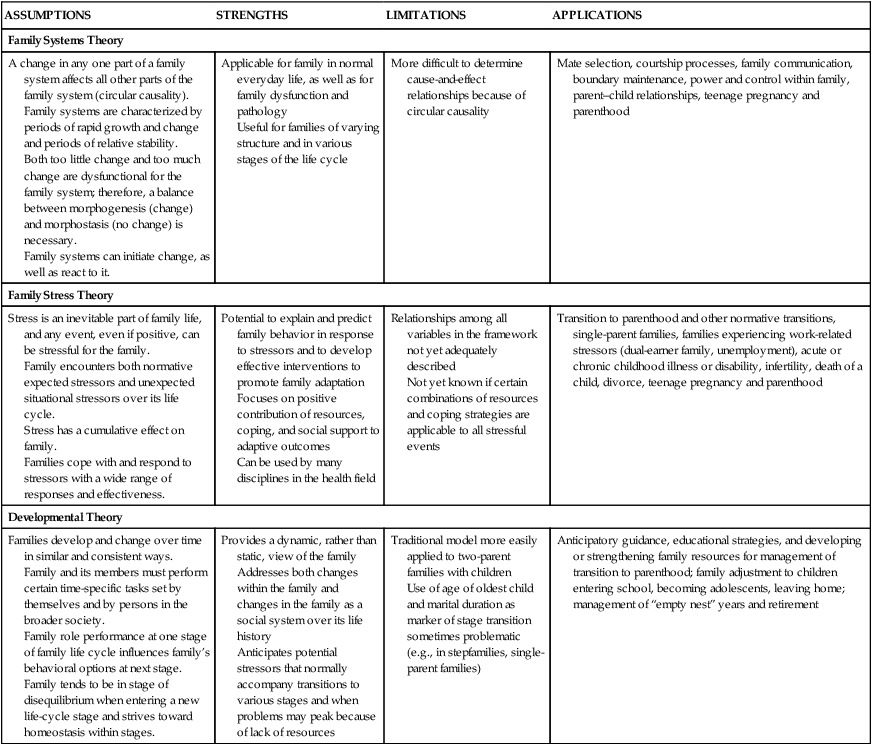

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Discuss definitions of family. • Describe three major family theories. • Identify different family structures found in the United States. • Discuss the effect of family size and configuration on personality development. • Discuss the role transition experienced by new parents. • Explain various parenting behaviors such as parenting styles, disciplinary patterns, and communication skills. • Demonstrate an understanding of special parenting situations such as adoption, divorce, single parenting, parenting in reconstituted families, and dual-earner families. http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/essentials Earlier definitions of family emphasized that family members were related by legal ties or genetic relationships and lived in the same household with specific roles. Later definitions have been broadened to reflect both structural and functional changes. A family can be defined as an institution in which individuals, related through biology or enduring commitments, and representing similar or different generations and genders, participate in roles involving mutual socialization, nurturance, and emotional commitment (Coehlo, Kaakinen, Hanson, and others, 2009). Nursing care of infants and children is intimately involved with care of the child and the family. Family structure and dynamics can have an enduring influence on a child, affecting the child’s health and well-being (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003). Consequently, nurses must be aware of the functions of the family, various types of family structures, and theories that provide a foundation for understanding the changes within a family and for directing family-oriented interventions. A family theory can be used to describe families and how the family unit responds to events both within and outside the family. Each family theory makes assumptions about the family and has inherent strengths and limitations (Coehlo, Kaakinen, Hanson, and others, 2009). Most nurses use a combination of theories in their work with children and families. Commonly used theories are family systems theory, family stress theory, and developmental theory (Table 3-1). TABLE 3-1 SUMMARY OF FAMILY THEORIES AND APPLICATIONS Family systems theory is derived from general systems theory, a science of “wholeness” that is characterized by interaction among the components of the system and between the system and the environment (Bomar, 2004). General systems theory expanded scientific thought from a simplistic view of direct cause and effect (A causes B) to a more complex and interrelated theory (A influences B, but B also affects A). In family systems theory, the family is viewed as a system that continually interacts with its members and the environment. The emphasis is on the interactions among the members; a change in one family member creates a change in other members, which in turn results in a new change in the original member. Consequently, a problem or dysfunction does not lie in any one member but rather in the type of interactions used by the family. Because the interactions, not the individual members, are viewed as the source of the problem, the family becomes the patient and the focus of care. Examples of the application of family systems theory to clinical problems are nonorganic failure to thrive and child abuse. According to family systems theory, the problem does not rest solely with the parent or child but with the type of interactions between the parent and the child and the factors that affect their relationship. Bowen’s family systems theory (Coehlo, Kaakinen, Hanson, and others, 2009) emphasizes that the key to healthy family function is the members’ ability to distinguish themselves from each other both emotionally and intellectually. The family unit has a high level of adaptability. When problems arise within the family, change occurs by altering the interaction or feedback messages that perpetuate disruptive behavior. Feedback refers to processes in the family that help identify strengths and needs and determine how well goals are accomplished. Positive feedback initiates change; negative feedback resists change (Goldenberg and Goldenberg, 2008). When the family system is disrupted, change can occur at any point in the system. A major factor that influences a family’s adaptability is its boundary, an imaginary line that exists between the family and its environment (Coehlo, Kaakinen, Hanson, and others, 2009). Family stress theory explains how families react to stressful events and suggests factors that promote adaptation to stress (Coehlo, Kaakinen, Hanson, and others, 2009). Families encounter stressors (events that cause stress and have the potential to effect a change in the family social system), including those that are predictable (e.g., parenthood) and those that are unpredictable (e.g., illness, unemployment). These stressors are cumulative, involving simultaneous demands from work, family, and community life. Too many stressful events occurring within a relatively short period (usually 1 year) can overwhelm the family’s ability to cope and place it at risk for breakdown or physical and emotional health problems among its members. When the family experiences too many stressors for it to cope adequately, a state of crisis ensues. For adaptation to occur, a change in family structure or interaction is necessary. The resiliency model of family stress, adjustment, and adaptation emphasizes that the stressful situation is not necessarily pathologic or detrimental to the family but demonstrates that the family needs to make fundamental structural or systemic changes to adapt to the situation (McCubbin and McCubbin, 1994). Developmental theory is an outgrowth of several theories of development. Duvall (1977) described eight developmental tasks of the family throughout its life span (Box 3-1). The family is described as a small group, a semiclosed system of personalities that interacts with the larger cultural social system. As an interrelated system, the family does not have changes in one part without a series of changes in other parts. In working with children, the nurse must include family members in their care plan. Research confirms parents’ desire and expectation to participate in their child’s care (Power and Franck, 2008). To discover family dynamics, strengths, and weaknesses, a thorough family assessment is necessary (see Chapter 6). The nurse’s choice of interventions depends on the theoretic family model that is used (Box 3-2). For example, in family systems theory, the focus is on the interaction of family members within the larger environment (Goldenberg and Goldenberg, 2008). In this case, using group dynamics to involve all members in the intervention process and being a skillful communicator are essential. Systems theory also presents excellent opportunities for anticipatory guidance. Because each family member reacts to every stress experienced by that system, nurses can intervene to help the family prepare for and cope with changes. In family stress theory, the nurse uses crisis intervention strategies to help family members cope with the challenging event. In developmental theory, the nurse provides anticipatory guidance to prepare members for transition to the next family stage. Nurses who think family involvement plays a key role in the care of a child are more likely to include families in the child’s daily care (Fisher, Lindhorst, Matthews, and others, 2008). The family structure, or family composition, consists of individuals, each with a socially recognized status and position, who interact with one another on a regular, recurring basis in socially sanctioned ways (Coehlo, Kaakinen, Hanson, and others, 2009). When members are gained or lost through events such as marriage, divorce, birth, death, abandonment, or incarceration, the family composition is altered, and roles must be redefined or redistributed. In many nations and among many ethnic and cultural groups, households with extended families are common. Within the extended family, grandparents often find themselves rearing their grandchildren (Fig. 3-1). Young parents are often considered too young or too inexperienced to make decisions independently. Often, the older relative holds the authority and makes decisions in consultation with the young parents. Sharing residence with relatives also assists with the management of scarce resources and provides child care for working families. A resource for extended families is the Grandparent Information Center.* In the United States, an estimated 23.8 million children lived in single-parent families (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2011). The contemporary single-parent family has emerged partially as a consequence of the women’s rights movement and also as a result of more women (and men) establishing separate households because of divorce, death, desertion, or single parenthood. In addition, a more liberal attitude in the courts has made it possible for single people, both men and women, to adopt children. Although mothers usually head single-parent families, it is becoming more common for fathers to be awarded custody of dependent children in divorce settlements. With women’s increased psychologic and financial independence and the increased acceptability of single parents in society, more unmarried women are deliberately choosing mother–child families. Frequently, these mothers and children are absorbed into the extended family. The challenges of single-parent families are discussed on p. 39. A same-sex, homosexual, or gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgender (GLBT) family is one in which there is a legal or common-law tie between two persons of the same sex who have children (Blackwell, 2007). There are a growing number of families with same-sex parents in the United States, with an estimated one fourth of all same-sex couples raising children (Pawelski, Perrin, Foy, and others, 2006). Although some children in GLBT households are biologic from a former marriage or relationship, children may be present in other circumstances. They may be foster or adoptive parents, lesbian mothers may conceive through artificial fertilization, or a gay male couple may become parents through use of a surrogate mother. Nurses need to be nonjudgmental and to learn to accept differences rather than demonstrate prejudice that can have a detrimental effect on the nurse–child–family relationship (Blackwell, 2007). Moreover, the more nurses know about the child’s family and lifestyle, the more they can help the parents and the child. Family strengths and unique functioning styles (Box 3-3) are significant resources that nurses can use to meet family needs. Building on qualities that make a family work well and strengthening family resources make the family unit even stronger. All families have strengths as well as vulnerabilities. Parental role definitions have changed as a result of the changing economy and increased opportunities for women (Bomar, 2004). As women’s role has changed, the complementary role of men has also changed. Many fathers are more active in childrearing and household tasks. As the redefinition of sex roles continues in American families, role conflicts may arise in many families because of a cultural lag of the persisting traditional role definitions. Children in a large family are able to adjust to a variety of changes and crises. There is more emphasis on the group and less on the individual (Fig. 3-2). Cooperation is essential, often because of economic necessity. The large number of people sharing a limited amount of space requires a greater degree of organization, administration, and authoritarian control. A dominant family member (a parent or older child) wields control. The number of children reduces the intimate, one-to-one contact between the parent and any individual child. Consequently, children turn to each other for what they cannot get from their parents. The reduced parent–child contact encourages individual children to adopt specialized roles to gain recognition in the family. Age differences between siblings affect the childhood environment but to a lesser extent than does the gender of the sibling. The arrival of a sibling is difficult for toddlers and preschool children, especially between the ages of 2 and 3 years. At this age, they are still very attached to their parents and do not understand the concept of sharing. An older child is able to understand the situation and is less likely to see the newcomer as a threat, although the child does feel the loss of the only-child status (Coehlo, Kaakinen, Hanson, and others, 2009). In general, the narrower the spacing between siblings, the more the children influence one another, especially in emotional characteristics. The wider the spacing, the greater the influence of the parents. Traditionally, sibling relationships were viewed from a Freudian perspective that emphasized the concept of sibling rivalry. Researchers have viewed siblings through developmental or ecologic frameworks that focus on interactions within family systems (Friedman, Bowden, and Jones, 2003). The results of these broader perspectives provide a picture of rich and varied sibling interactions (Fig. 3-3).

Family Influences on Child Health Promotion

General Concepts

Definition of Family

Family Theories

ASSUMPTIONS

STRENGTHS

LIMITATIONS

APPLICATIONS

Family Systems Theory

A change in any one part of a family system affects all other parts of the family system (circular causality).

Family systems are characterized by periods of rapid growth and change and periods of relative stability.

Both too little change and too much change are dysfunctional for the family system; therefore, a balance between morphogenesis (change) and morphostasis (no change) is necessary.

Family systems can initiate change, as well as react to it.

Applicable for family in normal everyday life, as well as for family dysfunction and pathology

Useful for families of varying structure and in various stages of the life cycle

More difficult to determine cause-and-effect relationships because of circular causality

Mate selection, courtship processes, family communication, boundary maintenance, power and control within family, parent–child relationships, teenage pregnancy and parenthood

Family Stress Theory

Stress is an inevitable part of family life, and any event, even if positive, can be stressful for the family.

Family encounters both normative expected stressors and unexpected situational stressors over its life cycle.

Stress has a cumulative effect on family.

Families cope with and respond to stressors with a wide range of responses and effectiveness.

Potential to explain and predict family behavior in response to stressors and to develop effective interventions to promote family adaptation

Focuses on positive contribution of resources, coping, and social support to adaptive outcomes

Can be used by many disciplines in the health field

Relationships among all variables in the framework not yet adequately described

Not yet known if certain combinations of resources and coping strategies are applicable to all stressful events

Transition to parenthood and other normative transitions, single-parent families, families experiencing work-related stressors (dual-earner family, unemployment), acute or chronic childhood illness or disability, infertility, death of a child, divorce, teenage pregnancy and parenthood

Developmental Theory

Families develop and change over time in similar and consistent ways.

Family and its members must perform certain time-specific tasks set by themselves and by persons in the broader society.

Family role performance at one stage of family life cycle influences family’s behavioral options at next stage.

Family tends to be in stage of disequilibrium when entering a new life-cycle stage and strives toward homeostasis within stages.

Provides a dynamic, rather than static, view of the family

Addresses both changes within the family and changes in the family as a social system over its life history

Anticipates potential stressors that normally accompany transitions to various stages and when problems may peak because of lack of resources

Traditional model more easily applied to two-parent families with children

Use of age of oldest child and marital duration as marker of stage transition sometimes problematic (e.g., in stepfamilies, single-parent families)

Anticipatory guidance, educational strategies, and developing or strengthening family resources for management of transition to parenthood; family adjustment to children entering school, becoming adolescents, leaving home; management of “empty nest” years and retirement

Family Systems Theory

Family Stress Theory

Developmental Theory

Family Nursing Interventions

Family Structure and Function

Family Structure

Extended Family

Single-Parent Family

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Families

Family Strengths and Functioning Style

![]() Family function refers to the interactions of family members, especially the quality of those relationships and interactions (Bomar, 2004). Researchers are interested in family characteristics that help families function effectively. Knowledge of these factors guides the nurse throughout the nursing process and helps the nurse to predict ways that families may cope and respond to a stressful event, provide individualized support that builds on family strengths and unique functioning style, and assist family members in obtaining resources.

Family function refers to the interactions of family members, especially the quality of those relationships and interactions (Bomar, 2004). Researchers are interested in family characteristics that help families function effectively. Knowledge of these factors guides the nurse throughout the nursing process and helps the nurse to predict ways that families may cope and respond to a stressful event, provide individualized support that builds on family strengths and unique functioning style, and assist family members in obtaining resources.

Family Roles and Relationships

Parental Roles

Role Learning

Family Size and Configuration

Sibling Interactions

Spacing of Children

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Family Influences on Child Health Promotion

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access