The AAP (Greer, Sicherer, Burks, & the Committee on Nutrition and Section on Allergy and Immunology, 2008) recommends vitamin D supplementation of 400 IU/day for all breastfed and partially breastfed infants and for formula-fed infants who consume less than 1 L (33 oz) of vitamin D–fortified formula a day. An in-depth discussion of breastfeeding can be found in Chapter 23.

Formula Feeding

Formula given by bottle is a choice selected by many women in the United States. This method is often easier for the mother who must return to work soon after her infant’s birth, and it has the advantage of allowing other members of the family to participate in the infant’s feeding. Infant formula does not have the immunologic properties and digestibility of human milk, but it does meet the energy and nutrient requirements of infants. If bottle feeding is chosen as the preferred feeding method, the formula should be iron fortified. The Infant Formula Act of 1980, which was revised in 1986, establishes the standards for infant formulas. It also requires that the label show the quantity of each nutrient contained in the formula. Special formulas are available for low-birth-weight infants, infants with congenital cardiac disease, and for infants allergic to cow’s milk–based formulas.

There are some physiologic reasons why some mothers choose to use formula. Infants with galactosemia or whose mothers use illegal drugs, are taking certain prescribed drugs (e.g., antiretrovirals, certain chemotherapeutic agents), or have untreated active tuberculosis should not be breastfed (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009). In the United States and other countries where safe water is available, even if breastfeeding is culturally acceptable, women who are infected with HIV should avoid breastfeeding (AAP, 2009).

Types of Formula

Formula can be purchased in three different forms—ready-to-use, concentrated liquid, and powdered. With the exception of the ready-to-use formula, all need to have water added to obtain the appropriate concentration for feeding. Storage instructions differ, so nurses need to strongly encourage parents to carefully follow the directions for storage of the specific type of formula they are using for their infant.

Although commercially prepared formulas have many similarities, there are also differences. Some commonly used brands are Enfamil, SMA, Similac, Gerber, and Good Start. There are formulas specifically designed for infants older than 6 months, but it is not necessary to change to a different formula when a child reaches that age. Some formulas are designed for feeding low-birth-weight or ill infants. These include high-calorie formulas and predigested formulas (e.g., Pregestimil, Nutramigen).

Cow’s Milk

Cow’s milk (whole, skim, 1%, 2%) is not recommended in the first 12 months. Cow’s milk contains too little iron, and its high renal solute load and unmodified derivatives can put small infants at risk for dehydration. The tough,