Financing Health Care in the United States

Joyce A. Pulcini and Mary Ann Hart

“When any human being is denied a life of dignity and respect, no matter whether they live in Anacostia or Appalachia or a village in Africa; when people are trapped in extreme poverty or are suffering from diseases we know how to prevent; when they’re going without the medicines that they so desperately need—we have more work to do.”

—Barack Obama speech at 99th NAACP Convention, July 12, 2008

Health care financing is a central issue in every discussion on problems in the health system—and was a primary driver in the 2010 health care reform legislation. The cost of health care continues to rise with poorer outcomes over the past 30 years. An aging population and the demands for chronic care are having a major impact on increasing costs. This chapter will provide a historical perspective focusing on how and why our current system has evolved to this point. The new model for health care reform will be discussed and summarized in light of evolving trends in health care financing and system design.

Historical Perspectives

Some dominant values underpin the U.S. political and economic systems. The U.S. has a long history of individualism, an emphasis on freedom to choose alternatives, and an aversion to large-scale government intervention into the private realm . Compared to other developed nations with capitalist economies, social programs have been the exception rather than the rule and have been adopted primarily during times of great need or social and political upheaval, such as in the 1930s and 1960s. Because health care in the U.S. had its origins in the private sector, partly because of the power of physicians, hospitals, and insurance companies, the degree to which government should be involved in health care remains controversial. Unlike other developed capitalist countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Switzerland, where health care is viewed as a right and considered a social good that should be available to all, the U.S. has viewed health care as a market-based commodity, readily available to those who can pay for it.

The debate over the role of government in social programs was heightened in the decades after the great depression. While the Social Security Act of 1935 brought sweeping social welfare legislation, which provided for social security payments; workman’s compensation; welfare assistance for the poor; and certain public health, maternal, and child health services, it did not provide for health care coverage for all Americans. Also, during the decade following the Great Depression in the 1930s, Blue Cross and Blue Shield (BC/BS) were developed as private insurance plans to cover hospital and physician care. The rationale that persons should pay for their medical care before they actually got sick ensured some level of security for both providers and consumers of medical services. The creation of these insurance plans effectively defused a strong political movement toward legislating a broader, compulsory government-run health insurance plan at the time (Starr, 1982). After a failed attempt by President Truman in the late 1940s to provide Americans with a national health plan, no movement occurred on this issue until the 1960s, when Medicare and Medicaid were developed.

BC/BS dominated the health insurance industry until the 1950s, when commercial insurance companies entered the market and were able to compete with BC/BS by holding down costs through excluding sicker people from insurance coverage. Over time, the distinction between BC/BS and commercial insurance companies became increasingly blurred as BC/BS offered competitive for-profit plans (Jonas & Kovner, 2005). In the 1960s, the U.S. enjoyed relative prosperity, along with a burgeoning social conscience, an appetite for change that led to a heightened concern for the poor and elderly and the impact of catastrophic illness. In response, Medicaid and Medicare, two separate but related programs, were created in 1965 by amendments to the Social Security Act. Medicare is a federal government–administered health insurance program for the disabled and those over 65, and Medicaid is a state and federal government administered health insurance program for low-income people within certain categories.

The Problem of Continual Rising Costs

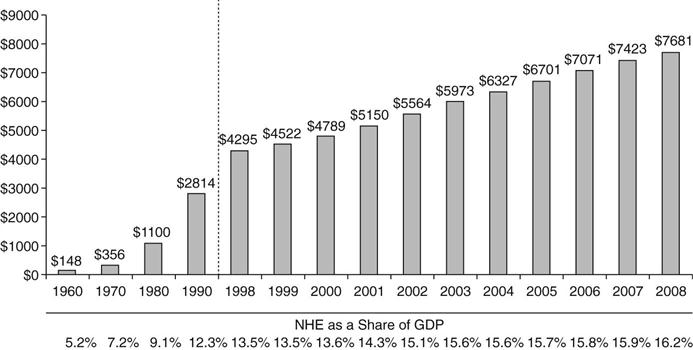

Since the 1970s, continually rising health care costs and insurance premiums have strained government budgets, become a costly expense to businesses that offer health insurance to their employees, and put health care increasingly out of reach for individuals and families. Figure 14-1 depicts the costs of health care from 1960 to 2008 (Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF], 2010d). Stakeholders in small and large businesses, government, organized labor, health care providers, and consumer groups have convened over the years to tackle the problem of rising health care costs, with little lasting success. Appendix A provides a more thorough discussion of the Affordable Care Act, its implementation as of mid-2013, and the implications for nursing.

A range of strategies have been used to curb rising health care costs over the last 40 years. Health care expenditures as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) have been increasing steadily. National health care spending reached $2.5 trillion in 2009, accounting for 17.6% of the GDP. By 2018, national health spending is expected to reach $4.4 trillion if costs are not controlled, and national health expenditures are projected to rise 6.2 percent per year as compared to a general GDP increase of 4.1% (Siska et al., 2009). Another example of increased costs is the fact that all other industrialized countries spend significantly less on health care. For example, in 2009, health care costs per capita in the U.S. were $7290 or 16% of GDP, compared to the next highest, Norway, whose comparable costs are $4763 or 11% of GDP continuing our country’s rank as number one for cost per person among industrialized nations (KFF, 2009; OECD, 2009).

Economic factors also impact health care costs and services. During the Clinton administration, universal health care legislation was introduced and failed. From 1995 to 2001, the U.S. experienced a booming economy and an unprecedented budget surplus after years of budget deficits under previous Republican administrations. In 2001, Congress approved a $1.35 trillion tax cut for higher-income Americans as recommended by President George W. Bush. This tax cut, along with a weakening economy made worse by the impact of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, plunged the U.S. into another recession. Concerns rose regarding the solvency of Medicare, the Social Security system, and an inability to contain rising health care costs.

Only about 60% of firms offered health benefits in 2009 compared to 63% in 2008. While 98% of large firms offered health insurance to employees, only 59% of small firms offered it in 2009 (KFF, HRET, 2009). Only 52% of people in the U.S. were covered by employer-based health insurance compared to 66% in 1999, with over 90% of these enrolled in a managed care organization (MCO) (KFF & HRET, 2009, p. 5; KFF, 2010b). The recession of 2008 only exacerbated the replacement of full-time jobs with health benefits to part-time jobs without health benefits, leaving more Americans uninsured. Massachusetts, in its 2006 state health reform law, has reaffirmed the responsibility of employers to provide health insurance to employees or pay a penalty fee. Establishing the concept of “shared responsibility,” it also was the first state to institute an individual mandate requiring individuals to have health insurance or pay a tax penalty.

Another option for health care reform that is being debated is employer mandates. Rising health care costs continue to impact both citizens and employers who provide health insurance for their employees. From 1999 to 2009, average health insurance premiums increased 131% and average worker contributions increased 128% over that time period, an amount much higher than inflation, which was 31.44% (KFF, 2009). The burden of higher premiums falls most heavily on those with lower incomes and on small businesses. Disproportionate shares of health care costs also fall on lower-income people further exacerbating the problem of inequities.

Why Are Costs Rising?

Multiple factors are responsible for rising health care costs as a percentage of GDP. These include financial incentives for providers to increase services created by fee-for-service payment systems, the rising cost of pharmaceuticals and health care technology, high administrative costs, fears of malpractice litigation and the practice of defensive medicine, and a disproportionate number of expensive medical specialists. Other factors include a lack of consumer knowledge of actual costs for care received, leading to inability of the market to accurately respond to cost and differential health care prices by region, type of hospital, or health care facility. For example, patients usually do not receive an itemized bill for costs incurred that are paid by insurance companies, nor do they receive information on differential costs for care by hospital or region. Future costs will also be largely determined by the aging of the population and subsequent higher health care cost utilization.

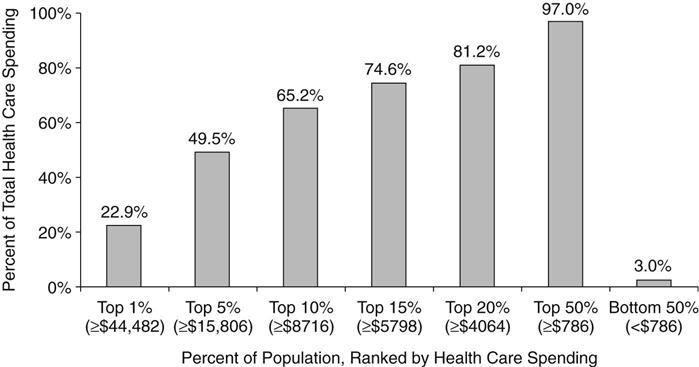

Another important factor in the rising cost of health care is the disproportionate impact of a small percentage of the population on costs. For example, from 1977 to 2007, a very stable 5% of the population, who had complex chronic illness, accounted for nearly half of the health care expenditures (Stanton, 2006; KFF, 2010d), in spite of efforts to control costs among this population. This trend continues with those in the top 1% of the population, who are most ill, spending 22.9% of health care dollars in 2007, while those in the bottom 50% spent 3% of health care dollars as shown in Figure 14-2 (KFF, 2010a). Interestingly, the majority of those in the high-expenditure group were not older adults but instead had complex chronic illnesses (Stanton, 2006). Health services research is being conducted in the area of high-cost care, but more studies are needed to explore nursing models of care delivery and their effect on cost outcomes.

Finally, as the number of uninsured has increased to more than 52 million persons in 2010 and as the population ages, the number of Medicaid enrollees, which was relatively stable for 30 years, has greatly increased (Gilmer & Kronick, 2009).

Health care costs are projected to continue to rise as the average life expectancy is extended and the “baby boomers” age and need more health services. Another factor in cost increases was the addition of coverage of prescription drugs by Medicare in 2006, as a result of the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Cost shifting is another problem that continues to plague the health care industry. For example, while Medicare spending for inpatient hospital services has been declining, outpatient costs and administrative costs have been increasing (National Coalition on Health Care, 2009).

Long-term care costs promise to be a major factor in the future, and some of these costs may be tied to the general economic trends in health care. Costs for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and home care increased rapidly, especially for the most elderly until 2007. After record-setting prices in 2007, the average price paid for skilled nursing facilities fell 17% in 2008 to $45,500 per bed, according to Levin’s report, The Senior Care Acquisition Report, (14th Edition), (2009). Along with the housing market declines, the average price for assisted living fell by 21% in 2008 to $124,900 per unit as the volume of transactions declined with the recession. The average price per unit in independent living units also fell in 2008 more than 32% to $118,100 from the 2007 high (Senior Living Business, 2009).

Cost-Containment Efforts

Over time, several approaches have been used to contain costs. None have adequately changed the trajectory of increasing costs and higher insurance premiums.

Regulation versus Competition

During the 1970s, modest government regulation attempted to contain health care costs through health planning mechanisms such as Certificate of Need (CON) programs and regional Health Systems Agencies (HSAs), which evaluated and approved applications for the construction of new facilities, beds, and new technology. During the 1980s, when proponents of competition and free market health care became politically more powerful, CON programs were weakened and HSAs were eliminated. While the free-market system has few similarities to a fully competitive market in economic terms , competition among health plans as they marketed themselves to employers in the 1980s may have slowed growth in health costs for short periods of time before they began to rise again. Co-payments, deductibles, and coinsurance are economic incentives to discourage care, putting the onus of cost-containment on the consumer/patient. However, ample research shows that low-income people may avoid necessary care when there are co-payments and deductibles. Chapter 16 focuses on economics and more fully describes the mechanisms underlying the market system in health care.

Prospective Payment versus Fee-for-Service Financing

Until the 1980s, Medicare paid providers through fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement. In FFS, providers charge a fee for each service, and then patients submit claims to their insurance company, with potentially relatively high co-payments and deductibles. According to this payment methodology, hospitals reported on their total costs for the previous year, and the federal government paid these hospitals according to their percentage of Medicare recipients, which was inherently inflationary. The federal government replaced the old system with a prospective payment system (PPS) for hospital care, establishing payment based on as diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). DRGs set a payment level for each of approximately 500 diagnostic groups typically used in inpatient care. Prospective payment measures helped to slow the rate of growth of hospital expenditures and had a major impact on length of stay and increased patient acuity in hospitals (Heffler, et al., 2001). In March 1992, physician payment reform was initiated by means of the resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS). Its goal was not only cost savings but also a redistribution of physician services to increase primary care services and decrease the use of highly specialized physicians. The Medicare program also limits the amount physicians can charge for care. In 1997, Congress instituted a prospective payment system for skilled nursing facilities and home health agencies.

Managed Care

The origins of the current managed care plans were in early prepaid health plans of the 1920s. A managed care system shifts health care delivery and payment from open-ended access to providers, paid for through fee-for-service reimbursement, toward one in which the provider is a “gatekeeper” or manager of the client’s health care and assumes some degree of financial responsibility for the care that is given. Managed care implies not only that spending will be controlled, but other aspects of care will be managed, such as price, quality, and accessibility. In managed care, the primary care provider has traditionally been the gatekeeper, deciding what specialty services are appropriate and where these services can be obtained at the lowest cost. During the 1990s, negative media regarding the restriction of services in managed care for cost savings fueled a political backlash against restrictive managed care policies. Consumer and provider demand for greater “choice” for services and access to providers have led managed care plans to become less restrictive, and also less effective in holding down the growth in health care expenditures.

Government health insurance programs such as Medicaid and Medicare also have incorporated managed care into their plans to cut costs. All fifty states offer some type of Medicaid managed care plans, and states can decide if participation is voluntary or mandatory. Some states have created state-run Medicaid-only plans, but others enroll Medicaid recipients in private managed care organizations (MCOs). By 2010, 70% of the Medicaid population received some or all of their services through Medicaid managed plans (Kaiser Health News, 2010).

During the 1990s, media attention to the concerns of consumers and providers who questioned the quality of care provided by managed care organizations (MCOs) resulted in state and federal health plan accountability laws to further regulate managed care plans (Kongstvedt, 2001). These laws included provisions for grievance procedures, confidentiality of health information, requirements that patients are fully informed of the benefits they will receive under a managed care plan, antidiscrimination clauses, and assurances that various quality mechanisms are in place so that patient satisfaction is measured and efforts to control costs do not curtail needed care. In addition, most states adopted policies giving health plan enrollees a right to appeal plan determinations involving a denial of coverage to an independent medical review entity, which is often a private organization approved by the state (American Association of Health Plans, 2001). Efforts to pass into law the federal Patient’s Bill of Rights, which contains many consumer protections related to managed care, have not been successful.

Public/Federal Funding for Health Care in the United States

In the U.S, no single public entity oversees or controls the entire health care system, making the payment for and delivery of health care complex, inefficient, and expensive. Instead, the system is composed of many public and private programs that form interrelated parts at the federal, state, and local levels. The public funding systems, which include Medicare, Medicaid, the Child Health Insurance Plan, (CHIP), the Veterans Administration (VA), and the Defense Health Program (TRICARE) for military personnel, their families, military retirees, and some others, continue to represent a larger and larger portion of health care spending. Other examples of federal programs are the Indian Health Service, which covers American Indians and Alaskan Natives, and the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program, which covers all federal employees unless excluded by law or regulation. In 2010, federal health expenditures totaled $829 billion, or 22% of all federal expenditures in that year (U.S. Government Spending, 2010). This number is expected to grow as the baby boomer population ages and becomes eligible for Medicare. Medicare outlays are projected to be $504 billion in 2010 with 46 million enrollees (KFF, 2010c). Medicaid outlays in 2009 were $378.3 billion with 60 million or one in five individuals receiving care through this program (KFF, 2010b).

Medicare

Before enactment of Medicare in 1965, older adults were more likely to be uninsured and more likely to be impoverished by excessive health care costs. Half of older Americans had no health insurance; but by 2000, 96% of seniors had health care coverage through Medicare (Federal Interagency Forum on Age-Related Statistics, 2000). Medicare and Medicaid legislation were controversial when they were debated in Congress because they were government insurance programs, but groups like the American Medical Association, who originally opposed the legislation, later benefited from these programs because older and low-income patients became insured.

Medicare had a beneficial effect on the health of older adults by facilitating access to care and medical technology, and, in 2006, prescription drug coverage helped improve the economic status of older adults. The percentage of persons over age 65 living below the poverty line decreased from 35% in 1959 (when older adults had the highest poverty rate of the population) to 9.7% in 2008 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

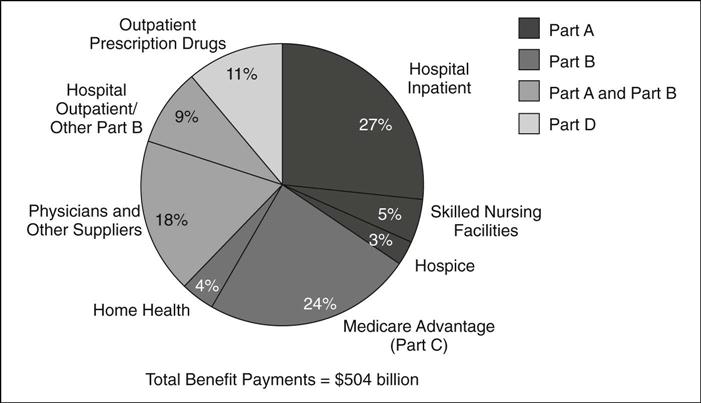

Americans are eligible for Medicare Part A at age 65, the age for Social Security eligibility or sooner, if they are determined to be disabled. Medicare Part A accounted for 35% of benefit spending in 2010 and covers 46 million Americans. Medicare Part A covers hospital and related costs and is financed through payroll deduction to the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund at the payroll tax rate of 2.9% of earnings paid by employers and employees (1.45% each) (KFF, 2010c). Medicare Part B, which accounted for 27% of benefit spending in 2010, covers 80% of the fees for physician services, outpatient medical services and supplies, home care, durable medical equipment, laboratory services, physical and occupational therapy, and outpatient mental health services (KFF, 2010c). Part B is financed through subscriber premiums and general revenue funding.

Medicare Part C or the Medicare Advantage Program, through which beneficiaries can enroll in a private health plan and also receive some extra services such as vision or hearing services, accounts for 24% of benefit spending and has more than 10 million beneficiaries (KFF, 2010c). Medicare Part D is a voluntary, subsidized outpatient drug plan with additional subsidies for low and modest income individuals. It accounts for 11% of benefit spending and enrolls more than 27 million beneficiaries (KFF, 2010c). Figure 14-3 presents Medicare benefit payments by payment type (KFF, 2010c).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree