Health Assessment and Physical Examination

Objectives

• Discuss the purposes of physical assessment.

• Describe interview techniques used to enhance communication during history taking.

• Make environmental preparations before an examination.

• Identify data to collect from the nursing history before an examination.

• Demonstrate the techniques used with each physical assessment skill.

• Discuss normal physical findings in a young, middle-age, and older adult.

• Discuss ways to incorporate health promotion and health teaching into the examination.

• Identify ways to use physical assessment skills during routine nursing care.

• Describe physical measurements made in assessing each body system.

• Identify self-screening examinations commonly performed by patients.

• Identify preventive screenings and the appropriate age(s) for each screening to occur.

Key Terms

Adventitious sounds, p. 525

Alopecia, p. 504

Aphasia, p. 557

Apical impulse or point of maximal impulse (PMI), p. 527

Arcus senilis, p. 511

Atrophied, p. 554

Auscultation, p. 494

Borborygmi, p. 544

Bruit, p. 532

Cerumen, p. 513

Clubbing, p. 536

Conjunctivitis, p. 511

Cyanosis, p. 500

Distention, p. 543

Dysrhythmia, p. 530

Ectropion, p. 510

Entropion, p. 510

Edema, p. 502

Erythema, p. 501

Excoriation, p. 516

Goniometer, p. 553

Hypertonicity, p. 554

Hypotonicity, p. 554

Indurated, p. 502

Inspection, p. 493

Integumentary system, p. 498

Jaundice, p. 501

Kyphosis, p. 551

Lordosis, p. 552

Malignancy, p. 519

Murmurs, p. 530

Nystagmus, p. 509

Olfaction, p. 493

Orthopnea, p. 524

Osteoporosis, p. 552

Ototoxicity, p. 514

Palpation, p. 493

Percussion, p. 494

Peristalsis, p. 544

PERRLA, p. 511

Petechiae, p. 502

Pigmentation, p. 500

Polyps, p. 516

Ptosis, p. 510

Scoliosis, p. 552

Stenosis, p. 531

Striae, p. 543

Syncope, p. 531

Thrill, p. 530

Turgor, p. 502

Ventricular gallop, p. 530

Vocal or tactile fremitus, p. 524

![]()

The health assessment and physical examination are the first steps toward providing safe and competent nursing care. The nurse is in a unique position to determine each patient’s current health status, distinguish variations from the norm, and recognize improvements or deterioration in his or her condition. As a nurse, you must be able to recognize and interpret each patient’s behavioral and physical presentation. By performing health assessments and physical examinations, you will identify health patterns and evaluate each patient’s response to treatments and therapies.

Nurses gather assessment data about patients’ past and current health conditions in a variety of ways, using a comprehensive or focused approach, depending on the patient situation. Assessments are performed at health fairs, at screening clinics, in a health provider’s office, in acute care agencies, or in patients’ homes. Depending on the outcome of an assessment, a nurse considers evidence-based recommendations for care based on a patient’s values, the health provider’s clinical expertise, or own personal experience.

A complete health assessment involves a nursing history (see Chapter 16) and behavioral and physical examination. Through the health history interview you gather subjective data about a patient’s condition. You obtain objective data while observing a patient’s behavior and overall presentation. You identify additional objective data through a head-to-toe body system review during the physical examination. Your clinical judgments are based on all of the gathered data to create a plan of care for each situation. With accurate data you create a patient-centered care plan, identifying the nursing diagnoses, desired patient outcomes, and nursing interventions. Continuity in health care improves when you evaluate a patient by making ongoing, objective, and comprehensive assessments.

Purposes of the Physical Examination

A physical examination is conducted as an initial evaluation in triage for emergency care; for routine screening to promote wellness behaviors and preventive health care measures; to determine eligibility for health insurance, military service, or a new job; or to admit a patient to a hospital or long-term care facility. After considering the patient’s current condition, a nurse selects a focused physical examination on a specific system or area. For example, when a patient is having a severe asthma episode, the nurse first focuses on the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems so treatments can begin immediately. When the patient is no longer at risk for a bad outcome or injury, the nurse performs a more comprehensive examination of other body systems.

For patients who are hospitalized, a nurse integrates the collection of physical assessment data during routine patient care, validating findings with what is known about the patient’s health history. For example, on entering a patient’s room a nurse may notice behavioral patient cues that indicate comfort, anxiety, or sadness; assess the skin during the bed bath; or assess physical movements and swallowing abilities while administering medications. Use physical examination to do the following:

• Gather baseline data about the patient’s health status.

• Support or refute subjective data obtained in the nursing history.

• Identify and confirm nursing diagnoses.

• Make clinical decisions about a patient’s changing health status and management.

Cultural Sensitivity

Respect the cultural differences among patients from a variety of backgrounds when completing an examination. It is important to remember that cultural differences influence patient behaviors. Consider the patient’s health beliefs, use of alternative therapies, nutrition habits, relationships with family, and comfort with physical closeness during the examination and history. These factors will affect your approach as well as the type of findings you might expect.

Be culturally aware and avoid stereotyping on the basis of gender or race. There is a difference between cultural characteristics and physical characteristics. Learn to recognize common characteristics and disorders among members of ethnic populations within the community. It is equally important to recognize variations in physical characteristics such as in the skin and musculoskeletal system, which are related to racial variables. By recognizing cultural diversity, you show respect for each patient’s uniqueness, leading to higher-quality care and improved clinical outcomes (see Chapter 9).

Preparation for Examination

Physical examination is a routine part of a nurse’s patient assessment. In many care settings a head-to-toe physical assessment is required daily. You perform a reassessment when a patient’s condition changes as it improves or worsens. In some health care settings such as during a home health visit a focused physical examination is preferred. Proper preparation of the environment, equipment, and patient ensures a smooth physical examination with few interruptions. A disorganized approach causes errors and incomplete findings. Safety for confused patients should be a priority; never leave a confused or combative patient alone during an examination.

Infection Control

Some patients present with open skin lesions, infected wounds, or other communicable diseases. Use standard precautions throughout an examination (see Chapter 28). When an open sore or microorganism is present, wear gloves to reduce contact with contaminants. If a patient has excessive drainage or there is a risk of splattering from a wound, additional personal protective equipment such as an isolation gown or eye shield should be used. Follow agency hand hygiene policies before initiating and after completing a physical assessment.

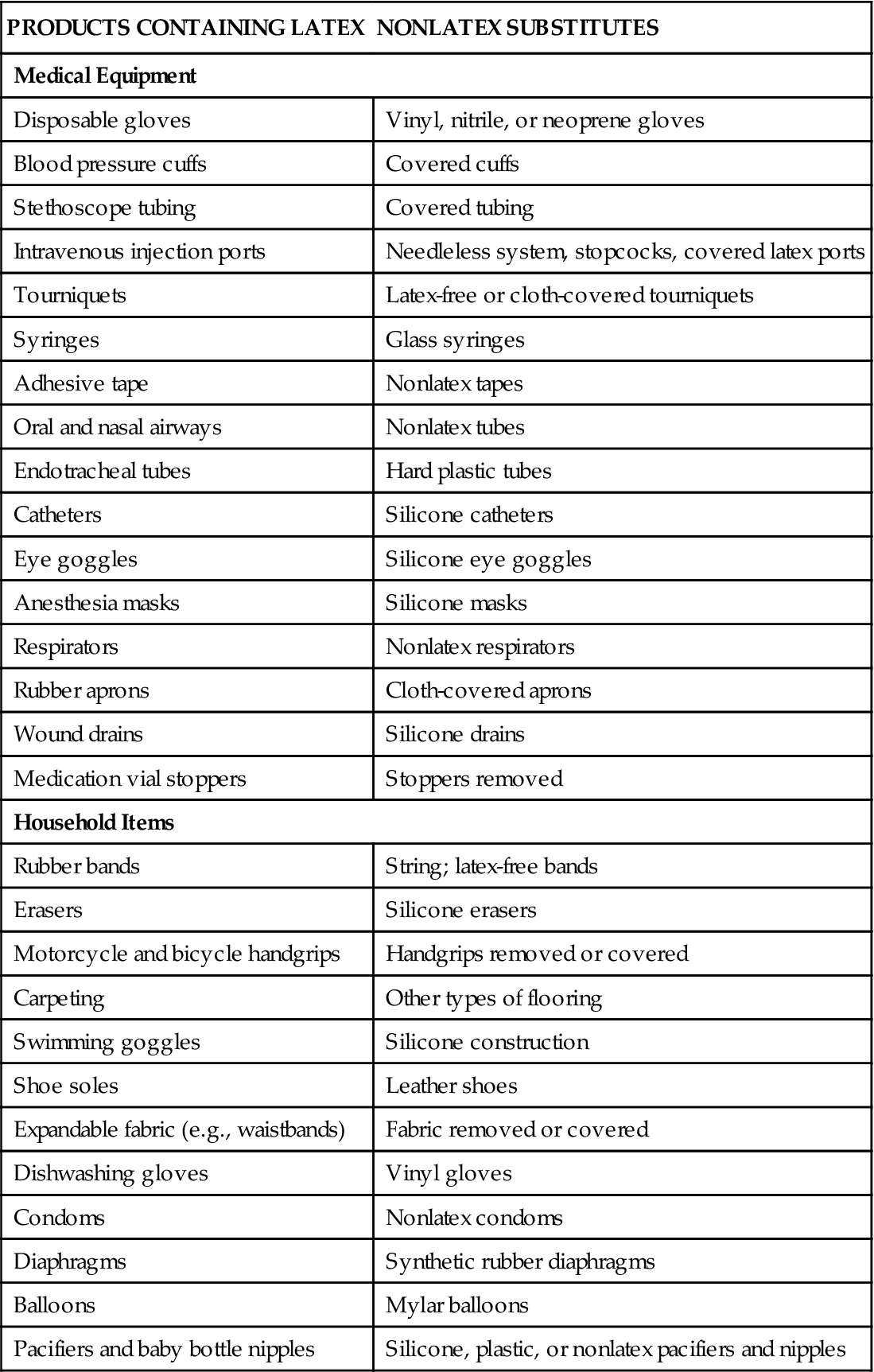

Although most health care agencies make nonlatex gloves available, it is your responsibility to identify latex allergies in patients and use equipment items that are latex free. By recognizing risk factors for latex allergies, the patient remains free of a natural rubber latex (NRL) allergy response. Two types of allergic responses appear with NRL. The most immediate is an immunological reaction type 1 response, for which the body develops antibodies known as immunoglobulin E that can lead to an anaphylactic response. Atopy occurs when there is an increased tendency for the body to form antibodies as a result of the immune response. The second is the allergic contact dermatitis type 4 response, which causes a delayed reaction that appears 12 to 48 hours after exposure (Bundesen, 2008). Both require prior exposure to the substance to which the body reacts. The severity of the response varies among individuals. Table 30-1 provides a short list of products that contain latex and suggests available alternatives.

TABLE 30-1

Products Containing Latex and Nonlatex Substitutes*

| PRODUCTS CONTAINING LATEX | NONLATEX SUBSTITUTES |

| Medical Equipment | |

| Disposable gloves | Vinyl, nitrile, or neoprene gloves |

| Blood pressure cuffs | Covered cuffs |

| Stethoscope tubing | Covered tubing |

| Intravenous injection ports | Needleless system, stopcocks, covered latex ports |

| Tourniquets | Latex-free or cloth-covered tourniquets |

| Syringes | Glass syringes |

| Adhesive tape | Nonlatex tapes |

| Oral and nasal airways | Nonlatex tubes |

| Endotracheal tubes | Hard plastic tubes |

| Catheters | Silicone catheters |

| Eye goggles | Silicone eye goggles |

| Anesthesia masks | Silicone masks |

| Respirators | Nonlatex respirators |

| Rubber aprons | Cloth-covered aprons |

| Wound drains | Silicone drains |

| Medication vial stoppers | Stoppers removed |

| Household Items | |

| Rubber bands | String; latex-free bands |

| Erasers | Silicone erasers |

| Motorcycle and bicycle handgrips | Handgrips removed or covered |

| Carpeting | Other types of flooring |

| Swimming goggles | Silicone construction |

| Shoe soles | Leather shoes |

| Expandable fabric (e.g., waistbands) | Fabric removed or covered |

| Dishwashing gloves | Vinyl gloves |

| Condoms | Nonlatex condoms |

| Diaphragms | Synthetic rubber diaphragms |

| Balloons | Mylar balloons |

| Pacifiers and baby bottle nipples | Silicone, plastic, or nonlatex pacifiers and nipples |

*This list is intended to provide examples of products and alternatives. It is not complete.

Modified from American Latex Allergy Association: Literature review on latex-food cross-reactivity, 1991-2006, 2011, http://www.latexallergyresources.org/topics/CrossReactiveAllergens.cfm. Accessed September 8, 2011; and Seidel HM et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 7, St Louis, 2011, Mosby;

Environment

A respectful, considerate physical examination requires privacy. In the acute setting, nurses perform assessments in a patient’s room. Examination rooms are used in clinics or office settings. In the home the examination is performed in a space where privacy can be established such as the patient’s bedroom.

Examination spaces need to be well equipped for any procedures. Adequate lighting is necessary to properly illuminate body parts. The hospital patient room can be secured for privacy so patients are comfortable discussing their condition. Eliminate extra noise and take precautions to prevent interruptions from others. The room must be warm enough to maintain comfort.

Depending on the body part being assessed, it may be difficult to perform a selected assessment skill when a patient is in bed or on a stretcher. Special examination tables make positioning easier and body areas more easily accessible. By assisting patients on and off the examination table, injury can be avoided, and falls prevented. Examination tables can be uncomfortable; elevate the head of the table about 30 degrees. A small pillow helps with head and neck comfort. If the examination is completed in the patient room, raise the patient’s bed to be able to reach him or her more easily.

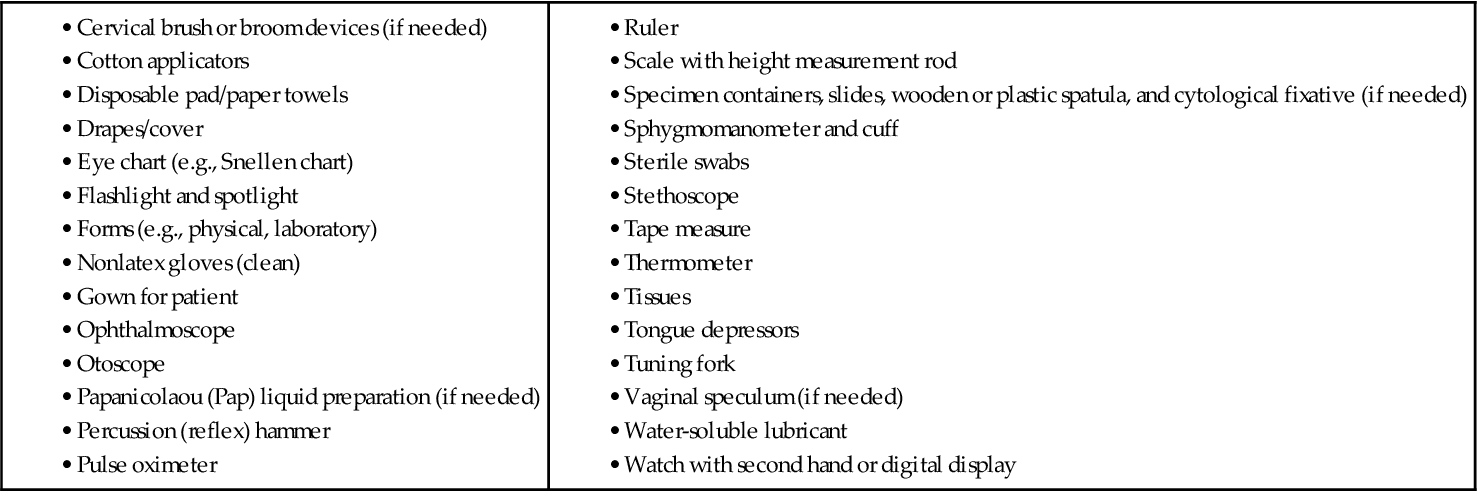

Equipment

Perform hand hygiene thoroughly before handling equipment and starting an examination. Arrange any necessary equipment so that it is readily available and easy to use. Prepare equipment as appropriate (e.g., warm the diaphragm of the stethoscope between the hands before applying it to the skin). Be sure that equipment functions properly before using it (e.g., ensure that the ophthalmoscope and otoscope have good batteries and light bulbs). Box 30-1 lists typical equipment used during a physical examination.

Physical Preparation of the Patient

To show respect for a patient, ensure that physical comfort needs are met. Before starting, ask if the patient needs to use the restroom. An empty bladder and bowel facilitate examination of the abdomen, genitalia, and rectum. Collection of urine or fecal specimens occurs at this time if needed.

Physical preparation involves making certain that patient privacy is maintained with proper dress and draping. The patient in the hospital likely is wearing only a simple gown. In the clinic or health care provider’s office the patient needs to undress and usually is provided a disposable paper cover or paper gown. If the examination is limited to certain body systems, it is not always necessary for the patient to undress completely. Provide the patient privacy and plenty of time to undress to avoid embarrassment. After changing into the recommended gown or cover, the patient sits or lies down on the examination table with a light drape over the lap or lower trunk. Make sure that he or she stays warm by eliminating drafts, controlling room temperature, and providing warm blankets. Routinely ask if he or she is comfortable.

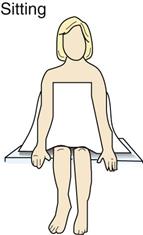

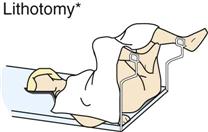

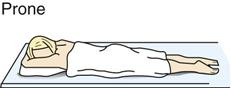

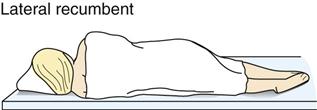

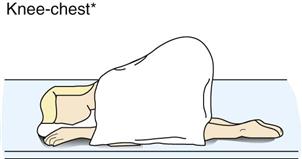

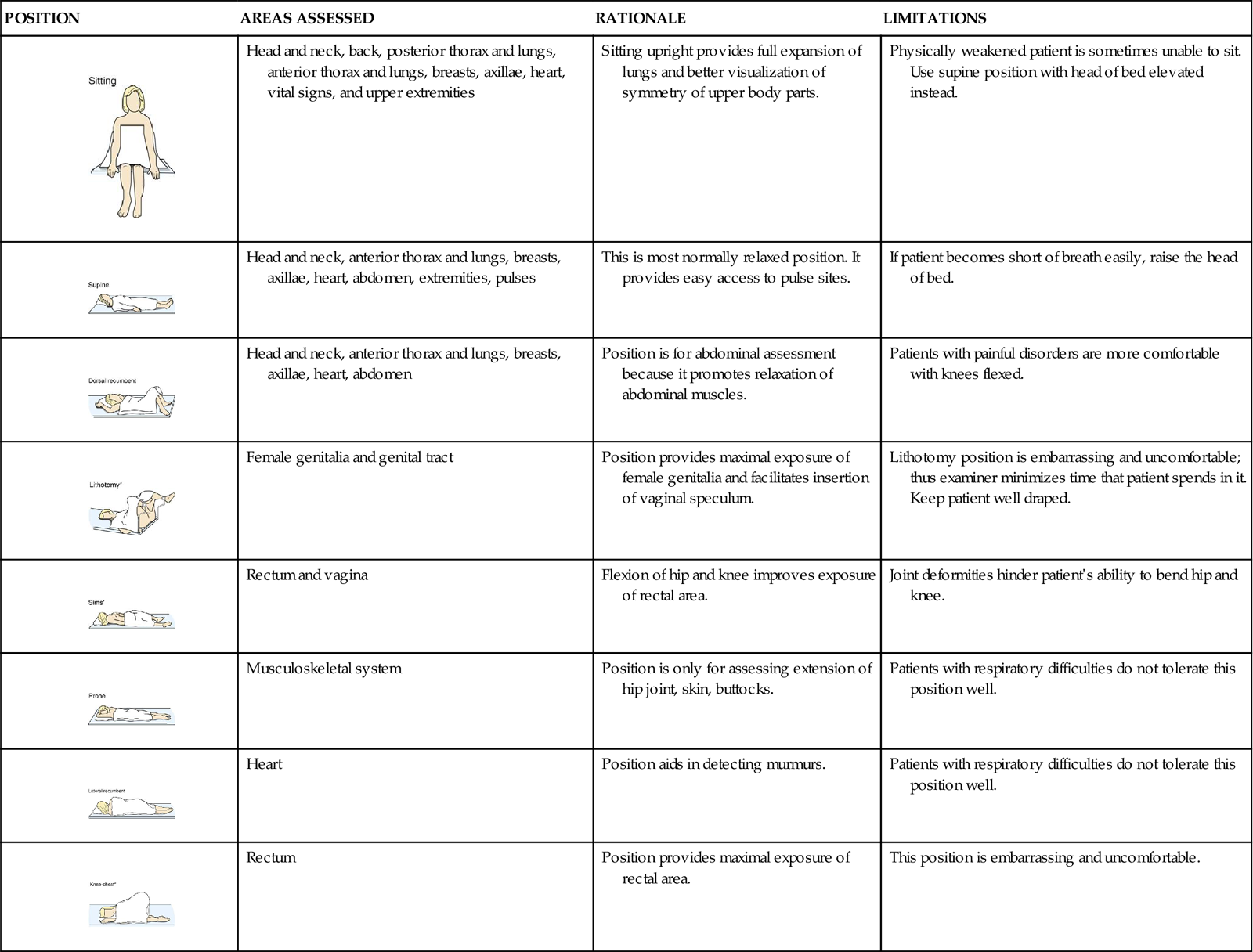

Positioning.

During the examination ask the patient to assume proper positions so body parts are accessible and he or she stays comfortable. Table 30-2 lists the preferred positions for each part of the examination and contains figures illustrating the positions. Patients’ abilities to assume positions depend on their physical strength, mobility, ease of breathing, age, and degree of wellness. After explaining the positions, help the patient to assume them. Take care to maintain respect and show consideration by adjusting the drapes so that only the area examined is accessible. During the examination a patient may need to assume more than one position. To decrease the number of position changes, organize the examination so all techniques requiring a sitting position are completed first, followed by those that require a supine position next, and so forth. Use extra care when positioning older adults with disabilities and limitations.

TABLE 30-2

| POSITION | AREAS ASSESSED | RATIONALE | LIMITATIONS |

| Head and neck, back, posterior thorax and lungs, anterior thorax and lungs, breasts, axillae, heart, vital signs, and upper extremities | Sitting upright provides full expansion of lungs and better visualization of symmetry of upper body parts. | Physically weakened patient is sometimes unable to sit. Use supine position with head of bed elevated instead. |

| Head and neck, anterior thorax and lungs, breasts, axillae, heart, abdomen, extremities, pulses | This is most normally relaxed position. It provides easy access to pulse sites. | If patient becomes short of breath easily, raise the head of bed. |

| Head and neck, anterior thorax and lungs, breasts, axillae, heart, abdomen | Position is for abdominal assessment because it promotes relaxation of abdominal muscles. | Patients with painful disorders are more comfortable with knees flexed. |

| Female genitalia and genital tract | Position provides maximal exposure of female genitalia and facilitates insertion of vaginal speculum. | Lithotomy position is embarrassing and uncomfortable; thus examiner minimizes time that patient spends in it. Keep patient well draped. |

| Rectum and vagina | Flexion of hip and knee improves exposure of rectal area. | Joint deformities hinder patient’s ability to bend hip and knee. |

| Musculoskeletal system | Position is only for assessing extension of hip joint, skin, buttocks. | Patients with respiratory difficulties do not tolerate this position well. |

| Heart | Position aids in detecting murmurs. | Patients with respiratory difficulties do not tolerate this position well. |

| Rectum | Position provides maximal exposure of rectal area. | This position is embarrassing and uncomfortable. |

*Some patients with arthritis or other joint deformities are unable to assume this position.

Psychological Preparation of a Patient

Many patients find an examination stressful or tiring, or they experience anxiety about possible findings. A thorough explanation of the purpose and steps of each assessment lets a patient know what to expect and how to cooperate. Adapt explanations to the patient’s level of understanding and encourage him or her to ask questions and comment on any discomfort. Convey an open, professional approach while remaining relaxed. A quiet, formal demeanor inhibits the patient’s ability to communicate, but a style that is too casual may cause him or her to doubt an examiner’s competence (Seidel et al., 2011).

Consider cultural or social norms when performing an examination on a person of the opposite gender. When this situation occurs, another person of the patient’s gender or a culturally approved family member needs to be in the room. By taking this step you demonstrate cultural awareness for a patient’s individual needs. As a side benefit, the second person acts as a witness to the conduct of the examiner and the patient should any question arise.

During the examination, watch the patient’s emotional responses by observing whether his or her facial expressions show fear or concern or if body movements indicate anxiety. When you remain calm, the patient is more likely to relax. Especially if the patient is weak or elderly, it is necessary to pace the examination, pausing at intervals to ask how he or she is tolerating the assessment. If the patient feels alright, the examination can proceed. However, do not force the patient to cooperate based on your schedule. Postponing the examination is advantageous because the findings may be more accurate when the patient can cooperate and relax.

Assessment of Age-Groups

It is necessary to use different interview styles and approaches to physical examination for patients of different age-groups. Your approach will vary with each group. When assessing children, show sensitivity and anticipate the child’s perception of the examination as a strange and unfamiliar experience. Routine pediatric examinations focus on health promotion and illness prevention, particularly for the care of well children who receive competent parenting and have no serious health problems (Josephson and AACAP Work Group, 2007). This examination focuses on growth and development, sensory screening, dental examination, and behavioral assessment. Children who are chronically ill or disabled and foster, foreign-born, or adopted children sometimes require additional examination visits. When examining children, the following tips help in data collection:

• Gather all or part of the history on infants and children from parents or guardians.

• Perform the examination in a nonthreatening area; provide time for play to become acquainted.

• Treat adolescents as adults and individuals because they tend to respond best when treated as such.

A comprehensive health assessment and examination of older adults includes physical data, developmental stage, family relationships, religious and occupational pursuits, and a review of the patient’s cognitive, affective, and social level (Kresevic, 2008). An important aspect is to assess the patient’s ability to perform basic activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, grooming) and complex instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., making phone call).

Throughout the examination recognize that with advancing age the body does not demonstrate obvious injury or disease as vigorously as younger patients and older adults do not always exhibit the expected signs and symptoms (Meiner, 2011). Characteristically older adults present with subtle or atypical signs and symptoms. Principles to follow during examination of an older adult include the following:

Organization of the Examination

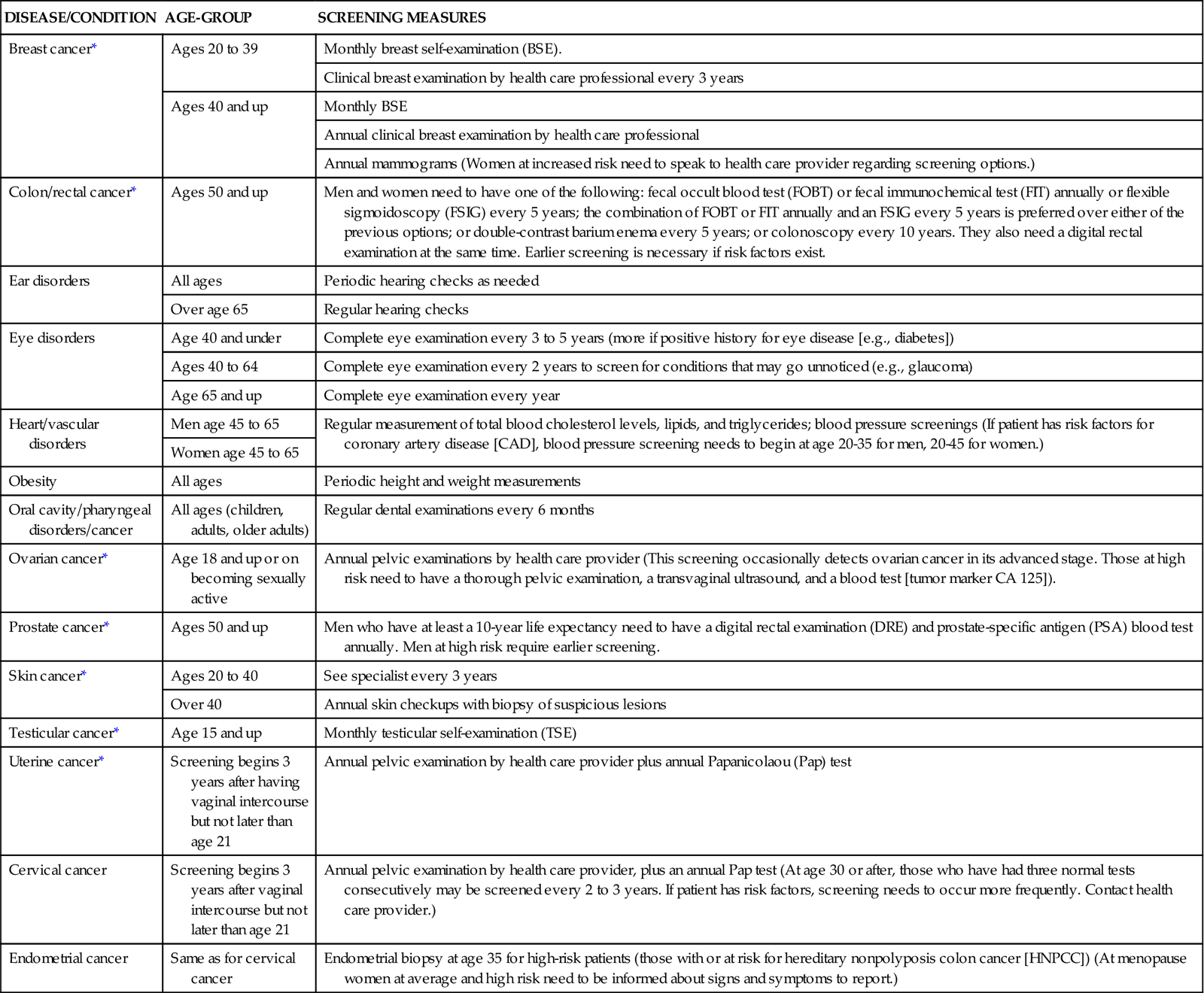

You will conduct a physical examination by assessing each body system. Use judgment to ensure that an examination is relevant and includes the correct assessments. Patients with focused symptoms or needs require only parts of an examination; thus, when a patient comes to a clinic with symptoms of a severe chest cold, a neurological assessment should not be required. A patient entering the emergency department with acute abdominal symptoms requires assessment of the body systems most at risk for being abnormal. However, when a patient is admitted to the hospital, you will perform a complete examination at the time of admission and at least once each day. Agency guidelines may define the components of a complete examination (see agency policy). A patient in the community seeks screening for specific conditions, often dependent on the patient’s age or health risks listed in Table 30-3.

TABLE 30-3

Recommended Preventive Screenings

| DISEASE/CONDITION | AGE-GROUP | SCREENING MEASURES |

| Breast cancer* | Ages 20 to 39 | Monthly breast self-examination (BSE). |

| Clinical breast examination by health care professional every 3 years | ||

| Ages 40 and up | Monthly BSE | |

| Annual clinical breast examination by health care professional | ||

| Annual mammograms (Women at increased risk need to speak to health care provider regarding screening options.) | ||

| Colon/rectal cancer* | Ages 50 and up | Men and women need to have one of the following: fecal occult blood test (FOBT) or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) annually or flexible sigmoidoscopy (FSIG) every 5 years; the combination of FOBT or FIT annually and an FSIG every 5 years is preferred over either of the previous options; or double-contrast barium enema every 5 years; or colonoscopy every 10 years. They also need a digital rectal examination at the same time. Earlier screening is necessary if risk factors exist. |

| Ear disorders | All ages | Periodic hearing checks as needed |

| Over age 65 | Regular hearing checks | |

| Eye disorders | Age 40 and under | Complete eye examination every 3 to 5 years (more if positive history for eye disease [e.g., diabetes]) |

| Ages 40 to 64 | Complete eye examination every 2 years to screen for conditions that may go unnoticed (e.g., glaucoma) | |

| Age 65 and up | Complete eye examination every year | |

| Heart/vascular disorders | Men age 45 to 65 | Regular measurement of total blood cholesterol levels, lipids, and triglycerides; blood pressure screenings (If patient has risk factors for coronary artery disease [CAD], blood pressure screening needs to begin at age 20-35 for men, 20-45 for women.) |

| Women age 45 to 65 | ||

| Obesity | All ages | Periodic height and weight measurements |

| Oral cavity/pharyngeal disorders/cancer | All ages (children, adults, older adults) | Regular dental examinations every 6 months |

| Ovarian cancer* | Age 18 and up or on becoming sexually active | Annual pelvic examinations by health care provider (This screening occasionally detects ovarian cancer in its advanced stage. Those at high risk need to have a thorough pelvic examination, a transvaginal ultrasound, and a blood test [tumor marker CA 125]). |

| Prostate cancer* | Ages 50 and up | Men who have at least a 10-year life expectancy need to have a digital rectal examination (DRE) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test annually. Men at high risk require earlier screening. |

| Skin cancer* | Ages 20 to 40 | See specialist every 3 years |

| Over 40 | Annual skin checkups with biopsy of suspicious lesions | |

| Testicular cancer* | Age 15 and up | Monthly testicular self-examination (TSE) |

| Uterine cancer* | Screening begins 3 years after having vaginal intercourse but not later than age 21 | Annual pelvic examination by health care provider plus annual Papanicolaou (Pap) test |

| Cervical cancer | Screening begins 3 years after vaginal intercourse but not later than age 21 | Annual pelvic examination by health care provider, plus an annual Pap test (At age 30 or after, those who have had three normal tests consecutively may be screened every 2 to 3 years. If patient has risk factors, screening needs to occur more frequently. Contact health care provider.) |

| Endometrial cancer | Same as for cervical cancer | Endometrial biopsy at age 35 for high-risk patients (those with or at risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer [HNPCC]) (At menopause women at average and high risk need to be informed about signs and symptoms to report.) |

*Data from American Cancer Society: Cancer facts and figures 2011, Atlanta, 2011, The Society; website for further information on preventative screenings: Guide to clinical preventive services, AHRQ Publication No. 05-0570, Rockville, Md, 2011, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, http://www.ahrp.gov/.

Any physical examination should follow a systematic routine to avoid missing important findings. A head-to-toe approach includes all body systems, and the examiner recalls and performs each step in a predetermined order. For an adult the examination begins with an assessment of the head and neck and progresses methodically down the body to incorporate all body systems. The following tips help keep an examination well organized:

Techniques of Physical Assessment

The four techniques used in a physical examination are inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

Inspection

To inspect, carefully look, listen, and smell to distinguish normal from abnormal findings. To do so, you must be aware of any personal visual, hearing, or olfactory deficits. It is important to deliberately practice this skill and learn to recognize all of the possible pieces of data that can be gathered through inspection alone. Inspection occurs when interacting with a patient, watching for nonverbal expressions of emotional and mental status. Physical movements and structural components can also be identified in such an informal way. Most important, be deliberate and pay attention to detail. Follow these guidelines to achieve the best results during inspection:

• Make sure that adequate lighting is available, either direct or tangential.

• Use a direct lighting source (e.g., a penlight or lamp) to inspect body cavities.

• Inspect each area for size, shape, color, symmetry, position, and abnormality.

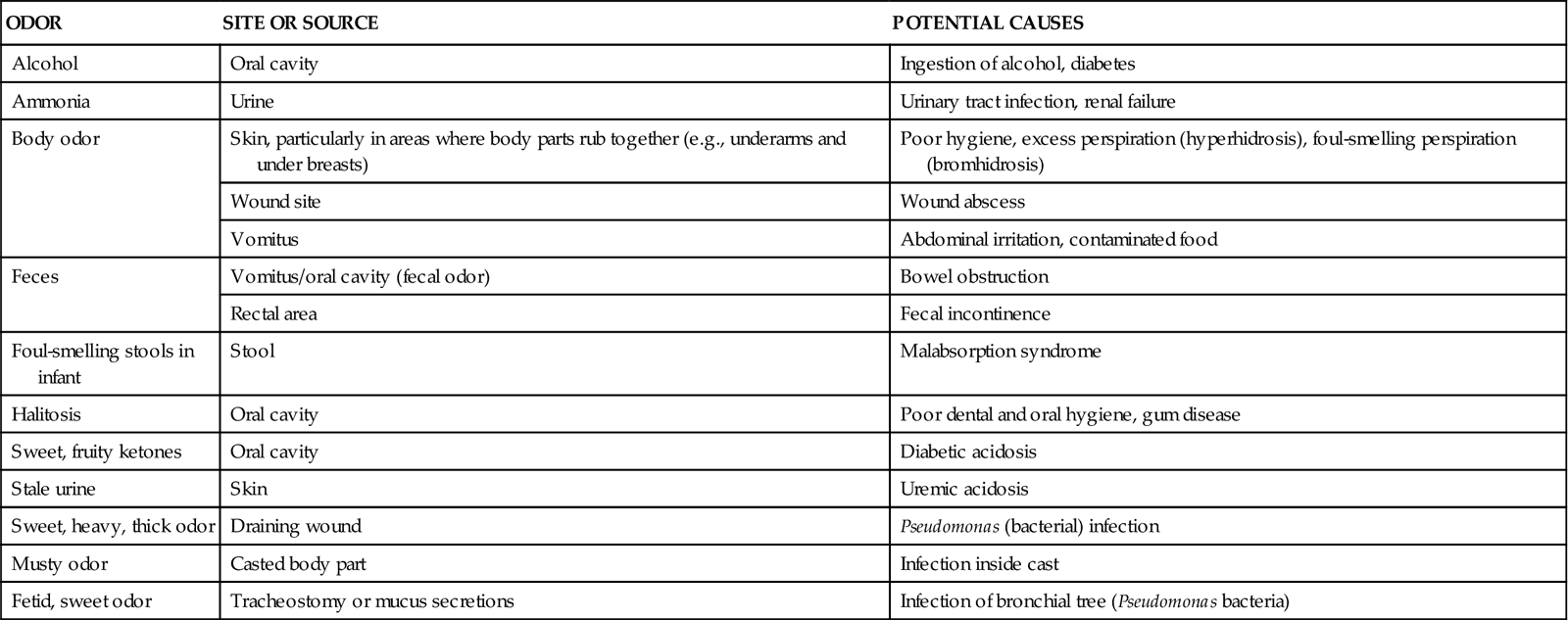

While assessing a patient, recognize the nature and source of body odors (Table 30-4). An unusual odor often indicates an underlying pathology. Olfaction helps to detect abnormalities that cannot be recognized by any other means. For example, when a patient’s breath has a sweet, fruity odor, assess for signs of diabetes. Continue to inspect various parts of the body during the physical examination. Palpation may be used concurrently with inspection, or it may follow in a more deliberate fashion.

TABLE 30-4

Assessment of Characteristic Odors

| ODOR | SITE OR SOURCE | POTENTIAL CAUSES |

| Alcohol | Oral cavity | Ingestion of alcohol, diabetes |

| Ammonia | Urine | Urinary tract infection, renal failure |

| Body odor | Skin, particularly in areas where body parts rub together (e.g., underarms and under breasts) | Poor hygiene, excess perspiration (hyperhidrosis), foul-smelling perspiration (bromhidrosis) |

| Wound site | Wound abscess | |

| Vomitus | Abdominal irritation, contaminated food | |

| Feces | Vomitus/oral cavity (fecal odor) | Bowel obstruction |

| Rectal area | Fecal incontinence | |

| Foul-smelling stools in infant | Stool | Malabsorption syndrome |

| Halitosis | Oral cavity | Poor dental and oral hygiene, gum disease |

| Sweet, fruity ketones | Oral cavity | Diabetic acidosis |

| Stale urine | Skin | Uremic acidosis |

| Sweet, heavy, thick odor | Draining wound | Pseudomonas (bacterial) infection |

| Musty odor | Casted body part | Infection inside cast |

| Fetid, sweet odor | Tracheostomy or mucus secretions | Infection of bronchial tree (Pseudomonas bacteria) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree