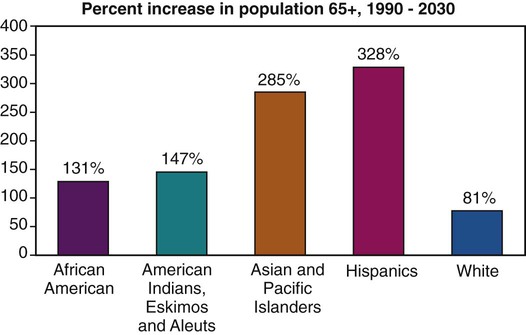

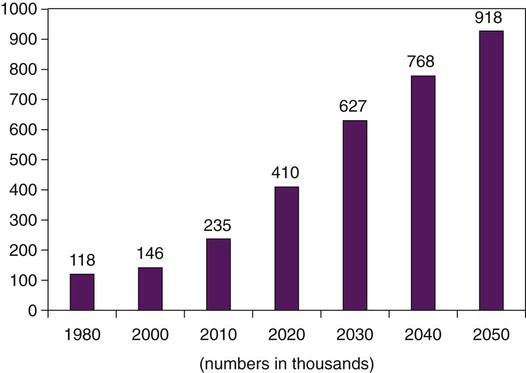

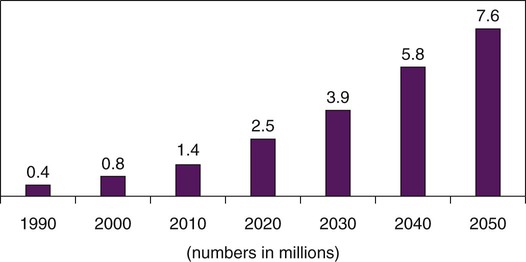

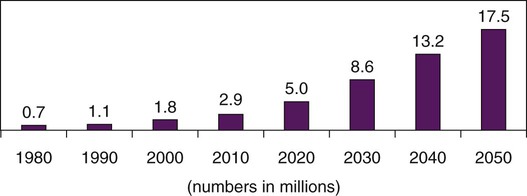

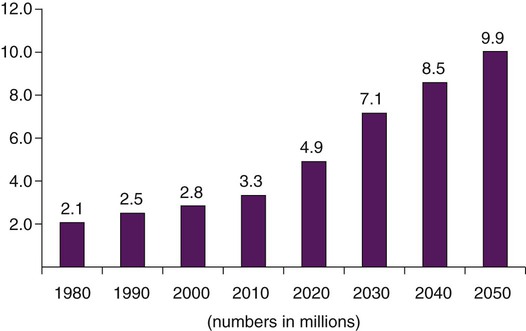

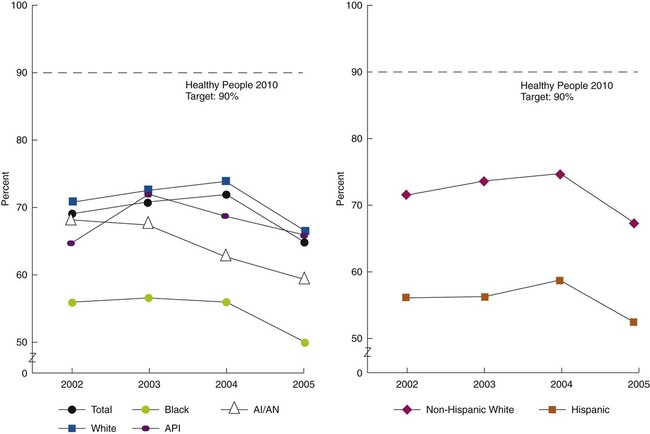

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Recognize the current knowledge related to health disparities and their potential impact on older adults of color and women. 2. Relate major historical events that have affected each cohort of elders. 3. Compare several different ethnically based approaches to health care. 4. Describe several of the unique circumstances related to gender and aging. 5. Identify personal factors contributing to ethnic and cultural sensitivity. 6. Discuss approaches that facilitate an appreciation of diverse cultural and ethnic experiences. 7. Accurately identify situations in which expert interpretation is necessary. 8. Understand key points of working with interpreters. 9. Formulate a care plan incorporating ethnically sensitive interventions. 10. Develop gerontological nursing interventions geared toward reducing health disparities. Interest in and attention to culture and gender issues in health care are increasing. This interest is stimulated to a great extent by the realization of a demographic imperative and the recognition of the significant health disparities and inequities in the United States. The demographic imperative refers to the significant increases in both the total numbers of older adults and the relative proportion of older adults in most countries across the globe. These numbers reflect a “gerontological explosion” of older adults from ethnically distinct groups (Figure 5-1). This chapter provides an overview of culture, gender, and aging, as well as strategies gerontological nurses can use to best respond to the changing face of elders and, in doing so, help reduce health disparities and promote social justice (see http://www.apha.org/meetings/highlights/Theme.htm). These strategies include increasing cultural sensitivity, knowledge, and skills in working with diverse groups of older adults. In the United States, the percentage of persons of racial or ethnic groups other than white European has increased significantly. It is projected that by 2050 persons from groups that have long been counted as statistical minorities will assume membership in what can be called the emerging majority. Although not yet a majority, those persons from minority groups who are at least 65 years of age will increase from 20% to 42%; among those at least 85, the numbers will increase from 15% in 2010 to 33% in 2050 (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). When projected to 2050 there will be some significant shifts in the percentage share among all racial and ethnic groups as well as those of mixed race in the ≥65 population. For example, those who report “white alone” will decrease from 87% to 77%; black alone will increase from 9% to 12% between 2010 and 2050 (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). Other groups will double or triple their current numbers. The greatest period of growth will be between 2010 and 2030. For a group-to-group comparison in growth see Box 5-1 through Box 5-4. It must be noted, however, that these and many of the figures available today are drawn from the U.S. Census, in which persons of color are often underrepresented and those who reside illegally are not included at all. In reality, the number of ethnic elders in the United States may be or will become substantially higher. Adding to the diversity in the United States is the number of persons emigrating from other countries; the rate at which this number is growing exceeds that of the native born. Although access to the United States varies with global politics, older adults are continually being reunited with their adult offspring, whom they assist with homemaking and care for younger children in the family as they are cared for themselves. It is becoming increasingly common for communities to provide and support senior centers with activities and meals reflective of their diverse participants. The diversity of values, beliefs, languages, and historic life experiences of elders today challenges nurses to gain new awareness, knowledge, and skills to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate care. Nurses practicing in those areas with the most diversity (California, New York, and Texas) are highly likely to care for persons from a variety of backgrounds in the same day and a culture other than their own (Administration on Aging, 2010). The document Healthy People has served as a guide for the promotion of health and the prevention of disease and disability since it was first published in 1979 and updated in 2000. It is in the process of revision in 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009a). In the past, one of the goals was to decrease health disparities. At present one of the new overarching goals goes much further: “Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups” (USDHHS, 2009b) (Box 5-5). This goal and its associated objectives have significant implications for the consideration of culture, gender, and aging and for the practice of gerontological nursing. Addressing health disparities begins with providing culturally competent and proficient care. The result of the study was that, even when controlling for unequal access, health care treatment in and of itself was unequal (Smedley et al., 2002). The barriers to quality care were found to be wide, ranging from those related to geographical location to age, gender, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Disparities were consistently found across a wide range of disease areas and clinical services. Among the findings were the following: • Disparities were found even when clinical factors, such as stage of disease presentation, comorbidities, age, and severity of disease, were taken into account. • Disparities were found across a range of clinical settings, including public and private hospitals and teaching and nonteaching hospitals. • Disparities in care were associated with higher mortality among minorities. In the years since then, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Rockville, MD) has produced national healthcare quality reports and national healthcare disparities reports to track the prevailing trends in health care quality and access for vulnerable populations, including the elderly and those from minority populations. Each year another aspect of care is highlighted. Most of the information available consists of comparisons between the white and black populations. There is still inadequate data available about other groups, e.g., Native Alaskans for an adequate assessment of their health care status (Table 5-1 and Figure 5-2). None-the-less older adults of color have been described as facing “double jeopardy” for health disparities because of two risk factors for vulnerability (age and ethnicity). For black women, the risk becomes “triple jeopardy,” and poverty adds a fourth factor. TABLE 5-1 BLACKS COMPARED WITH WHITES ON MEASURES OF QUALITY AND ACCESS FOR MOST CURRENT DATA YEAR: SPECIFIC MEASURES, 2009* AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. *Modified for those most relevant to older adults. From Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research: Priority populations: older adults. In: National healthcare quality report, 2009. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr09/Chap4.htm. Accessed December 2010. The development of cultural proficiency begins with increased awareness of our own beliefs and attitudes and those commonly seen in the community at large and in the community of health care (Box 5-6). Increased awareness requires openness and self-reflection. Consider the following: If the nurse is white, it is realizing that whiteness alone often means special privilege and freedoms. Older adults of color may not have had the same advantages or experiences as the nurse (McIntosh, 1989). Cultural awareness means recognizing the presence of the “isms” (e.g., racism, social classism, ageism) and how these have the potential to impact not only health care but also the quality of life for older adults (Smedley et al., 2002). Awareness includes considering how the nurse feels about gender. For example, is sexuality accepted in the same way in older men as in older women? Cultural knowledge includes the appropriate use of terms, especially race, culture, and ethnicity. Often used interchangeably, each actually has a separate meaning. Race is defined in terms of phenotype as expressed in traits, such as eye color, facial structure, hair texture, and especially skin tones. In a genomic analysis of persons identified as member of a racial group there is little difference. The term “race” is best used as a proxy for geographic origins and lineage with implications for pharmacogenomics more than anything else (see Chapter 9). However, the relative usefulness of race is diminishing because of widespread mixing of the gene pool, making it increasingly uncommon for any one person to be genetically homogeneous (Gelfand, 2003). Acknowledgment of this heterogeneity was demonstrated when a new racial category of “mixed” was added to the 2000 U.S. Census forms. Culture is the shared and learned beliefs, expectations, and behaviors of a group of people. Style of dress, food preferences, language, and social behavior are reflections of culture. Culture guides thinking, decision-making, and action. Beliefs about aging may be relatively consistent within one culture group (Jett, 2003). Cultural beliefs about aging are often portrayed in the media, both in print and on the screen. For example, the 2005 movie In Her Shoes portrays a number of white stereotypes about aging, both positive and negative. A particular characteristic of culture is that it is transmitted from one member to another through a process called enculturation. Culture provides directions for individuals as they interact with family and friends within the same group. Culture allows members of the group to predict each other’s behavior and respond in ways that are considered appropriate (Spector, 2008). Acculturation is the process by which a person from a minority or marginalized culture adopts that of the dominant or majority culture in which they find themselves. There has been much concern about aging immigrants and how culture facilitates or hinders the adjustments needed in late life in the United States. Pierce and colleagues (1978/1979) and Spector (2008) wrote that various types of acculturation were more critical to functional adaptation than others. For example, outward adaptation that incorporates language, dress, and behavior was seen as superficially important. On a deeper level, traditional personal value orientations, including concepts of time, and personal relationships to others and nature, were more likely to remain in the original cultural context. These have been a source of conflict between parents and children when caregiving is needed. The parents may expect the children to provide all the care that is needed. The more acculturated children may feel significant conflict as their “American” lives do not reflect or support their filial duties. The concept and use of time is culturally constructed and has significant implications in the use of health care. Time orientation has long been theoretically recognized but often overlooked as a factor influencing the use of health care, especially preventive practices (Lukwago et al., 2001). Older adults are more likely to use the orientation of their culture of origin, which may contrast significantly with that of the health care system in the United States.

Culture, Gender, and Aging

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

The Gerontological Explosion

Health Disparities and Older Adults

Health Disparities

TOPIC

BETTER THAN WHITES

WORSE THAN WHITES

Cancer

Colorectal cancer diagnosed at advanced stage

Adults age 50 and over who report they ever received a colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, proctoscopy, or fecal occult blood test

Colorectal cancer deaths per 100,000 population

Breast cancer diagnosed at advanced stage

Cancer deaths per 100,000 female population due to breast cancer

Heart disease

Deaths per 1000 admissions with acute myocardial infarction as principal diagnosis, age 18 and over

Hospital patients who received recommended care for heart failure

HIV and AIDS

New AIDS cases per 100,000 population age 13 and over

Respiratory diseases

Adults age 65 and over who ever received pneumococcal vaccination

Hospital patients with pneumonia who received recommended care

Functional status preservation and rehabilitation

Female Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and over who reported ever being screened for osteoporosis

Supportive and palliative care

Long-stay nursing home residents who were physically restrained

High-risk long-stay nursing home residents with pressure sores

Short-stay nursing home residents with pressure sores

Home health care patients who were admitted to the hospital

Timeliness

Emergency department visits in which patients left without being seen

Access

People without a usual source of care due to a financial or insurance reason

People who have a usual primary care provider

AI/AN, American Indian or Alaska Native; API, Asian or Pacific Islander. (From Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research: Older adults: prevention, influenza vaccination. In: National healthcare quality report, 2009. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr09/Chap4d.htm#older_adults. Accessed December 2010.)

Cultural Proficiency

Cultural Awareness

Cultural Knowledge

Definitions of Terms

Orientation to Time

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Culture, Gender, and Aging

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access