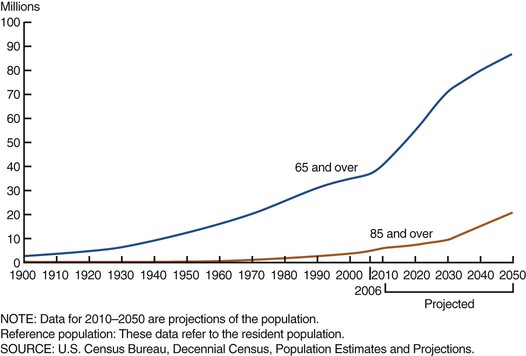

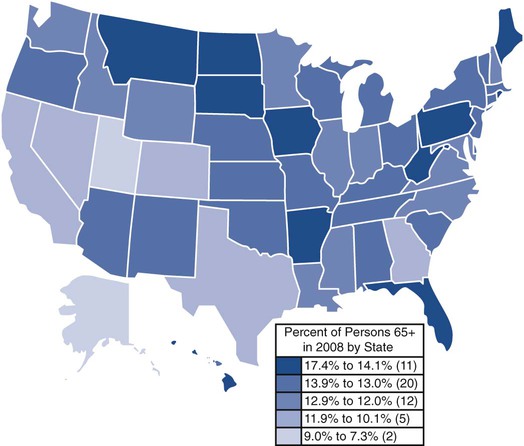

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Specify demographic changes related to the aging experience in the twenty-first century. 2. Understand the many factors that facilitate or hinder the aging process. 3. Recognize the great diversity of older adults. 4. Discuss strategies to prepare an adequate and competent eldercare workforce to meet the needs of the growing numbers of older people. 5. Identify several factors that have influenced the development of gerontological nursing as a specialty practice. 6. Discuss several formal geriatric organizations and their significance to nurses. 7. Compare various gerontological nursing roles and requirements. 8. Discuss nursing research studies on the care of older adults and the role of gerontological nurses in research. In the past, healthy older men and women frequently eluded the attention of gerontologists. Thus study samples of the elder adults, most likely taken from institutionalized subjects, were often extrapolated to the healthier population. This led to a picture of aging that viewed older people as frail and dependent with little to look forward to in the last years of life. To some extent, that view of aging remains today and is steeped in the myths perpetuated about older adults. Older people are often viewed as ill, lonely, depressed, abandoned by family, a burden to society, just waiting to die. The reality is that the majority of those aged 65 and older regard their health as good or excellent; increasing numbers are extending their active working lives into their 70s and 80s; many have close and meaningful relationships with their families in parent, grandparent and great-grandparent roles; and the number of people living to 100 years of age is projected to grow at more than 20 times the rate of the total population by 2050. The developmental period of elderhood is an essential part of a healthy society and as important as childhood or adulthood (Thomas, 2004). We can expect to spend 40 or more years as older adults, and our preparation for this time in our lives certainly demands attention as well as expert care. How does one maximize the experience of aging and enrich the years of elderhood regardless of the physical and psychological changes that commonly occur? Nurses have a great responsibility to help shape a world in which older people can thrive and grow, not merely survive. Most nurses care for older people during the course of their careers. In addition, the public will look to nurses to have the knowledge and skills to assist people to age in health. Every older person should expect care provided by nurses with competence in gerontological nursing. Gerontological nursing is not for someone else or only for a specialty group of nurses. Knowledge of aging and gerontological nursing is core knowledge for the profession of nursing (Young, 2003). How nurses move our aging society forward toward the middle of the twenty-first century will determine our character, as we are no greater than the health of America. That is what this textbook is all about. Words, statistics, and research data can only paint a picture of how aging looks. The most significant learning regarding the intricacies and challenges of aging and survival strategies comes from discussions with elders themselves. They are our role models, and their diversity makes it possible for us to develop a greater understanding of life if we only listen to what they say and that which is unsaid. Many years ago, Irene Burnside (1975), one of the geriatric nursing pioneers, said it beautifully: The term geriatrics was coined by an American physician, Ignatz Nascher, around 1900 because he recognized that the medical care of older people involved special considerations, much like the field of pediatrics. Nascher authored the first textbook on medical care of the elderly in the United States in 1914 (Nascher, 1914). Aging has been seen as a biomedical problem that must be reversed, eradicated, or held at bay as long as possible. Therefore, the impact of disease, morbidity, and impending death on the quality of life and the experience of aging have provided the impetus for much of the study by gerontologists. In this way, aging has inevitably been seen through the distorted lens of disease. However, we are finally recognizing that aging and disease are separate entities although frequent companions. The trend toward the medicalization of the study of aging has influenced the general public as well. The biomedical view of the “problem” of aging is reinforced on all sides. A shift in the view of aging to one that centers on the potential for health, wholeness, and quality of life, and the significant contributions of older people to society, is increasingly the focus in the research, popular literature, and public portrayals of older people. Centenarians, the “elite-old,” are approached with some awe as our society seeks routes to longevity. The number of centenarians in the United States has doubled every decade since 1970, and they are the fastest growing segment of our population. One in 26 Americans can expect to live to be 100 by 2025, compared with only one in 500 in 2000 (Administration on Aging, 2009). There are 221,500 supercentenarians (those older than 110). Many of the “elite-old” are bright and alert and have an unequaled personal history. However, although centenarians appear to be healthy for a longer period of time, almost 50% live in nursing homes. In part this may be due to the absence of living children, siblings, or spouses (Hooyman and Kiyak, 2011). Most centenarians are female (85%) and come from families in which longevity is common. Although there are fewer male centenarians, they are less likely than women to have significant mental or physical disabilities at that age, and older men who survive to age 90 represent the hardiest segment of their birth cohort (Christensen, 2001; Hooyman and Kiyak, 2011). Persons of color who live to age 85 are “hardier” than their white counterparts (racial crossover effect). Thirty percent of centenarians have no evidence of dementia (Silver et al., 2001). They are often sought for their opinions on the key to longevity. The supposition is that because they have lived so long they know the secrets to learning, growing, and thriving. Various centenarians have recommended such things as a daily highball, hard work, church attendance, healthy diets, or the continuation of sexual activity. Unfortunately, few agree and the myths abound. Lifestyle factors that do seem significant include diet, maintaining proper weight, exercise, avoidance of smoking, social connections, and how well a person handles stress (Mentes, 2006). Researchers all over the world are studying centenarians. Many questions and conflicting findings still exist regarding both the physiological and psychological adaptation of centenarians. Several websites offer a fascinating look at centenarians, including pictures: http://www.adlercentenarians.org/ and http://www.grg.org/calment.html. To plan well for their retirement years, we must consider the following: • The uncertain political and economic future • Potential major shifts in lifestyle expectations • Changing health care delivery and reimbursement systems • Progress in technology and medical management • Shifts in values and ethics that will profoundly affect daily life Articles about menopause proliferate, midlife crises abound, and anxiety about the future is rampant. Will there be income support, adequate retirement, available health care, disability benefits, and all the things the present generation of the old have relied on? The major concerns of baby boomers are health, finances, job security, sending children to college, and caring for parents. They have been called the “sandwich generation,” because they try to meet the needs of “boomerang” children (those young adults who repeatedly return home because they cannot generate sufficient incomes to live independently) and elderly parents. Shirley Chater (a nurse and a former director of Social Security) called them the “double whopper” generation. “Triple whopper” is probably more accurate today, because many older people are also the primary caretakers of grandchildren. Gerontologists, marketing strategists, and the age industry are attempting to predict anticipated challenges. Many uncertainties remain about the conditions, status, and benefits baby boomers will experience. Some of the major concerns are based on the shift of lifestyles away from the traditional family. Single parents, blended families, limited parenthood, unmarried parents, and gay and lesbian parents all represent lifestyles that may or may not produce children willing or available to assist parents as they age (see Chapter 22 for further discussion of caregiving roles and responsibilities). The 2010 total population of the United States was 308,745,538. Of these, almost 38 million are older than 65 years, making up 12.6% of the population. Of these, 42.2% are older men and 57.8% are older women. By 2030, almost 1 in 5 Americans (72 million people) will be 65 years or older. The age group 85 years and older is now the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population (Figure 1-1). At present, about 0.0173% of the population are at least 100 years old, compared with 0.1% in 1901 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). The total number is expected to increase by more than 400% by 2030. The majority of these centenarians will be women (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). An American’s average life expectancy at birth has trended upward as a result of reduced death rates for children and young adults, new drugs, medical technology, and better disease prevention. Between 1985 and 2005, the death rates for the population aged 65 to 84 dropped, especially for men. For men aged 65 to 74, the death rate has dropped by 32.3% and by 23.5% for men aged 75 to 84. Life expectancy at age 65 increased by only 2.5 years between 1900 and 1960 but has increased by 4.2 years from 1960 to 2007 (Administration on Aging, 2009). In 2010, the life expectancy for infant girls in the United States was 80.8 years, whereas for boys it was 75.7 years. However, among African-Americans, life expectancy was 70.2 years for men and 77.2 years for women, evidence of an important health disparity (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010) (Figure 1-2). Hispanics in the United States outlive whites by 2.5 years and blacks by nearly 8 years (CDC, 2010). A 2008 report comparing the United States with 18 other industrialized countries reported that in 2002-2004, the United States had among the highest death rates from causes amenable to health care of the countries studied. The report attributed the slow decline in U.S. amenable mortality to the increase in the uninsured population (American Medical Association, 2008). The majority of people over the age of 80 live independently in the community. Older men are more likely to be married than older women, and 42% of all older women are widowed. There are more than four times as many widows as widowers (Figure 1-3). The number of older people who are divorced or separated is increasing and can be expected to rise as the baby boomers age. In the United States, 39% of women and 19% of men over the age of 65 live alone (Figure 1-4). Florida has the highest proportion of people over the age of 65 (17.6%) followed by West Virginia (15.7%), Pennsylvania (15.3%), Maine (15.1%), and Iowa (14.8%). Between 1998 and 2008, the 65 years-and-older population increased 25% or more in Alaska, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, Idaho, Georgia, South Carolina, Colorado, and Delaware (Administration on Aging, 2009) (Figure 1-5). Most persons 65 years of age and older live in metropolitan areas (80.6%) (Administration on Aging, 2009). In the comparatively mobile population of the United States, the experience of aging is greatly influenced by where one lives. The educational level of the older population is increasing (Figure 1-6). Between 1970 and 2008, the percentage of older persons who had completed high school rose from 28% to 77.4%. In 2008, about 20.5% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Completion of high school varies considerably by race and ethnic origin: 82.3% of the white population, 73.9% of Asians and Pacific Islanders, 59.7% of African Americans, and 45.9% of Hispanics. However, the increase in educational levels is also evident within these groups. In 1970, only 30% of older white individuals and 9% of African Americans had completed high school (Administration on Aging, 2009). The baby boomers, and people currently 65 to 69 years of age, are more educated than the current old-old and future generations will continue this educational trend. In 2008 households headed by persons 65 and over reported a median income of $44,188. Median income varies as follows by race and culture: $46,527 for non-Hispanic whites, $32,901 for Hispanics, $35,025 for African Americans, and $38,859 for Asians. The percentage of people living below the poverty level was 9.7% in 2008. However, a recent report by the Alliance for Children and Families (2010) notes that 18% of Americans will have experienced poverty by the age of 70, 29% by the age of 80, and 41% by the age of 90. Longer life expectancies, fluctuating economic conditions, and rising health care costs contribute to increasing concerns about poverty in old age in this country. Gender, racial, and cultural disparities exist. One of every 14 older white individuals was poor in 2008, compared with 20% of older African Americans and 19.3% of Hispanics. Women make up 6 or the 10 older people at risk or already living in poverty (Alliance for Children and Families, 2010). The highest poverty rates were experienced by older Hispanic women (43%) and older African American women (34.7%) who lived alone. Women, particularly culturally and ethnically diverse women, face great challenges as they age. The United States has one of the highest poverty rates for older women among industrialized countries. The problems of aging are largely problems of older women. Factors influencing the poverty status of older women include pay inequity, occupational segregation, caregiving responsibilities, longer life expectancy, rising health care costs, and women’s work patterns, all of which reduce pension earnings, public assistance benefits, and personal savings (Hounsell and Riojas, 2006). An increasing number of people over the age of 65 are remaining in or returning to the workforce. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of people age 55 to 64 who are working is expected to climb by 36.5%. The number of workers over the age of 75 will rise by more than 80% during that time period. By 2016, workers over the age of 65 will account for 6.1% of the total labor force, up sharply from their 2006 rate of 3.6%. Some of this is because of a desire to continue their careers but is more frequently out of economic necessity (Administration on Aging, 2009; Hooyman and Kiyak, 2011) (Figure 1-7). Racially and culturally diverse older people make up about 19% of all older Americans. This is projected to increase to approximately 40% by 2050. Most of this growth in racially and culturally diverse Americans is a result of patterns of immigration and higher fertility rates. The number of African-American elders will increase by 128%; the population of Asian-American elders will increase by 301%; Hispanic-American elders will grow 322%; and Native Americans and Alaska Native elders will increase by about 193%. By 2050, the percentage of the older population that is non-Hispanic white is expected to decline from 84% to 64%. Among all ethnic and racial groups, the Hispanic older population is projected to grow the fastest, from about 2 million in 2000 to more than 13 million by 2050 (Figure 1-8). The fastest growth will occur in those 85 years of age and older. By midcentury, groups that have historically been called minorities will become the majority in most states (Administration on Aging, 2009; Hooyman and Kiyak, 2011). Although the health status of racial and ethnic groups has improved over the past century, disparities in major health indicators between white and nonwhite groups are growing. Increasing the numbers of health care providers from different cultures and ensuring cultural competence of all providers is essential to meet the needs of a rapidly growing, ethnically diverse elderly population. Chapter 5 discusses gender and cultural issues in aging in more detail. Japan (82.6 years), Hong Kong (82.6 years), Hong Kong (82.2), Iceland (81.8 years), and Switzerland (81.7 years) have the longest life expectancy. Of course, these statistics are influenced by the infant mortality rates, which are lowest in Sweden, Iceland, Japan, and Singapore. The United States has a higher infant mortality rate than 28 other countries and ranks 38th in life expectancy at birth (Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, 2009). In 2010, the infant mortality rate in the United States, which has been at the same level for years, dropped about 2% to a record low of 6.59 deaths per 1,000 births. However, the rate for black infants is about twice that of whites (Minino, Xu, Kochanek, 2010). Experts predict that the number of older people in the developing world will double in the next 20 years. In 2015, 67% of the world’s older people will live in developing countries (Figure 1-9). Older people in developed and developing countries face different challenges as they age. James Martin, in an address to the International Federation on Aging in 2006, calls this a century of extremes. In the United States, we are studying regenerative medicine and predicting that people could live to 120 years, whereas in Botswana, life expectancy is 27 years. Around the world, 100 million older people live on $1 or less per day. Poverty, hunger, and lack of access to basic life necessities are all too common in developing countries for people of all ages. Of older people in developing countries, 80% have no regular income, lack of food is a serious cause of ill health, and older widows are among the poorest and most vulnerable groups. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic has had devastating economic, social, physical, and psychological effects on older women and men, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Almost 13 million children have lost one or both parents to HIV/AIDS, the vast majority in sub-Saharan Africa. As many as 9 of 10 orphans are cared for by their extended family, mainly the grandparents (see www.helpage.org). As we study how to care for older people, it is important to remember that our view must be expanded to include older people across the globe, who have very different needs. More details on international aging can be found in the International Plan of Action on Ageing (available at http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/madrid_intlplanaction.html). America’s eldercare workforce is dangerously understaffed and unprepared to care for the growing numbers of older adults. The demand for gerontological nurses and other health professionals, as well as direct care staff, prepared to deliver care in all settings is critical. Older adults are the core consumers of health care, with higher rates of outpatient provider visits, hospitalizations, home care, and long-term care service use than other age groups. Eldercare is projected to be the fastest growing employment sector in the health care industry. In spite of demand, the number of health care workers who are interested and prepared to care for older people remains low (Institute of Medicine, 2008). Less than 1% of registered nurses and only 6% of advanced practice nurses are certified in gerontology (Mezey et al., 2004). Geriatric medicine faces similar challenges with just 7,128 geriatricians, one for every 2,546 older Americans. By 2030, it is estimated that this number will increase to only 7,750, one for every 4,254 older Americans, far short of the predicted need for 36,000 (Institute of Medicine, 2008). Other professions such as social work have similar shortages. The Eldercare Workforce Alliance, a group of 28 national organizations representing older adults and the eldercare workforce, including family caregivers, health care professionals, and direct care workers, has begun to address these concerns. Immediate goals of the Alliance are to strengthen the direct care workforce through better training, supervision, and improved compensation; address clinician and faculty shortages through incentives such as loan forgiveness, increased public funding for training, and better compensation; ensure a competent workforce by encouraging agencies and organizations that certify and regulate the eldercare workforce to require demonstrated and continued competence; and redesign health care delivery by adopting cost-effective care coordination models (www.eldercareworkforce.org/). Improving the competency and adequacy of the eldercare workforce is essential to meet the needs and demands of a burgeoning aging population. “The consequences of inaction will be profound” (American Geriatrics Society, 2005, p. S246).

