Family Case Management

Claudia M. Smith*

Focus Questions

What is family case management?

What is the purpose of family assessment?

How does the nurse analyze family data?

What are family nursing diagnoses?

How are priorities determined in family nursing?

What principles will help the nurse and family develop an effective plan of care?

How do family style, family strengths, and family functioning influence care planning?

How do family–nurse interventions vary with different family needs?

What are the possible outcomes of the evaluation phase of the nursing process?

Key Terms

Eco-map

Family case management

Family functioning

Family map

Family needs

Family strengths

Family style

Formative evaluation

Genogram

Priorities

Social support

Summative evaluation

Targets of care

The betterment of human communities is the goal of community/public health nursing. To achieve this, community/public health nursing interventions may be directed to the community and its populations, community systems, and individuals/families within populations at risk (Minnesota Department of Health, 2001). Improving the health of families can improve the health of the community (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007; Quad Council, 2011). As part of their scope of practice, baccalaureate-prepared community/public health nurses are expected to be able to implement programs of care targeted toward families.

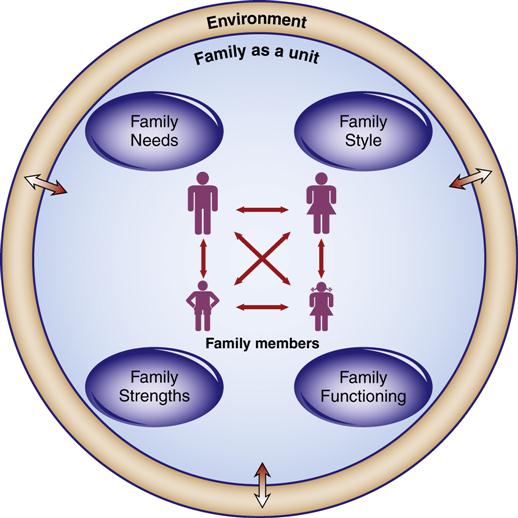

Family health nursing is the practice of nursing directed toward maximizing the health and well-being of all individuals within a family system. Two views of a family are incorporated: (1) family as the unit of care and (2) family as context for individuals and family subsystems. When working with families, the community/public health nurse’s goal is to promote optimal health for each member of the family and for the family as a unit. Bringing a family perspective to the arena in which the nurse will meet with the family will change the way the nurse practices. The nurse begins to consider more complex needs and more complex interactions as care is offered. The Family Needs Model of family health nursing introduced in Chapter 12 will be used as the guide in this text (Figure 13-1). Using the Family Needs Model, the community/public health nurse assesses and analyzes family needs, family style, family strengths, and family functioning.

• Identifying family needs allows the nurse to determine the areas in which the family needs help.

• Describing family strengths enables the nurse to suggest ways to build on the family competencies.

• Determining family functioning allows the nurse to set realistic goals with the family.

(See text for explanation.) (Copyright [1995]. Used with permission.)

As with all nursing practice, the practice of family health nursing builds on the foundation of the nursing process. Community/public health nurses assess, diagnose, plan, implement, and evaluate their nursing care for and with families.

For nurses who work with families, extra challenges are posed in the complexity and skill that are sometimes required to deal with these larger and more intensely connected groups of people. The nurse’s ability to establish a relationship that respects the family’s rights and strengths becomes more important than any other task. Trust, open communication, and acceptance of diverse family values are essential. Although the community/public health nurse has responsibilities to the community and wishes to affect the health of each family member and the family as a whole, she or he must always remember that the family is ultimately responsible for its actions. The nurse’s role is limited to that of a facilitator, educator, or advocate, except in the most extreme cases of personal safety or abuse. Success depends primarily not on what the nurse does but on her or his talent at empowering the family to act for itself.

Family case management

Case management of families seeks to “optimize the self-care capabilities” of families regarding their health and well-being (Minnesota Department of Health, 2001, p. 93). A public health nursing perspective for family case management includes outreach to find families in need, focus on prevention, and reliance on health teaching, counseling, and referral and follow-up with families (Minnesota Department of Health, 2001). Nurses consult with family members in problem solving, as well as coordinate services and resources on behalf of families. Public health nursing case management is “client-centered

and relationship-based” (Minnesota Department of Health, 2001, p. 100). Additionally, advocacy and collaboration within the community or community systems may emerge from the relationship(s) with families. Family case management in public health nursing is neither disease management nor benefits management for managed care or an insurance company. The above aspects of case management in community/public health nursing are considered best practices (Minnesota Department of Health, 2001) and are integrated with the nursing process (ANA, 2007).

Family assessment

As with all assessment, the nurse uses as many possible sources of data as is practical to help complete a comprehensive picture of the family and each member. Of course, before discussing a family or reviewing the family’ s records with a member of the health care team from another agency, the family’ s permission must be obtained. Sources of data can include, but should not be limited to, charts and written health records, biological data such as blood pressures or specimens, telephone calls and conversations with other health care team members, information from social service agencies involved with the family, and environmental and community information. However, the most accurate and complete information can be obtained only by observing and interviewing the family itself.

Interviewing families can be more difficult than interviewing an individual client and, for a nurse who is not familiar with this situation, a little frightening. After all, the family has been together for a long time and has a history together that gives strength and a collective power to even the most dysfunctional family. Interviewing families can also be a rich source of information and a path to establishing relationships that are fulfilling and meaningful for both the nurse and the family members.

Families may first be seen in the hospital, clinic, community setting, or in their own homes. Meeting families in their own environments is preferable because the nurse can observe firsthand the physical and environmental conditions, as well as the way family members interact with each other on their own turfs. Preparing for a home visit is discussed in Chapter 11. Ideally, the nurse will keep these principles in mind when planning the first meeting with the family.

The nurse should try to include as many family members as is possible in the interview. Each family will have a communicator (someone who tends to speak for the other members of the family) and usually a leader (someone who takes charge of family operations). Often, but not always, the communicator and the leader are the same person. Although you can work through this strength, be aware that, to be accurate, perceptions of the problem or concern and other data must be gathered from all persons. Being able to see the family together often gives the observer information about family interaction that is useful.

The goal of family assessment is to gather information that allows the nurse and family to identify family needs together and to plan care that will allow the family to work toward more optimal health for individual family members and for the family as a whole. Families can then be assessed on several levels: assessing individuals within the family, assessing interactions among subsystems, assessing the family as a unit, and assessing the family within the environment. A comprehensive family assessment should include information gathered about and from all of these levels. Data that are essential to collect include the following:

Assessing Individual Needs

Typically, one member of the family is identified as the client who is to be the recipient of nursing care. This client may have an identified health problem (e.g., a recent discharge from a hospital after a stroke, a communicable disease), a chronic illness that needs continued monitoring (e.g., diabetes), or a potential problem (e.g., a new mother who needs education about caring for her infant). Adequate identification and collection of information about the client’ s response to these actual or potential health problems is the first priority in family assessment.

However, many families will have more than one member with actual or potential health problems. Because family members are interconnected, the health of all members is a concern to the nurse. Depending on the mission and guidelines of the agency and the nurse’ s role, all family members are potential targets of individual assessment. For example, suppose the identified client is a 55-year-old man who has developed a foot ulcer. He may eventually need assistance with moving and transferring. What if the only other member of the family, his wife, has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and is unable to help? Family health is interconnected because members share their environment and depend on each other.

Individual assessment will vary with the age, gender, and particular health status of each person. Included in the assessment may be comprehensive health or physical assessment, assessment of developmental level, mental status assessment, focused information about specific health problems such as incontinence or decubiti, or assessment of coping and adaptation. Some specific individual assessments are outlined in Box 13-1.

