Chapter 1 The global midwife

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Challenges in global midwifery for the 21st century

Midwives originating from the West will hold very different perspectives of childbirth and midwifery practice compared with colleagues from other countries, especially those classified as less and least developed (WHO 2007). Midwives worldwide aim to provide a safe environment for birth. However, countless women in today’s world are forced to experience childbirth, not as a fulfilling experience, but as one fraught with fear and danger. In the 21st century, a majority of women still cannot dissociate birth from death. Consequently, midwives are challenged to play a leading part in making childbirth safer. Of the 130 million babies born worldwide each year, it is estimated that almost 8 million die before their first birthday, 4 million in the first month of life (WHO 2006a).

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (see website) include efforts to improve the health of both women and children, particularly in the context of poverty and disease (Box 1.1). Making pregnancy safer challenges not only health professionals, but also technical experts, including water engineers, road builders, telecommunication experts and vehicle mechanics. Community mobilization even in the farthest reaches of the globe needs to find resonance in political will at the highest levels.

Contrasts and inequalities

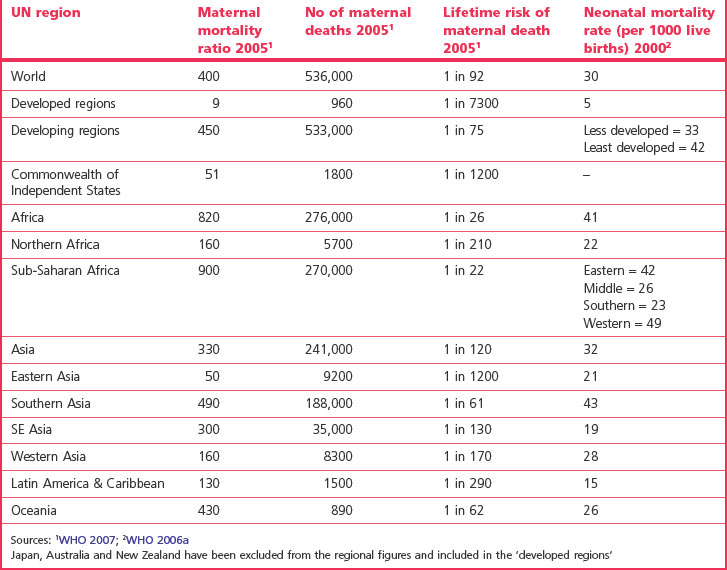

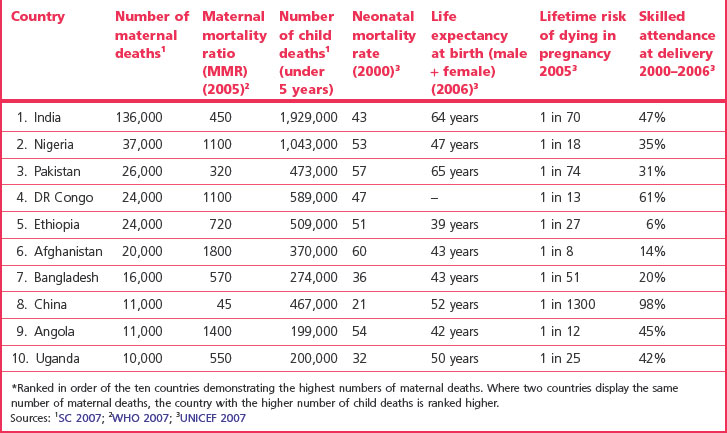

It has been stressed that one of the most striking measurable contrasts between industrialized and developing countries becomes evident in examining maternal mortality ratios. The 2005 estimates confirm the highest figures in sub-Saharan Africa followed by South Asia (Table 1.1). Globally, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) (see Ch. 16) reduction has proceeded on average by 1% between 1990 and 2005. MMR, as a key indicator for MDG 5 (Box 1.1), needs to decrease at a much faster rate if this goal is to be met (WHO 2007).

On a global scale, it is estimated that every minute of every day, a woman dies of pregnancy-related complications; the massive death toll exceeds half a million each year (WHO 2008a); 99% of these deaths occur in developing countries, figures varying considerably (Table 1.1). Motherless newborns are between 3 and 10 times more likely to die than those whose mothers survive (UNICEF 2008a).

Causes of maternal death

Main causes

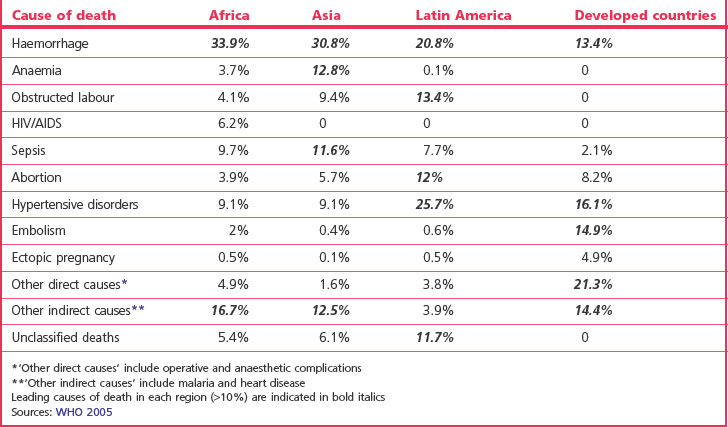

In developing countries, maternal death is the second most common cause of death after HIV/AIDS. There are five main obstetric causes of maternal death worldwide: haemorrhage, infection, unsafe abortion, hypertensive disorders and obstructed labour (WHO 2008a). Haemorrhage accounts for around a quarter of deaths globally. However, the leading cause of death tends to vary with the region (see Table 1.2). In many countries, adolescent mothers are twice as likely to die as other pregnant women (WHO 2008a) (see Ch. 16).

Predisposing factors

Maternal death is influenced by numerous factors. The reasons why women die have been described as ‘many layered’ (AbouZahr & Royston 1991). These layers include social, cultural and political factors that determine crucial issues including the status of women, women’s health and fertility, and their ‘health-seeking behaviour’. Failures in healthcare systems and transportation add to the problems.

One of the issues confronting an estimated 100–140 million women and girls each year is female genital mutilation (FGM) (see website and Ch. 58). The United Nations agencies are committed to addressing this practice which violates the human rights of a person (WHO 2008a).

Although sub-Saharan Africa accommodates just over 10% of the world population, 63% of all HIV infections are evident there (UNAIDS/WHO 2006). Linkage between HIV and maternal mortality has been established in the region (DFID 2005). Malaria kills more than a million each year and pregnant women and their unborn children are particularly vulnerable, placing them at risk for low birthweight and anaemia (UNICEF 2007). HIV is thought to increase the susceptibility of multigravid women to pregnancy-associated malaria (Keen et al 2007).

In addition to the 1500 women who die daily due to pregnancy-related causes, 10,000 newborn babies die, and it is estimated that most of these deaths could be prevented through skilled care during childbirth and the management of life-threatening complications (WHO 2008b). Whereas more than 99% of births are attended by skilled personnel in the most developed countries, this reduces to 59% and 34% respectively in the less and least developed countries (WHO 2007). It is estimated that mortality and morbidity in the perinatal and neonatal periods are caused mainly by preventable or treatable conditions (WHO 2006a). Infections, including pneumonia and neonatal tetanus, asphyxia, preterm birth and congenital anomalies contribute to 36% of the global deaths in children under 5 years (UNICEF 2007).

Maternal morbidity

Morbidity is less easily measurable. It is estimated that of the 136 million women who give birth each year, 20 million suffer pregnancy-related illness (WHO 2008a). The term ‘severe acute maternal morbidity’ (SAMM) has recently entered obstetric literature; several definitions include the concept of ‘near-miss’ and a situation where pregnancy-related complications lead to the failure of body organs. Utilizing the latter concept, it has been estimated that 4–8% of women in resource-poor areas will experience SAMM, compared with 1% in more developed areas (WHO 2005). Horrific injuries such as obstetric fistulae (see website), stigmatizing women in their families and communities, have been described as one of the most visible indicators of the massive gaps in maternal healthcare between the developing and developed world (WHO 2006b). Other morbidities include anaemia, infertility and depression.

Inequalities associated with being a mother

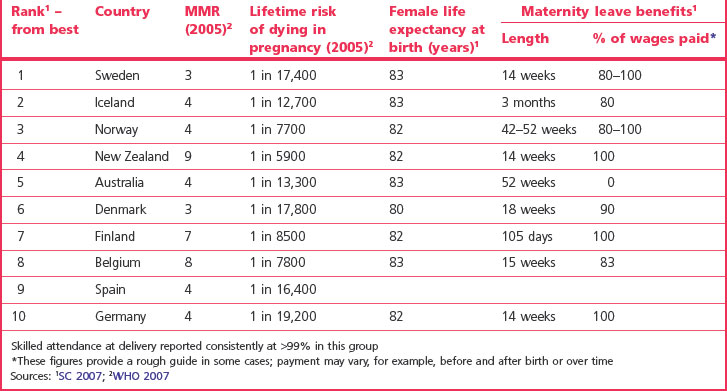

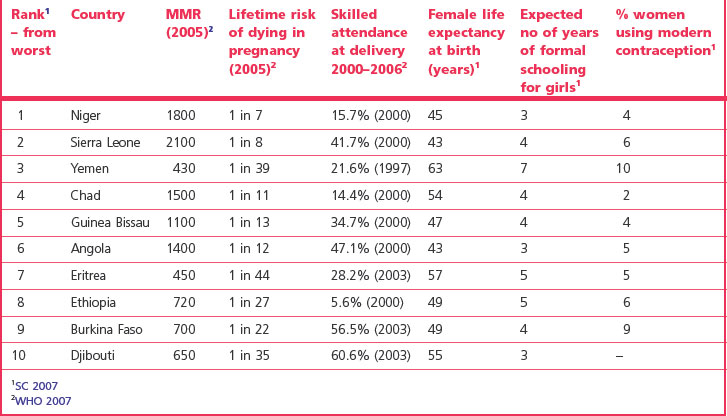

The experience of childbearing can be vastly different depending on the country of residence. Comparisons of data in Tables 1.3 and 1.4 provide insight into some of the major factors affecting women in the 21st century.

The highest numbers of women and children who die are evident in India, Nigeria and Pakistan, and the 10 countries listed in Table 1.5 contribute to the majority of global maternal and neonatal deaths.

Table 1.5 The top ten countries* with the highest numbers of maternal and child deaths (representing approximately 60% of the global MMR & NMR totals)

The Safe Motherhood Initiative

It was estimated that 88–98% of all maternal deaths could ‘probably have been avoided’ (WHO 1986). Consequently, the Safe Motherhood Initiative was inaugurated in 1987 with the aim of reducing maternal mortality and morbidity by 50% by 2000 (SMI 1987).

Action messages agreed by Safe Motherhood Partners in 1997, setting priorities for the next decade (Box 1.2), find resonance today in the MDGs, including the current emphasis on safe motherhood and human rights. In order to work towards the MDGs (Box 1.1), many governments have committed to reducing poverty and promoting human rights when providing aid to the developing world (DFID 2006, Sveriges Riksdag 2005).