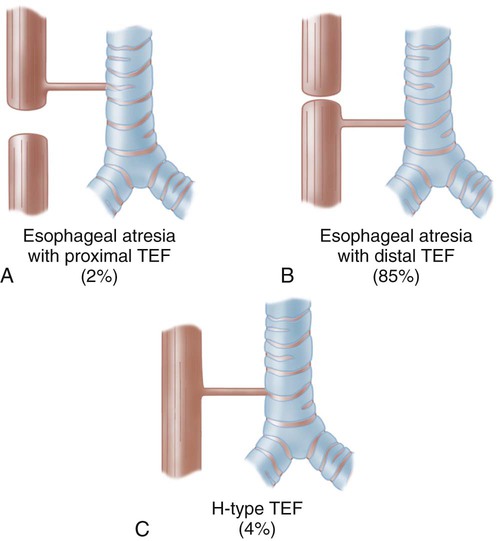

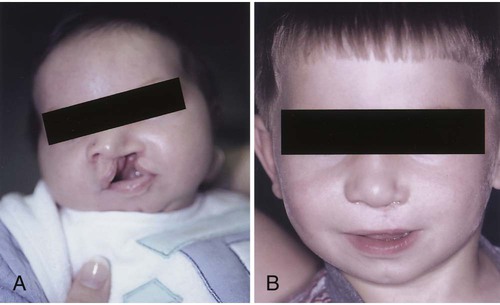

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Describe the changes from infancy with the gastrointestinal system 3. Describe the nursing care of a child with infectious diarrhea 4. Discuss two feeding techniques used for the infant with a cleft lip or cleft palate 5. Summarize the needs of a neonate with tracheoesophageal fistula 6. Identify the nursing care for an infant with biliary atresia 7. Describe the home care of an infant with GER 8. Discuss the different nursing care involved in caring for a child with gastroschisis or omphalocele 9. Discuss the nursing care of a child with celiac disease 10. Identify the difference in symptoms for intussuception and Hirschsprung disorders 11. List the symptoms of appendicitis, and discuss necessary modifications in treatment and postoperative nursing care for a school-age child with a ruptured appendix The gastrointestinal system is completely developed at birth but is not fully mature until after the second year of life. The infant’s sucking and swallowing are automatic reflexes until about 6 weeks of age when nerve and voluntary muscle control has developed. The stomach capacity of the child increases as the child grows (Table 14-1). Table 14-1 Modified from James, S., and Ashwill, J. (2007). Nursing care of children: principles & practice. (3rd ed.). St. Louis: Saunders. Several digestive enzymes are deficient until about 4 to 6 months of age. Amylase (digests carbohydrates), lipase (fat absorption), and lactase (carbohydrate digestion) are insufficient to aid with digestion. Infants who are given solid foods such as cereal before 4 to 6 months of age may develop gas and diarrhea. Introduction of solid foods should not be started until 6 months of age due to the infant’s inability to digest them. It also exposes them to food allergens that may cause food allergies. Despite this recommendation, many parents begin the introduction as early as 2 weeks of age to help the infant sleep better at night or gain weight (Morin, 2004). Iron-fortified infant cereal is usually the first. Rice is suggested as it has low allergy potential. It can be mixed with both breast milk and commercial formula. Fruits and vegetables are next, with meats and eggs by 1 year of age. Either fruits or vegetables can be given first. Whichever, it is highly recommended that only one new food is introduced in a limited amount every 5 to 7 days while monitoring for any reactions. While commercial baby food is very popular, making baby food at home is easy and inexpensive. Steamed fruits and vegetables without seeds can be pureed with water from cooking. Placing small amounts of pureed food in ice cube trays for freezing and storing in freezer bags offers an economical alternative. The initial treatment is surgical repair. The cleft lip is usually repaired first because it interferes with the infant’s ability to eat. If the infant cannot create a vacuum in the mouth, there can be difficulty with sucking. Surgery not only improves the infant’s sucking, it also greatly improves the appearance. Currently, it is performed any time after birth if the infant’s general health is good and there is no infection. Most infants undergo repair at around 10 to 12 weeks of age (Figure 14-1). Breastfeeding is possible for these babies but may require the assistance of a lactation specialist. Infants with cleft lip are usually more successful with breastfeeding than the infant with cleft palate or a cleft lip and cleft palate. Mothers who wish to breastfeed to gain all the benefits from breastfeeding should be supported. Skill 14-1 describes mechanical feeding methods that may be used for infants with both cleft lip and cleft palate. After the infant has established a feeding routine, the infant should be able to complete the feeding in 18 to 30 minutes. An infant who requires a longer feeding period could be working too hard and expending too many calories. This would not promote growth, which is a goal for these infants. It is important for the nurse and the caregiver to remain flexible and patient in feeding these infants. It may require trying several different systems and techniques before the best one is found (Figure 14-2). Most surgeons prefer to operate between 7 to 15 months of age, so that speech patterns are not affected. Even with the advances in surgical techniques, many centers are electing to repair the cleft palate during these times (Campbell et al., 2010). There are several approaches to repair depending on the severity of the defect. While a single surgery may be all that is necessary, future surgical interventions may be required as the child grows. Fluids are best taken by a cup, although an Asepto syringe with a rubber tip (gravity feeder) may be used (Figure 14-3). Hot foods and liquids should be avoided to prevent injury to the surgical site. All objects should be kept out of the mouth. This includes straws, tongue blades, spoons, forks, and pacifiers. A wide-bodied spoon may be used if the food is fed from the side of the spoon and does not come in contact with the roof of the mouth. The diet progresses from a clear to a full liquid diet. The older child may go home on a soft diet (nothing harder than mashed potatoes). Otitis media and dental problems may accompany this condition. The parent should seek medical attention at the first signs of earache. Children with cleft palate are at high risk for developing hearing loss and should be closely followed (Kaster et al., 2008). Because of the involvement of the palate, development of teeth may be involved and the orthodontist may be involved until adulthood. These two defects allow abdominal contents to herniate outside the abdominal cavity (Figure 14-4). The gastroschisis usually occurs to the right of the umbilical cord. It is usually a small defect and involves only the bowel. It does not have a sac covering the defect. An omphalocele is a herniation of the gut into the umbilical cord. It is generally a large defect involving the bowel, liver, spleen, bladder, uterus, or ovaries. It is contained in a translucent sac with amniotic fluid. Improvement with survival rates has been helped by prenatal detection and cesarean delivery in a medical facility able to handle the care of this infant. During the reduction period, the infant is at risk for infection, hypothermia, dehydration and shock, and decreased lower extremity circulation. When the bowel is completely reduced into the abdominal cavity, the infant is ready for complete closure. Postoperative nursing care requires pain control. Nursing priorities include monitoring respiratory and circulatory status and bowel function. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) provides nutritional needs until bowel function has returned. Feeding is introduced slowly as tolerance is monitored. With the improvement of parenteral nutrition and neonatal care, survival rates are 90% to 95% (Durken and Shaaban, 2009). Esophageal atresia (EA) is a congenital defect in which the esophagus fails to connect to the stomach. It ends in a blind pouch. Most cases are associated with tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), which is characterized by an abnormal connection or fistula between the esophagus and the trachea (Figure 14-5). There may be a maternal history of polyhydramnios (excess of amniotic fluid in pregnancy). Early diagnosis is critical to the course of the disorder. A palliative surgery (hepatoportoenterostomy or Kasai procedure) has the best results when done within 60 days of birth. Untreated biliary atresia has a poor prognosis, with death within 2 years (Feldman, 2006). Most of these children will require a liver transplant. The success rate for transplantation has improved. The availability of small donor livers remains an issue. Advances using partial liver transplantation are promising.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Gastrointestinal System

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Newborn

10-20 mL

1 week

30-90 mL

2-3 weeks

75-100 mL

1 month

90-150 mL

3 months

150-200 mL

1 year

210-360 mL

2 years

500 mL

Cleft Lip

Treatment and Nursing Care

Feeding Method for Neonates with Cleft Lip, Cleft Palate, or Both.

Cleft Palate

Treatment

Postoperative Management and Nursing Care

Nutrition.

Complications.

Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

Treatment and Nursing Care

Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophageal Fistula Atresia

Biliary Atresia

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Soft, thin-walled nipple (preemie nipple)

Soft, thin-walled nipple (preemie nipple) NUK orthodontic nipple

NUK orthodontic nipple Cross-cut nipple

Cross-cut nipple Ross Cleft Palate Nurser

Ross Cleft Palate Nurser Mead Johnson Cleft Palate Nurser

Mead Johnson Cleft Palate Nurser Haberman Feeder

Haberman Feeder Pigeon Cleft Palate Nurser

Pigeon Cleft Palate Nurser Asepto syringe, rubber tip

Asepto syringe, rubber tip