CHAPTER 34 Laura Cox Dzurec and Sylvia Stevens 1. Discuss the characteristics of a healthy family. 2. Differentiate between functional and dysfunctional family patterns of behavior as they relate to five universal family functions: management, boundaries, communication, emotional support, and socialization. 3. Compare and contrast insight-oriented family therapy and behavioral family therapy. 4. Identify five family theorists and their contributions to the family therapy movement. 5. Analyze the meaning and value of the family’s sociocultural context when assessing and planning intervention strategies. 6. Construct a genogram using a three-generation approach. 7. Recognize the significance of self-assessment to successful work with families. 8. Formulate outcome criteria family might develop together. 9. Identify strategies for family intervention. 10. Distinguish between the nursing intervention strategies of a basic-level nurse and those of an advanced practice nurse with regard to counseling and psychotherapy. 11. Explain the importance of the nurse’s role in psychoeducational family therapy. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Political upheaval occurring around the world highlights the importance of family relationships to the well-being of individual family members. When children are deprived of family support—for instance, in cases of loss due to the ravages of war—they tend to respond with a range of adjustment difficulties and guilt reactions that can influence their well-being for years (Reeve, 2010). This sort of loss represents the most serious cases of fractured family dynamics. Family therapy focuses on changing the interactions among the people who make up the family and on changing the character of the interactions of the family unit as a whole. As a treatment approach, family therapy began to emerge in the 1920s, as social psychologists recognized that behaviors among group members mutually influenced the behaviors of individual members (Gilgulin, 2008). The aim of family therapy is to improve the skills of the individual members and to strengthen the functioning of the family as a whole, capitalizing on the notion that parts of a whole and the whole itself mutually influence each other. More specifically, family therapists concentrate on evaluating relationships and communication patterns, structure, and rules that govern the nature of family interactions. Specific approaches to therapy vary according to the philosophical viewpoint, education, and training of individual therapists. It is fairly clear, though, that however it is practiced, family therapy is more effective for the mental health of individual family members than is treatment aimed at individuals separately (Baldwin et al., 2012). Families are defined by reciprocal relationships in which persons are committed to one another. Duvall (1957) was among early writers to describe the level of maturity of families as units. She addressed the quality of family functioning, noting that at one extreme some families function in immature or infantile ways, while at the other extreme, families may function in particularly healthy or adult-like ways. The notion of family function refers to a range of characteristics. They include the family’s: • Ability to provide for the physical and emotional safety of individual members • Quality of resources and support systems • Underlying issues such as substance abuse, domestic violence, or chronic illnesses • Established patterns of behavior and interaction • Ability to interact with support services • Relationships and interactions When Duvall described family functioning, she was referring to the “nuclear family”—mother, father, and children—that was prevalent in the 1950s. Today, family constellations are more complex. The National Health Interview Survey (Blackwell, 2010) identified the following types of families with children that exist in the United States: • Nuclear family: One or more children who live with married parents who are the biological or adoptive parents to all the children. • Single-parent family: One or more children who live with a single adult, male or female, related or unrelated to the children. • Unmarried biological or adoptive family: One or more children who live with two parents who are not married to each other and are biological or adoptive parents to all children in the family. • Blended family: One or more children living with a biological or adoptive parent and an unrelated stepparent who are married to each other. • Cohabitating family: One or more children living with a biological or adoptive parent and an unrelated adult who are cohabitating together. • Extended family: One or more children living with at least one biological or adoptive parent and a related adult who is not a parent (e.g., grandparent, adult sibling). • “Other” family: One or more children living with related or unrelated adults who are not biological or adoptive parents. This includes children living with grandparents and foster families. Still, Duvall’s descriptions of family dynamics that describe family functioning on a maturity continuum remain useful in describing family dynamics, despite the increasing complexity of family makeup. The level of functioning of the family unit, regardless of its constellation, will influence the family’s individual and collective abilities to deal with life events (Young, 2010). As the notion of family has broadened to incorporate nontraditional family structures (Figure 34-1), family therapists and counselors have been challenged to recognize and incorporate similarly broad definitions of family in their work. Despite the increasing complexity of family definitions, family health still can be measured in terms of quality of communication, consistency of familial expectations and roles, support and nurturance of one another, and adaptability in the face of change and stress (Coulter & Mullin, 2012). The family provides an essential training ground for developing individuals’ future skills for interacting in the greater community, and it is within the family that each of us initially learns sets of long-standing and fairly permanent social and emotional responses. Because family functioning represents behaviors that involve dynamics that extend beyond individuals to individuals-in-interaction, fully understanding the forces that influence family functioning is challenging. That is the challenge accepted by family therapists as they address family functioning. A healthy family provides its members with tools to guide effective functioning within the family and extends to functioning in other intimate relationships, the workplace, culture, and society in general. These tools are acquired through the activities associated with family life and include management activities, boundary delineation, communication patterns, emotional support, and socialization (Nichols, 2009). Although family therapists may use various assessment strategies, these five areas are always included. Figure 34-2 presents an assessment overview developed by Roberts (1983) that can be used to examine and measure the effectiveness of family skills in these five areas. Boundaries serve to maintain distinctions between and among individuals in the family and between the family and individuals external to it. Establishment and maintenance of flexible and appropriate boundaries is essential to healthy family functioning. Boundary management is an important skill for families and often is a primary focus of family therapists. Minuchin (1974) identified three predominant types of boundaries within families: clear, diffuse, and rigid. Clear boundaries are adaptive and healthy. They are well understood by all members of the family and give family members a sense of “I-ness” and also “we-ness.” They are firm, yet appropriately flexible, and provide a structure that responds and adapts to change. Clear boundaries allow family members to enact roles appropriately and to function without unnecessary or inappropriate interference from other members. They reflect structure and flexibility; at the same time, they support healthy family functioning and encourage growth in family members, often referred to as “differentiation” (Schnarch & Regas, 2011). In healthy families, there is a necessary and natural hierarchy, or power difference, for the protection and socialization of younger family members. Parents are the leaders in the family and children are the followers. Despite this arrangement, children can voice their opinions and have influence on family decisions. In dysfunctional families this seemingly simple equation goes off track. If the communication roles match speakers’ functional roles—when, for example, parents communicate like parents—the communication remains clear; however, if a parent communicates like a child, refusing to enact communication expected of a parent, the child may need to take on a reciprocal parental communication role, significantly confusing both communication and boundary functions (Harris, 1967; Nichols, 2009). The following vignette describes a spousal situation that shows how easily communication can be misunderstood when clear and direct messages are not sent, and Box 34-1 identifies some unhealthy communication patterns. Although there are a number of approaches useful in conducting family therapy, generally speaking, those approaches fall into one of two broad classifications or paradigms. One paradigm—Insight-Oriented Family Therapy—focuses on developing increased self-awareness, other-awareness, and family awareness among family members. The other paradigm—behavioral family therapy—focuses on changing behaviors of family members to influence overall patterns of family interactions. Table 34-1 lists specific therapies that can be classified within each paradigm, highlighting major concepts related to each individual therapy, and identifies some of the therapists who contributed to their development and use. TABLE 34-1 INSIGHT-ORIENTED AND BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Family interventions

Overview of the family

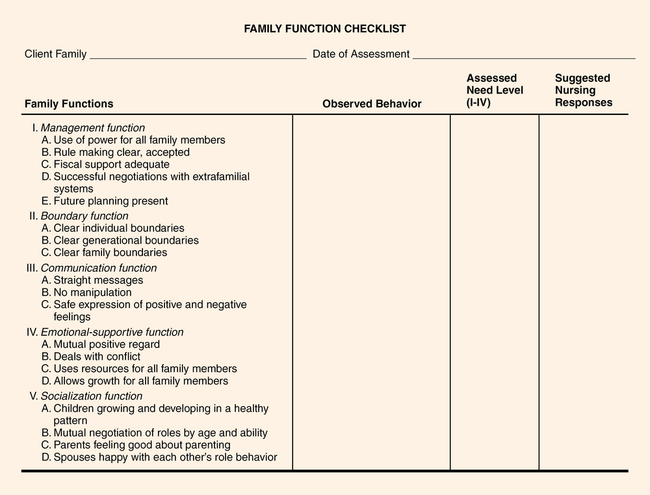

Family functions

Boundaries

Communication

Overview of family therapy

TYPE OF THERAPY

CONCEPTS

MAJOR THEORISTS

Insight-Oriented Family Therapy

Psychodynamic therapy

Problems arise from developmental arrest,current interactions, projections, and current stresses

Goal is to gain insight into problematic relationships originating in the past

Nathan Ackerman

James Framo

Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy

Family-of-origin therapy

Emphasis is on the family of origin

Family viewed as an emotional relationship system

Triangulation

Goal is to foster differentiation and decrease emotional reactivity

Murray Bowen

Experimental-existential therapy

Symptoms express family pain

Family is responsible for its own solutions

Therapist uses nurturing and identifies dysfunctional communication patterns

Goal is to encourage growth of the family

Carl Whitaker

Virginia Satir

Leslie Greenberg

Susan Johnson

Behavioral Family Therapy

Structural therapy

Focus is on organizational patterns, boundaries, systems and subsystems, and use of scapegoating

Enmeshment and disengagement

Boundaries clarification

Restructuring of dysfunctional triangles

Salvador Minuchin

Strategic therapy

Identifies inequality of power, life-cycle perspectives, and use of double-bind messages

Paradox

Prescribes rituals

Goal is to change repetitive and maladaptive interaction patterns

Jay Haley

Chloe Madanes

Milan group (Mara Palazzoli, Gianfranco Cecchin, Giuliana Prata)

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Based on learning theory

Focus is on changing cognition and behavior

Skills training is emphasized

Gerald Patterson

Richard Stuart

Robert Liberman![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Family interventions

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access