Foundations of Maternity, Women’s Health, and Child Health Nursing

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe the historical background of maternity and child health care.

• Compare current settings for childbirth both within and outside the hospital setting.

• Identify trends that led to the development of family-centered maternity and pediatric care.

• Discuss trends in maternal, infant, and childhood mortality rates.

• Identify how poverty and violence on children and families affect nursing practice.

• Apply theories and principles of ethics to ethical dilemmas.

• Describe the legal basis for nursing practice.

• Identify measures used to defend malpractice claims.

• Identify current trends in health care and their implications for nursing.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

To better understand contemporary maternity nursing and nursing of children, the nurse needs to understand the history of these fields, trends and issues affecting contemporary practice, and the ethical and legal frameworks within which maternity and nursing care of children is provided.

Historical Perspectives

During the past several hundred years, both maternity nursing and nursing of children changed dramatically in response to internal and external environmental factors. Expanding knowledge about the care of women, children, and families, as well as changes in the health care system markedly influenced these developments.

Maternity Nursing

Major changes in maternity care occurred in the first half of the twentieth century as childbirth moved out of the home and into a hospital setting. Rapid change continues as health care reform attempts to control the rising cost of care while advances in expensive technology accelerate. Despite changes, health care professionals attempt to maintain the quality of care.

“Granny” Midwives

Before the twentieth century, childbirth usually occurred in the home with the assistance of a “granny” or lay midwife whose training came through an apprenticeship with a more experienced midwife. Physicians were involved in childbirth only for serious problems.

Although many women and infants fared well when a lay midwife assisted with birth in the home, maternal and infant death rates resulting from childbearing were high. The primary causes of maternal death were postpartum hemorrhage, postpartum infection, also known as puerperal sepsis (or “childbed fever”), and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. The primary causes of infant death were prematurity, dehydration from diarrhea, and contagious diseases.

Emergence of Medical Management

In the late nineteenth century, technologic developments that were available to physicians, but not to midwives, led to a decline in home births and an increase in physician-assisted hospital births. Important discoveries that set the stage for a change in maternity care included:

• The discovery by Semmelweis that puerperal infection could be prevented by hygienic practices

• The development of forceps to facilitate birth

• The discovery of chloroform to control pain during childbirth

• The use of drugs to initiate labor or to increase uterine contractions

By 1960, 90% of all births in the United States occurred in hospitals. Maternity care became highly regimented. All antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum care was managed by physicians. Lay midwifery became illegal in many areas, and nurse-midwifery was not well established. The woman had a passive role in birth, as the physician “delivered” her baby. Nurses’ primary functions were to assist the physician and to follow prescribed medical orders after childbirth. Teaching and counseling by the nurse were not valued at that time.

Unlike home births, early hospital births hindered bonding between parents and infant. During labor, the woman often received medication, such as “twilight sleep,” a combination of a narcotic and scopolamine, that provided pain relief but left the mother disoriented, confused, and heavily sedated. A birth became a delivery performed by a physician. Much of the importance of early contact between parents and child was lost as physician-attended hospital births became the norm. Mothers did not see their newborn for several hours after birth. Formula feeding was the expected method. The father was relegated to a waiting area and was not allowed to see the mother until some time after birth and could only see his child through a window.

Despite the technologic advances and the move from home birth to hospital birth, maternal and infant mortality declined, but slowly. The slow decline was caused primarily by problems that could have been prevented, such as poor nutrition, infectious diseases, and inadequate prenatal care. These stubborn problems remained because of inequalities in health care delivery. Affluent families could afford comprehensive medical care that began early in the pregnancy, but poor families had very limited access to care or to information about childbearing. Two concurrent trends—federal involvement and consumer demands—led to additional changes in maternity care.

Government Involvement in Maternal-Infant Care

The high rates of maternal and infant mortality among indigent women provided the impetus for federal involvement in maternity care. The Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921 provided funds for state-managed programs for mothers and children. Although this act was ruled unconstitutional in 1922, it set the stage for allocation of federal funds. Today the federal government supports several programs to improve the health of mothers, infants, and young children (Table 1-1). Although projects supported by government funds partially solved the problem of maternal and infant mortality, the distribution of health care remained unequal. Most physicians practiced in urban or suburban areas where the affluent could afford to pay for medical services, but women in rural or inner-city areas had difficulty obtaining care. The distribution of health care services is a problem that persists today.

TABLE 1-1

FEDERAL PROJECTS FOR Maternal–Child CARE

| PROGRAM | PURPOSE |

| Title V of Social Security Act | Provides funds for maternal and child health programs |

| National Institute of Health and Human Development | Supports research and education of personnel needed for maternal and child health programs |

| Title V Amendment of Public Health Service Act | Established the Maternal and Infant Care (MIC) project to provide comprehensive prenatal and infant care in public clinics |

| Title XIX of Medicaid program | Provides funds to facilitate access to care by pregnant women and young children |

| Head Start program | Provides educational opportunities for low-income children of preschool age |

| National Center for Family Planning | A clearinghouse for contraceptive information |

| Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program | Provides supplemental food and nutrition information |

| Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) | Provides temporary money for basic living costs of poor children and their families, with eligibility requirements and time limits varying among states; tribal programs available for Native Americans |

| Replaces Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) | |

| Healthy Start program | Enhances community development of culturally appropriate strategies designed to decrease infant mortality and causes of low birth weights |

| Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (PL 94-142) | Provides for free and appropriate education of all disabled children |

| National School Lunch/Breakfast program | Provides nutritionally appropriate free or reduced-price meals to students from low-income families |

The ongoing problem of providing health care for poor women and children left the door open for nurses to expand their roles, and programs emerged to prepare nurses for advanced practice (see Chapter 2).

Impact of Consumer Demands on Health Care

In the early 1950s, consumers began to insist on their right to be involved in their health care. Pregnant women wanted a greater voice in their health care. They wanted information about planning and spacing their children, and they wanted to know what to expect during pregnancy. The father, siblings, and grandparents wanted to be part of the extraordinary events of pregnancy and childbirth. Parents began to insist on active participation in decisions about how their child would be born. Active participation of the patient is now expected in health care at all ages other than the very young or others who are unable to understand.

A growing consensus among child psychologists and nurse researchers indicated that the benefits of early, extended parent-newborn contact far outweighed the risk of infection. Parents began to insist that their infant remain with them, and the practice of separating the well infant from the family was abandoned.

Development of Family-Centered Maternity Care

Family-centered care describes safe, quality care that recognizes and adapts to both the physical and psychosocial needs of the family, including those of the newborn and older children (see also p. 5 for discussion of family-centered child care). The emphasis is on fostering family unity while maintaining physical safety.

Basic principles of family-centered maternity care are as follows:

• Childbirth is usually a normal, healthy event in the life of a family.

• Childbirth affects the entire family, and restructuring of family relationships is required.

Family-centered care increases the responsibilities of nurses. In addition to physical care and assisting the physician, nurses assume a major role in teaching, counseling, and supporting families in their decisions.

Current Settings for Childbirth

As family-centered maternity care has emerged, settings for childbirth have changed to meet the needs of new families.

Traditional Hospital Setting

In hospitals of the past, labor often took place in a functional hospital room, often occupied by several laboring women. When birth was imminent the mother was moved to a delivery area similar to an operating room. After giving birth the mother was transferred to a recovery area for 1 to 2 hours of observation and then taken to a standard hospital room on the postpartum unit. The infant was moved to the newborn nursery when the mother was transferred to the recovery area. Mother and infant were reunited when the mother was settled in her postpartum room. Beginning in the 1970s, the father or another significant support person could usually remain with the mother throughout labor, birth, and recovery, including cesarean birth.

Although birth in a traditional hospital setting was safe, the setting was impersonal and uncomfortable. Moving from room to room, especially during late labor, was a major disadvantage. Each move was uncomfortable for the mother, disrupted the family’s time together, and often separated the parents from the infant. Because of these disadvantages, hospitals began to devise settings that were more comfortable and included family participation.

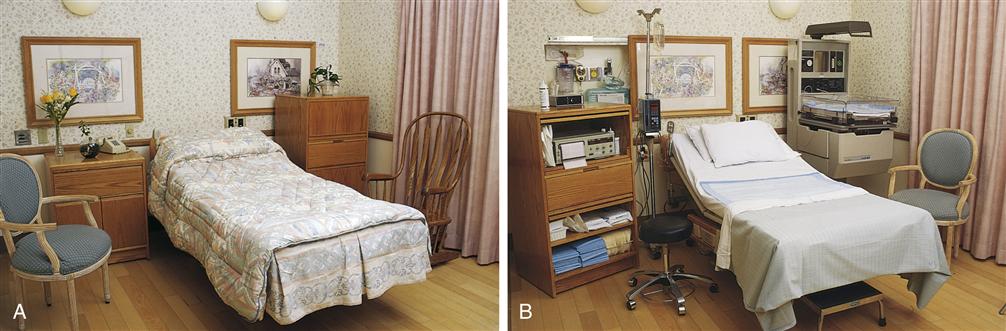

Labor, Delivery, and Recovery Rooms

Today most hospitals offer alternative settings for childbirth. The most common is the labor, delivery, and recovery (LDR) room. In an LDR room, labor, birth, and early recovery from childbirth occur in one setting. Furniture has a less institutional appearance but can be quickly converted into the setup needed for birth. A typical LDR room is illustrated in Figure 1-1.

Home-like furnishings (A) can be adapted quickly to reveal needed technical equipment (B).

During labor, significant others of the woman’s preference may remain with her. The nurse often finds it necessary to regulate visitors in and out of the room to maintain safety and patient comfort. The mother typically remains in the LDR room 1 to 2 hours after vaginal birth for recovery and then is transferred to the postpartum unit. The infant usually stays with the mother throughout her stay in the LDR room. The infant may be transferred to the nursery or may remain with the mother after her transfer to a postpartum room. Couplet care, or assignment of one nurse to the care of both mother and baby, is common in today’s postpartum units. The father or another primary support person is encouraged to stay with the mother and infant, and many facilities provide beds so they can stay through the night.

The major advantages of LDR rooms are that the setting is more comfortable and the family can remain with the mother. Disadvantages include the routine (rather than selective) use of technology, such as electronic fetal monitoring and the administration of intravenous fluids.

Labor, Delivery, Recovery, and Postpartum Rooms

Some hospitals offer rooms that are similar to LDR rooms in layout and in function, but the mother is not transferred to a postpartum unit. She and the infant remain in the labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum (LDRP) room until discharge. Frequent disadvantages of LDRP include a noisy environment and birthing beds that are less comfortable than standard hospital beds having a single mattress. Many hospitals have worked with the unit design so they have a group of beds in one area of the unit that are all postpartum.

Birth Centers

Free-standing birth centers provide maternity care outside the acute-care setting to low-risk women during pregnancy, birth, and postpartum. Most provide gynecologic services such as annual checkups and contraceptive counseling. Both the mother and infant continue to receive follow-up care during the first 6 weeks. This may include help with breastfeeding, a postpartum examination at 4 to 6 weeks, family planning information, and examination of the newborn. Care is often provided by certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) who are registered nurses with advanced preparation in midwifery.

Birth centers are less expensive than acute-care hospitals, which provide advanced technology that may be unnecessary for low-risk women. Women who want a safe, homelike birth in a familiar setting with staff they have known throughout their pregnancies express a high rate of satisfaction.

The major disadvantage is that most freestanding birth centers are not equipped for obstetric emergencies. Should unforeseen difficulties develop during labor, the woman must be transferred by ambulance to a nearby hospital to the care of a back-up physician who has agreed to perform this role. Some families do not feel that the very short stay after birth, often less than 12 hours, allows enough time to detect early complications in mother and infant.

Home Births

In the United States only a small number of women have their babies at home. Because malpractice insurance for midwives attending home births is expensive and difficult to obtain, the number of midwives who offer this service has decreased greatly.

Home birth provides the advantages of keeping the family together in their own environment throughout the childbirth experience. Bonding with the infant is unimpeded by hospital routines, and breastfeeding is encouraged. Women and their support person have a sense of control because they actively plan and prepare for each detail of the birth.

Giving birth at home also has disadvantages. The woman must be screened carefully to make sure that she has a very low risk for complications. If transfer to a nearby hospital becomes necessary, the time required may be too long in an emergency. Other problems of home birth may include the need for the parents to provide an adequate setting and supplies for the birth if the midwife does not provide supplies. The mother must care for herself and the infant without the professional help she would have in a hospital setting.

Nursing of Children

To better understand contemporary child health nursing, the nurse needs to understand the history of this field, trends and issues affecting contemporary practice, and the ethical and legal frameworks within which pediatric nursing care is provided.

Historical Perspectives

The nursing care of children has been influenced by multiple historical and social factors. Children have not always enjoyed the valued position that they hold in most families today. Historically, in times of economic or social instability, children have been viewed as expendable. In societies in which the struggle for survival is the central issue and only the strongest survive, the needs of children are secondary. The well-being of children in the past depended on the economic and cultural conditions of the society. At times, parents have viewed their children as property, and children have been bought and sold, beaten, and, in some cultures, sacrificed in religious ceremonies. At times, infanticide has been a routine practice. Conversely, in other instances, children have been highly valued and their birth considered a blessing. Viewed by society as miniature adults, children in the past received the same remedies as adults and, during illness, were cared for at home by family members, just as adults were.

Societal Changes

On the North American continent, as European settlements expanded during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, children were valued as assets to the community because of the desire to increase the population and share the work. Public schools were established, and the courts began to view children as minors and protect them accordingly. Devastating epidemics of smallpox, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and measles took their toll on children in the eighteenth century. Children often died of these virulent diseases within 1 day.

The high mortality rate in children led some physicians to examine common child-care practices. In 1748, William Cadogan’s “Essay Upon Nursing” discouraged unhealthy child-care practices, such as swaddling infants in three or four layers of clothing and feeding them thin gruel within hours after birth. Instead, Cadogan urged mothers to breastfeed their infants and identified certain practices that were thought to contribute to childhood illness. Unfortunately, despite the efforts of Cadogan and others, child-care practices were slow to change. Later in the eighteenth century, the health of children improved with certain advances such as inoculation against smallpox.

In the nineteenth century, with the flood of immigrants to eastern American cities, infectious diseases flourished as a result of crowded living conditions; inadequate and unsanitary food; and harsh working conditions for men, women, and children. It was common for children to work 12- to 14-hour days in factories, and their earnings were essential to the survival of the family. The most serious child health problems during the nineteenth century were caused by poverty and overcrowding. Infants were fed contaminated milk, sometimes from tuberculosis-infected cows. Milk was carried to the cities and purchased by mothers with no means to refrigerate it. Infectious diarrhea was a common cause of infant death.

During the late nineteenth century, conditions began to improve for children and families. Lillian Wald initiated public health nursing at Henry Street Settlement House in New York City, where nurses taught mothers in their homes. In 1889, a milk distribution center opened in New York City to provide uncontaminated milk to sick infants.

Hygiene and Hospitalization

The discoveries of scientists such as Pasteur, Lister, and Koch, who established that bacteria caused many diseases, supported the use of hygienic practices in hospitals and foundling homes. Hospitals began to require personnel to wear uniforms and limit contact among children in the wards. In an effort to prevent infection, hospital wards were closed to visitors. Because parental visits were noted to cause distress, particularly when parents had to leave, parental visitation was considered emotionally stressful to hospitalized children. In an effort to prevent such emotional distress and the spread of infection, parents were prohibited from visiting children in the hospital. Because hospital care focused on preventing disease transmission and curing physical diseases, the emotional health of hospitalized children received little attention.

During the twentieth century, as knowledge about nutrition, sanitation, bacteriology, pharmacology, medication, and psychology increased, dramatic changes in child health occurred. In the 1940s and 1950s, medications such as penicillin and corticosteroids and vaccines against many communicable diseases saved the lives of tens of thousands of children. Technologic advances in the 1970s and 1980s, which led to more children surviving conditions that had previously been fatal (e.g., cystic fibrosis), resulted in an increasing number of children living with chronic disabilities. An increase in societal concern for children brought about the development of federally supported programs designed to meet their needs, such as school lunch programs, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Medicaid (see Table 1-1) under which the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment program was implemented.

Development of Family-Centered Child Care

Family-centered child health care developed from the recognition that the emotional needs of hospitalized children usually were unmet. Parents were not involved in the direct care of their children. Children were often unprepared for procedures and tests, and visiting was severely controlled and even discouraged.

Family-centered care is based on a philosophy that recognizes and respects the pivotal role of the family in the lives of both well and ill children. It strives to support families in their natural caregiving roles and promotes healthy patterns of living at home and in the community. Finally, parents and professionals are viewed as equals in a partnership committed to excellence at all levels of health care.

Most health care settings have a family-centered philosophy in which families are given choices, provide input, and are given information that is understandable by them. The family is respected, and its strengths are recognized.

The Association for the Care of Children’s Health (ACCH), an interdisciplinary organization, was founded in 1965 to provide a forum for sharing experiences and common problems and to foster growth in children who must undergo hospitalization. Today the organization has broadened its focus on child health care to include the community and the home.

Through the efforts of ACCH and other organizations, increasing attention has been paid to the psychological and emotional effects of hospitalization during childhood. In response to greater knowledge about the emotional effects of illness and hospitalization, hospital policies and health care services for children have changed. Twenty-four-hour parental and sibling visitation policies and home care services have become common. The psychological preparation of children for hospitalization and surgery has become standard nursing practice. Many hospitals have established child life programs to help children and their families cope with the stress of illness. Shorter hospital stays, home care, and day surgery also have helped minimize the emotional effects of hospitalization and illness on children.

Current Trends in Child Health Care

During recent years the government, insurance companies, hospitals, and health care providers have made a concerted effort to reform health care delivery in the United States and to control rising health care costs. This trend has involved a change in where and how money is spent. In the past, most of the health care budget was spent in acute care settings, where the facility charged for services after the services were provided. Because hospitals were paid for whatever materials and services they provided, they had no incentive to be efficient or cost conscious. More recently, the focus has been on health promotion, the provision of care designed to keep people healthy and prevent illness.

In late 2010, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) launched Healthy People 2020, a comprehensive, nationwide health promotion and disease-prevention agenda that builds on groundwork initiated 30 years ago. Developed with input from widely diverse constituencies, Healthy People 2020 expands on goals and objectives developed for Healthy People 2010. Although a major focus of Healthy People 2010 was reducing disparities and increasing access to care, Healthy People 2020 reemphasizes that goal and expands it to address “determinants of health,” or those factors that contribute to keeping people healthy and achieving high quality of life (USDHHS, 2010b). See www.healthypeople.gov to see and download objectives. Many of the national health objectives in Healthy People 2020 are applicable to children and families. In fact, among the 13 new and additional topic areas, 2, Adolescent Health and Early and Middle Childhood, are specifically directed to the health of children and adolescents. Benchmarks that will evaluate progress toward achieving the Healthy People 2020 objectives are called “Foundation Health Measures” and these include general health status, health-related quality of life and well-being, determinants of health, and presence of disparities (USDHHS, 2010b). National data measuring the objectives are gathered from federal and state departments and from voluntary private, nongovernmental organizations.

The focus of nursing care of children has changed as national attention to health promotion and disease prevention has increased. Even acutely ill children have only brief hospital stays because increased technology has facilitated parents’ ability to care for children in the home or community setting. Most acute illnesses are managed in ambulatory settings, leaving hospital admission for the extremely acutely ill or children with complex medical needs. Nursing care for hospitalized children has become more specialized, and much nursing care is provided in community settings such as schools and outpatient clinics.

Cost Containment

Recently, the government, insurance companies, hospitals, and health care providers have made a concerted effort to reform health care delivery in the United States and control rising costs. This trend has involved a change in where and how money is spent.

One way in which those paying for health care have attempted to control costs is by shifting to a prospective form of payment. In this arrangement, patients no longer pay whatever charges the hospital determines for service provided. Instead, a fixed amount of money is agreed to in advance for necessary services for specifically diagnosed conditions. Any of several strategies have been used to contain the cost of services.

Diagnosis-Related Groups

Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) are a method of classifying related medical diagnoses based on the amount of resources that are generally required by the patient. This method became a standard in 1987, when the federal government set the amount of money that would be paid by Medicare for each DRG. If the facility delivers more services or has greater costs than what it will be reimbursed for by Medicare, the facility must absorb the excess costs. Conversely, if the facility delivers the care at less cost than the payment for that DRG, the facility keeps the remaining money. Health care facilities working under this arrangement benefit financially if they can reduce the patient’s length of stay and thereby reduce the costs for service. Although the DRG system originally applied only to Medicare patients, most states have adopted the system for Medicaid payments, and most insurance companies use a similar system.

Managed Care

Health insurance companies also examined the cost of health care and instituted a health care delivery system that has been called managed care. Examples of managed care organizations are health maintenance organizations (HMOs), point of service plans (POSs), and preferred provider organizations (PPOs). HMOs provide relatively comprehensive health services for people enrolled in the organization for a set fee or premium. Similarly, PPOs are groups of health care providers who agree to provide health services to a specific group of patients at a discounted cost. When a patient needs medical treatment, managed care includes strategies such as payment arrangements and preadmission or pretreatment authorization to control costs.

Managed care, provided appropriately, can increase access to a full range of health care providers and services for women and children, but it must be closely monitored. Nurses serve as advocates in the areas of preventive, acute, and chronic care for women and children. The teaching time lines for preventive and home care have been shortened drastically, and the call to “begin teaching the moment the child or woman enters the health care system” has taken on a new meaning. Women, parents of the child, and other caregivers are being asked to do procedures at home that were once done by professionals in a hospital setting. Systems must be in place to monitor adherence, understanding, and the total care of a patient. Assessment and communication skills need to be keen, and the nurse must be able to work with specialists in other disciplines.

Capitated Care

Capitation may be incorporated into any type of managed care plan. In a pure capitated care plan, the employer (or government) pays a set amount of money each year to a network of primary care providers. This amount might be adjusted for age and sex of the patient group. In exchange for access to a guaranteed patient base, the primary care providers agree to provide general health care and to pay for all aspects of the patient’s care, including laboratory work, specialist visits, and hospital care.

Capitated plans are of interest to employers as well as the government because they allow a predictable amount of money to be budgeted for health care. Patients do not have unexpected financial burdens from illness. However, patients lose most of their freedom of choice regarding who will provide their care. Providers can lose money (1) if they refer too many patients to specialists, who may have no restrictions on their fees, (2) if they order too many diagnostic tests, or (3) if their administrative costs are too high. Some health care providers and consumers fear that cost constraints might affect treatment decisions.

Effects of Cost Containment

Prospective payment plans have had major effects on maternal and infant care, primarily in relation to the length of stay. Mothers who have a normal vaginal birth are typically discharged from the hospital at 48 hours after birth and 96 hours for cesarean births, unless the woman and her health care provider choose an earlier discharge time. This leaves little time for nurses to adequately teach new parents newborn care and to assess infants for subtle health issues. Nurses find providing adequate information about infant care is especially difficult when the mother is still recovering from childbirth. Problems with earlier discharge of mother and infant often require readmission and more expensive treatment than might have been needed if the problem had been identified early.

Another concern in regard to cost containment is that some children with chronic health conditions have been denied care or denied insurance coverage because of preexisting conditions. Denying care can worsen a child’s condition, resulting in higher cost for the health care system, not to mention greater emotional cost for the child and family.

Despite efforts to contain costs related to the provision of health care in the United States, the percentage of the total government expenditures for services (gross domestic product [GDP]) allocated to health care was 17.6% in 2009, markedly higher than many similar developed countries (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, 2011; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011). This percentage has nearly doubled since 1980 and, without true health care reform, is expected to continue to increase.

In March 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was signed into law. Designed to rein in health care costs while increasing access to the underserved, provisions of this law are to be phased in over the course of 4 years (USDHHS, 2011b). In general, improved access will occur through access to affordable insurance coverage for all citizens. Persons who do not have access to insurance coverage through employer-provided insurance plans will be able to purchase insurance through an insurance exchange, which will offer a variety of coverage options at competitive rates (USDHHS, 2011b). Several of the provisions of this law specifically address the needs of children and families. They include the following (USDHHS, 2011b):

• Keeping young adults on their family’s health insurance plan until age 26 years

• Coordinated management for children and other individuals with chronic diseases

• Expanding the number of community health centers

• Increasing access to preventive health care

• Providing for home visits to pregnant women and newborns

• Supporting states to expand Medicaid coverage

• Providing additional funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

An additional provision of the Affordable Care Act is the creation of accountable care organizations (ACOs). These are groups of hospitals, physicians’ offices, community agencies, and any agency that provides health care to patients. Enhancing patient-centered care, the ACO collaborates on all aspects of coordination, safety, and quality for individuals within the organization. The ACO will reduce duplication of services, decrease fragmentation of care, and give more control to patients and families (USDHHS, 2011a).

Cost containment measures have also altered traditional ways of providing patient-centered care. There is an increased focus on ensuring quality and safety through such approaches as case management, use of clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based nursing care, and outcomes management.

Case Management

Case management is a practice model that uses a systematic approach to identify specific patients, determine eligibility for care, arrange access to appropriate resources and services, and provide continuity of care through a collaborative model (Lyon & Grow, 2011). In this model, a case manager or case coordinator, who focuses on both quality of care and cost outcomes, coordinates the services needed by the patient and family. Inherent to case management is the coordination of care by all members of the health care team. The guidelines established in 1995 by the Joint Commission require an interdisciplinary, collaborative approach to patient care. This concept is at the core of case management. Nurses who provide case management evaluate patient and family needs, establish needs documentation to support reimbursement, and may be part of long-term care planning in the home or a rehabilitation facility.

Evidence-Based Nursing Care

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a branch of the U.S. Public Health Service, actively sponsors research in health issues facing mothers and children. From research generated through this agency, as well as others, high-quality evidence can be accumulated to guide the best and lowest cost clinical practices. Focus of research from AHRQ is primarily on access to care for mothers, infants, children, and adolescents. This includes such topics as timeliness of care (care is provided as soon as necessary), patient centeredness (quality of communication with providers), coordination of care for children with chronic illnesses, access to a medical home, and safe medication delivery systems (AHRQ, 2011). Effectiveness of health care also is a priority for research funding; this focus area includes immunizations, preventive vision care, preventive dental care, weight monitoring, and mental health and substance abuse monitoring (AHRQ, 2011). Clinical practice guidelines are an important tool in developing parameters for safe, effective, and evidence-based care for mothers, infants, children, and families. AHRQ has developed several guidelines related to adult and child care, as have other organizations and professional groups concerned with children’s health. Important children’s health issues, which include quality and safety improvements, enhanced primary care, access to quality care, and specific illnesses, are addressed in available practice guidelines. For detailed information, see the website at www.ahcpr.gov or www.guidelines.gov.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011) has published standards for developing practice guidelines to maximize the consistency within and among guidelines, regardless of guideline developers. The IOM recommends inclusion of important information and process steps in every guideline. This includes ensuring diversity of members of a clinical guideline group; full disclosure of conflict of interest; in-depth systematic reviews to inform recommendations; providing a rationale, quality of evidence, and strength of recommendation for each recommendation made by the guideline committee; and external review of recommendations for validity (IOM, 2011). Standardization of clinical practice guidelines will strengthen evidence-based care, especially for guidelines developed by nurses or professional nursing organizations.

Outcomes Management

The determination to lower health care costs while maintaining the quality of care has led to a clinical practice model called outcomes management. This is a systematic method to identify outcomes and to focus care on interventions that will accomplish the stated outcomes for children with specific issues, such as the child with asthma.

Nurse Sensitive Indicators

In response to recent efforts to address both quality and safety issues in health care, various government and privately funded groups have sponsored research to identify patient care outcomes that are particularly dependent on the quality and quantity of nursing care provided. These outcomes, called nurse sensitive indicators, are based on empirical data collected by such organizations as the AHRQ and the National Quality Forum (NQF), and represent outcomes that improve with optimal nursing care (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2011; Lacey, Smith, & Cox, 2008). The following are in the process of development and delineation for pediatric nurses: adequate pain assessment, peripheral intravenous infiltration, pressure ulcer, catheter-related bloodstream infection, smoking cessation for adolescents, and obesity (ANA, 2011; Lacey et al. 2008). Nurses need to use evidence-based intervention to improve these patient outcomes.

Variances

Deviations, or variances, can occur in either the time line or in the expected outcomes. A variance is the difference between what was expected and what actually happened. A variance may be positive or negative. A positive variance occurs when a child progresses faster than expected and is discharged sooner than planned. A negative variance occurs when progress is slower than expected, outcomes are not met within the designated time frame, and the length of stay is prolonged.

Clinical Pathways

One planning tool used by the health care team to identify and meet stated outcomes is the clinical pathway. Other names for clinical pathways include critical or clinical paths, care paths, care maps, collaborative plans of care, anticipated recovery paths, and multidisciplinary action plans. Clinical pathways are standardized, interdisciplinary plans of care devised for patients with a particular health problem. The purpose, as in managed care and case management, is to provide quality care while controlling costs. Clinical pathways identify patient outcomes, specify time lines to achieve those outcomes, direct appropriate interventions and sequencing of interventions, include interventions from a variety of disciplines, promote collaboration, and involve a comprehensive approach to care. Home health agencies use clinical pathways, which may be developed in collaboration with hospital staff.

Clinical pathways may be used in various ways. For example, they may be used for change-of-shift reports to indicate information about length of stay, individual needs, and priorities of the shift for each patient. They also may be used for documentation of the person’s nursing care plan and his or her progress in meeting the desired outcomes. The clinical pathway for a new mother may include care of her infant at term. Many pathways are particularly helpful in identifying families that need follow-up care.

Home Care

Home nursing care has experienced dramatic growth since 1990. Advances in portable and wireless technology, such as infusion pumps for administering intravenous nutrition or subcutaneous medications and various monitoring devices, such as telemonitors, allow nurses, and often patients or family, to perform procedures and maintain equipment in the home. Consumers often prefer home care because of decreased stress on the family when the patient is able to remain at home rather than be separated from the family support system because of the need for hospitalization. Optimal home care also can reduce readmission to the hospital for adults and children with chronic conditions.

Home care services may be provided in the form of telephone calls, home visits, information lines, and lactation consultations, among others. Online and wireless technology allows nurses to evaluate data transmitted from home. Infants with congenital anomalies, such as cleft palate, may need care that is adapted to their condition. Moreover, greater numbers of technology-dependent infants and children are now cared for at home. The numbers include those needing ventilator assistance, total parenteral nutrition, intravenous medications, apnea monitoring, and other device-associated nursing care.

Nurses must be able to function independently within established protocols and must be confident of their clinical skills when providing home care. They should be proficient at interviewing, counseling, and teaching. They often assume a leadership role in coordinating all the services a family may require, and they frequently supervise the work of other care providers.

Community Care

A model for community care of children is the school-based health center. School-based health centers provide comprehensive primary health care services in the most accessible environment. Students can be evaluated, diagnosed, and treated on site. Services offered include primary preventive care, including health assessments, anticipatory guidance, vision and hearing screenings, and immunizations; acute care; prescription services; and mental health and counseling services. Some school-based health centers are sponsored by hospitals, local health departments, and community health centers. Many are used in off hours to provide health care to uninsured adults and adolescents.

Access to Care

Access to care is an important component when evaluating preventive care and prompt treatment of illness and injuries. Access to health care is strongly associated with having health insurance. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 2010) has issued a policy statement that states, “All children must have access to affordable and comprehensive quality care” (p. 1018). This care should be ensured through access to comprehensive health insurance that can be carried to wherever the child and family reside, provide continuous coverage, and allow for free choice of health providers (AAP, 2010).

Having health insurance coverage, usually employer sponsored, often determines whether a person will seek care early in the course of a pregnancy or an illness. Many private health plans have restrictions such as prequalification for procedures, drugs that the plan covers, and services that are covered. People with employer-sponsored health insurance often find that they must change providers each year because the available plans change, a situation that may negatively affect the provider-patient relationship. As the Affordable Care Act is phased in over the next few years, these issues may be resolved.

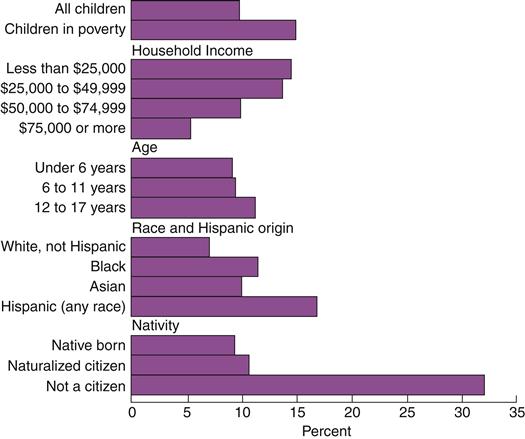

Public Health Insurance Programs

Despite improvements in federal and state programs that address children’s health needs, the number of uninsured children in the United States was 7.5 million in 2009 (most recent figure reported); this represents 10% of children younger than age 18 (Figure 1-2). Health insurance coverage varies among children by poverty, age, race, and ethnic origin (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2010). The proportion of children with health insurance is lowest among Hispanic children compared with white children and lower among poor, near-poor, and middle-income children compared with high-income children (Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011). Nearly 23% of children in the United States are underinsured, meaning that their resources are not sufficient to meet their health care needs (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], 2010a).

Federal surveys now give respondents the option of reporting more than one race. This figure shows data using the race-alone concept. For example, Asian refers to people who reported Asian and no other race. (From DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., Smith J. C., U.S. Census Bureau. [2010]. Current population reports: Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009, P60-238, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.)

Children in poor and near-poor families are more likely to be uninsured (15.1%) (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2010), have unmet medical needs, receive delayed medical care, have no usual provider of health care, and have higher rates of emergency room service than children in families that are not poor. Greater than 6% of all children have no usual place of health care (Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011).

Public health insurance for children is provided primarily through Medicaid, a federal program that provides health care for certain populations of people living in poverty, or the CHIP (formerly the State Children’s Health Insurance Program), a program that provides access for children not poor enough to be eligible for Medicaid, but whose household income is less than 200% of poverty level. In 2009, funding was renewed for CHIP through the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA); since that time, the number of children insured by Medicaid and CHIP increased by 2.6 million (USDHHS, 2010a).

Medicaid covered 34.5% of children younger than age 18 years in 2009 (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2011). Medicaid provides health care for the poor, aged, and disabled, with pregnant women and young children especially targeted. Medicaid is funded by both the federal government and individual state governments. The states administer the program and determine which services are offered.

Preventive Health

Oral health of children in the United States has become a topic of increasing focus. Services available through Medicaid are limited, and many dentists do not accept children who are insured by Medicaid. Racial and ethnic disparities exist in this area of health, with a high percentage of non-Hispanic Black school-age children and Mexican-American children having untreated dental caries as compared to non-Hispanic white children (Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011). In addition, maternal periodontal disease is emerging as a contributing factor to prematurity, with its adverse effects on the child’s long-term health.

Besides the obvious implication of not having health insurance—the inability to pay for health care during illness—another important effect on children who are not insured exists: They are less likely to receive preventive care such as immunizations and dental care. This places them at increased risk for preventable illnesses and, because preventive health care is a learned behavior, these children are more likely to become adults who are less healthy.

Health Care Assistance Programs

Many programs, some funded privately, others by the government, assist in the care of mothers, infants, and children. The WIC program, which was established in 1972, provides supplemental food supplies to low-income women who are pregnant or breastfeeding and to their children up to the age of 5 years. WIC has long been heralded as a cost-effective program that not only provides nutritional support but also links families with other services, such as prenatal care and immunizations.

Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program was developed to provide comprehensive health care to Medicaid recipients from birth to 21 years of age. The goal of the program is to prevent health problems or identify them before they become severe. This program pays for well-child examinations and for the treatment of any medical problems diagnosed during such checkups.

Public Law 99-457 is part of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act that provides financial incentives to states to establish comprehensive early intervention services for infants and toddlers with or at risk for developmental disabilities. Services include screening, identification, referral, and treatment. Although this is a federal law and entitlement, each state bases coverage on its own definition of developmental delay. Thus coverage may vary from state to state. Some states provide care for at-risk children.

The Healthy Start program, begun in 1991, is a major initiative to reduce infant deaths in communities with disproportionately high infant mortality rates. Strategies used include reducing the number of high-risk pregnancies, reducing the number of low-birth-weight and preterm births, improving birth-weight–specific survival, and reducing specific causes of postneonatal mortality.

The March of Dimes, long an advocate for improving the health of infants and children, launched its Prematurity Campaign in 2003. Designed to reduce the devastating toll that prematurity takes on the population, the campaign emphasizes education, research, and advocacy. The incidence of prematurity increased 30% since 1981, often resulting in permanent health or developmental problems for survivors of early birth. The current percentage of babies born prematurely (less than 37 weeks) is one in every eight newborns (12.5%) in the United States (March of Dimes, 2011). Late preterm births (34 to 36 weeks) account for 70% of the preterm births and have an increased risk for early death compared with infants delivered at term (Martin et al., 2010; www.modimes.org/mission/prematurity).

Statistics on Maternal, Infant, and Child Health

Statistics are important sources of information about the health of groups of people. The newest statistics about maternal, infant, and child health for the United States can be obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (www.cdc.gov/nchs).

Maternal and Infant Mortality

Throughout history, women and infants have had high death rates, especially around the time of childbirth. Infant and maternal mortality rates began to decrease when the health of the general population improved, basic principles of sanitation were put into practice, and medical knowledge increased. A further large decrease was a result of the widespread availability of antibiotics, improvements in public health, and better prenatal care in the 1940s and 1950s. Today mothers seldom die in childbirth, and the infant mortality rate is decreasing, although the rate of change has slowed for both. Racial inequality of maternal and infant mortality rates continues, with nonwhite groups having higher mortality rates than white groups.

Maternal Mortality

In 2007, the maternal mortality rate was 10.2 per 100,000 live births for all women in the United States. Black or African-American women are more likely to die from birth-related causes than white women. The maternal mortality rate for Black women is 23.8, whereas for white women it is 7.7 (NCHS, 2011). Maternal mortality is based on complications of pregnancy, birth, and postpartum and may extend beyond 42 days.

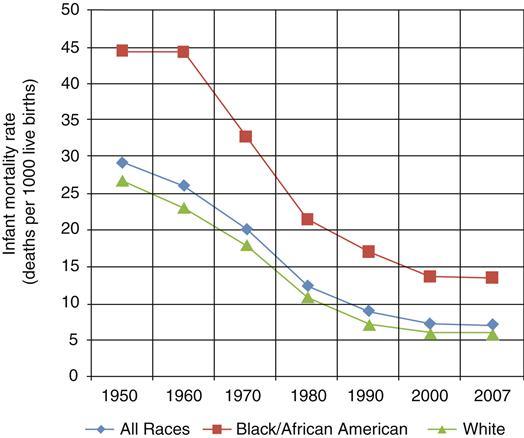

Infant Mortality

Between 1950 and 1990, infant mortality dropped from 29.2 to 9.2 deaths per 1000 live births. The infant mortality rate (death before the age of 1 year) has decreased slightly from 7 per 1000 in 2002 to 6.7 per 1000 in 2007. The neonatal mortality rate (death before 28 days of life) dropped to 4.4 deaths per 1000 live births in 2007. The five leading causes of infant mortality for 2007 include congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosome abnormalities; sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS); newborn problems related to maternal complications; and unintentional injury.

The decrease in the infant mortality rate is attributed to better neonatal care and to public awareness campaigns such as the Back to Sleep campaign to reduce the occurrence of sudden infant death syndrome. The Back to Sleep campaign, for example, has contributed to a reduction of more than 50% in the number of deaths attributed to SIDS in the United States since 1980 (Mathews & MacDorman, 2011; NCHS, 2011; Xu, Kochanek, Murphy, & Tejada-Vera, 2010).

Racial Disparity for Mortality

Although infant mortality rates in the United States have declined overall, they have declined faster for non-Hispanic white than for non-Hispanic Black infants. The mortality rate in 2007 for white infants was 5.6. For African-American infants, the rate was 13.2 (NCHS, 2011; Xu et al., 2010). Figure 1-3 compares the rates of infant mortality for all races and for whites and Blacks or African-Americans since 1950.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree