Chapter 21 Education for parenthood

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

What could the focus be for parenthood education?

Education for parenthood should be seen as part of a lifelong journey, and as a means of helping parents acquire understanding of their own social, emotional and psychological needs and those of their infants (Smith 1997). Parenting programmes form part of the early intervention services that promote positive perinatal outcomes (DH 2008a). These support the transition to parenthood particularly for new parents, in preparing them for their new roles and responsibilities. Specifically, they include enhancement of the parent–infant relationship and relationships within the family, as well as problem-solving skills, and encourage families to identify and take advantage of supportive networks within local communities (DH 2008a, Smith 1997).

‘Traditional’ parenthood education classes can and do help parents to form social networks, as they may meet others in similar circumstances. However, the focus for healthcare providers and voluntary organizations is often, in general, preparation for birth; concentrating on the physical aspects of pregnancy and possible care of the baby (Crisp 1994). Classes are often provided for women only, yet Lloyd (1999) suggests it is more effective to work with both parents. Unfortunately, as Nolan’s (2005) critical review of the literature points out, it is difficult to draw any conclusions as to the effectiveness of classes, as the quality of the research is flawed, although parents do seem to enjoy them.

Parents-to-be themselves concentrate on the physical aspects of pregnancy and managing practical aspects, such as work and childcare. The psychological impact of impending parenthood is given little or no attention (Barnes & Balber 2007). Consequently, parents complain that they are unprepared for the emotional impact of having a baby (Woollett & Parr 1997). The Child Health Promotion Programme (CHPP) (DH 2008a) is urging progression in education for parenthood to services which are evidence based and promote the health and wellbeing of children. This chapter will help practitioners to refocus their programmes to provide education for parenthood, promoting some features that will form a successful programme.

What are parents’ needs?

Often, formal parenting sessions have been designed around what professionals think women and their partners need to know (Nolan 2005). When parents are asked where they obtained their information, it is either by reading, watching television or talking to friends and family. Antenatal classes are often viewed as inaccessible (particularly for fathers or other partners), or do not include parenting. When it is addressed, it is viewed as impractical or unrealistic by parents (Coombes & Schonveld 1992, Deave & Johnson 2008, Wilkins 2006). In some areas, access to antenatal/parenting courses has been reduced or even made unavailable.

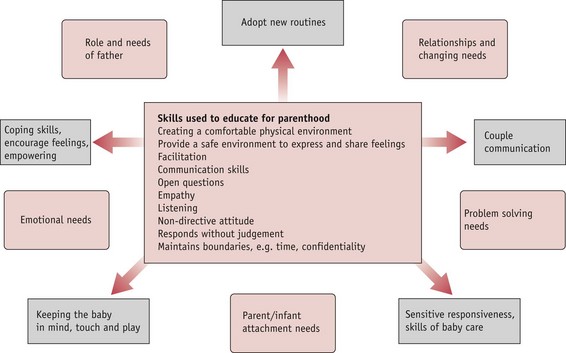

Studies investigating the needs of new parents postnatally suggest they would have liked to have been more prepared for the changing relationship between their partner and themselves (Deave & Johnson 2007) (Box 21.1, Fig. 21.1).

Parents find that their established routines are thrown into confusion, so there is a need to develop coping skills (Wilkins 2006). Fathers have great difficulty in finding a role, and classes do not always focus on their perspective, resulting in feelings of helplessness and isolation (Deave & Johnson 2007, World Health Organization 2007). Additionally, it is more effective to work with both parents, not just mothers (Lloyd 1999). Nolan (1997) also found antenatal classes were often deficient in covering postnatal issues and parents also wanted practical aspects of baby care included. It is also important to be aware of different family patterns, and their particular needs, such as lesbian mothers and their partners (RCM 2000).

In addition to the needs of parents, the Child Health Promotion Programme (CHPP) (DH 2008a) report asks that professionals empower parents through a focus on their strengths and promotion of self-knowledge. This recognizes their expertise in personal self-knowledge and knowledge of their new infant, with finally promotion of their attachment, which encourages empathy and sensitive responsiveness towards their infant. This attunement to infants and development of attachment leads to loved and loving individuals, who do not become antisocial individuals. The Worldwide Alternatives to Violence (WAVE) Trust report (WAVE Trust 2005) summarizes the importance of this intervention and outlines the brain development that can be impaired when parenting is not good enough. As such, this also promotes the mental wellbeing of future generations, one of the goals of the Darzi report (DH 2008b).

The CHPP (DH 2008a) cites several programmes that seem to meet both the needs of parents and the government recommendations in promoting attachment, the only one in the antenatal period being First steps in parenting (Parr 1996, 1998, Parr & Joyce 2009). Probably the most important determinant of programmes such as this, is the quality and skills of the practitioners who deliver them. It is imperative that midwives learn group work skills, how to facilitate rather than teach, and develop the ability to communicate with sensitive responsiveness (Deane-Gray 2008). This investment in practitioners has been demonstrated as making a considerable difference when working with new parents (Douglas & Brennan 2004).

Parent education and group work

Group facilitation is not generally part of pre-registration midwifery programmes, though some students learn presentation and seminar skills. Consequently, the style often adopted in classes can be directive, with a high level of ‘teacher’ input and a low level of acceptance of ideas, behaviours and feelings. Closed questions are often used, which do not invite discussion or sharing of feelings, and so parents’ responses become restricted (Underdown 1998). This suggests that assessment of the amount the ‘leader’ speaks in relation to the group members is a useful indicator as to how successful the leader is in facilitating and encouraging group interaction when delivering parent education.

Effective facilitation

Ockenden (2002) suggest that facilitators listen first and then consider informing. Listening involves noticing and reflecting on the message underlying the question asked (Deane-Gray 2008). What are the parents really asking? For example, ‘What would you suggest for backache?’, may really be a concern that the pregnancy is normal, or they want someone to hear how uncomfortable they are feeling and are looking for some sympathy. On the other hand, they may be seeking coping strategies as sleep is disturbed and additional work pressures are causing anxiety (Ockenden 2002). Giving an anatomical explanation or stating that back pain is normal would be a reply that missed the interpersonal cues of parents, and thus the answer provided would be one-dimensional. Part of facilitation is effective communication. In observing a group, the skill of the facilitator in listening can be ascertained by how questions are answered – sometimes by another question. An example might be managed further, by the facilitator responding to the question about backache, through asking another question, such as: ‘What is it that worries you about your backache?’ or a statement that invites the parents to talk, such as: ‘Tell me more’, or one that opens it to the group: ‘Is this a concern for others here?’ Indeed, effective communication and supporting transitions are two of the basic areas of expertise required for those working with children and their families as outlined in Every child matters (DfES 2005). The skills of group facilitation and the factors that contribute to successful groups cannot be addressed in detail in such a short chapter. Please look at the resources and recommended reading on the website for more on groups and skills to encourage interactive learning.

Group-based parenting programmes that are interactive in learning have been suggested to be most effective in supporting parents (Lloyd 1999). Parents value the interaction of sharing the recent experiences of other expectant and new parents (Wilkins 2006). Group discussions enable parents to understand that their feelings are normal and an effective group can be a strong source of non-stigmatizing support which increases parents’ confidence in their own ideas and abilities.

Learning environment

In order for parents to approach a task with confidence, it is essential that the physical and psychological climate be comfortable, so they feel enabled to direct their own learning, which is one of Knowles’ (1990) assumptions of adult learners (Box 21.2). The midwife needs to create and control the environment that assists prospective parents to direct their learning by negotiating and agree the aims and agenda of the course together with the group. Knowles (1990) also suggests as adult learners their learning is grounded in personal experience. They can build on their experiences as they orientate their learning towards the development of new tasks in their adaptation to new social roles of being parents. To facilitate this learning, it is useful to note that adults are self-motivated and have a problem-centred approach as opposed to a subject-centred approach to the acquisition of information (Knowles 1990). Using this model, the midwife (facilitator) cannot claim full control but is a joint ‘shareholder’ with the learner. The facilitator needs to adopt a non-directive role that aims to ‘make it possible (through an enabling process) for another person to achieve goals’ (Craddock 1993). This is what is truly meant by facilitation.

Box 21.2

(Based on Knowles 1990:57)

Assumptions of adult learners

Empowering is enabling parents such that they feel they lead the discussion; this gives a sense of ownership that usually leaves them feeling better equipped to make the many decisions new parenthood brings (Fig. 21.2). Wickham & Davis (2005)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree