Chapter 15 Legal frameworks for the care of the child

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

Note: Please see the website for a list of all the Acts/Statutes referred to in this chapter.

Introduction

Safeguarding children and promoting their welfare is the responsibility of every health and social care professional. An increasing emphasis is placed on outcomes, to be delivered through multi-agency working and information-sharing. Repeatedly, government documents continue to highlight the requirement for interagency and interprofessional working to safeguard and promote the wellbeing of children and young people (DCSF 2010, DH 2000a, Laming 2009). Decisions about children’s welfare and safety are complex, with high-profile deaths of children, such as Victoria Climbié and Baby P, raising criticisms and anxieties about professional decision-making, leadership and management (DH 2003a, Joint Area Review 2008). Whilst the quality of children’s services may be improving, criticisms remain of partnership arrangements, performance management, the involvement of young people in decision-making, the use of assessment to identify need and track progress, and communication to ensure the emergence of a comprehensive picture of a child’s needs (Ofsted 2009, Statham & Aldgate 2003). There are also concerns about high thresholds limiting access to services (Corby 2003, Morris 2005) and lack of compliance by local authorities with the legal rules (Preston-Shoot 2010).

This chapter seeks to enable midwives to understand the legislative framework and related policies, procedures and resources, to carry out their role effectively in working together with parents and other professionals to ensure the wellbeing and safety of children. For the definition of the child, please see Box 15.1. Please note that those working outside England and Wales need to access legislation and policy guidelines relevant to that country.

The Children Act 1989

The Children Act 1989, amplified by associated regulations and statutory guidance, covers legislation relating to aspects of care, upbringing and protection of children (Braye & Preston-Shoot 2009). This includes the welfare and protection of children in disputed divorce proceedings, children in need, children at risk, children with disabilities or special educational needs, and those who need to live away from home (either short or long term) including children in hospital, boarding schools, residential homes and foster homes. These rules have been amended and supplemented by subsequent legislation, most notably the Family Law Act 1996 (to protect victims of domestic violence), the Children (Leaving Care) Act 2000 (duties regarding young people leaving care), the Adoption and Children Act 2002 (reform of adoption law and changes to the Children Act 1989 provisions, for instance concerning parental responsibility, special guardianship and advocacy), the Children Act 2004 (specifying outcomes for children and requirements for interagency working), the Children and Adoption Act 2006 (sanctions for disrupting contact between children and non-resident parents, and changes to family assistance orders), the Children and Young Persons Act 2008 (amendments to children in need and emergency protection order provisions, and changes concerning accommodated children) and the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009 (creating statutory Children’s Trusts and changes to Local Safeguarding Children Boards).

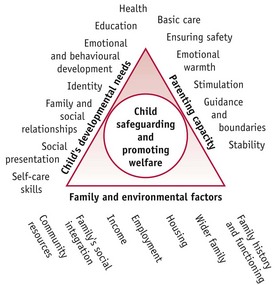

Guidance and regulations produced by central government departments provide detailed information about how legislation should be implemented. When guidance is issued under section 7, Local Authority Social Services Act 1970, it should be followed. Two published examples of these are Working together to safeguard children (DCSF 2010) and Framework for the assessment of children in need and their families (DH 2000a). These provide blueprints for agencies to work together with children (Fig. 15.1). Guidance has also been issued to clarify how outcomes for children, detailed in the Children Act 2004, should be approached (CWDC 2007, DfES 2005).

The midwife has a universal and accepted role in working with pregnant mothers, newborn babies and their parents, and is in a unique position to comment on all aspects of the health and care of newborn babies (see case scenarios and reflective activities on website). This is in direct contrast to some other professionals, for example, social workers and police, who tend to be involved with families when there is cause for concern. Whilst midwives have been involved with all children born in England (approximately 11 million), intervention by councils with social services responsibilities affects only a small proportion of families, estimated to be about 5% (DH 2007). See website and Reflective activity Web 15.2.

Key features of the Children Act 1989

The Act is clear. The paramount duty for everyone is to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. Whilst other objectives, such as working in partnership with parents, are also highlighted, it is important to recognize that these practice principles do not overturn the paramount duty of the local authority to safeguard and promote the welfare of children (Braye & Preston-Shoot 2009, Brayne & Carr 2010, Wilson & James 2007).

Content and structure of the Children Act

Part 1 (section 1): Welfare of the child

Support for children and families

The changing nature of family

Poverty and social exclusion

Sources of stress and disadvantage for children and families include poverty and accompanying social exclusion. The Government published Ending child poverty: everybody’s business (HM Treasury 2008a), its strategy to tackle childhood poverty. In 2009, 2 million children were living in households where there was no adult in paid work, with the impact of poverty on their families being recognized as having a major effect on life chances, health, education and future employment (Hirsch 2009, Platt 2009), especially amongst black and minority ethnic group communities (Butt & Box 1998).

Family support and the Children Act

Local authorities have a general duty to:

The definition of a child in need has been extended to include being a victim of, or witness to, domestic violence (Adoption and Children Act 2002, DH 2000b). The requirement that financial support could be given only in exceptional circumstances has been removed by the Children and Young Persons Act 2008. The aim of the duty to children in need within the Children Act is to target services to the most vulnerable, including those at risk, providing support to avoid the need for the state to seek statutory control. Service provision under section 17 may be one means by which a local authority seeks to deliver good outcomes for children and young people as defined in the Children Act 2004. However, financial constraints, reflected in high thresholds and eligibility criteria, have limited this section’s effectiveness (Morris 2005).