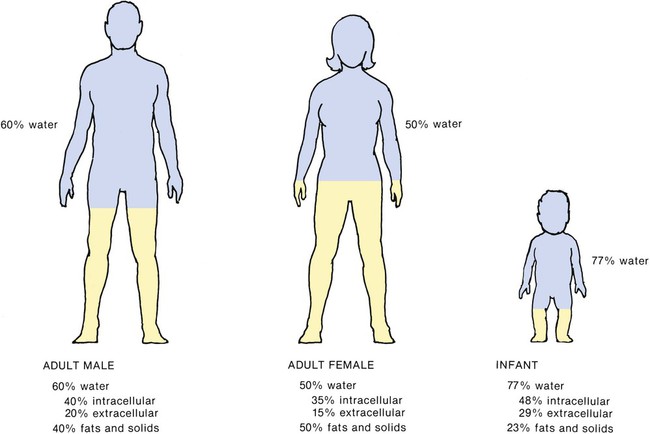

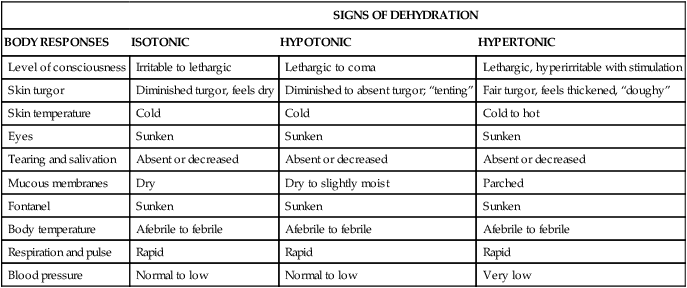

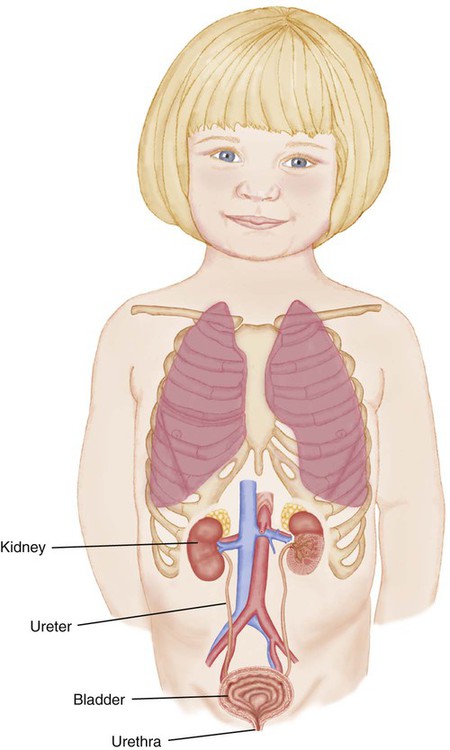

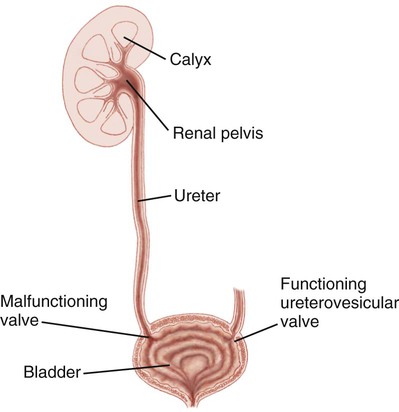

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Explain why infants and young children are more easily dehydrated than adults 3. Discuss the nursing care of the child with a urinary tract infection 4. Compare and contrast acute glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome 5. Differentiate hydrocele and cryptorchidism 6. Discuss the impact STDs have on a teenager’s life 7. Discuss the nursing care of a child with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome Infants and small children have different proportions of body water and body fat than do adults (Figure 15-1), and the water needs and water losses of the infant, per unit of body weight, are greater. In children younger than 2 years of age, the surface area is particularly important in fluid and electrolyte balance because more water is lost through the skin than through the kidneys. The surface area of the infant is two to three times greater than that of the adult in proportion to body volume or body weight. Metabolic rate and heat production are also two to three times greater in infants per kilogram of body weight. This produces more waste products, which must be diluted to be excreted. It also stimulates respiration, which causes greater evaporation through the lungs. Compared with adults, children younger than 2 years of age have a greater percentage of body water contained in the extracellular compartment. Fluid turnover is rapid, and dehydration occurs more quickly in infants than in adults. The infant cannot survive as long as the adult can in the presence of continued water depletion. A sick infant does not adapt as rapidly to shifts in intake and output because the kidneys lack maturity. Their kidneys are less able to concentrate urine and require more water than an adult’s kidneys to excrete a given amount of solute. Disturbances of the gastrointestinal tract frequently lead to vomiting and diarrhea (discussed in Chapter 14). Electrolyte balance depends on fluid balance and cardiovascular, renal, adrenal, pituitary, parathyroid, and pulmonary regulatory mechanisms. Many of these mechanisms are maturing in the developing child and are unable to react to full capacity under the stress of illness. In order to understand fluid balance and imbalance in children, it is important to understand fluid volume requirements. Box 15-1 refers to the daily maintenance fluid requirements for children. When a person is in good health, fluid intake and output balance and homeostasis (a uniform state) exist. This is accomplished by appropriate shifts of fluids and electrolytes across cellular membranes and by elimination of those products of metabolism that are no longer needed or that are in excess. The volume of blood plasma and interstitial and intracellular fluid (ICF) remains relatively constant. Dehydration occurs whenever fluid output exceeds fluid intake, regardless of the cause. The degree of dehydration and the symptoms are discussed in Box 15-2. Disorders of fluids and electrolytes (sodium [Na], potassium [K], calcium [Ca], and magnesium [Mg]) are more complex in children who are growing. A newborn infant’s total weight is approximately 78% water, compared with 60% in adults. This varies with the amount of fat. Also, the daily turnover of water in an infant is equal to almost 24% of total body water, compared with about 6% in adults. An infant’s body surface in comparison with weight is three times that of the older child; therefore the infant is subject to greater evaporation of water from the skin. The younger the child, the higher the metabolic rate and the more unstable the heat-regulating mechanisms. (Elevations in temperature are also higher, increasing the rate of water loss.) Rapid respirations speed up this process, and when diarrhea is present (see Chapter 14), additional fluid is lost in the stools. Immaturity of the kidneys impairs the infant’s ability to conserve water. Preterm and newborn infants are also more susceptible to dehydration from variations in room temperature and humidity. Cessation of intake alone can result in significant depletion. When this is coupled with higher fluid losses, life-threatening deficits can occur in a few hours. Problems of fluid and electrolyte disturbance require evaluation of the type and severity of dehydration, clinical observation of the child, and chemical analysis of the blood. Types of dehydration are classified as follows according to the amount of serum sodium: isotonic (the child has lost equal amounts of fluids and electrolytes), hypotonic (the child has lost more electrolytes than fluids), and hypertonic (the child has lost more fluids than electrolytes). These classifications are important because each form of dehydration is associated with different relative losses from intracellular fluid (ICF) and extracellular fluid (ECF) compartments, and each requires certain modifications in treatment. Maintenance therapy replaces normal water and electrolyte losses, and deficit therapy restores preexisting body fluid and electrolyte deficiencies. The replacement of a deficit may take several days, and the deficit continues unless adequate maintenance therapy is also provided. The physician calculates the volume of fluids to be administered through the use of various formulas on the basis of caloric expenditures because daily physiologic water losses are directly proportional to caloric expenditure. The child’s temperature and activity (coma, restlessness) must also be considered. Basal calories are determined by the weight of the child. Volume is calculated on a 24-hour basis. Isotonic dehydration is the most common form in children. Signs of isotonic, hypertonic, and hypotonic dehydration are discussed in Table 15-1. Table 15-1 Signs of Isotonic, Hypertonic, and Hypotonic Dehydration The renal system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra, and the renal arteries and veins. The primary functions of the urinary system includes waste excretion; maintaining homeostasis with fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance; and hormonal function (production of renin for blood pressure regulation, production of erythropoietin, and metabolism of vitamin D). The kidneys function normally at birth but are not fully developed. There is also a decrease in the ability to concentrate urine and to cope with fluid imbalances. As discussed in Chapter 5, the infant should void within the first 24 to 48 hours after birth. Urine output increases as the child ages and is monitored closely in children with renal conditions. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are caused by bacterial invasion of the upper urinary tract (kidney and ureters) or lower urinary tract (bladder and urethra). Genitourinary anatomy is reviewed in Figure 15-2. They generally occur in children between 2 and 6 years of age, unless a structural anomaly is the cause. Urinary tract infections are more commonly found in girls because the distance infectious organisms need to travel to enter the bladder is considerably shorter than in boys. Boys have a much longer urethra. Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a primary contributing factor to UTIs. As urine fills the bladder or as the bladder contracts during voiding, the opening to the ureter is normally occluded. With VUR, a malfunctioning valve at the junction of the ureter and bladder allows urine to reflux upward into the ureters toward the kidney (Figure 15-3). This allows bacteria in the urine to be carried upward, possibly all the way into the kidney. This can cause pyelonephritis and renal damage. In addition, the urine can return to the bladder, creating a residual that becomes a medium for bacterial growth or infection. VUR is graded I to V (1 to 5), with grade V involving a gross dilation of the ureter and pelvis and calyces of the kidney. Diagnosis is generally made after ultrasound and a voiding cystourethrography (VCUG). During a VCUG, contrast medium is injected into the bladder through a urethral catheter; radiographs are taken before, during, and after voiding. This procedure visualizes the bladder outline and urethra, and it identifies reflux and other structural complications. All children (1 to 10 years of age) are treated initially with antimicrobial prophylaxis. At the end of 1 year, if VUR is not resolved, endoscopy therapy is recommended for children with lower grades of reflux. Open surgery is used if endoscopy is unsuccessful; it may also be used from the outset if children have higher grades of reflux (Greenbaum and Mesrobian, 2006). Nephrotic syndrome refers to a number of different types of kidney conditions that are distinguished by the presence of marked amounts of protein in the urine. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome, idiopathic nephrosis, in which the cause is seldom determined, is discussed here because it is the most common type seen in early childhood. Table 15-2 compares poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome. Table 15-2 Comparison of (Poststreptococcal) Glomerulonephritis and (Minimal Change) Nephrotic Syndrome Data modified from Hockenberry, M., Wilson, D., Winkelstein, M., et al. (2007). Wong’s nursing care of infants and children (8th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Fluid Balance, Renal, and Reproductive Disorders

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Principles of Fluid Balance in Children

Fluid Imbalance

Dehydration

SIGNS OF DEHYDRATION

BODY RESPONSES

ISOTONIC

HYPOTONIC

HYPERTONIC

Level of consciousness

Irritable to lethargic

Lethargic to coma

Lethargic, hyperirritable with stimulation

Skin turgor

Diminished turgor, feels dry

Diminished to absent turgor; “tenting”

Fair turgor, feels thickened, “doughy”

Skin temperature

Cold

Cold

Cold to hot

Eyes

Sunken

Sunken

Sunken

Tearing and salivation

Absent or decreased

Absent or decreased

Absent or decreased

Mucous membranes

Dry

Dry to slightly moist

Parched

Fontanel

Sunken

Sunken

Sunken

Body temperature

Afebrile to febrile

Afebrile to febrile

Afebrile to febrile

Respiration and pulse

Rapid

Rapid

Rapid

Blood pressure

Normal to low

Normal to low

Very low

Renal System

Urinary Tract Infection

Vesicoureteral Reflux

Nephrotic Syndrome (Nephrosis)

MANIFESTATIONS

APSGN

MINIMAL CHANGE NEPHROTIC SYNDROME

Streptococcal antibody titers

Elevated

Normal

BP

Elevated

Normal or decreased

Edema

Periorbital and peripheral

Generalized, severe

Circulatory congestion

Common

Absent

Proteinuria

Mild to moderate

Massive

Hematuria

Gross to microscopic

Microscopic or none

BUN and serum creatinine

Elevated

Normal

Serum potassium levels

Normal or increased

Normal

Serum protein levels

Minimal reduction

Markedly decreased

Serum lipid levels

Normal

Elevated

Peak age at onset

3-7 yr

2-7 yr

Recurrence

Uncommon

Common