Gerontological Nursing and an Aging Society

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

The Study of Aging

Gerontology

Today’s Older People

Nonagenarians and Centenarians

The Future Old

Aging Today

Aging in the United States

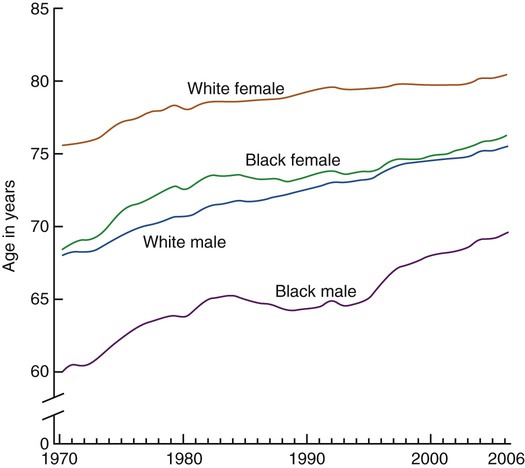

Life Expectancy

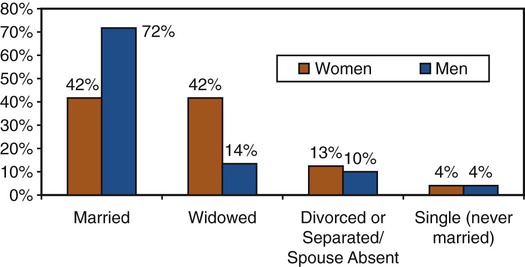

Marital Status

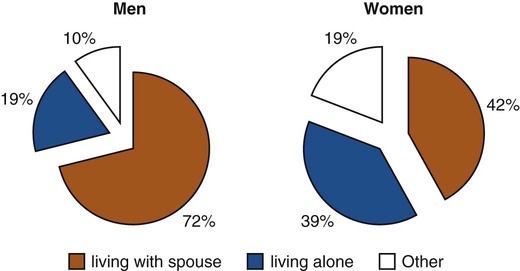

Living Arrangements

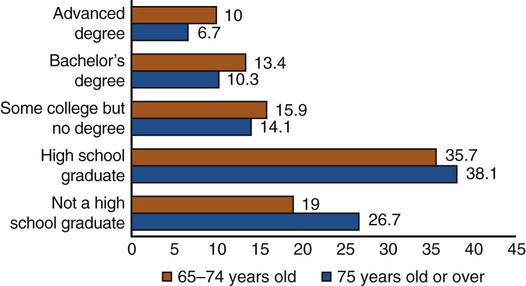

Education

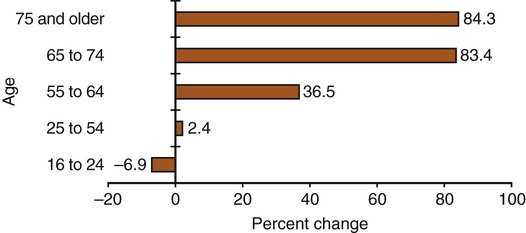

Income and Employment

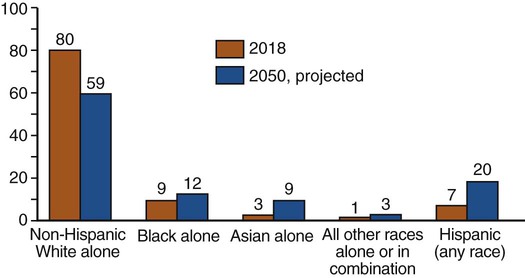

Diversity of Aging in the United States

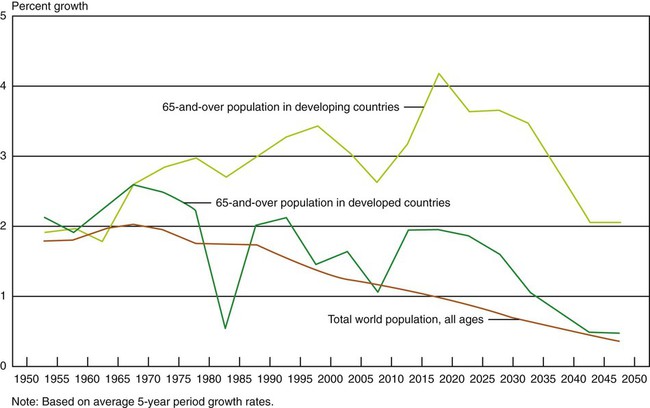

Global Aging

Who Will Care for an Aging Society?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access