Family Development and Family Nursing Assessment

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Explain the multiple ways public health nurses work with families and communities.

2. Identify barriers to family nursing.

3. Describe family function and structure.

4. Describe family demographic trends and demographic changes that affect the health of families.

6. Assess family needs to develop family action plans.

Key Terms

bioecological systems theory, p. 611

chronosystems, p. 612

cohabitation, p. 604

dysfunctional families, p. 606

ecomap, p. 614

exosystems, p. 611

family, p. 601

family cohesion, p. 607

family demographics, p. 604

family developmental and life cycle theory, p. 610

family flexibility, p. 607

family functions, p. 602

family health, p. 606

family nursing, p. 600

family nursing assessment, p. 607

family nursing theory, p. 609

family policy, p. 619

family structure, p. 603

family systems theory, p. 609

functional health literacy, p. 615

genogram, p. 614

macrosystems, p. 611

mesosystems, p. 611

microsystems, p. 611

social policy, p. 619

—See Glossary for definitions

Joanna Rowe Kaakinen, PhD, RN

Joanna Rowe Kaakinen, PhD, RN

Dr. Joanna Rowe Kaakinen has been a family nurse scholar for the last 20 years. She has written extensively about family nursing. She is a reviewer for the Journal of Family Nursing, the Journal of Family Relations, a member of the International Association of Family Nurses, and a member of the National Council of Family Relations. She has presented nationally and internationally on family nursing. Dr. Kaakinen is a Professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Portland in Portland, Oregon, where she teaches undergraduate and graduate family nursing courses.

Linda K. Birenbaum, PhD, RN

Linda K. Birenbaum, PhD, RN

Dr. Linda K. Birenbaum has been practicing and teaching family nursing for over 30 years since she first developed a family nursing theory course at Oregon Health Sciences University. Dr. Birenbaum has presented nationally and internationally on families with cancer. She was a professor at the University of Portland and taught undergraduate and graduate students community health nursing. Dr. Birenbaum currently is the Public Health Program Supervisor for Washington County Health and Human Services Public Health Department in Hillsboro, Oregon, where she manages three public health clinics providing services in family planning, sexually transmitted infections, immunizations, and prophylaxis for latent tuberculosis.

The health of communities is directly related to the health of the families (ANA, 2007; APHA, 2010; Eddy and Doutrich, 2010). Public health nurses must have skills to move competently between working with individual families, bridge relationships between families and the community, and advocate for family and community legislation and influence policies that promote and protect the health of populations. Therefore, public health nurses must integrate knowledge and practice of family nursing and community health nursing (APHA, 2010) in meeting the needs of families.

Family nursing is a philosophy and a science that is based on the following assumptions: health and illness are family events; what affects one family member affects the whole family; and health care practices, decisions, and behaviors are made within the context of the family (Kaakinen, Hanson, and Denham, 2010).

The definition of community health nursing practice used in this book states that it is a “synthesis of nursing theory and public health theory applied to promoting, preserving and maintaining the health of populations through the delivery of personal health care services to individuals, families, and groups. The focus of practice is the health of individuals, families and groups and the effect of their health status on the health of the community as a whole” (refer to Chapter 1).

Community health nurses use the core competencies for public health professionals (PHF, 2009) and the core public health functions of assessment, assurance, and policy development to promote the interconnectedness of individual health with the health of families and communities (Eddy and Doutrich, 2010). The Linking Content to Practice box shows the applications of public health nursing practice from a family perspective. The Healthy People 2020 box highlights new objectives proposed for the upcoming Healthy People 2020 initiatives. Community health nurses who practice with a family nursing philosophy and theory base will improve the health of families, their members, and the community.

Challenges for Nurses Working with Families in the Community

Numerous challenges exist that affect the practice of family nursing in a community setting. Many of the following challenges have been recognized in the family nursing literature for a long time, yet they persist in the current health care system. One role for the community health nurse would be to advocate that the following challenges be addressed in federal and state health care policies and programs.

Definition of Family

Now more than ever, the definition of family is being challenged. There is still no universally agreed upon definition of family (Kaakinen, Hanson, and Denham, 2010). Community health nurses and family nurses struggle on a daily basis with the conflict between the narrow traditional legal definition of family used in the health care system and by social policy makers and the broader term used by the family. Family, as defined and implemented in the health care system, has traditionally been based on using the legal notions of relationships such as biological/genetic blood ties, and contractual relationships such as adoption, guardianship, or marriage. However, the family system and family nurses use the following broader definition of family: Family refers to two or more individuals who depend on one another for emotional, physical, and/or financial support. The members of the family are self-defined” (Hanson, 2005).

Today more than ever, nurses need to adopt the open definition described above because the families they work with have a wide variety of family structures. Nurses who work with the people in the individual’s every day world have a higher likelihood of helping them to achieve better health outcomes.

Communication Difficulties

A common pitfall of the home health care system is the lack of communication and information in the transfer of clients between agencies that often occurs in interventions and health outcomes (Daily and Newfield, 2005) that frequently result in hospital admission or readmission. Nationally, the number of home health care clients who were admitted to the hospital between 2002 and 2006 was 28.3% (AHCRQ, 2008). The majority of these hospital admissions in home health care clients occurred within 7 days of admission to the home health agency (Vasquez, 2008). Approximately 18% of all Medicare hospitalizations result in readmissions within 30 days of discharge (Hackbarth, 2009). These hospital readmissions accounted for $15 billon, $12 billion of which was estimated to be preventable (Hackbarth, 2009).

In addition to a lack of communication between health care systems, there are communication issues between health care providers within the community agencies, such as incomplete or missing documentation that result from rushed assessments. Rushed procedures and failure to follow the plan of action and standards of care are known causes of hospital readmissions (Vasquez, 2008). It is crucial that home health care staff have current updates on evidence-based practice, standards of care (Hogue and Fairnot, 2006), and interventions to ensure quality health outcomes. Community health nurses have a significant role in working with multiple health care systems to improve communication and design protocols that are evidence-based to improve the quality of care and the health of the home health population (Ventura et al, 2010).

Nurses must develop and hone excellent negotiation skills because they spend a significant amount of time arranging for limited services for their underinsured and uninsured clients and families. In working with families, communication and teaching would be more effective if hours of service matched the times of day when family members, specifically the family care provider, can attend appointments. Bringing a companion to office visits benefits communication (Wolff et al, 2009; Wolff and Roter, 2008) enhances shared decision making (Clayman et al, 2005) and improves the sharing of information (Eggly et al, 2006). Involving family in the care of the client improves self management of health care, results in fewer medication errors (Kinnersley et al, 2007; Wolff et al, 2009), and improves health outcomes (Weinberg et al, 2007).

Uninsured, Underinsured, and Limited Services

Nurses must be adept at working among health care systems to find resources and services for the large population of uninsured clients and families. As of 2008, there were 46.6 million Americans without health insurance (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). Although the number of uninsured children is the lowest since 1987, the fastest growing group of uninsured is young adults (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). In addition, for those who have health care insurance, these companies traditionally base reimbursement and coverage on the individual’s disease or health problem and not the family unit or for informal family caregiving (Kaakinen, Hanson, and Denham, 2010).

The lack of insurance makes finding adequate services for clients and families difficult. In some areas federal and state funding for care in health clinics is free or available for a minimal fee. However, because the number of primary health care clinics is limited, care is provided on a lottery based solely on the number of volunteer health care providers working that day in the clinic. Many clinics are program based, such as family planning clinics, sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics, and immunizations clinics. Thus, it is difficult to meet the needs of the uninsured or underinsured populations.

These challenges are pervasive and serious. Nurses help clients and families negotiate and maneuver through the health care system. They must work closely with the family to remove barriers and provide services and resources that enhance the families’ abilities to provide quality care to family members. To successfully address these challenges, the community health nurses must integrate principles of family nursing with those of community/public health (see Evidence-Based Practice and Levels of Prevention boxes).

Family Functions and Structures

Knowledge of family functions and structures is essential for understanding how families influence health, illness, and well-being. Nurses who understand family functions and structures can use this knowledge to empower families through evidence-based interventions.

Family functions are the ways in which families meet the needs of (a) each family member, (b) the family as a whole, and (c) their relationship to society. Throughout history, the following functions have been performed by families (Kaakinen, Hanson, and Denham, 2010):

Family structure refers to the characteristics and demographics (e.g., sex, age, number) of individual members who make up family units. More specifically, the structure of a family defines the roles and the positions of family members (Box 27-1).

Family structures have changed over time to meet the needs of the family and society. The great speed at which changes in family structure, values, and relationships are occurring makes working with families at the beginning of the twenty-first century exciting and challenging. According to Kaakinen, Hanson, and Denham (2010, p 22), the following aspects need to be addressed when determining the family structure:

1. The individuals that compose the family

2. The relationships between them

3. The interactions between the family members

As social norms have become more tolerant of a range of choices in relation to managing one’s life, there is no longer a general consensus that the traditional nuclear family model, consisting of father, mother, and children, is the “best” model. There is no “typical” family model or family structure. For example, the single-mother household may be represented by the unmarried teenage mother with an infant (unplanned pregnancy), the divorced mother with one or more children, or the career-oriented woman in her late 30s who elects to have a baby and remain single.

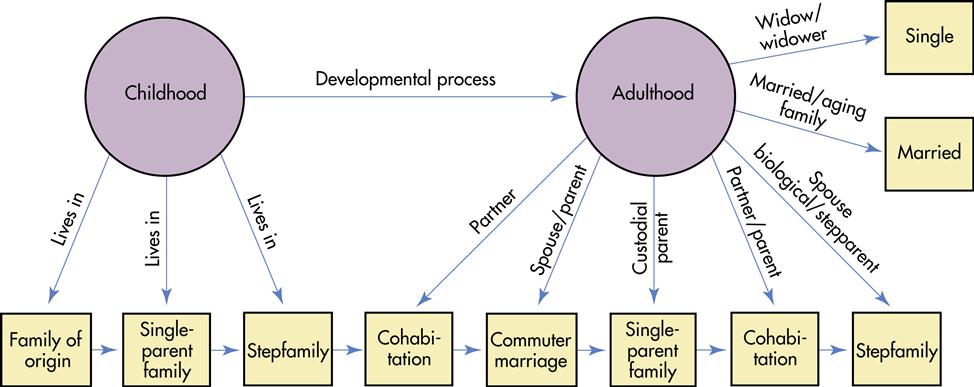

The family structure changes and modifies over time. An individual may participate in a number of family life experiences over a lifetime (Figure 27-1). For example, a child may spend the early, formative years in the family of origin (mother, father, siblings); experience some years in a single-parent family because of divorce; and participate in a stepfamily relationship when the single parent who has custody remarries.

This same child as an adult may experience several additional family types: cohabitation while completing a desired education, and then a commuter marriage while developing a career. As an adult, the individual may divorce and become a custodial parent. The adult may eventually cohabitate with another partner and finally marry a different partner who also has children. As couples age, they have to address issues of the aging family, and subsequently the woman may become an older single widow. Thus, nurses work with various families representing different structures and living arrangements.

Prospects for families in the twenty-first century are numerous. New family structures that are currently experimental will emerge as everyday “natural” families (e.g., families in which the members are not related by blood or marriage, but who provide the services, caring, love, intimacy, and interaction needed by all persons to experience a quality life).

At times it is helpful to understand families through a narrow framework of family function and structure. However, a family is a system within itself as well as the basic unit of a society. Some would argue that the traditional concept of family is disintegrating based on how the structure and functions of the family have changed over time. On the other side of that debate, families change in response to the societal changes and are ever evolving and thriving as they seek different ways of interconnectedness (Kaakinen, Hanson, and Denham, 2010).

Family Demographics

Historically, family demographics can be analyzed by looking at data about the families and household structures and the events that alter these structures. Nurses draw on family demographic data to forecast and predict family community needs, such as family developmental changes, stresses, and ethnic issues affecting family health, as they formulate possible solutions to identified family community problems. In this chapter, family demographic trends valuable to community health nurses are presented.

In 2007 in the United States, there were over 11.2 million households with 67% being family households and the remaining 33% being non-family households. Family households include a householder and at least one other member related by birth, marriage, or adoption; whereas a non-family household is either a person living alone or a householder who shares the house only with non-relatives, such as boarders or roommates (Krieder and Elliot, 2007).

Family demographic trends have continued in the direction of fewer married couples with children households (currently 71% compared with 93% in 1970). Children living in single parent families have stabilized since 2002 at 9% (Krieder and Elliot, 2009). Large households (five people or more) have decreased to 10% compared with 21% in 1970; whereas the small households (one to two people) increased from 46% to 60% over this same time period (Krieder and Elliott, 2007). The average household size remains at 2.6, but the average household has been affected by changes in us demographics (Krieder and Elliot, 2009; Grieco, 2007). Immigration and modest differences in natural increases have resulted in an increased racial and ethnic diversity, which is reflected in the white, non-Hispanic population declining 17% to 66% of the total population in 2007 (Grieco, 2010). Of the non-family households, 31 million were individuals living alone; 35% of the non-family households are 65 years of age or older.

Marriage and Cohabitation

Marriage, although still a popular American ideal, has assumed a forerunner: cohabitation. Cohabitation is a couple living together who are having a sexual relationship without being married. The probability that Americans will marry by age 40 is over 80% (Goodwin, McGill, and Chandra, 2009); however, cohabitation has become commonplace with a majority of young people projected to cohabitate at least once (Bumpass and Lu, 2000). Currently cohabitation rates are reported to be about 9% for men and women between the ages of 15 and 44 (Goodwin, Mosher, and Chandra, 2010).

Casper, Hagga, and Jayasundera (2010) suggest that people cohabitate for three reasons: some cohabitants would marry but do not for economic reasons; others seek a more equalitarian relationship; and others use cohabitation as a trial period to negotiate and assess whether to marry. Younger cohabitants are more likely to view their relationship as a prelude to marriage (King and Scott, 2005). This view is common, with a 65% chance of cohabitation transitioning to marriage within the first 5 years (Goodwin, Mosher, and Chandra, 2010). Phillips and Sweeney (2005) suggest that there is an ethnic factor in the meaning of cohabitation, with whites viewing cohabitation as a trial marriage and African Americans and Hispanic Americans viewing cohabitation as a substitute for marriage. In 2000 Seltzer suggested that, with the aging of the population, cohabitation may be of increasing importance among older persons. In 2005 King and Scott found that older adults enjoy relationships of higher quality and perceived stability despite having fewer plans to marry and are more likely than younger cohabitants to view their relationship as an alternative to marriage.

Different factors were associated with duration of marriage and cohabitation. Duration of marriage was associated with two factors: age of first marriage and timing of first child. Marriage at a younger age had a lower probability of the marriage lasting 10 years. Women who gave birth 8 months or more after the marriage began compared with women who had no first birth during the marriage had a 79% chance versus a 34% chance of the marriage lasting 10 years. Education was a factor in both men and women’s duration of cohabitation, with lower education being associated with longer cohabitation (Goodwin, McGill, and Chandra, 2010).

As cohabitation increases, ensuring sexually transmitted disease (STD) reduction and family planning services becomes essential. The most frequently reported infectious disease in the United States is chlamydia (CDC, 2010). In 2008 more than 1.2 million cases of chlamydia were reported. Women between the ages of 15 and 19 years of age and minority women are at the highest risk (CDC, 2010). Untreated chlamydia can cause severe and costly reproductive health problems. A model collaborative program is the Region X Infertility Prevention Project (2000), which aims to control chlamydia through collaborative efforts of STD and family planning providers and public health laboratories. A comprehensive approach to STD prevention that includes screening, treatment of infected partners, and behavioral interventions with a focus on reducing racial disparities is an important aspect of providing community health (CDC, 2010). See the Healthy People 2020 boxes on Family Planning and Sexually Transmitted Diseases.

Effects of Cohabitation on Children

Most children are born into families with married couples (64.5%), but 28.4% are born to mothers who had never married, and the remaining 7% are born to mothers who were divorced, separated, or widowed (Dye, 2008a). Since “never married” has the second highest ranking, attempts have been made to examine the effects of cohabitation on children. Poverty, income expenditures, and maternal parenting have been examined. DeLeire and Kalil (2005) found relatively high rates of poverty in cohabitating families with children compared with the national average (18.2%-22.4%, compared with 12.1% overall and 5.3% among married couples). They also found that cohabitating-parent families spend a greater share of their budgets on alcohol and tobacco than do married, divorced, and never-married single-parent families (DeLeire and Kalil, 2005). Nurses must ensure that these families have access to health insurance such as the Medicaid S-CHIP program. Teaching cohabitating families with children about the implications of second-hand smoke becomes a priority, since these children are at risk for health problems such as increased lower respiratory tract infections and asthma. Because poverty rates are higher, assisting these families in gaining access to resources such as food stamps and budget management skills is the work of nurses in the community. In 2001, Thomson et al found that although mothers yell and spank or hit their children less when cohabitating or remarrying, they provide less supervision. Spending more on alcohol and providing less child supervision place these children at risk for abuse or neglect, so nurses need to be vigilant in assessing these children and their families to prevent such unhealthy environments. These children are further endangered by the short-lived duration of cohabitation (DeLeire and Kalil, 2005).

Additional Trends in Marriage

Two additional trends in marriage are worth noting: increased age for first marriage and increased number of interracial marriages. The mother’s age at first birth has increased by 3.6 years between 1970 and 2006, making the average age 25 rather than 21.4 (Mathews and Hamilton, 2009). This may be influenced by educational attainment. Although men have a higher rate of attaining college degrees than women, that number is narrowing as data on younger cohorts show higher attainment for women than men, suggesting that the majority of people with college degrees may be women in the future (Crissey, 2009).

Later marriages can lead to older women becoming pregnant along with all the joys and complications attributed to these pregnancies in later life, such as infertility, STDs, and an increase in all obstetrical complications. Interracial marriage is another growing phenomenon in the United States. Lee and Edmonston (2005) report that interracial marriages increased from less than 1% of all married couples in 1970 to more than 5% in 2000.

Since 1965 when the Immigration Act abolished the national origins quota, the United States has become more diversified. In 1960, 75% of foreign-born people living in the United States were born in Europe; by 2007, 80% of foreign-born were born either in Latin America or Asia (Grieco, 2010). The current emphasis in family demographics is the race or ethnicity of the American family, which has weighty implications for community health nursing (Crissey, 2009; Davis and Bauman, 2009; Dye, 2008a,b). Of the 281.4 million counted in the 2000 Census, 75.1% were white, 12.1% were Black or African American, 0.9% were American Indian and Alaska Native, 3.6% were Asian, and 0.1% were Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander. The Hispanic population was 12.5%. For the first time, Hispanics outnumbered African Americans in this country; the Hispanic population reached 41.3 million people as of July 1, 2004 (Bernstein, 2005).

Race and ethnicity has implications for American women’s fertility, educational attainment, and participation in government assistance programs. Family Planning and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) are two federally funded public health programs that require community health nurses to understand the implications of race and ethnicity on public health services. For example, in some instances a woman attending a public health clinic for family planning services may be accompanied by her husband who is the only adult family member who speaks English. If adequate interpretative services are not available, the husband may attempt to complete the medical history form and it may or may not be accurate, thus impacting the services provided. This requires community health nurses being knowledgeable about the race and ethnic composition of their community and providing adequate staffing for the major languages spoken in that community.

Births

Fertility rates differ by race and ethnicity. Hispanic women have the highest fertility rates with 74 births per 1000; American Indian and Alaska Native women were next with 68 births per 1000, followed by African-American women with 58 births per 1000; Asian women had 54 births per 1000 and white non-Hispanic women had the lowest rates of 50 births per 1000 (Dye, 2008a). Foreign-born Hispanic women who were not citizens had statistically higher fertility rates than their native naturalized counterparts between 20 and 29 years of age.

Not all cultures value limiting the number of children in a family, and nurses may be challenged to understand these values and to provide services where the woman assumes the value of limiting the number of children where the husband does not. For example, a Hispanic woman comes to the public health clinic for family planning services. It is not uncommon for the husband to come in at the end of the week to pay for those services. If the wife is on birth control, such as Depo, but does not want her husband to know, itemizing services on the receipt would present a problem. The nurse needs to understand these changing values and facilitate the family planning services requested by the woman without violating her confidentiality.

Divorce or Dissolution of Cohabitation

Divorce can be said to be increasing, declining, or remaining stable, depending on the time referent. Divorce rates in the 1970s and into the mid-1980s climbed to 5.0 per 1000, but around 1985 through 2000 they began to decline to 4.0 per 1000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). In 2001 the median length of a marriage for divorcing couples was 8 years for men and women overall (Kreider, 2005). Lowenstein (2005) identified the following factors that lead to divorce: women’s independence in the marriage, money issues, poor education and social skills, inability to manage conflict, sexual incompatibility, alcohol and substance abuse, risk-taking behaviors, and religious issues. Lowenstein summarized the following effects on the divorced family:

• Diminishment of the father’s role in the family

• Negative impact on the children

• Emotional problems for a number of persons involved

The economic hardships of divorce and cohabitating dissolution are similar (Avellar and Smock, 2005). These economic hardships of cohabitating dissolution are unequally distributed, with white women faring better than African-American or Hispanic women (Avellar and Smock, 2005).

The characteristics of people who divorce vary by race, religion, and educational level. The divorce rate for African Americans is higher than for whites, Hispanic Americans, or Asian and Pacific Islander Americans (Kreider, 2005; Teachman, Tedrow, and Scanzioni, 2000). Protestants have a higher divorce rate than Catholics. Women and men with at least a bachelor’s degree are less likely to divorce than those who have a high school degree or less (Kreider, 2005). Phillips and Sweeney (2005) found that whites who cohabitated with their spouse before marriage were at a greater risk of divorce than African Americans or Hispanic Americans. Premarital conception was a risk factor for divorce in African Americans who cohabitated before marriage. Nativity (American born) was a risk factor for divorce in Mexican Americans who cohabitated before marriage.

Divorce and dissolution of cohabitation come to the attention of the nurse mostly with respect to the 40% of children projected to live in parent-cohabitating families before they reach adulthood. Since women are still the dominant custodial parent, the economic adverse effects they suffer are also experienced by the children. Nurses need to ensure that health care services are available for these families.

Remarriage

Until the 1970s, bereavement, the leading cause of remarriage, was replaced with divorce (Coleman, Ganong, and Fine, 2000). More than 50% of divorced people remarry (Kreider, 2005). Whereas gender was previously a leading factor in remarriage rates, the person who initiated the divorce has been found to be a more significant factor (Sweeney, 2002). That is, women who initiate divorce are more likely to remarry than women who were the non-initiators. The probability of remarriage for white women is 58%, for Hispanic women is 44%, and for African-American women is 32% (CDC, 2002).

For middle-aged families, this results in more blended families and issues of childcare. Although some persons remarry more than once, remarriages by adults more than 40 years of age may be more stable than first marriages (Coleman, Ganong, and Fine, 2000).

It is imperative that the nurse keep informed and up to date about demographic trends pertaining to families and all types of households. Such knowledge is essential so that nurses can identify high-risk populations, such as children living in poverty, children of working mothers who care for themselves (latchkey children), and older adult women living alone. Changing demographics have implications for planning health, developing community resources, and becoming politically active, so that scarce funds and resources can be made available for health services needed by the growing and diverse population. Demographic data are usually updated every 5 years. In 2010 a new census was taken of the U.S. population.

Family Health

The meaning of family health is not precise and lacks consensus, despite the increased focus on family health within the nursing profession. The term family health is often used interchangeably with the concepts of family functioning, healthy families, and familial health. Hanson (2005, p 7) defines family health as “a dynamic changing relative state of well-being which includes the biological, psychological, spiritual, sociological, and cultural factors of the family system.”

This holistic approach refers to individual members as well as the family unit as a whole entity and in turn the family within the community context. An individual’s health (the wellness and illness continuum) affects the functioning of the entire family, and in turn, the family’s functioning affects the health of individuals. Thus assessment of family health involves simultaneous assessment of individual family members, the family system as a whole, and the community in which the family is imbedded.

Health professionals have tended to classify clients and their families into two groups: healthy families and non-healthy families, or those in need of psychosocial evaluation and intervention. The term family health implies mental health rather than physical health. A popular term for non-healthy families is dysfunctional families, also called non-compliant, resistant, or unmotivated—phrases that label families who are not functioning well with each other or in the world.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree