Health Information Management

Learning Objectives

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary.

2. Describe several ways health information is used.

3. Explain the nine characteristics of quality health data.

4. Explain the four concerns of quality assurance.

5. Explain the functions of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

6. Give some types of statistics kept by the NCHS.

7. Define total quality management.

9. Discuss the importance of healthcare standards in medical facilities.

Vocabulary

adverse event An injury caused by medical management rather than the underlying condition of the patient.

circumvent (suhr-kuhm-vent′) To manage to get around, especially by ingenuity or strategy.

contraindications (kahn-truh-in-duh-ka′-shuns) Factors, such as symptoms or conditions, that make a particular treatment or procedure inadvisable.

disparities (di-spar′-uh-tez) Fundamentally different and often incongruous elements; elements that are markedly distinct in quality or character.

encrypted (in-kript′-ed) Encoded; converted from one system of communication to another.

erroneous (eh-ro′-ne-uhs) Containing or characterized by error or assumption.

near miss A situation in which an error is caught or corrected before it affects the patient.

nosocomial (no-suh-ko′-me-uhl) Originating or taking place in a hospital.

potentially compensable event (PCE) An adverse occurrence, usually involving a patient, that could result in a financial obligation for a business or organization.

quality assurance (QA) Activities designed to increase the quality of a product or service through process or system changes that increase efficiency or effectiveness.

sentinel events Unexpected occurrences involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof.

transposed Altered in sequence; interchanged.

Scenario

Laura Kelly graduated from her medical assistant training 1 year ago and is now employed at a freestanding urgent care center. She works with the quality assurance staff and also performs front office duties. She enjoys working with statistics, is very detail oriented, has excellent computer and coding skills, and is able to comprehend lengthy regulatory text, such as that used in the rules and guidelines established by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). She has proven to be a valuable employee, and her efforts help the center comply with privacy laws.

Laura thought that quality assurance involved only patient satisfaction when she began working for the center. She has learned that this is just a small part of the total quality picture of the facility. The center has developed a patient questionnaire to solicit input from patients, and she enjoys talking with them about their experiences. Laura rarely encounters complaints, and she is proud to work for a medical facility that employs individuals who are concerned about giving exceptional care to patients. She understands that providing quality in a healthcare facility has many aspects.

Laura also realizes that health information encompasses much more than the patient’s medical record. She knows that health statistics are vital to research and that physicians rely on statistical information when prescribing drugs, giving treatments, planning for future growth, deciding on which services to offer, and performing other services. Providers frequently contact Laura to determine how many procedures of a certain type were done at the center during a given period. The facility’s database is very sophisticated and allows her to access many types of statistics quickly. Her office also monitors people who enter the database and what information is accessed. Monitoring access is one method of ensuring that privacy is maintained.

Laura has attended continuing education workshops, which provided up-to-date information and enabled her to help the staff stay in compliance with the numerous regulations that govern the facility. She is eager to learn and assist her employers in keeping the center safe for all patients and visitors.

While studying this chapter, think about the following questions:

Before the 1990s, practitioners in the healthcare field were barely familiar with the term “health information management.” Today, this well-respected profession employs thousands of individuals across the United States. As more medical facilities move toward computer-based medical records, more trained health information management professionals are needed. The medical assistant may want to pursue employment in this growing field.

The health information management profession is supported by a national organization, the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA). In 1994 the association’s House of Delegates developed the following statement:

Health information management is the profession that focuses on healthcare data and the management of healthcare information resources. The profession addresses the nature, structure, and translation of data into usable forms of information for the advancement of health and healthcare of individuals and populations. Health information professionals collect, integrate, and analyze primary and secondary healthcare data; disseminate information; and manage information resources related to research, planning, provision, and evaluation of healthcare services.

Evolution of the Profession

In 1928 the American College of Surgeons realized that accurate medical records promoted good medical care. This desire for quality led to the establishment of the Association of Record Librarians of North America. In 1970 the organization changed its name to the American Medical Record Association. Medical records professionals found employment in hospitals, health clinics, insurance companies, and other organizations that used medical records. In 1991 the organization became known as the American Health Information Management Association. Advances in technology have brought the health information management profession from a paper-based environment into a highly sophisticated computer age, where physicians can access patient and statistical data in seconds.

Health Information Certifications

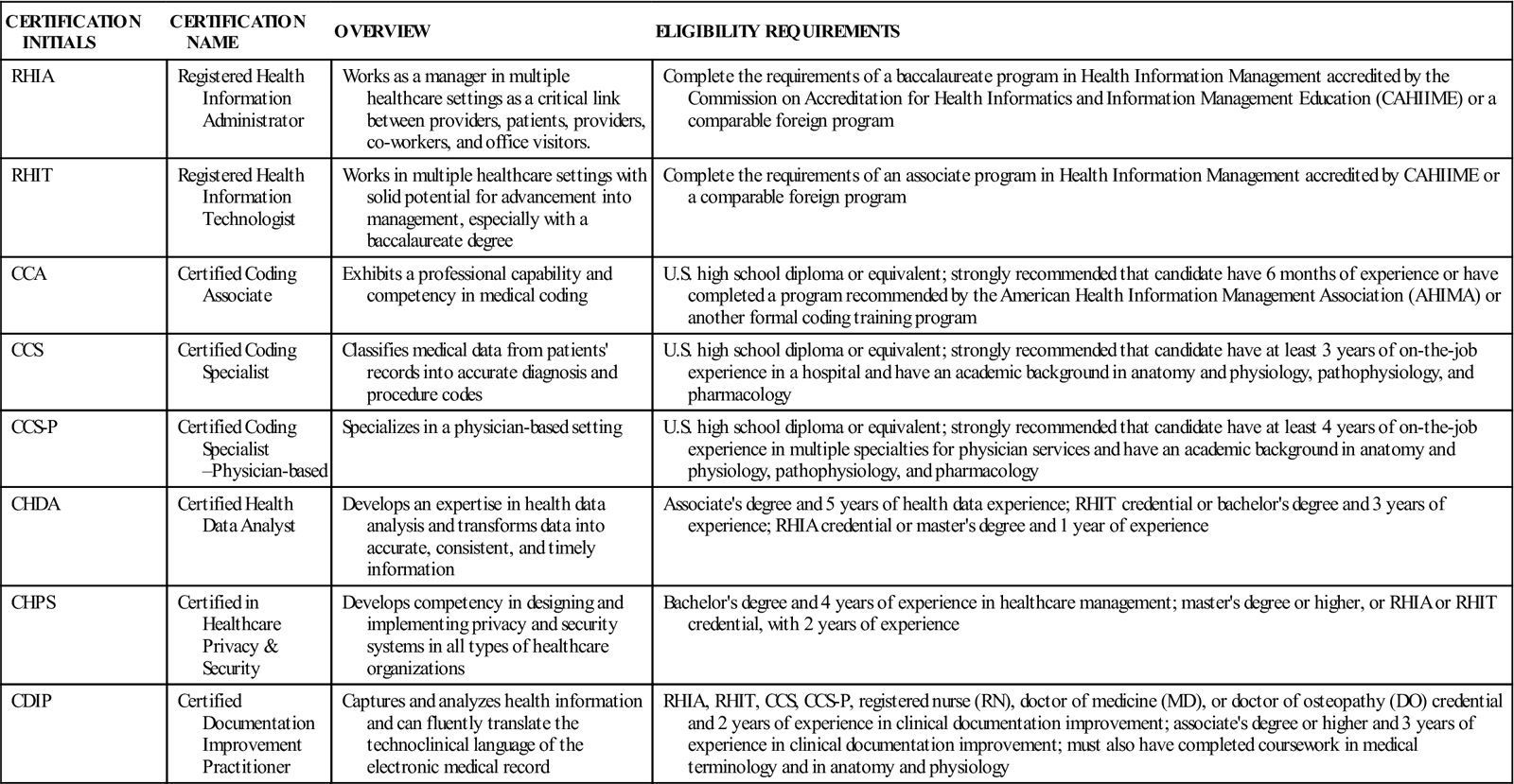

AHIMA offers certifications in health information management, coding, and healthcare privacy and security. Because healthcare facilities are now provided financial incentives for converting to electronic medical records, the need for individuals in health information careers grows each year. Medical facilities need employees who can manipulate data and, at the same time, can keep patient records accurate and confidential. Health Information Technology certifications include:

• Registered Health Information Administrator (RHIA)

• Registered Health Information Technician (RHIT)

• Certified Coding Associate (CCA)

• Certified Coding Specialist (CCS)

• Certified Coding Specialist—Physician-based (CCS-P)

• Certified Health Data Analyst (CHDA)

• Certified in Healthcare Privacy & Security (CHPS)

Additional information about each certification and the eligibility requirements can be found in Table 16-1 and on the Evolve site at evolve.elsevier.com/kinn.

TABLE 16-1

Certifications in Healthcare Technology

| CERTIFICATION INITIALS | CERTIFICATION NAME | OVERVIEW | ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS |

| RHIA | Registered Health Information Administrator | Works as a manager in multiple healthcare settings as a critical link between providers, patients, providers, co-workers, and office visitors. | Complete the requirements of a baccalaureate program in Health Information Management accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Health Informatics and Information Management Education (CAHIIME) or a comparable foreign program |

| RHIT | Registered Health Information Technologist | Works in multiple healthcare settings with solid potential for advancement into management, especially with a baccalaureate degree | Complete the requirements of an associate program in Health Information Management accredited by CAHIIME or a comparable foreign program |

| CCA | Certified Coding Associate | Exhibits a professional capability and competency in medical coding | U.S. high school diploma or equivalent; strongly recommended that candidate have 6 months of experience or have completed a program recommended by the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) or another formal coding training program |

| CCS | Certified Coding Specialist | Classifies medical data from patients’ records into accurate diagnosis and procedure codes | U.S. high school diploma or equivalent; strongly recommended that candidate have at least 3 years of on-the-job experience in a hospital and have an academic background in anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology |

| CCS-P | Certified Coding Specialist–Physician-based | Specializes in a physician-based setting | U.S. high school diploma or equivalent; strongly recommended that candidate have at least 4 years of on-the-job experience in multiple specialties for physician services and have an academic background in anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology |

| CHDA | Certified Health Data Analyst | Develops an expertise in health data analysis and transforms data into accurate, consistent, and timely information | Associate’s degree and 5 years of health data experience; RHIT credential or bachelor’s degree and 3 years of experience; RHIA credential or master’s degree and 1 year of experience |

| CHPS | Certified in Healthcare Privacy & Security | Develops competency in designing and implementing privacy and security systems in all types of healthcare organizations | Bachelor’s degree and 4 years of experience in healthcare management; master’s degree or higher, or RHIA or RHIT credential, with 2 years of experience |

| CDIP | Certified Documentation Improvement Practitioner | Captures and analyzes health information and can fluently translate the technoclinical language of the electronic medical record | RHIA, RHIT, CCS, CCS-P, registered nurse (RN), doctor of medicine (MD), or doctor of osteopathy (DO) credential and 2 years of experience in clinical documentation improvement; associate’s degree or higher and 3 years of experience in clinical documentation improvement; must also have completed coursework in medical terminology and in anatomy and physiology |

Uses of Healthcare Data

Healthcare data are used primarily to plan patient care, to plan for the future growth and development of the facility, and to ensure that patients receive continuity of care from one healthcare provider to another. However, the information provided by healthcare records can be useful in other ways.

Primary data are the information in the actual medical record; secondary data are generated from the information in the medical record. For example, when a drug is evaluated, statistics must be kept to help the manufacturers determine its effectiveness. Information on side effects and other contraindications is reviewed and used to make the drug safer and more marketable.

Healthcare organizations gather information on the number of patients who enter the facility with the same diagnosis. This and other information helps them plan the types of equipment required to meet the needs of this patient group. For instance, if the facility is located in a geographic area with a large number of patients with cardiac disease, the hospital may need to add a cardiac intensive care unit. Healthcare data and statistics guide planning for the needs of next week and the next decade.

The Federal Register (FR), which is published by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), provides daily access to rules, proposed rules, and notices of federal agencies and organizations, including those dealing with healthcare. Today’s technology allows NARA to e-mail the FR’s table of contents each day (Monday through Friday). Also, healthcare information can be accessed on the agency’s Web site, which offers updated information about rules and regulations currently in effect, changes, new proposals, and final rulings. The FR is an excellent source of health data, and every medical facility should receive at least the daily table of contents e-mail, which can help the medical facility stay up-to-date on new regulations and changes in current ones.

Third-party payers use healthcare information to determine whether claims should be paid. The data provide proof that a certain procedure or treatment was medically necessary and therefore its cost should be reimbursed. Government and regulatory agencies use data to ensure that healthcare facilities are in compliance with the various statutes and standards that govern them. Facilities use data to help determine whether they are providing high-quality healthcare to their patients.

What are High-Quality Data?

The information in a database is only as reliable as the person who enters it into the computer. Nine characteristics of quality healthcare data have been identified: validity, reliability, completeness, recognizability, timeliness, relevance, accessibility, security, and legality.

• Recognizability. All users of health information must be able to interpret the data in the health record. The facility should insist on consistent use of abbreviations to prevent misunderstandings when a patient’s chart is reviewed. Some systems display charts to show an increase or a decline in basic vital signs (e.g., blood pressure, weight, and temperature). Such a system allows the physician to track symptoms over time without having to search through a paper record (Figure 16-1).

• Legality. Medical records are regulated by many statutes. The laws on retention of records vary from state to state. Medical records cannot be altered, and they should be corrected according to accepted guidelines. The record must be completely legible and must be authenticated properly (Figure 16-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree