Global Nurse Migration

Barbara L. Nichols, Catherine R. Davis and Donna R. Richardson

“Migration is one of the defining issues of the 21st century. It is now an essential, inevitable and potentially beneficial component of the economic and social life of every country and region.”

—Brunson McKinley, Director General, International Organization for Migration

Migration within and between countries is commonplace and is expected to grow. The shortage of health care workers in developed countries drives migration, fuels aggressive recruitment, and is being temporarily resolved with migrant workers from developing countries. Since the domestic source of nurses in many countries is not keeping up with the increased demand, the gap will continue to be filled by foreign-educated nurses. This chapter discusses key nurse migration trends and challenges and their policy implications.

Migration and the Global Health Care Workforce

General Trends in Migration

Migration is the movement of people from one country to another (international or external migration) or from one region of a country to another (internal migration). In general, five main trends characterize migration in the twenty-first century:

1. The number of international migrants is increasing; it is estimated that 1 in 35 individuals, worldwide, is an international migrant (Kingma, 2006).

2. There has been growth in the migration of skilled and qualified workers (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2002), with female migrants accounting for an increasing proportion of all migrants.

3. Women are reported to be migrating without partners or families (Kingma, 2007).

4. Violence against health care workers and gender-based discrimination persist in many countries.

5. Migration affects both developed and developing countries.

Almost all countries are affected by migration in one way or another, but developing countries are disproportionately affected because of their much smaller workforces and greater health care needs. Some countries provide the world with needed goods and services and are considered source countries for migration. Other nations accept the goods and services provided and are considered receiving countries. The United States is predominantly a receiving country and a prime destination for international migration.

As of 2008, immigrants made up 12.5% (38 million) of the total U.S. population. Mexican-born immigrants accounted for 30.1% of all foreign-born individuals living in the U.S., followed by immigrants born in the Philippines (4.4%), India (4.3%), and China (3.6%). These four countries, combined with Vietnam, El Salvador, Korea, Cuba, Canada, and the Dominican Republic, made up 57.7% of all foreign-born individuals living in the U.S. in 2008 (Terrazas & Batalova, 2009). This pattern of Asian and Mexican immigration is quite different from the migration of Europeans in the previous century.

The Global Nurse Workforce

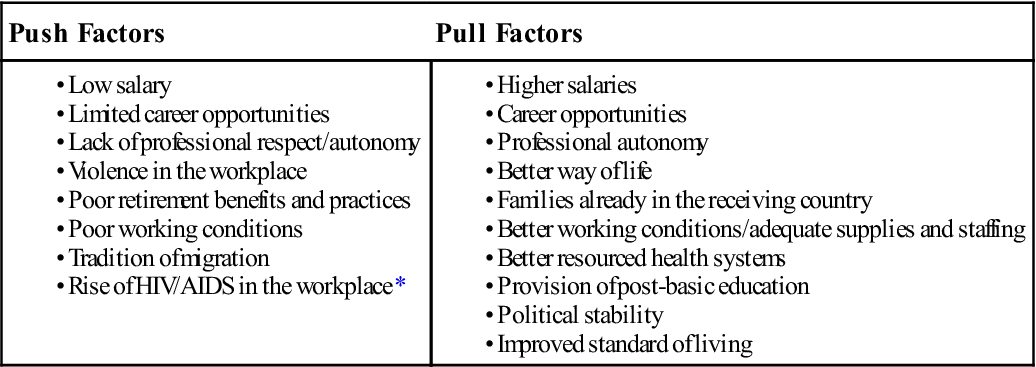

A number of “push” factors (reasons for leaving one’s own country) and “pull” factors (reason for choosing a receiving country) motivate nurses to migrate. Some countries, despite their own domestic health care needs, cannot create enough jobs to employ the nurses they educate. Policies and restrictions related to pay and career structure, retention, recruitment, deployment, transfer, promotion, and the planning framework are other factors that “push” nurses to leave (Vujicic, Ohiri, & Sparkes, 2009).

Governmental policies on return migration and remittances also encourage nurses to seek employment in other countries. Return migration enables the source country to benefit from the skills acquired by the nurse while working in another country and thus provides an incentive for nurse migration. Remittance refers to the portion of an immigrant’s income that returns to the source country in the form of either funds or goods. The World Bank estimates that global remittances reached $328 billion in 2008 (Orozco & Ferro, 2009). Nurses are more likely to be remitters than other migrants, remitting $8 billion to the Philippines and $5 billion to India in 2008. Remittances, which are the second most important source of external funding for developing countries (after direct investment), are generally used to provide financial support, decrease poverty, and improve education and health for families back home (Focus Migration, 2006).

Factors that “pull” nurses to developed countries include higher wages, improved living and working conditions, and opportunities for advancing their education and clinical skills. The continuing existence of gender-based discrimination in many cultures and countries, with nursing being undervalued as “women’s work” relative to other professions, also encourages nurses to migrate. Table 52-1 presents the common push/pull factors that precipitate global nurse migration.

TABLE 52-1

Common Push/Pull Factors That Precipitate Global Nurse Migration

| Push Factors | Pull Factors |

A migration-related issue that has received increasing attention is the effect of international nurse recruitment on local and global health care needs. When the U.S. nursing shortage exploded, so did the shortages in Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), and Australia. More troubling, many developing countries were experiencing nursing and physician shortages concomitantly with critical health challenges, such as HIV disease, infant mortality, and other public health problems. The developed countries encountered global criticism because they were accepting foreign-educated nurses from countries that needed nurses to meet their own health care needs. The question of how to balance the right of nurses to migrate for their own personal and professional reasons and the needs of people in both the source and receiving countries is still unanswered. Some receiving countries, such as the UK, have issued agreements with source countries, such as South Africa, to limit their recruitment in that country. Others have provided scholarships and educational funding with the intent to replenish the source countries’ supply of nurses. Return migration upgrades a country’s nursing workforce.

Trends in U.S. Nurse Migration

The U.S. is one of the top receiving countries for migrating nurses. Foreign-educated nurses entering the U.S. workforce tend to be female, 30 to 35 years of age, and educated in baccalaureate programs. Generally, they have worked for 1 to 5 years in their home countries prior to migrating. When practicing in the U.S., the majority work in hospital settings (critical care and adult health), with long-term care being the second venue of choice (CGFNS, 2002).

Source countries that traditionally have provided nurses to the U.S. are the Philippines, Canada, and India. This pattern continues today and is augmented by emerging suppliers such as China, South Korea, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Caribbean. Foreign-educated nurses can be found in all areas of the country; however, five states receive the majority of migrating nurses (California, New York, Texas, Florida, and Illinois), though other states have begun seeing an increase—most notably Georgia and North Carolina.

In 1994, foreign-born nurses made up 9% of the U.S. workforce, but, by 2008, this percentage had increased to 16.3% (Buerhaus, Auerbach, & Staiger, 2009). It should be noted that “foreign-born” does not mean that the individual also was educated outside the U.S. Many foreign-born students enter the U.S. on a student visa to attend nursing school and then either return home or adjust their visa status to permanent and become part of the U.S. workforce. Initial findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN) indicate an increase in foreign-educated nurses in the workforce from 3.7% in 2004 to 5.6% in 2008, despite periods of retrogression implemented by the U.S. State Department (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], 2010).

Retrogression

Retrogression, the procedural delay in issuing visas when more visa applications have been received than visa slots exist, has limited the number of foreign-educated nurses who can obtain occupational visas to practice in the U.S. The Department of State determines when it is necessary to impose limits on the allocation of immigrant visas and to which countries retrogression will apply. Under retrogression, visa applications are not processed until the backlog is completed (Richardson & Davis, 2009). When retrogression was ordered in 2004, it applied only to China, India, and the Philippines and lasted for several months. The most recent retrogression (November 2006) was for all countries and continues as of 2010, causing a major decrease in the recruitment and visa certification of foreign-educated nurses (Richardson & Davis, 2009). A source country’s economy may be dependent on how many of its citizens work overseas—a fact that fuels the push for changes in U.S. immigration and economic policies, which are needed to open the doors closed by retrogression and the downturn in the U.S. economy.

Policy Implications for the U.S. Nursing Workforce

Imbalances in nurse staffing vary among nations, regions, states, levels of care, specialties, and organizations. The dynamics of supply and demand driven by an aging population, increasing demands for health care, and migration are out of balance with the growing global shortage. Nursing shortages are often a symptom of wider health system and societal elements. For sustainable solutions, it is not about just numbers of nurses but whether or not the health system enables nurses to use their skills effectively. Aiken and colleagues (2004) argued that “developed countries’ growing dependence on foreign trained nurses is largely a symptom of failed policies and underinvestment in nursing.”

Receiving countries have the following four major policy challenges:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree