CHAPTER 18 1. Compare and contrast the signs symptoms (clinical picture) of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. 2. Describe the biological, psychological, and environmental factors associated with eating disorders. 3. Apply the nursing process to patients with anorexia nervosa, patients with bulimia nervosa, and patients with binge-eating disorder. 4. Identify three life-threatening conditions, stated in terms of nursing diagnoses, for a patient with an eating disorder. 5. Identify two realistic outcome criteria for a patient with anorexia nervosa, a patient with bulimia nervosa, and a patient with binge-eating disorder. 6. Describe three feeding disorders usually seen in childhood, including pica, rumination disorder, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. 7. Identify the elimination disorders, enuresis and encopresis. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis The three main eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some behaviors do not meet the specifications for full-blown eating disorders but do cause problems with food intake. They are categorized under other specified feeding or eating disorder and unspecified feeding or eating disorder (Walsh & Sysko, 2009). Individuals with anorexia nervosa refuse to maintain a minimally normal weight for height and express intense fear of gaining weight. The term anorexia is a misnomer, because loss of appetite is rare. Some people with anorexia nervosa restrict their intake of food; others engage in binge eating and purging. Individuals with bulimia nervosa engage in repeated episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise. These disorders are characterized by a significant disturbance in the perception of body shape and weight (Sysko et al., 2012). Individuals with binge eating disorder engage in repeated episodes of binge eating, after which they experience significant distress. These individuals do not regularly use the compensatory behaviors that are seen in patients with bulimia nervosa. Although individuals who start binge eating may be of normal weight, repeated bingeing inevitably causes obesity in this cohort. Box 18-1 identifies characteristics of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating, and other specified feeding and eating disorders. Hospitalization for anorexia nervosa is often necessary due to the life-threatening effect that starvation has on the body. Inpatient treatment may be required for people with bulimia nervosa, especially if they have co-occurring depression and suicidal ideation. See criteria for hospitalization for these disorders in Box 18-2. People with binge eating disorder are not typically hospitalized for the eating disorder but may require psychiatric treatment for other disorders. Additionally, binge eating disorder results in a vast array of physical problems that often require inpatient treatment. For women, the lifetime incidence of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder is 0.9%, 1.5%, and 3.5%, respectively; and the lifetime incidence for men is 0.3%, 0.5%, and 2% (Hudson et al., 2007). It is extremely difficult to determine the specific number of people afflicted with eating disorders since fewer than half seek health care for their illness. With revised criteria for the eating disorders, these statistics can be expected to change in coming years. Most eating disorders begin in the early teens to mid-20s although they commonly occur following puberty, with bulimia occurring in later adolescence. Anorexia nervosa may start early (between ages 7 and 12), but bulimia nervosa is rarely seen in children younger than 12 years. Comorbidity for patients with eating disorders is more likely than not. (Treasure et al., 2010). In a replication of the National Comorbidity Survey, respondents with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder also met criteria for at least one of the core DSM IV disorders at rates of 56%, 94%, and 79%, respectively (Hudson et al., 2007). In individuals 13 to 18 years of age, anorexia nervosa is associated with oppositional defiant disorder (Swanson et al., 2011). For this age group, bulimia and binge eating mood and anxiety disorders are strongly associated with mood and anxiety disorders. Personality disorders occur more often in the eating-disordered population than the general population. In particular, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder represents only 8% of the general population but accounts for 22% of anorexia nervosa restricting type. Borderline personality disorder occurs in 6% of the general population but represents 25% of anorexia nervosa binge eating purging type and 28% of bulimia nervosa patients (Sansone & Sansone, 2011). Overeating is frequently noted as a symptom of an affective disorder (e.g., atypical depression). Higher rates of affective and personality disorders are found among binge eaters. Binge eaters report a history of major depression and anxiety disorders significantly more often than non–binge eaters, with lifetime rates of 45.3% to 65.2% (Swanson et al., 2011). Childhood trauma and sexual abuse have been reported in 20% to 50% of patients with eating disorders, and those patients with reported abuse have poorer outcomes from treatment than those who don not. Physical neglect, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse have been found to be significant predictors for eating disorders (Kong & Bernstein, 2009). The eating disorders—anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder—are actually entities or syndromes and are not considered to be specific diseases. It is not known if they share a common cause and pathology; therefore, it may be more appropriate to conceptualize them as syndromes on the basis of the cluster of symptoms they present (Halmi, 2011). A number of theories attempt to explain eating disorders. Because binge eating disorder has been newly defined, little comparative research has been done to show how this pattern of eating is similar to the others in etiology or progression. There is a strong genetic link for eating disorders. In fact, a literature search of relevant studies has suggested that the heritability of anorexia nervosa is 60% (Bienvenu et al., 2011). A genetic vulnerability may lead to poor affect and impulse control or to an underlying neurotransmitter dysfunction, but no single causative gene has been discovered to date. The most recent research suggests that there is a gene-environmental interaction that may be responsible for the prevalence of the eating disorders (Campbell et al., 2011). Research demonstrates that altered brain serotonin function contributes to dysregulation of appetite, mood, and impulse control in the eating disorders. These patients consistently exhibit personality traits of perfectionism, obsessive-compulsiveness, and dysphoric mood, all of which are modulated through serotonin pathways in the brain. Because these traits appear to begin in childhood—before the onset of actual eating-disorder symptoms—and persist into recovery, they are believed to contribute to a vulnerability to disordered eating (Kaye & Strober, 2009). Tryptophan, an amino acid essential to serotonin synthesis, is only available through diet. A normal diet boosts serotonin in the brain and regulates mood. Temporary drops in dietary tryptophan may actually relieve symptoms of anxiety and dysphoria and provide a reward for caloric restriction; however, continued malnutrition will result in a physiological dysphoria. This cycle of temporary relief, followed by more dysphoria, sets up a positive feedback loop that reinforces the disordered eating behavior (Kaye et al., 2009). This dietary need for tryptophan may account for the fact that antidepressants that boost serotonin do not improve mood symptoms until after an underweight patient has been restored to 90% of optimal weight. Newer brain imaging capabilities allow for better understanding of the etiological factors of anorexia nervosa. Much research has focused on the changes that occur in the brains of patients during the active phase of the eating disorder and after a period of recovery. Comparing brain images will help researchers to distinguish between the physiological effects of starvation and the pathology associated with the disorder (Kaye et al., 2009). Because anorexia nervosa was observed primarily in girls approaching puberty, early psychoanalytic theories linked the symptoms to an unconscious aversion to sexuality. Throughout the 20th century many authors examined the family dynamics of these patients and concluded that a failure to separate from parents and a rebellion against the maternal bond explained the disordered eating behaviors. Further work by Bruch in the 1970s explored the symptoms as a defense against an overwhelming feeling of ineffectiveness and powerlessness. Even with these theories of unconscious processes, therapies based on this understanding have not made a major impact (Caparrotta & Ghaffari, 2006). Family theorists maintain that eating disorders are a problem of the whole family, but research has not been able to determine any definitive family characteristics specific to the eating disorders. In general, family therapies focus on facilitating emotional communication and conflict resolution (le Grange et al., 2010). Studies have shown that culture influences the development of self-concept and satisfaction with body size. The Western cultural ideal that equates feminine beauty to tall, thin models has received much attention in the media as an etiology for the eating disorders. However, research has not proven a direct relationship between social ideals portrayed in the media and the development of an eating disorder. It is known that peer behaviors and attitudes may contribute to the body dissatisfaction that all eating disordered patients feel (Eisenberg & Neumark-Sztainer, 2010; Ferguson et al., 2011). The rate of obesity in the United States is at an alarming level, as 35.5% of adult women and 15% of 2- to 19-year-old girls are obese (Ogden et al., 2012). Record numbers of men and women are on diets to reduce body weight, but no study has been able to explain why only an estimated 0.3% to 3% of the population develops an eating disorder. Research has not proven a direct relationship between social ideals portrayed in the media and the development of an eating disorder; however, peer behaviors and attitudes may contribute to the body dissatisfaction that all eating-disordered patients feel (Eisenberg & Neumark-Sztainer, 2010; Ferguson et al., 2011). Anorexia nervosa is a serious psychiatric disorder. Box 18-3 lists several thoughts and behaviors associated with anorexia nervosa, and Table 18-1 identifies clinical signs and symptoms of anorexia nervosa along with their causes. TABLE 18-1 POSSIBLE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA Eating disorders are serious and in extreme cases can lead to death. Box 18-4 identifies a number of medical complications that can occur in individuals with anorexia nervosa and the laboratory findings that may result. Because the eating behaviors in these conditions are so extreme, hospitalization may become necessary (often via the emergency department). Fundamental to the care of individuals with eating disorders is establishing and maintaining a therapeutic alliance. This will take both time and diplomacy on the part of the nurse. In treating patients who have been sexually abused or who have otherwise been victims of boundary violations, it is critical that the nurse and other health care workers maintain and respect clear boundaries (Wright & Hacking, 2011). Individuals with the binge-purge type of anorexia nervosa may present with severe electrolyte imbalance (as a result of purging) and enter the health care system through admission to an intensive care unit. The patient with the restricting type of anorexia will be severely underweight and may have growth of fine, downy hair (lanugo) on the face and back. The patient will also have mottled, cool skin on the extremities and low blood pressure, pulse, and temperature readings, consistent with a malnourished, dehydrated state (see Table 18-1). Outcomes are patient-centered and should always be developed in conjunction with the person diagnosed with anorexia nervosa or someone who can represent the person. To evaluate the effectiveness of treatment, outcome criteria are established to measure treatment results. The most important outcome is in the attainment of a safe weight. Table 18-2 identifies signs and symptoms commonly experienced with anorexia nervosa, offers potential nursing diagnoses, and suggests outcomes. TABLE 18-2 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS, NURSING DIAGNOSES, AND OUTCOMES FOR ANOREXIA NERVOSA From Herdman, T. H. (Ed.), (2012). Nursing diagnoses—Definitions and classification 2012-2014. Copyright © 2012, 1994-2012 by NANDA International. Used by arrangement with John Wiley & Sons Limited; Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., Maas, M. L., & Swanson, E. (2013). Nursing outcomes classification (NOC) (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. Planning is affected by the acuity of the patient’s situation. When a patient with anorexia is experiencing extreme electrolyte imbalance or weighs below 75% of ideal body weight, the plan is to provide immediate medical stabilization, most likely in an inpatient unit. If a specialized eating-disorder unit is not available, hospitalization on a cardiac or medical unit is usually brief, providing only limited weight restoration and addressing only the acute complications (e.g., electrolyte imbalance and dysrhythmias) and acute psychiatric symptoms (e.g., significant depression). With the initiation of therapeutic nutrition, malnourished patients may need treatment on a medical unit, owing to refeeding syndrome, a potentially catastrophic treatment complication involving a metabolic alteration in serum electrolytes, vitamin deficiencies, and sodium retention (Kohn, et al., 2011) There are no drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of anorexia nervosa, and research does not support the use of pharmacological agents to treat the core symptoms (Treasure et al., 2010). The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) fluoxetine (Prozac), however, has proven useful in reducing obsessive-compulsive behavior after the patient has reached a maintenance weight. Unconventional antipsychotic agents such as olanzapine (Zyprexa) may be helpful in improving mood and decreasing obsessive behaviors and resistance to weight gain (Treasure et al., 2010) but are not well accepted by patients who are frightened by the side effect of weight gain with this classification of drugs. Patients with eating disorder may benefit by a number of complementary alternative medicine therapies (Breuner, 2010). A comprehensive treatment plan can include the usual medical and nutritional interventions along with the beneficial effects of massage, biofeedback, acupuncture, or yoga to manage mood. It is also important that the nurse ask if patients are taking herbals, such as St. John’s wort for depression, valerian for sleep, and chamomile for anxiety. Patients will need proper guidance and education to assist them when they choose to add these therapies to their recovery program. Anorexia nervosa is a chronic illness that waxes and wanes. The 1-year relapse rate approaches 50%, and long-term studies show that up to 40% of patients continue to meet some criteria for anorexia nervosa after 4 years (Helverskov et al., 2010). Recovery is evaluated as a stage in the process rather than a fixed event. Factors that influence the stage of recovery include percentage of ideal body weight that has been achieved, the extent to which self-worth is defined by shape and weight, and the amount of disruption existing in the patient’s personal life.

Feeding, eating, and elimination disorders

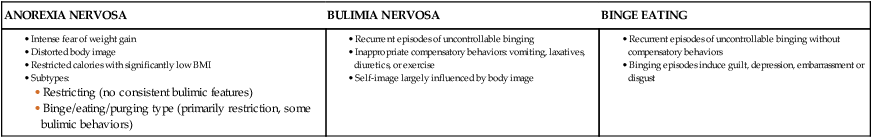

Clinical picture

Epidemiology

Comorbidity

Etiology

Biological factors

Genetic

Neurobiological

Psychological factors

Environmental factors

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CAUSE

Low weight

Caloric restriction, excessive exercising

Amenorrhea

Low weight

Yellow skin

Hypercarotenemia

Lanugo

Starvation

Cold extremities

Starvation

Peripheral edema

Hypoalbuminemia and refeeding

Muscle weakening

Starvation, electrolyte imbalance

Constipation

Starvation

Abnormal laboratory values (low triiodothyronine, thyroxine levels)

Starvation

Abnormal computed tomographic scans, electroencephalographic changes

Starvation

Cardiovascular abnormalities (hypotension, bradycardia, heart failure)

Starvation, dehydration

Electrolyte imbalance

Impaired renal function

Dehydration

Hypokalemia (low potassium)

Starvation

Anemic pancytopenia

Starvation

Decreased bone density

Estrogen deficiency, low calcium intake

General assessment

Outcomes identification

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

NURSING DIAGNOSES

OUTCOMES

Emaciation, dehydration, arrhythmias, inadequate intake, dry skin, decreased blood pressure, decreased urine output, increased urine concentration, weakness

Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirementsDecreased cardiac output

Risk for injury (electrolyte imbalance)

Risk for imbalanced fluid volume

Nutrients are ingested and absorbed to meet metabolic needs; cardiac pump supports systemic perfusion pressure; electrolytes are in balance; fluids are in balance

Excessive self-monitoring, describes self as fat despite emaciation

Disturbed body image

Congruence between body reality, body ideal, and body presentation; satisfaction with body appearance

Destructive behavior toward self, poor concentration, inability to meet role expectations, inadequate problem solving

Ineffective coping

Demonstrates effective coping, reports decrease in stress, uses personal support system, uses effective coping strategies, reports increase in psychological comfort

Indecisive behavior, lack of eye contact, passive, reports feelings of shame, rejects positive feedback about self

Chronic low self-esteemPowerlessness

Verbalizes a positive level of confidence; makes informed life decisions, expresses independence with decision-making processes

Planning

Implementation

Acute care

Pharmacological interventions

Integrative medicine

Advanced practice interventions