All family members can benefit from health promotion and disease or injury prevention. Community/public health nurses need to assess the history of immunizations and screening tests for each family member. By comparing this information with recommended schedules for immunizations (see Chapter 8) and screening tests (see Chapter 19), nurses can identify the immunizations and screening tests that each family member needs.

Assessing Family Subsystems

Families interact in small interpersonal groups. Understanding the interactions and functioning of these dyads and triangles is important to understanding the functioning of the family and ascertaining available support. Subsystems such as the parent–child subsystem, the marital pair, and the sibling subsystem should always be assessed. Other, less obvious, subsystems might be grandparent–grandchild, foster parent–child, or parents–young married couple. Tools that can be used include maps of social interaction, tools that assess the health of developmental bonds such as mother–child interaction, and tools that target problems in dyads, such as elder abuse screening tools. Examples of these assessments are presented in Box 13-1.

Assessing the Family as a Unit

Although assessing families in smaller segments is helpful, these assessments do not capture the nature of the family as a whole. Families have unique identities that cannot be understood when thinking about only the segments. Parameters that are often assessed include family processes, roles, communication, division of labor, decision making, boundaries, styles of problem solving, coping abilities, and health-promotion practices. Some specific tools are outlined in Box 13-1, and some of the more widely used family assessments are discussed in the following sections.

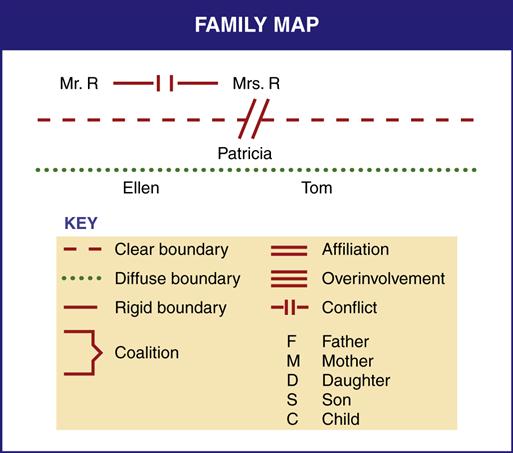

Family Maps

A family map is used to diagram spatial and relationship qualities of a family system. The tool originated with structural–functional family therapists (Minuchin & Fishman, 1981). These researchers began observing the structure and interaction of families in therapeutic situations and mapping families to understand their hierarchies, roles, and power. After an interview in which the family is observed in an interactive situation, a map is drawn that details the subsystems, the boundaries between subsystems, and interactive patterns, such as coalitions, conflict, and avoidance.

A healthy family will demonstrate age-appropriate subsystems. Power will reside with parents, and children will have the nurturant guidance they need to grow. Spousal subsystems will have a clear identity. Boundaries between subsystems will be clear and permeable. Diffuse boundaries allow too much confusion because members move back and forth without clear definition of roles. Rigid boundaries serve to shut off necessary interaction and discourage flexibility and adaptiveness. Interactive patterns tend to repeat themselves and provide information about who will communicate and in what way the communication may occur. Symbols for the maps are shown in Figure 13-2.

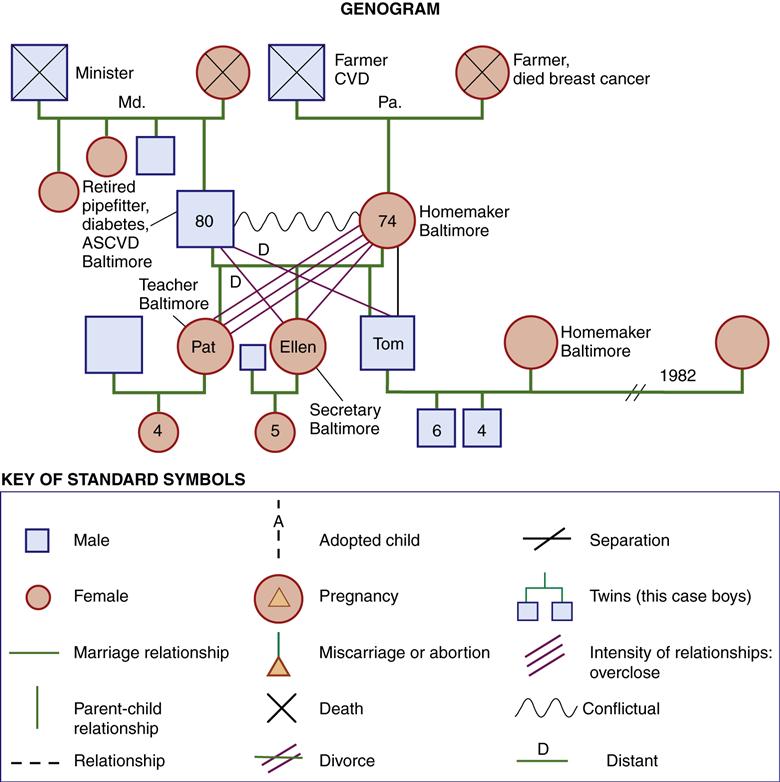

Genograms

A genogram is a format for drawing a family tree that records information about family members and their relationships for at least three generations (Cain, 1981; McGoldrick, Shellenberger, & Petry, 2008). Genograms help community/public health nurses remember the family members, patterns, and significant events that are important in the family’s care. The picture of the family that is presented in the genogram helps the observer think about the family systemically and over time. Occasionally, when a larger picture is presented, connections between events and relationships become clearer and are viewed in a more objective way.

Genograms serve several other functions. The process of collecting and recording information for constructing a genogram serves as a way for the interviewer and family to connect in a personal but emotionally safe way. The genogram also provides the interviewer with information about how the members of the family think about family problems and interact with other members. Recording information on a genogram can serve to detoxify issues or reduce anxiety about the family problem. During the process, family members are required to think, organize, and present facts. The nurse helps the family normalize and reframe problems so that they are viewed in a larger context. This type of interaction can help family members step back and think about an issue in a calm way.

Typically, the genogram is constructed in the first or an early session and revised as new information becomes available. Genogram construction may be divided into three parts:

To map the family structure, a diagram of family members in each generation is drawn using horizontal and vertical lines. Symbols used to represent pregnancies, miscarriages, marriages, and deaths are presented in Figure 13-3. Male family members are placed on the left of the horizontal line; female members on the right. Birth order is represented by placing the oldest sibling on the far left and progressing toward the right. In the case of multiple marriages, the earliest is placed on the left and the most recent on the right.

Family information that is usually helpful includes ages, dates of birth and death, geographical location, occupation, and educational level. Critical family events and transitions such as moves, marriages, divorces, losses, and successes are recorded. Family members’ physical, emotional, or social problems or illnesses are identified. A genogram facilitates discussion of the role of heredity and recommendations for genetic screening (De Sevo, 2010), as well as prevention of illnesses common in the family. A chronology, or time line, of family events is often useful to help people see relationships between events and behavior changes.

Observing and describing family relationships is the stage that is the most crucial and often the most helpful to the family but is often ignored. Relationship patterns can be quite complex and are inferred from observations and from family members’ comments and analyses. The nurse should identify patterns of closeness, conflict, and distance. When relationships are too close, this intensity is also noted. Some symbols that are used to represent relationships are presented in Figure 13-3. Triangles are present in every family (see Chapter 12). Attempting to map the primary or most influential triangles in the family is a part of describing the family relationships.

The genogram is an assessment tool that can be useful throughout the contact with the family. At some point, the genogram may also be used as a therapeutic tool whereby information is interpreted and used to help individuals define the way they would like to operate within the group. Although the nurse may yield to thinking that she or he knows what the family should do, interpretations that come from family members themselves are usually more accurate and useful for change.

Family Cultural Assessment

At this point, competence in family cultural assessment is also required. When working with diversity in families, the nurse needs to develop an awareness of her or his own existence, thoughts, and environment without letting it have undue influence on others. The nurse should be able to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the family’ s culture and also respect for cultural differences. If language is a barrier, interpreters can be used, but time must be allowed for translation, and using children as interpreters should be avoided. Cultural norms about personal space, touch, and eye contact vary; thus, the nurse needs to be aware of nonverbal behavior and adjust it, as necessary. Box 13-2 presents Purnell and Paulanka’s model (2008) of cultural competence with hints for areas of family life to assess. See Table 10-4 for a more detailed guide to family cultural assessment.

Assessing the Family within the Environment

The family is a group of interacting people who also live within an external physical and interpersonal environment. Data about the family’ s physical environment, such as the presence of accident hazards, window screens, plumbing, and cooking facilities, help the nurse (1) plan care that matches or supplements family resources and (2) identify potential health problems. Some physical conditions that should be assessed are presented in Box 13-1. Home Observation for Measurement Environment (HOME), an observation tool developed to assess the potential of the environment for development of children from birth to 6 years of age, is an example of a tool that can be used to collect data about the physical environment (Caldwell, 1976) (see also Chapter 9).

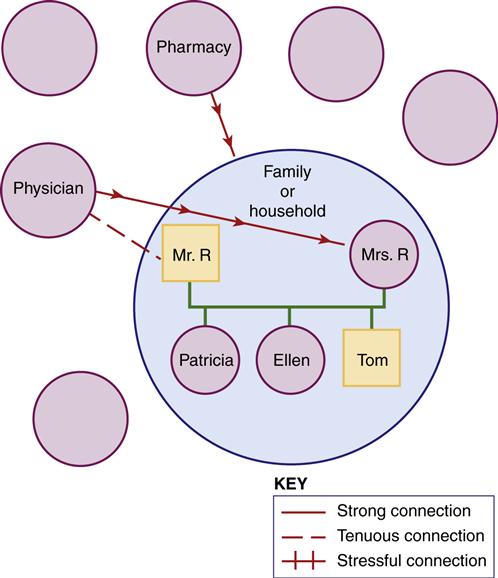

Community resources and facilities that are available to the family should also be noted. However, some families can live within a fairly resource-rich environment and be unable to maintain the connections that are needed to tap these resources. An eco-map (Hartman, 1978) is a tool that can help the nurse and the family discover patterns of energy flow into and out of the family. The family’ s relationships with significant community resources, activities, and agencies are diagrammed. Are these connections strong, tenuous, or stressful? The diagram illustrates the amount of energy that a family uses to maintain its system and what support is available. After the nurse helps the family prepare the diagram, the eco-map helps family members visualize how relationships with external systems are affecting their state of well-being. An eco-map is presented in Figure 13-4.

Directions: Fill in connections where they exist. Indicate their nature by descriptive words or different lines. Draw arrows along lines to signify flow of energy and resources. Identify significant people. Fill in empty circles, as needed. (Adapted from Hartman, S. [1978]. Diagrammatic assessment of family relationships. Social Casework, 59, 470. Reprinted with permission from Families in Society [http://www.familiesinsociety.org], published by the Alliance for Children and Families.)

Other aspects of the environment, such as chemical exposure, air quality, and danger in neighborhoods with a high level of criminal activity, also affect families. Krieger and colleagues (2005) described low-income families that are at risk for asthma related to the high incidence of indoor asthma triggers in their environment. Lead exposure for young children in older buildings is another example of risk. Musculoskeletal injuries, accidents, exposures to radiation and carcinogens, and sound damage to hearing are examples of danger in the workplace. An example of a tool to assess a family’ s occupational and environmental history is the Occupational and Environmental Health History (Wiley, 1996) in Box 13-3. Also see Box 9-2 for another tool.

Analyzing family data

The different types of assessments discussed in the preceding section provide not only a comprehensive assessment but also a massive amount of data. Family assessments can be complex and confusing if these data are not sorted and analyzed in some way. What does this information mean, and in what way can it be used to help the nurse and family plan their work together? The information must be integrated and analyzed before decisions about the plan of care can be made. Once the information is summarized and targets of care are identified, the process of intervention is clearer for the nurse and the family. Neglecting to accomplish this task carefully can lead to feelings of being overwhelmed or to nonfocused, constantly changing interventions. The following steps can be used to help organize these data:

• Determining family needs or areas of concern

• Determining family strengths

• Determining family functioning

• Determining nursing’s contribution

Determining Family Needs

When looking at family needs, the nurse is asking the following questions:

“What?”

“In what areas does the family need help?”

“What concerns do the nurse and family want to explore?”

These needs are identified on multiple levels: needs of individual members, needs of family subgroups, needs of the family as a whole, and needs related to the family interacting with the environment. Nursing diagnoses can be developed that represent each of these areas. The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA International) has been identifying and listing diagnostic nomenclature since the early 1970s.These diagnoses are formulated to help nurses choose and focus nursing interventions by concentrating on client responses to health promotion and actual or potential health problems rather than on the disease process. Each diagnosis consists of two parts: (1) the unhealthy response and (2) an indication of the factors contributing to the response. Problems may be those that exist currently (actual) or may possibly exist in the future (potential), or the problems may relate to health promotion.

Nursing diagnoses for individual family members are identified just as they are when an individual is the sole target of care. Diagnoses that represent responses to health problems are organized according to patterns or clusters of behaviors such as sleep and rest, elimination, and activity and exercise (Newfield et al., 2007).

Interpersonal nursing diagnoses may include needs that represent the interaction of more than one person, for example, “Breast-Feeding: Ineffective,” or diagnoses that affect more than one person, for example, “Social Interaction: Impaired.” Examples of individual and interpersonal nursing diagnoses are presented in Box 13-4.

Family nursing diagnoses have also been identified by NANDA International (2009). The nomenclature used includes the following:

• Family Processes: Dysfunctional

• Family Processes: Interrupted

• Family Processes: Readiness for Enhanced

• Family Coping: Compromised or Disabled

The major defining characteristics that correspond to these diagnoses include most of the concepts discussed within the family chapters in this book and are presented in Box 13-5.

However, some authors find that the NANDA International family nursing diagnoses are not sufficiently specific. The Family Needs Model (Smith, 1985) suggests that five major areas exist in community health nursing in which families and nursing intersect (Box 13-6). This delineation may help the nurse identify more specific family needs. Families meeting normal growth and developmental challenges often benefit from health-promotion and illness-prevention education or supportive contact as family members master behaviors appropriate for their new stage of life.

Families coping with illness or loss not only need emotional support but also need concrete help such as direct care, education, and connection to services. Families dealing with external stressors such as natural disasters, unemployment, or societal violence benefit from emotional and physical support. During this time of crisis, the family may be strained and not as functional. However, a crisis period may also be a time for the family to grow and discover strength under stress.

Inadequate resources or support can be temporary or long term. For example, a family with several events happening at once (e.g., children in college, an illness, an aging parent) may find its usually sufficient resources inadequate. Other families deal with the chronic problem of poverty, lack of access to resources, and inadequate energy to maintain self-esteem and meet other persons’ emotional needs (see Chapter 14).

Families with disturbances in internal dynamics create stress from within. The unhealthy way in which they operate tends to provoke rather than mediate their stress. Of course, families can have combinations of these problems, or some of the problems may potentiate others. However, this framework covers most of the needs families will present in the community/public health setting.

Environmental problems for families are described in the Omaha System problem classification scheme (Martin, 2005). Problems with material resources and physical surroundings include income, sanitation, residence, and neighborhood and workplace safety, including environmental hazards (Table 13-1).

Table 13-1

Nursing Diagnoses for Environmental Problems

| Problem | Signs and Symptoms |

| Income | Low/no income, uninsured medical expenses, difficulty with money management, able to buy only necessities, difficulty buying necessities, other |

| Sanitation | Soiled living area, inadequate food storage/disposal, insects/rodents, foul odor, inadequate laundry facilities, allergens, infectious/contaminating agents, mold, excessive pets, other |

| Residence | Structurally unsound, inadequate heating/cooling, steep stairs, inadequate/obstructed exits/entries, cluttered living space, unsafe storage of dangerous objects/substances, unsafe mats/throw rugs, inadequate safety devices, presence of lead-based paint, unsafe gas/electric appliances, inadequate/crowded living space, homeless, other |

| Neighborhood and workplace safety | High crime rate, high pollution level, uncontrolled animals, physical hazards, unsafe play areas, other |

Adapted from Martin, K. (2005). The Omaha System: A key to practice, documentation and information management (2nd ed.). St. Louis: Saunders.

Family problems related to the social environment may occur in the areas of communication with community resources and social contact (Table 13-2). Each problem may have actual or potential impairments or opportunities for health promotion.

Table 13-2

Nursing Diagnoses Related to the Use of Social Resources

| Problem | Signs and Symptoms |

| Communication with community resources | Unfamiliarity with options/procedures for obtaining services, difficulty understanding roles/regulations of service providers, unable to communicate concerns to service provider, dissatisfaction with services, cultural or language barrier, inadequate/unavailable services, transportation barrier, other |

| Social contact | Limited social contact, uses health care provider for social contact, minimal outside stimulation/leisure time activities, other |

Adapted from Martin, K. (2005). The Omaha System: A key to practice, documentation and information management (2nd ed.). St. Louis: Saunders.

Different family needs require different intervention strategies from the nurse. Specific interventions for each of the five categories of family needs are discussed later in this chapter.

Determining Family Style

Most families have characteristic processes they use to meet challenges and deal with others. Identifying this style will help the nurse choose appropriate actions and ways of working with the families. Determining the family style helps the nurse answer the following questions:

“How?”

“How should I adjust my interpersonal interactions to match the family style?”

“How will the way the family typically acts affect planning and implementation of care with this family?”

“How will I even get in the door or get the family to accept my presence?”

“In what ways does the family usually act to process information, solve problems, and open or close itself to the environment?”

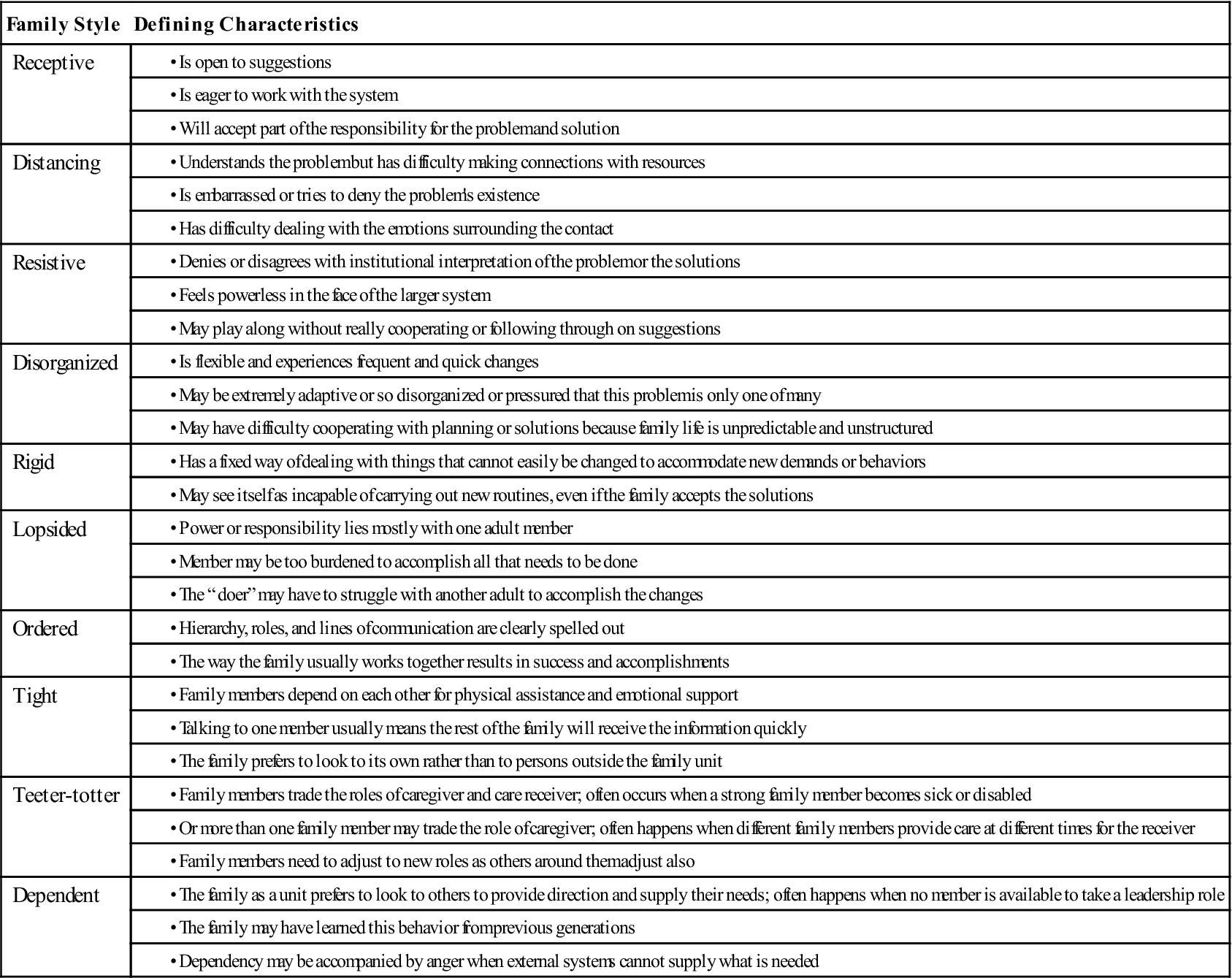

Family style usually has two components: (1) internal family interactions and (2) relationship to the outside world. These patterns remain fairly consistent over time. The styles describe family patterns of meeting challenges and dealing with others. Some families are organized within themselves and are receptive to interactions with a helper. Other families have more trouble with organization, are resistive, or are distant. Identifying this style will help the nurse choose appropriate actions and ways of working with the family. Information gained from tools that assess the family’ s coping ability, patterns of interaction, and use of support from others can be integrated to complete this analysis. Table 13-3 presents a format for thinking about family style.

Table 13-3

| Family Style | Defining Characteristics |

| Receptive | |

| Distancing | |

| Resistive | |

| Disorganized | |

| Rigid | |

| Lopsided | |

| Ordered | |

| Tight | |

| Teeter-totter | |

| Dependent | |

Developed by Marcia Cooley, PhD, RN.

Different family styles require different interactions from the nurse. The competent family health nurse will be able to adjust her or his own personal way of relating to others to match the family style. If a family is distant in the face of emotional and private events, moving in too quickly would make them retreat even more. Each nurse should examine personal ways of behaving and practice a flexible repertoire of interactions to be used when the family situation requires it. The principles for interacting with different family styles are presented in Table 13-4.

Table 13-4

Principles for Adjusting Interactions to Family Style

| Family Style | Principles for Interaction |

| Receptive | |

| Distancing | |

| Resistive | |

| Disorganized | |

| Rigid | |

| Lopsided | |

| Ordered | |

| Tight | |

| Teeter-totter | < div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|