Health Promotion During Early Childhood

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Provide parents with anticipatory guidance related to the toddler and preschooler.

• Identify strategies to alleviate a preschool child’s fears and sleep problems.

• Discuss strategies for disciplining a toddler and a preschooler.

• Describe signs of a toddler’s readiness for toilet training, and offer guidelines to parents.

• Offer parents suggestions for promoting school readiness in the preschool child.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

The developmental changes that mark the transition from infancy to early childhood are dramatic. During the toddler years, ages 12 through 36 months, the child begins to venture out independently from a secure base of trust established during the first year. The preschool period, ages 3 through 5 years, is a time of relative tranquility after the tumultuous toddler period.

Growth and Development During Early Childhood

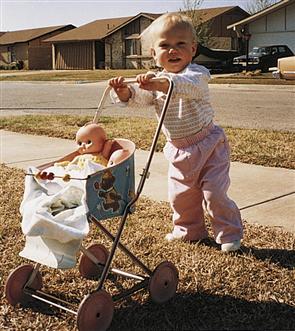

The toddler years are characterized by a struggle for autonomy as the child develops a sense of self separate from the parent. Boundless energy and insatiable curiosity drive the toddler to explore the environment and master new skills (Figure 7-1). The combination of increased motor skills, immaturity, and lack of experience places the toddler at risk for unintentional injury. Toddlers’ egocentric and demanding behaviors, often marked by temper tantrums and negativism, have given this age the label the “terrible twos.”

The toddler is enchanted by a world filled with discovery. Curiosity provides resources for the tremendous cognitive growth that occurs during this period. Pots and pans are popular toys for inquisitive toddlers. However, exploring cupboards can be a dangerous activity for toddlers. Toxic cleaning substances and other dangerous objects must be kept behind locked doors and out of reach. Reading simple stories provides quiet, enjoyable times for toddlers and parents and enhances speech and language development.©2012 Photos.com, a division of Getty Images. All rights reserved. Toddlers enjoy push-pull toys. Toys should be strong and sturdy; wheeled toys should not tip over easily.

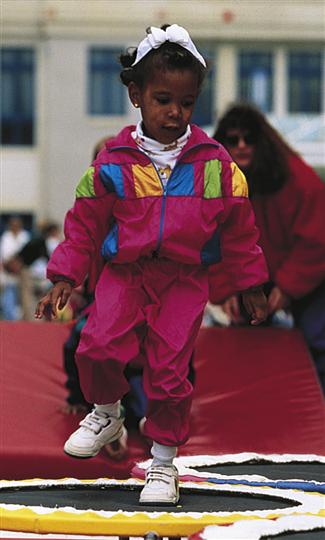

The preschooler becomes increasingly independent, mastering many self-care and motor skills and developing greater social and emotional maturity (Figure 7-2). The preschooler is imaginative, creative, and curious. Many parents describe this period as their favorite age as they watch the dramatic transformation of a chubby toddler into an agile, articulate child who is ready to enter the world of peers and school.

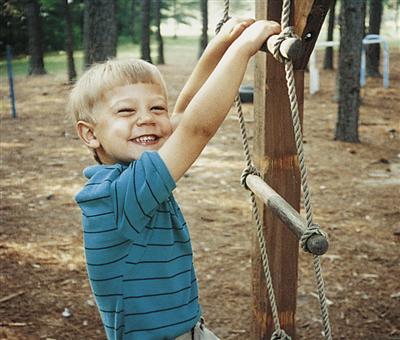

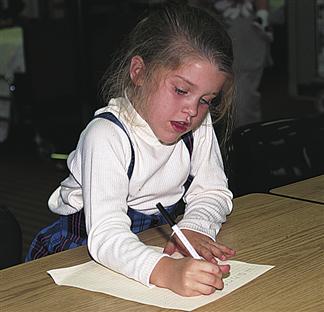

As the brain matures, the preschool child’s motor development matures. Opportunities for practice contribute to the development of motor skills. (Courtesy Cook Children’s Medical Center, Fort Worth, TX.) This 4-year-old’s motor development has increased to the point that he can jump and climb well. A 4-year-old can also throw a ball overhand and cut on a curved line with scissors. This 5-year-old is printing her name in readable letters. Children of this age can usually skip and can both throw and catch a ball. (Courtesy University of Texas at Arlington School of Nursing, Arlington, TX.)

The nurse’s roles as health care provider, family counselor, and child advocate continue during the toddler and preschool years. Well-child checkups provide the nurse with opportunities for anticipatory guidance related to growth and development, safety, nutrition, and some of the common age-related concerns of parents. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (2006/2010) recommends that pediatric providers conduct developmental surveillance (assessing developmental milestones and determining risk for developmental delay) at every routine well visit and that formal developmental screening, using a sensitive and specific screening test, be done at the 9-, 18-, and 30- (or 24-) month visits. In addition, an autism-specific screening should be done at the 18-month visit (AAP, 2006/2010). Because parental concerns provide a reliable indicator of possible developmental delay, the nurse should elicit any concerns when taking a developmental history as part of every well visit.

Physical Growth and Development

The Toddler

Physical growth slows during the toddler years. The average weight gain is 2.25 kg (5 lb) per year. A child’s birth weight has quadrupled by age 2 to 3 years. The rate of increase in height also slows, with the average toddler growing approximately 7.5 cm (3 inches) per year.

The brain grows at a slower rate during this period than during infancy. Head circumference reflects this growth, increasing approximately 3.7 cm (1½ inches) during the toddler years compared with the growth of 12 cm (44⁄5 inches) in the first 12 months. By age 2 years, the head circumference has reached 90% of its adult size.

Immature abdominal musculature gives the toddler a potbellied appearance, with an exaggerated lumbar curve. The child’s short legs may appear slightly bowed, and the feet seem flat because of a plantar fat pad that disappears around age 2 years. During the toddler years, muscle tissue gradually replaces much of the adipose tissue (baby fat) present during infancy. As the musculoskeletal system matures and the child walks and runs more, the cherubic toddler disappears, and the child grows into a taller, leaner preschooler.

The Preschooler

The preschool child’s growth is slow and steady. Height and weight gains are minimal during this period. The average weight gain is approximately 2.25 kg (5 lb) per year, and the height gain averages 5 to 7.5 cm (2 to 3 inches) per year. Children attain half their adult height between ages 2 and 3 years. During this time, growth occurs more rapidly in the legs than in the trunk, accumulation of adipose tissue declines, and the child’s appetite decreases. As a result, the preschooler loses

the potbellied appearance of the toddler, becoming slimmer and more agile. Muscles grow faster than bones during the preschool period. Muscle strength is influenced by nutrition, genetic makeup, and the opportunity to exercise and use the muscles. Knock-knees (see Chapter 50) are common in 3-year-olds and are often associated with occasional stumbling and falling. Maturation of the knee and hip joints usually corrects this problem by age 4 or 5 years.

As the lungs grow, the vital capacity increases, and the respiratory rate slows. Respirations remain primarily diaphragmatic until age 5 or 6 years. The heart rate decreases, and the blood pressure rises as the heart increases in size (see Chapter 33 for vital sign ranges). Cardiovascular maturation enables the preschooler to engage in more sustained and strenuous activity.

All 20 deciduous teeth are present by age 3 years. Deciduous teeth may begin to fall out at the end of the preschool period. The first permanent teeth to erupt, the back molars, usually appear in the early school-age years.

Motor Development

The Toddler

Learning to walk well is the crowning achievement of the toddler period. The child is in perpetual motion, seemingly compelled to pull up, take a few steps, fall, and repeat the process over and over, oblivious to bumps and bruises. The toddler will repeat this performance hundreds of times until the skill of walking has been perfected.

The age at which children learn to walk varies widely. Most children can walk alone by 15 months. By 18 months of age, toddlers walk well and try to run but fall often. At approximately 15 months of age, many toddlers become avid climbers. Chairs, tables, and bookcases all present irresistible challenges and risks for injury. Parents may have difficulty keeping the toddler in a crib and may decide to move the child to a regular bed.

Toddlers are also engaged in perfecting fine motor skills. Hand-eye coordination improves with maturity and practice. Mealtimes are still messy. Although most 18-month-olds can hold a cup with both hands and drink from it without much spilling, eating with a spoon is difficult. Most of the food conveyed in a spoon is spilled. Children need a great deal of practice with a spoon before they can feed themselves without spilling. Most toddlers can feed themselves with a spoon by their second birthday if they have been allowed to practice.

At 18 months of age, the toddler enjoys removing clothing. By 24 months, the toddler can put on simple items of clothing but cannot differentiate front from back. Children at this age also can zip large zippers, put on shoes, and wash and dry their hands. Two-year-olds brush their teeth but need help in adequately removing plaque.

The toddler’s increasing motor skills allow more independence in all areas of daily life. Feeding, dressing, and play provide opportunities for the child to develop autonomy. Motor development in this age-group is far ahead of development of judgment and perception. This difference in timing of the development of different skills increases the risk for injury.

The Preschooler

Coordination and muscle strength increase rapidly between ages 3 and 5 years. Increases in brain size and nerve myelinization enable the child to perfect fine and gross motor skills.

Motor abilities vary widely among children. Although motor skill is less influenced by environment than other areas of development, such as language, opportunities to practice may contribute to better motor skills. For example, a 4-year-old who often plays catch with a sibling or parent generally finds playing Little League baseball as a 7-year-old easier than a child without a similar experience.

Handedness begins to emerge at approximately 3 years and is usually clearly established by 4 years. The nurse should encourage parents to provide left-handed children with appropriate tools, particularly left-handed scissors. Left-handed children should not be forced to use their right hands because coordination is usually better when they use the dominant side. Eye-hand coordination is usually good enough by age 5 years for a child to hit a nail on the head with a hammer. Increased coordination allows the child to perform many self-care skills and become more independent.

By age 4 or 5 years, the child is independent and can dress, eat, and go to the bathroom without help. Unlike the toddler, who must be restrained to avoid injury, the older preschooler can usually be trusted to heed verbal warnings of danger.

Cognitive and Sensory Development

The Toddler

Toddlers are consumed with curiosity. Their boundless energy and insatiable inquisitiveness provide them with resources for the tremendous cognitive growth that occurs during this period.

Toddlers between ages 12 and 18 months are in Piaget’s sensorimotor period (Piaget, 1952) (see Chapter 5) . Learning in this stage occurs mainly by trial and error. Toddlers spend most of a busy day experimenting to see what will happen as they dump, fill, empty, and explore every accessible area of their environment. Between 19 and 24 months, the child enters the final stage of the sensorimotor period. Object permanence is firmly established by this age. The child has a beginning ability to use symbols and words when referring to absent people or objects and begins to solve problems mentally rather than by repeating an action over and over. A toddler at this stage is often seen imitating the parent of the same sex performing household tasks (termed domestic mimicry). Late in this stage, the child displays deferred imitation (e.g., imitating the parent putting on makeup or shaving hours after that parent has left for work). The 18-month-old has a beginning ability to wait, as evidenced by appropriate response of the toddler to a parent or caregiver who says “just a minute.” The child’s concept of time is still immature, however, and “a minute” may seem like an hour to the toddler.

Toddlers think in terms of the predictable routines of their daily schedule. When talking with the toddler, the nurse should use time orientation in relation to familiar activities. For example, a toddler understands “Your mother will be here after your nap” better than “Your mother will be here at 2 o’clock.”

Many hours each day are spent putting objects into holes and smaller objects into each other as the child experiments with sizes, shapes, and spatial relations. Toddlers enjoy opening drawers and doors, exploring the contents of cabinets and closets, and generally wreaking havoc throughout the house, as well as exposing themselves to potential danger.

According to Piaget (1952), the preoperational stage of cognitive development characterizes the second half of early childhood (see Chapter 5). This stage is divided into two phases: the preconceptual phase (2 to 4 years) and the intuitive phase (4 to 7 years). During the preconceptual phase, the child is beginning to use symbolic thought—the ability to allow a mental image (words or ideas) to represent objects or ideas. Mental symbols allow the child to remember the past and describe events that happened in the past. At approximately 24 months, children enter the preconceptual phase, which ends at age 4 years. In this phase, children begin to think and reason at a primitive level. Two-year-olds have a beginning ability to retain mental images. This ability allows them to internalize what they see and experience. Symbols in the form of words can be used to represent ideas. Increasing amounts of play time are spent pretending. A box may become a spaceship or a hat; pebbles may be money or popcorn. The child’s rapidly growing vocabulary enhances symbolic play. The toddler begins to think about alternative solutions to a problem and can even consider the consequences of an action without carrying it out (touching a hot stove, running too fast on a slippery sidewalk).

The toddler’s thinking is immature, limited in its logic, and bound to the present. Egocentrism, animism, irreversibility, magical thinking, and centration characterize the preoperational thought of the toddler (Table 7-1). The predominant words in the toddler’s language repertoire are “me,” “I,” and “mine.”

TABLE 7-1

Characteristics of Preoperational Thinking

| CHARACTERISTIC | EXAMPLE |

| Egocentrism: Views everything in relation to self; is unable to consider another’s point of view. | Toddler takes a toy away from another child and cannot understand that the other child wants (or has a right to) the toy, too. |

| Animism: Believes that inert objects are alive and have wills of their own. | Toddler trips over a toy and scolds the toy for hurting her. She believes that the toy hurt her on purpose. |

| Irreversibility: Cannot see a process in reverse order. Cannot follow a line of reasoning back to its beginning. Cannot hold onto two or more sequential thoughts simultaneously. | If the child takes a toy apart, the child cannot remember the sequence for putting it back together. If a child is taken on a walk, the child cannot retrace steps and find the way home. |

| Magical thought: Believes that magical thought is the cause of events and that wishing something will make it so. | Toddlers often feel extremely powerful and believe that their thoughts cause events to happen. |

| Centration: Tends to focus on only one aspect of an experience, ignoring other possible alternatives. Focuses on the dominant characteristic of an object, excluding other characteristics. | May have difficulty putting together a puzzle, concentrating on only one detail of a piece (e.g., shape) and ignoring other qualities (e.g., color, detail). Cannot follow more than one direction at a time. |

The Preschooler

By age 3 years, the brain has reached two thirds of its adult size. Maturation of the central nervous system contributes to the child’s increasing cognitive abilities.

The 3-year-old can retain a mental image of a loved one and can periodically “refuel” by thinking about that person. A photograph can help some children cope with separation by bridging the gap between physical presence and mental image. Preschoolers’ ability to remember their parents and recognize that their needs can be met even though their parents are not present enhances their ability to tolerate separation.

Because preschoolers still engage in animism, they often endow inanimate objects with lifelike qualities during play. A doll may become a crying baby, or a teddy bear may become a friend who listens sympathetically. Symbolic play is important for emotional development because it allows the child to work through distressing feelings. For this reason, allowing a child to play with medical equipment after a painful procedure can be therapeutic. Four-year-olds who have received injections may be found working out their feelings by giving their dolls “lots of shots.”

During the preconceptual phase, reality may be distorted by transductive reasoning. The preschool child reasons from particular to particular rather than from particular to general, and vice versa, as adults do. The child cannot understand that relationships exist and cannot view the whole in relation to its parts. The preschool child has difficulty focusing on the important aspects of a situation. To a child, everything is important

and interdependent. This type of thinking is called field dependency. For example, the preschooler may have difficulty falling asleep at night because the parent did not follow the usual bedtime routine. Objects, routine, and sameness are important to the preschool child. Rituals provide the preschool child with a feeling of control.

The second phase of Piaget’s preoperational stage, the intuitive phase, is characterized by centration and lack of reversibility. Centration is the tendency to center or focus on one part of a situation and ignore the other parts. The child cannot understand logical relationships and is unable to focus on more than one aspect of a situation at a time. For example, the child may not be able to follow a sequence of directions but will perform well if the directions are given one at a time.

The 4- or 5-year-old shows irreversibility in thought (Piaget, 1952). Children this age cannot reverse a process or the order of events. They may be able to take a complex puzzle apart but have difficulty putting it back together. The 4- or 5-year-old also lacks reversibility for mathematical processes. The child may be able to add 3 and 1 and get 4, but reversing the problem (4 − 1 = 3) would be too difficult.

The preschool years are a period of rapid learning. The preschool child is curious and wants to know how things work. Preschoolers’ thinking is still magical and egocentric (focused on the self). Children at this age tend to understand events only as these events affect them, believing that everyone else has had the same experience. Children seeing their mother in distress may bring her a doll, assuming that it would comfort the mother as it does the child.

Preschool children often think that their thoughts are powerful enough to cause things to happen. They may frighten themselves with some of their ideas, believing that they may become what they imagine they will be. Preschoolers may feel overwhelmed by guilt when a sibling is hospitalized because they believe that their hostile feelings caused the sibling’s illness. Likewise, a child of this age may say, “I got sick because I was bad.”

Language Development

The Toddler

The acquisition of language is one of the most dramatic developments of early childhood. Although the age at which children begin to talk varies widely, most can communicate verbally by their second birthday. The rate of language development depends on physical maturity and the amount of reinforcement that the child has received. Between 15 and 24 months of age, language ability develops rapidly. Toddlers understand many more words than they can say because receptive language (what the child understands) develops earlier and more quickly than speech. Sometime after 18 months, many children experience a sudden spurt in speech production and comprehension, resulting in a vocabulary of 300 or more words at 24 months. By 2 years of age, roughly 60% to 70% of toddlers’ speech should be understandable. Because children age 24 to 30 months are less egocentric and better able to consider another’s point of view, they engage in more conversation with others and less monologue.

The standardized developmental screening recommended by the AAP to occur at age 18 months is designed to identify children with communication delay (AAP, 2006/2010). If language development is not progressing normally, parents should be advised to pursue follow-up care. Children of bilingual families, children who are twins, and children other than first-borns may have slower language development. Because language development depends on adequate hearing, delayed language can be seen in children who have had repeated ear infections or who have undiagnosed hearing loss (see Chapter 55).

Parents can promote language development by talking to their children and incorporating teaching into daily routines. Feeding, bathing, dressing, and going on outings to both new and familiar places offer opportunities for verbal interaction and the practice of growing language skills. The child should be encouraged to express needs rather than have the parent anticipate and provide what the child wants before the child asks for it. Reading simple, entertaining stories with colorful pictures provides quiet, enjoyable times for toddlers and parents and enhances speech and language development.

The Preschooler

A dramatic increase in language skill in the preschool period promotes self-control and increases the child’s ability to direct and be directed by others. Children at this age may be heard talking to themselves about things they have heard or been taught.

The preschooler’s vocabulary increases rapidly, from 300 words at 2 years of age to more than 2100 words at 5 years. In less than 3 years, the child grows from a toddler who knows only a few words into a child who skillfully uses an extensive vocabulary to describe events, share feelings, and ask questions. Three-year-olds speak in short, telegraphic sentences. They may talk to themselves or to imaginary friends. A delightful characteristic of young preschoolers is the tendency to engage in lengthy monologues, regardless of whether anyone is listening or even present. Such self-talk provides the child with opportunities to practice speech and is often accompanied by symbolic play.

By 4 years old, children talk incessantly and tend to boast and exaggerate. They enjoy rhymes and silly ways to use similar words. Four-year-olds expect more detailed answers to their questions. They may use speech aggressively and may use profanity to gain attention. “Bad” language should be ignored, thus depriving the child of reinforcement of the behavior. When children feel that they gain power over their parents by using bad language, these verbalizations will continue.

Five-year-olds speak in sentences of adult length and use all parts of speech. They usually are proficient storytellers who produce elaborate tales for anyone who will listen. Their tendency to mix fantasy with reality may be perceived by adults as lying. The child of 5 years usually can recite the days of the week and can name the seasons.

Nurses can teach parents strategies to promote their child’s language development. It is important for parents to talk with the child and respond to the child’s attempts at communication. Reading to the child and making reading materials available can help build vocabulary and promote a lifelong love of reading. Watching educational television programs with their child may augment parents’ communication skills with their child. Preschoolers spend a lot of time asking “how” and “why” questions, often taxing parents’ patience. Short, simple, honest answers encourage vocabulary building and boost self-esteem.

Psychosocial Development

The Toddler

The toddler is developing a sense of autonomy, giving up the comfort of dependence enjoyed during infancy. If a basic sense of trust was established during the first year, the toddler can venture forward and separate from parents for short periods to explore and experience the world.

According to Erikson (1963), the toddler is struggling with the developmental task of acquiring a sense of autonomy while overcoming a sense of shame and doubt. Toddlers discover that they have a will of their own and that they can control others. Asserting their will and insisting on their own way, however, often lead to conflict with those they love, whereas submissive behavior is rewarded with affection and approval. Toddlers experience conflict because they want to assert their own will but do not want to risk losing the approval of loved ones. If the child continues to practice dependent behavior, doubt related to abilities develops. Toddlers may feel shame for independent impulses, particularly if frequent punishment is associated with their actions.

The toddler learns which behaviors gain approval and which result in censure and punishment. Two-year-olds do not have a conscience but avoid punishment by controlling their behavior. Right and wrong are determined by the consequences of actions.

At approximately 15 months, toddlers begin to demonstrate their developing autonomy with two almost universal behaviors: negativism and ritualism.

Negativism

Negativism, one of the most dramatic expressions of independence, is shown in a variety of ways. The toddler’s favorite word seems to be “no.” Unable to distinguish between requests and directives, the toddler seems to believe that saying “yes” would mean giving up free will. The child often seems to delight in this test of wills with the parent. Negativism may result in screaming, kicking, hitting, biting, or breath-holding. Parents often interpret the child’s negative behavior as being bad or stubborn. Nurses can help parents understand their toddler’s behavior as an important sign of the child’s progress from dependence to autonomy and independence. The nurse should give support and encourage the parent to deal with the toddler’s trying behavior with patience and a sense of humor. Although general permissiveness is not recommended, too much pressure and forceful methods of control often lead to defiance, tantrums, and prolonged negative behavior.

Ritualism and the Importance of Routine

Ritualism helps the child venture out and away from the safety of the parents by ensuring uniformity and security. Ritualism allows the toddler to have a sense of control. The child feels more confident with a secure home base. The toddler insists on sameness. Milk may have to be poured into the same cup, parents may have to sit in the same chairs at dinnertime, and a specified routine may have to be followed countless times throughout the day. The child may be unable to go to sleep unless a bedtime ritual is followed exactly (e.g., a drink of water, two stories, prayers, and a teddy bear). The child may experience distress if this routine is not followed exactly the next night. Failure to recognize the importance of such rituals may increase stress and insecurity.

Events such as hospitalization, during which continuity of routine cannot be ensured, are difficult for the toddler. The nurse can decrease the stress of hospitalization by incorporating the child’s usual rituals and routines from home into nursing care activities. Keeping hospital routines as similar to those of home as possible and recognizing ritualistic needs give the toddler some sense of control and security and reduce feelings of helplessness and fear. See Chapter 35 for further discussion of the hospitalized child.

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety peaks again in the toddler period. Although the concept of object permanence is fully developed in the toddler, children at this stage have difficulty differentiating their own feelings from those of their parents. Although the children experience a strong desire to be independent and leave their mothers, they fear that their mothers also want to leave them. A toddler may strike out independently across the room, only to rush back in tears to the mother, as if the child were frightened and angry with the mother for leaving. For a brief period, the parent may find talking on the telephone without interruption or even going into the bathroom without being followed virtually impossible. Leave-taking and brief separations are acceptable to a toddler if they are the toddler’s idea, but the parent’s departure may cause desperate clinging and crying. Games such as hide-and-seek help the child master fears of separation. Repeating separation under conditions the child can control helps the toddler overcome the anxiety associated with separation. The child learns from experience that loved ones will return after separation.

Being left with a stranger can be stressful. Toddlers should be told honestly and clearly about a separation shortly before it occurs. The parent or nurse should reassure the child that the parent is coming back. When the parent returns, the toddler often shows anger at being left by ignoring the parent or by pretending to be more interested in play than in going home. Parents of hospitalized toddlers are frequently distressed by such behavior when they visit their child (see Chapter 35).

Tolerating brief separations from parents is an important developmental task for the toddler. Transition objects, such as a favorite blanket or toy, provide comfort to the toddler in stressful situations, such as separation, illness, and even bedtime. Such objects help children make the transition from dependency to autonomy. Toddlers may become so attached to an object that they can hardly bear to part with it, even for a brief time while it is being laundered.

The nurse can offer support by explaining that the behavior is a normal growth and development milestone and telling the parents that plenty of affection and attention are needed to help the toddler cope with the stress of separation. The nurse counsels parents to leave a toddler only briefly at first and, if possible, to delay extended separations until the toddler can handle them better. The nurse who helps parents understand normal toddler behavior in response to separation helps parents cope with the frustrations of this transition.

Play

Toddlers spend most of their time at play. Play is serious business to the toddler—it is the child’s work. Many hours are spent each day in play, perfecting fine and gross motor skills, learning to control inner urges, and gaining self-esteem. Play during this period reflects the egocentric toddler’s developmental level. The toddler engages in parallel play, in which children play alongside but not with other children (Figure 7-3). Little regard is given to the feelings of others. Children engaged in this type of play frequently grab toys away from other children or may hit or fight to obtain a wanted toy. Because toddlers are egocentric, they do not realize that they are hurting the other child and feel no shame for aggressive actions.

Parallel play occurs when children play side by side with similar toys but no organized group activity occurs. The children play beside one another but not with one another. (Courtesy University of Texas at Arlington School of Nursing, Arlington, TX.) Symbolic play consists of activities that children use to express their perception of reality. This little girl is acting out a familiar adult scenario as she manipulates child-size toys that represent kitchen equipment.

Imitation and acting out scenes of everyday life are common as the toddler begins to try out roles and identify with adults. Active, large-muscle play helps the toddler vent frustrations and dissipate excess energy. The nurse can help parents understand how play enhances the toddler’s development. The nurse should encourage parents to play with their toddler and provide opportunities for the toddler to play with other children. The nurse teaches parents about child-proofing and checking the house on a daily basis. Toys must be strong, safe, and too large to swallow or place in the ear or nose. Toddlers need supervision at all times. A variety of play materials, which need not be expensive, and a safe play environment enhance the toddler’s development (Box 7-1).