Linda A. Stamm, APN, BC, Laurel A. Wiersema-Bryant, ANP, BC and Cassandra Ward, ANP-C On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Describe the age-related physiologic and functional changes in the gastrointestinal system. 2. Explain primary and secondary preventive care related to the gastrointestinal tract for older clients and the rationalizations for such care. 3. Discuss the alterations of normal structure and function accompanying common gastrointestinal diseases of older adults. 4. Describe appropriate evaluation of older clients with symptoms related to a gastrointestinal disorder. 5. Describe the cause, incidence, and pathophysiology of the various types of gastrointestinal disorders, including cancer and liver disease. 6. Discuss the nursing management of gastrointestinal disorders in older adults. 7. Write an appropriate care plan for an older client with a gastrointestinal disorder. Changes in the oral cavity have an effect not only on an older person’s well being, comfort, and health, but also on overall nutrition and digestion. The most obvious change in the mouth is the loss of teeth. One fourth of adults who are 65 or older are edentulous (without teeth). More than 7000 people, mainly elderly, die each year from pharyngeal and oral cancers. Periodontal gum disease caused by bacterial infection under the gum destroys both bone and gum. Teeth become loose, chewing becomes more difficult, and often the teeth must be extracted (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009a). Taste buds may atrophy with age, resulting in an inability to discriminate among flavors, especially salty and sweet. This may contribute to decreased enjoyment of food, resulting in poor eating habits and nutritional deficiencies. Medications such as diuretics, anticholinergics, certain antidepressants and antipsychotics reduce saliva production and oral lubrication, which normally function to protect the oral tissues (Lewis, Heitkemper, Dirksen, & O’Brien, 2007). Healthy People 2010 reflects on the importance of oral health as an integral component of healthy life. Poor oral health and disease conditions have a significant impact on the older adult’s feelings of self-esteem and depression. One of the goals of Healthy People 2010 is to improve access to preventive oral care and early intervention services for older adults (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Many of the age-related changes in the esophagus result in a decline in its motility. Degenerative changes in the smooth muscle lining the lower esophagus may contribute to a decrease in the strength of esophageal contractions and sphincter weakness. This condition, referred to as presbyesophagus, causes older adults to be more prone to reflux of acid from the stomach or gastroesophageal reflux (LeMone & Burke, 2008). Neurogenic, hormonal, and vascular changes may also contribute to a decrease in esophageal motility. These changes may lead to complaints of dysphagia, heartburn, or vomiting of undigested foods. Subsequently, poor nutrition, dehydration, and decreased food intake often result. Age-related changes in the stomach include degeneration of the gastric mucosa, decreased secretion of gastric acids and digestive enzymes, and decreased motility (Lewis et al, 2007). The stomach of an older adult is not able to accommodate large amounts of food because of decreased elasticity. The ability to empty gastric contents as quickly is also diminished in the older adult, which quickly results in a feeling of fullness or early satiation. Age-related changes in the small intestine include atrophy of the muscle and mucosal surfaces, thinning of the villi, and a decrease in epithelial cells. This results in some decrease in the absorption of fats and vitamin B12. A number of disorders may cause malabsorption, including infection, small intestine diverticuli (small dilations or pockets leading off the tract), pancreatic insufficiency, celiac disease, and mental disorders such as dementia. Elderly patients with malabsorption are undernourished, weak, and debilitated. Nursing management includes disease-specific treatment and appropriate nutrition (Timiras, 2007). The main function of the large intestine is storage, propulsion, and evacuation of feces. Age-related changes in the large intestine include atrophy of the mucosa, proliferation of connective tissue, and vascular changes, of which most are atherosclerotic. The tone of the internal anal sphincter decreases, which may lead to incontinence or incomplete emptying of the bowel. Nerve impulses that usually indicate the need to defecate may be diminished. This may account for the increased incidence of constipation (Lewis et al, 2007). In addition, the incidence of diverticuli is increased in the elderly. Diverticuli are prevalent in 30% to 40% of people older than 50 years (Timiras, 2007). The gallbladder and bile ducts are unaffected by aging. However, the incidence of gallstones does increase with age. Bile may become more lithogenic with advancing age, possibly because of an increase in biliary cholesterol related to diet and hormonal changes that affect cholesterol metabolism. The bile salt pool also decreases as a result of a decrease in bile salt synthesis. These predispositions for stone development, along with a tendency for dehydration in older adults, explain the increased incidence of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis in older adults. The complications of cholelithiasis in older adults include empyema, perforation, and choledocholithiasis (calculi in the common bile duct). These complications are often seen in persons older than age 65 and those with diabetes (Lewis et al, 2007). The pancreas shows some age-related changes, such as fibrosis, fatty acid deposits, and atrophy, but the size is not affected (Lewis et al, 2007). However, the volume of pancreatic secretions declines after the age of 40, and enzyme output diminishes with advancing age. This decrease in enzyme activity affects the digestion of fats and may account for a vague intolerance of fatty foods in older adults. There is an increased incidence of pancreatic cancer and pancreatitis in older adults. The liver is a sturdy organ and retains most of its functions throughout the life span. Although the liver size decreases after age 50, liver function tests may remain within normal limits. A decline in cardiac output associated with aging contributes to a decrease in hepatic blood flow. As hepatic blood flow slows, drug metabolism is reduced, which leaves the aging liver more susceptible to drugs and toxins. Elderly persons have a decreased ability to compensate for infectious, immunologic, and metabolic disorders (Lewis et al, 2007). Some evidence suggests that normal aging may adversely affect liver tissue regeneration. The mechanism of this effect is not fully known, but it may be a result of a generalized slowing of repair or an inadequate response to regeneration of liver tissue. Although some changes in the GI system are associated with aging, there are strategies for both primary and secondary prevention of problems arising from these changes (Tables 26–1, 26–2 and Box 26–1). Nurses caring for older clients should include instruction regarding these strategies. TABLE 26–1 ∗If colonoscopy is unavailable, not feasible, or not desired by the patient, DCBE alone or the combination of flexible sigmoidoscopy and DCBE are acceptable alternatives. Adding flexible sigmoidoscopy to DCBE may provide a more comprehensive diagnostic evaluation than DCBE alone in finding significant lesions. A supplementary DCBE may be needed if a colonoscopic examination fails to reach the cecum, and a supplementary colonoscopy may be needed if a DCBE identifies a possible lesion or does not adequately visualize the entire colorectum. †There is no justification for repeating FOBT in response to an initial positive finding. Data from Smith R, Cokkinides V, Brawley O: Cancer screening in the United States, 2009: a review of current American Cancer Society Guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 59(1):27–41, 2009. TABLE 26–2 ∗If colonoscopy is unavailable, not feasible, or not desired by the patient, double contrast barium enema (DCBE) alone or the combination of flexible sigmoidoscopy and DCBE are acceptable alternatives. Adding flexible sigmoidoscopy to DCBE may provide a more comprehensive diagnostic evaluation than DCBE alone in finding significant lesions. A supplementary DCBE may be needed if a colonoscopic examination fails to reach the cecum, and a supplementary colonoscopy may be needed if a DCBE identifies a possible lesion or does not adequately visualize the entire colorectum. From Smith R, Cokkinides V, Brawley O: Cancer screening in the United States, 2009: a review of current American Cancer Society Guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 59(1):27–41, 2009. Older adults may complain of symptoms related to the GI tract that have not been related to a specific diagnosis. Any symptom reported by an older client needs to be thoroughly assessed by the nurse. Following are a few of the common GI symptoms experienced by older adults; the sections include information on their definitions, assessment, nursing interventions, and self-care measures. (For more on nursing assessment as it relates to various cultures, see Chapter 4) Vomiting is controlled through a central vomiting center in the medulla. This center is close to the pain and respiratory centers; it is also near the centers that control vestibular and vasomotor function. Occasionally stimuli from one center spill over to another, and symptoms may become mixed. No distinct nausea center exists; however, the symptom of nausea may result from early stimulation of the vomiting center (Fig. 26–1). Anorexia as a symptom should not be confused with anorexia nervosa, which is an eating disorder of psychiatric significance. The term anorexia literally means “lack of appetite.” Hunger and appetite are not synonymous; hunger is related to the physiologic need for food. It is important for the nurse to ascertain whether the decreased food intake is truly because of a loss of appetite. Once that is determined, the nurse must ask questions regarding other symptoms, including weight loss, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation. In addition, psychosocial factors such as stress, grief, pain, and concomitant illnesses may also need to be assessed. Older adults are often faced with limited financial resources. This may result in them purchasing less fresh fruits and vegetables and may limit their overall ability to purchase enough food (Lewis et al, 2007). The symptom of abdominal pain is often difficult to fully assess. With older adults, it can be even more difficult, even for a skilled clinician. The assessment of pain can be made easier by thinking in terms of the three pathways for pain impulses. The first type are the visceral pain pathways, which are activated by receptors in the wall of the abdominal viscera and develop from stretching or distending the abdominal wall or from inflammation. This pain is often diffuse, is poorly localized, and has a gnawing, burning, or cramping quality. The second type are somatic or parietal pathways, which are activated by receptors in the parietal peritoneum and other supporting tissues. This type of pain is usually sharp, more intense, constant, and better localized than visceral pain. The third type are referral pathways, which account for referred pain (i.e., pain felt at a different site than the source of the pain but sharing the same dermatome). This pain is usually sharp and well localized; it may resemble somatic pain (Fig. 26–2). In assessing any type of pain, the nurse should elicit information about its duration, location, mode of onset (sudden or gradual), intensity, quality, rhythm, relationship to food, alleviating and aggravating factors, and radiation (e.g., back, neck, or groin), as well as the older client’s ability to pass stool and gas. Elderly persons may complain of vague symptoms and wait much longer than their younger counterparts to seek medical care. The elderly are also less likely to exhibit leukocytosis (an increased white blood cell count), fevers, rebound tenderness, or local rigidity (Tazkarji, 2008). Constipation is a common problem among the elderly secondary to physiologic changes and is often a complication of polypharmacy. Among those older than 65, women are more often affected than men. Constipation is often defined according to the patient’s perception of abnormal bowel function (Berman, Brooks, & Silver, 2007). However, normal bowel patterns differ greatly among individuals. For example, a client may have the misperception that one bowel movement a day is necessary for good health. Common causes of constipation in the elderly include diet (decreased fiber intake), mechanical obstruction (fecal impaction and cancer), medication side effects (aluminum- and calcium-based antacids, iron preparations, anticholinergics, narcotics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and overuse of laxatives), multiple comorbidities, and mobility and functional issues (Ginsberg, Phillips, Wallace, & Josephson, 2007). Perhaps the most widespread cause of constipation in older adults is diet. It is usually a lack of certain foods, rather than the addition of certain foods, that leads to the problem. For example, many foods, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, contain natural laxatives, although older adults may have difficulty eating these foods because of dental problems. A second dietary cause of constipation is the lack of fiber or bulk and a decrease in fluid intake. In general, unrefined foods have more fiber than the refined foods that are popular in American society. Limitations on mobility can greatly affect the ability of an elderly person to self-feed and physically reach the toilet. They may feel awkward depending on others for these functions. Subsequently, they may ignore the urge to defecate rather than ask for help to get to the toilet. They may also decrease fluid intake in an effort to prevent urinary incontinence. These factors may greatly influence regular bowel patterns (Lewis et al, 2007). Fecal incontinence, the involuntary passing of stool, may be acute or chronic, and it demands evaluation. For older adults the loss of bowel control is devastating and may significantly alter their quality of life. Fecal incontinence may be a result of colorectal lesions (perianal disease, proctitis, and tumors), neurologic problems (dementia, stroke, spinal cord lesions), laxative abuse, unrecognized lactose intolerance, diabetic neuropathy, poor dietary habits, or immobility (Kane, Ouslander, Abrass, & Resnick, 2009). The following is an overview of common GI disorders seen in older clients, including the related nursing care. Table 26–3 provides an explanation of the diagnostic tests used in this section. TABLE 26–3 Before the procedure, administer laxatives and enemas until colon is clear of stool evening before procedure. Administer clear liquid diet evening before procedure. Keep patient NPO for 8 hr before test. Instruct patient about being given barium by enema. Explain that cramping and urge to defecate may occur during procedure and that patient may be placed in various positions on tilt table. After the procedure, give fluids, laxatives, or suppositories to assist in expelling barium. Observe stool for passage of contrast medium. Before the procedure, keep patient NPO for 8 hr. Make sure signed consent is on chart. Give preoperative medication if ordered. Explain to patient that local anesthetic may be sprayed on throat before insertion of scope and that patient will be sedated during the procedure. After the procedure, keep patient NPO until gag reflex returns. Gently tickle back of throat to determine reflex. Use warm saline gargles for relief of sore throat. Check temperature q15–30min for 1–2 hr (sudden temperature spike is sign of perforation). Before the procedure, a bowel preparation is done. Type of preparation varies depending on physician. For example, patients may be kept on clear liquids 1–2 days before procedure. Cathartic and/or enema may be given the night before. An alternative is to give 1 gal of polyethylene glycol (GoLYTELY, Colyte) evening before (8 oz glass q10min). Explain to patient that flexible scope will be inserted while patient is in side-lying position. Explain to patient that sedation will be given. After the procedure, be aware that patient may experience abdominal cramps caused by stimulation of peristalsis because the bowel is constantly inflated with air during procedure. Observe for rectal bleeding and signs of perforation (e.g., malaise, abdominal distention, tenesmus). Check vital signs. Dietary preparation: similar to colonoscopy. The video capsule is swallowed, and the patient is usually kept NPO until 4–6 hr later. Procedure is comfortable for most patients. Eight hours after swallowing the capsule, the patient returns to have the monitoring device removed. Peristalsis causes passage of the disposable capsule with a bowel movement. Before the procedure, explain procedure to patient, including patient role. Keep patient NPO 8 hr before procedure. Ensure that consent form is signed. Administer sedation immediately before and during procedure. Administer antibiotics if ordered. After the procedure, check vital signs. Check for signs of perforation or infection. Be aware that pancreatitis is most common complication. Check for return of gag reflex. NPO, Nothing by mouth; IV, intravenous; NG, nasogastric. From Lewis S, Heitkemper M, Dirksen S, O’Brien B: Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, ed 7, St Louis, 2007, Mosby. Candida albicans, or thrush, is an infection causing white lesions on the oral mucosa. It is often seen in persons with compromised immune systems and in those with suppressed immunity, such as individuals taking immunosuppressant drugs and antibiotics. The condition is most common in denture-bearing tissues of the mouth. The client may complain of an unpleasant taste, burning, or itching or may be asymptotic (Duthie, Katz, & Malone, 2007). Dysphagia (difficult swallowing) is a common problem with increased prevalence in the elderly population. Weakened esophageal smooth muscle and incompetent sphincter function are contributory in the elderly who develop dysphagia. Dysphagia is a symptom with many underlying causes, including stroke, neurologic disease (Alzheimer’s disease), local trauma or tissue damage, and tumors that may obstruct the flow of food and liquids in the esophagus. Symptoms may range from mild to severe to a complete inability to swallow (Lewis et al, 2007). Expected outcomes for an older client with dysphagia include 1. The client will maintain weight within 10% of ideal body weight. 2. The client will remain free from aspiration. 3. The client will learn techniques to swallow that minimize pain. 4. The client will be free of epigastric discomfort. 5. The client will be able to verbalize fears related to the diagnosis and prognosis. Gastroesophageal reflux is a prevalent condition in the elderly, found in 20% to 50% of the geriatric population. Causes are diminished esophageal peristalsis, poor clearance of gastric acid, esophageal injury, and a decrease in salivary secretions. The elderly also take medications that can decrease esophageal sphincter pressures. Examples of medications that may induce esophageal injury include tetracycline, alendronate, potassium chloride, quinidine, aspirin, ascorbic acid, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), clindamycin, and theophylline. The elderly often take medications lying down, pills may be too large causing injury to the esophagus, and inadequate fluids may be taken with medications and worsen symptoms (Wolfe, 2006). A hiatal hernia (diaphragmatic or esophageal hernia) is a major cause of reflux and esophagitis and occurs when part of the stomach protrudes through an opening of the diaphragm (Fig. 26–3). The condition may he intermittent or continuous. The continuous type is least common, accounting for only about 10% of cases. Either part or all of the stomach, and even the intestines, may herniate, causing dyspepsia, severe pain, and often a gastric ulceration. The intermittent type, or sliding hernia, occurs with changes in position or with increased peristalsis. The stomach is forced through the opening of the diaphragm when the person is prone and moves back to its normal position when the person stands up. Most hiatal hernias are asymptomatic and require no treatment. Symptoms, when they arise, include heartburn, gastric regurgitation, dysphagia, and indigestion. These symptoms are accentuated (1) when in the supine position after meals, (2) after overeating, (3) after physical exertion, or (4) with a sudden change in posture (Lewis et al, 2007).

Gastrointestinal Function

Age-Related Changes in Structure and Function

Oral Cavity and Pharynx

Esophagus

Stomach

Small Intestine

Large Intestine

Gallbladder

Pancreas

Liver

Prevention

TEST

INTERVAL (BEGINNING AT AGE 50)

COMMENT

Fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and flexible sigmoidoscopy

FOBT annually and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years

Flexible sigmoidoscopy together with FOBT is preferred compared with FOBT or flexible sigmoidoscopy alone. All positive test results should be followed up with colonoscopy.∗

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

Every 5 years

All positive test results should be followed up with colonoscopy.∗

FOBT

Annually

The recommended take-home multiple sample method should be used. All positive test results should be followed up with colonoscopy.∗†

Colonoscopy

Every 10 years

Colonoscopy provides an opportunity to visualize, sample and/or remove significant lesions.

Double contrast barium enema (DCBE)

Every 5 years

All positive test results should be followed up with colonoscopy.

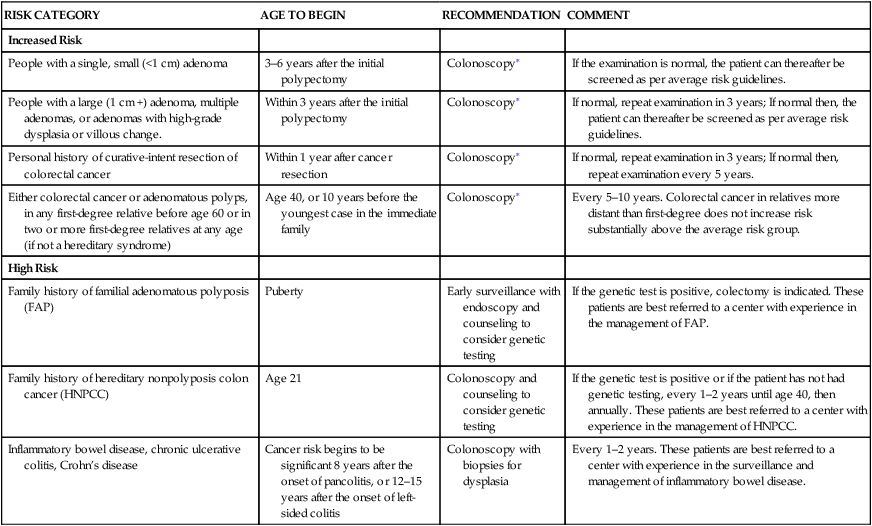

RISK CATEGORY

AGE TO BEGIN

RECOMMENDATION

COMMENT

Increased Risk

People with a single, small (<1 cm) adenoma

3–6 years after the initial polypectomy

Colonoscopy∗

If the examination is normal, the patient can thereafter be screened as per average risk guidelines.

People with a large (1 cm +) adenoma, multiple adenomas, or adenomas with high-grade dysplasia or villous change.

Within 3 years after the initial polypectomy

Colonoscopy∗

If normal, repeat examination in 3 years; If normal then, the patient can thereafter be screened as per average risk guidelines.

Personal history of curative-intent resection of colorectal cancer

Within 1 year after cancer resection

Colonoscopy∗

If normal, repeat examination in 3 years; If normal then, repeat examination every 5 years.

Either colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps, in any first-degree relative before age 60 or in two or more first-degree relatives at any age (if not a hereditary syndrome)

Age 40, or 10 years before the youngest case in the immediate family

Colonoscopy∗

Every 5–10 years. Colorectal cancer in relatives more distant than first-degree does not increase risk substantially above the average risk group.

High Risk

Family history of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

Puberty

Early surveillance with endoscopy and counseling to consider genetic testing

If the genetic test is positive, colectomy is indicated. These patients are best referred to a center with experience in the management of FAP.

Family history of hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC)

Age 21

Colonoscopy and counseling to consider genetic testing

If the genetic test is positive or if the patient has not had genetic testing, every 1–2 years until age 40, then annually. These patients are best referred to a center with experience in the management of HNPCC.

Inflammatory bowel disease, chronic ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease

Cancer risk begins to be significant 8 years after the onset of pancolitis, or 12–15 years after the onset of left-sided colitis

Colonoscopy with biopsies for dysplasia

Every 1–2 years. These patients are best referred to a center with experience in the surveillance and management of inflammatory bowel disease.

Common Gastrointestinal Symptoms

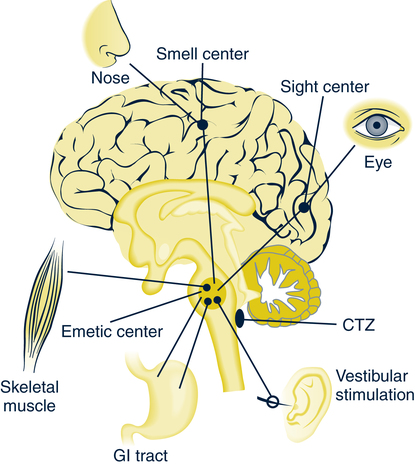

Nausea and Vomiting

Anorexia

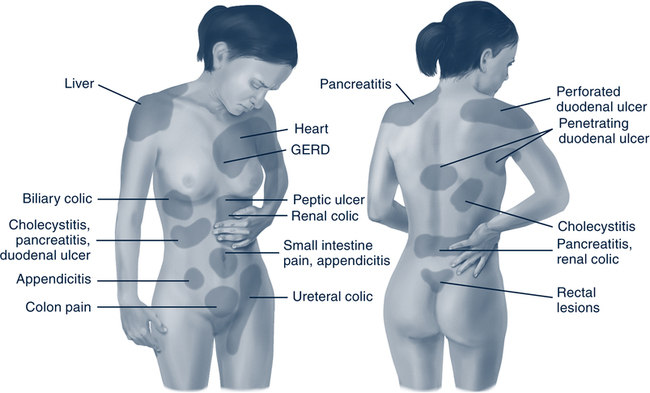

Abdominal Pain

Constipation

Fecal Incontinence

Common Diseases of the Gastrointestinal Tract

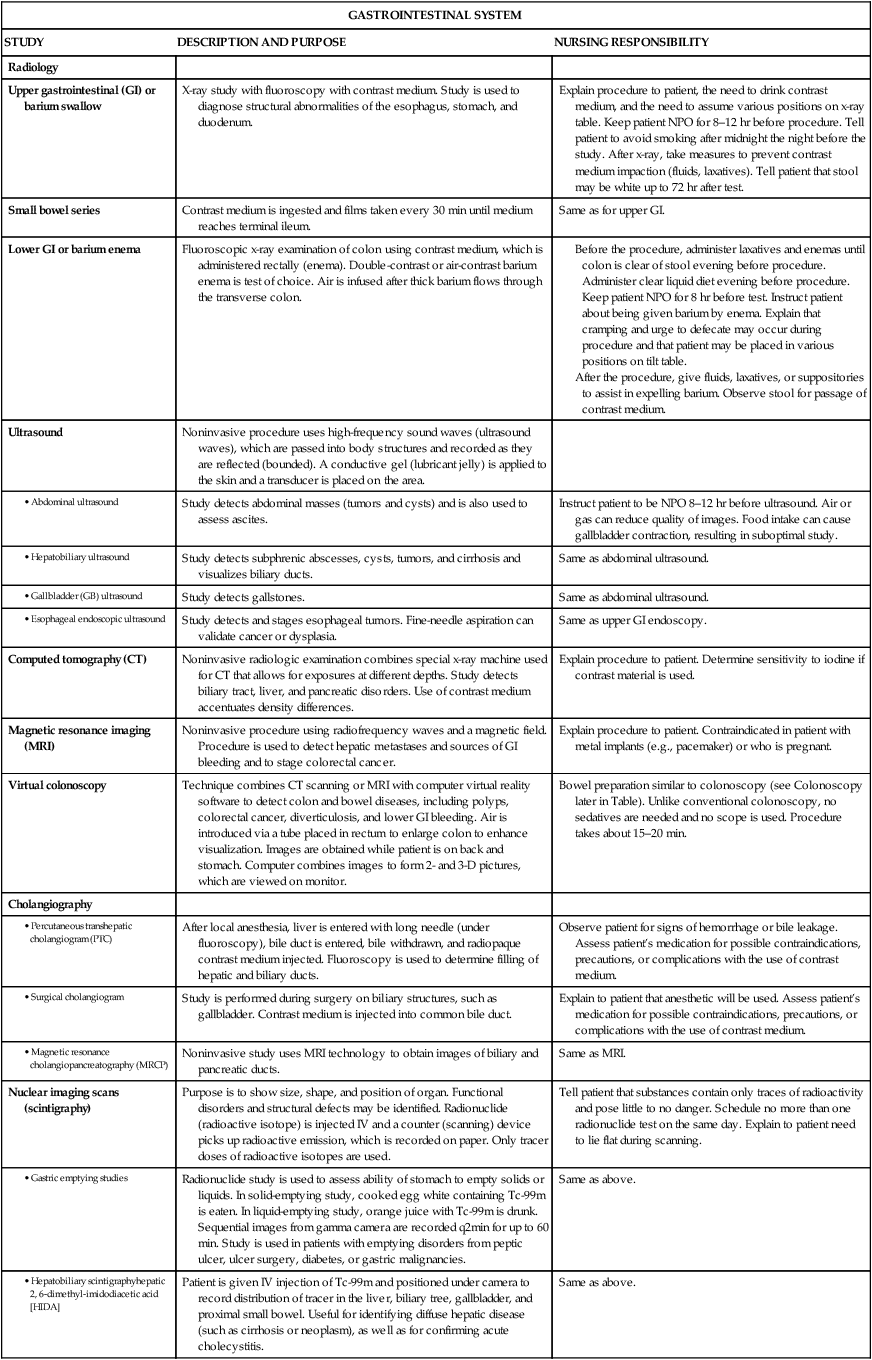

GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

STUDY

DESCRIPTION AND PURPOSE

NURSING RESPONSIBILITY

Radiology

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) or barium swallow

X-ray study with fluoroscopy with contrast medium. Study is used to diagnose structural abnormalities of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum.

Explain procedure to patient, the need to drink contrast medium, and the need to assume various positions on x-ray table. Keep patient NPO for 8–12 hr before procedure. Tell patient to avoid smoking after midnight the night before the study. After x-ray, take measures to prevent contrast medium impaction (fluids, laxatives). Tell patient that stool may be white up to 72 hr after test.

Small bowel series

Contrast medium is ingested and films taken every 30 min until medium reaches terminal ileum.

Same as for upper GI.

Lower GI or barium enema

Fluoroscopic x-ray examination of colon using contrast medium, which is administered rectally (enema). Double-contrast or air-contrast barium enema is test of choice. Air is infused after thick barium flows through the transverse colon.

Ultrasound

Noninvasive procedure uses high-frequency sound waves (ultrasound waves), which are passed into body structures and recorded as they are reflected (bounded). A conductive gel (lubricant jelly) is applied to the skin and a transducer is placed on the area.

Study detects abdominal masses (tumors and cysts) and is also used to assess ascites.

Instruct patient to be NPO 8–12 hr before ultrasound. Air or gas can reduce quality of images. Food intake can cause gallbladder contraction, resulting in suboptimal study.

Study detects subphrenic abscesses, cysts, tumors, and cirrhosis and visualizes biliary ducts.

Same as abdominal ultrasound.

Study detects gallstones.

Same as abdominal ultrasound.

Study detects and stages esophageal tumors. Fine-needle aspiration can validate cancer or dysplasia.

Same as upper GI endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT)

Noninvasive radiologic examination combines special x-ray machine used for CT that allows for exposures at different depths. Study detects biliary tract, liver, and pancreatic disorders. Use of contrast medium accentuates density differences.

Explain procedure to patient. Determine sensitivity to iodine if contrast material is used.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Noninvasive procedure using radiofrequency waves and a magnetic field. Procedure is used to detect hepatic metastases and sources of GI bleeding and to stage colorectal cancer.

Explain procedure to patient. Contraindicated in patient with metal implants (e.g., pacemaker) or who is pregnant.

Virtual colonoscopy

Technique combines CT scanning or MRI with computer virtual reality software to detect colon and bowel diseases, including polyps, colorectal cancer, diverticulosis, and lower GI bleeding. Air is introduced via a tube placed in rectum to enlarge colon to enhance visualization. Images are obtained while patient is on back and stomach. Computer combines images to form 2- and 3-D pictures, which are viewed on monitor.

Bowel preparation similar to colonoscopy (see Colonoscopy later in Table). Unlike conventional colonoscopy, no sedatives are needed and no scope is used. Procedure takes about 15–20 min.

Cholangiography

After local anesthesia, liver is entered with long needle (under fluoroscopy), bile duct is entered, bile withdrawn, and radiopaque contrast medium injected. Fluoroscopy is used to determine filling of hepatic and biliary ducts.

Observe patient for signs of hemorrhage or bile leakage. Assess patient’s medication for possible contraindications, precautions, or complications with the use of contrast medium.

Study is performed during surgery on biliary structures, such as gallbladder. Contrast medium is injected into common bile duct.

Explain to patient that anesthetic will be used. Assess patient’s medication for possible contraindications, precautions, or complications with the use of contrast medium.

Noninvasive study uses MRI technology to obtain images of biliary and pancreatic ducts.

Same as MRI.

Nuclear imaging scans (scintigraphy)

Purpose is to show size, shape, and position of organ. Functional disorders and structural defects may be identified. Radionuclide (radioactive isotope) is injected IV and a counter (scanning) device picks up radioactive emission, which is recorded on paper. Only tracer doses of radioactive isotopes are used.

Tell patient that substances contain only traces of radioactivity and pose little to no danger. Schedule no more than one radionuclide test on the same day. Explain to patient need to lie flat during scanning.

Radionuclide study is used to assess ability of stomach to empty solids or liquids. In solid-emptying study, cooked egg white containing Tc-99m is eaten. In liquid-emptying study, orange juice with Tc-99m is drunk. Sequential images from gamma camera are recorded q2min for up to 60 min. Study is used in patients with emptying disorders from peptic ulcer, ulcer surgery, diabetes, or gastric malignancies.

Same as above.

Patient is given IV injection of Tc-99m and positioned under camera to record distribution of tracer in the liver, biliary tree, gallbladder, and proximal small bowel. Useful for identifying diffuse hepatic disease (such as cirrhosis or neoplasm), as well as for confirming acute cholecystitis.

Same as above.

Tc-99m–labeled sulfur colloid or Tc-99m labeling of the patient’s own red blood cells (RBCs) can accurately determine the site of active GI blood loss. The sulfur colloid or the patient’s RBCs are injected, and images of the abdomen are obtained intermittently.

Same as above.

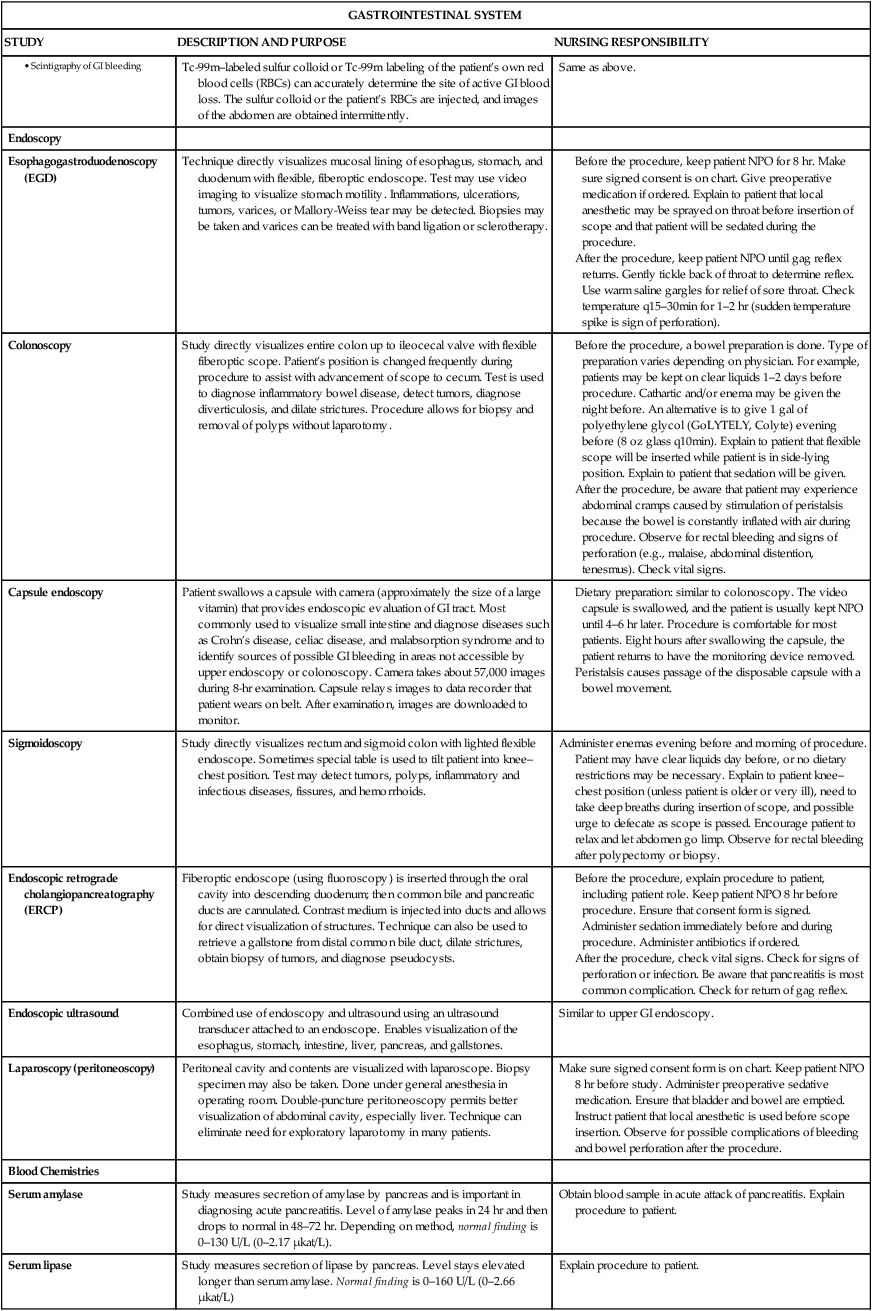

Endoscopy

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

Technique directly visualizes mucosal lining of esophagus, stomach, and duodenum with flexible, fiberoptic endoscope. Test may use video imaging to visualize stomach motility. Inflammations, ulcerations, tumors, varices, or Mallory-Weiss tear may be detected. Biopsies may be taken and varices can be treated with band ligation or sclerotherapy.

Colonoscopy

Study directly visualizes entire colon up to ileocecal valve with flexible fiberoptic scope. Patient’s position is changed frequently during procedure to assist with advancement of scope to cecum. Test is used to diagnose inflammatory bowel disease, detect tumors, diagnose diverticulosis, and dilate strictures. Procedure allows for biopsy and removal of polyps without laparotomy.

Capsule endoscopy

Patient swallows a capsule with camera (approximately the size of a large vitamin) that provides endoscopic evaluation of GI tract. Most commonly used to visualize small intestine and diagnose diseases such as Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and malabsorption syndrome and to identify sources of possible GI bleeding in areas not accessible by upper endoscopy or colonoscopy. Camera takes about 57,000 images during 8-hr examination. Capsule relays images to data recorder that patient wears on belt. After examination, images are downloaded to monitor.

Sigmoidoscopy

Study directly visualizes rectum and sigmoid colon with lighted flexible endoscope. Sometimes special table is used to tilt patient into knee–chest position. Test may detect tumors, polyps, inflammatory and infectious diseases, fissures, and hemorrhoids.

Administer enemas evening before and morning of procedure. Patient may have clear liquids day before, or no dietary restrictions may be necessary. Explain to patient knee–chest position (unless patient is older or very ill), need to take deep breaths during insertion of scope, and possible urge to defecate as scope is passed. Encourage patient to relax and let abdomen go limp. Observe for rectal bleeding after polypectomy or biopsy.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Fiberoptic endoscope (using fluoroscopy) is inserted through the oral cavity into descending duodenum; then common bile and pancreatic ducts are cannulated. Contrast medium is injected into ducts and allows for direct visualization of structures. Technique can also be used to retrieve a gallstone from distal common bile duct, dilate strictures, obtain biopsy of tumors, and diagnose pseudocysts.

Endoscopic ultrasound

Combined use of endoscopy and ultrasound using an ultrasound transducer attached to an endoscope. Enables visualization of the esophagus, stomach, intestine, liver, pancreas, and gallstones.

Similar to upper GI endoscopy.

Laparoscopy (peritoneoscopy)

Peritoneal cavity and contents are visualized with laparoscope. Biopsy specimen may also be taken. Done under general anesthesia in operating room. Double-puncture peritoneoscopy permits better visualization of abdominal cavity, especially liver. Technique can eliminate need for exploratory laparotomy in many patients.

Make sure signed consent form is on chart. Keep patient NPO 8 hr before study. Administer preoperative sedative medication. Ensure that bladder and bowel are emptied. Instruct patient that local anesthetic is used before scope insertion. Observe for possible complications of bleeding and bowel perforation after the procedure.

Blood Chemistries

Serum amylase

Study measures secretion of amylase by pancreas and is important in diagnosing acute pancreatitis. Level of amylase peaks in 24 hr and then drops to normal in 48–72 hr. Depending on method, normal finding is 0–130 U/L (0–2.17 μkat/L).

Obtain blood sample in acute attack of pancreatitis. Explain procedure to patient.

Serum lipase

Study measures secretion of lipase by pancreas. Level stays elevated longer than serum amylase. Normal finding is 0–160 U/L (0–2.66 μkat/L)

Explain procedure to patient.

Liver biopsy

Percutaneous procedure uses needle inserted between sixth and seventh or eighth and ninth intercostal spaces on the right side to obtain specimen of hepatic tissue. Often done using ultrasound or CT guidance.

Before the procedure, check patient’s coagulation status (prothrombin time, clotting or bleeding time). Ensure that patient’s blood is typed and cross-matched. Take vital signs as baseline data. Explain holding of breath after expiration when needle is inserted. Ensure that informed consent has been signed.

After the procedure, check vital signs to detect internal bleeding q15min × 2, q30min × 4, q1hr × 4. Keep patient lying on right side for minimum of 2 hr to splint puncture site. Keep patient in bed in flat position for 12–14 hr. Assess patient for complications such as bile peritonitis, shock, and pneumothorax.

Miscellaneous Tests

Gastric analysis

Purpose is to analyze gastric contents for acidity and volume. NG tube is inserted, and gastric contents are aspirated. Contents are analyzed mainly for HCl acid, but pH, pepsin, and electrolytes may be determined. Histalog and pentagastrin may be used to stimulate HCl acid secretion. Exfoliative cytology may be done to determine whether malignant cells are present. With fasting, normal acidity is 2.5 mEq/L (2.5 mmol/L) and normal volume is 62 mL/hr; 30 min after Histalog or pentagastrin administration, normal acidity is 1.5 mEq/L (1.5 mmol/L) and normal volume is 110 mL/hr.

Keep patient NPO for 8–12 hr. Explain insertion of NG tube. Withhold drugs affecting gastric secretions 24–48 hr before test. Ensure no smoking morning of test (nicotine increases gastric secretion).

Fecal analysis

Form, consistency, and color are noted. Specimen examined for mucus, blood, pus, parasites, and fat content. Tests for occult blood (guaiac test, Hemoccult, Hematest) are done.

Observe patient’s stools. Collect stool specimens. Check stools for blood with Hemoccult or Hematest. Keep diet free of red meat for 24–48 hr before guaiac test.

Stool culture

Tests for the presence of bacteria, including Clostridium difficile.

Collect stool specimen.

Gingivitis and Periodontitis

Nursing Management

![]() Assessment

Assessment

Dysphagia

Nursing Management

![]() Assessment

Assessment

![]() Planning and Expected Outcomes

Planning and Expected Outcomes

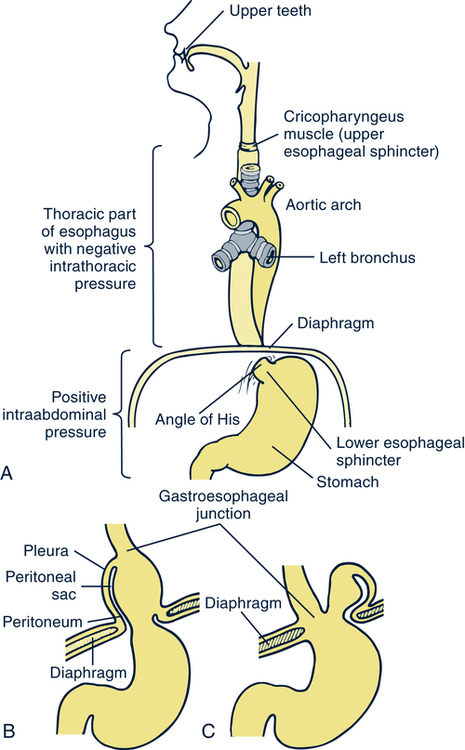

Gastroesophageal Reflux and Esophagitis

Hiatal Hernia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastrointestinal Function

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access