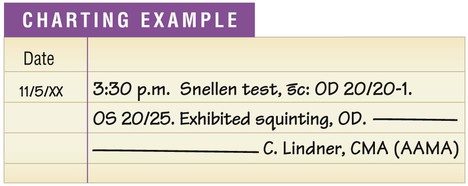

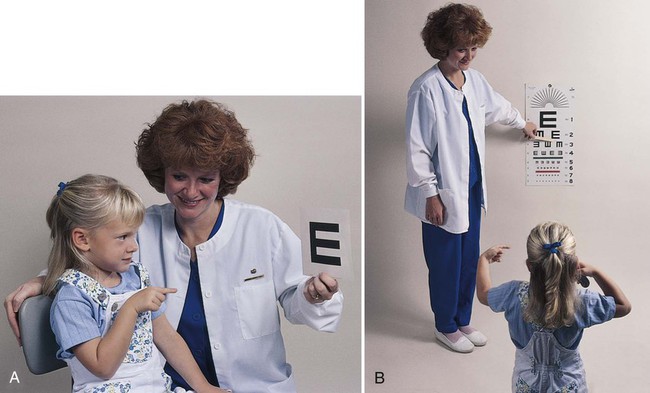

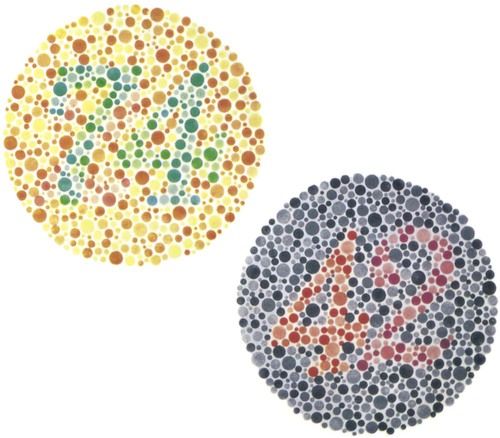

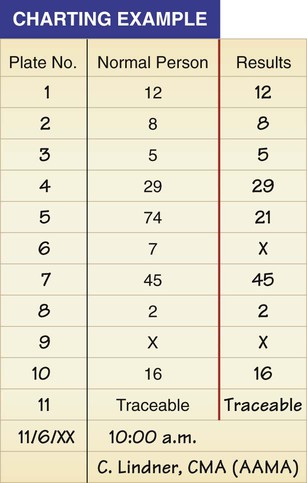

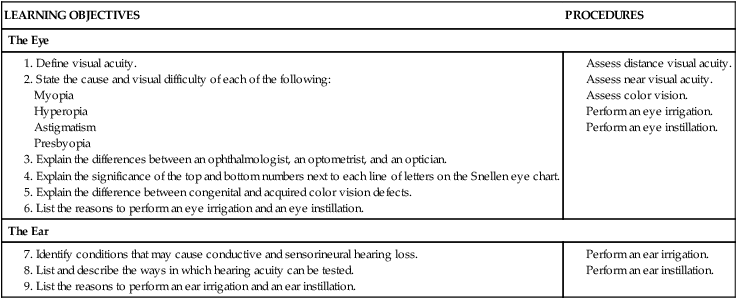

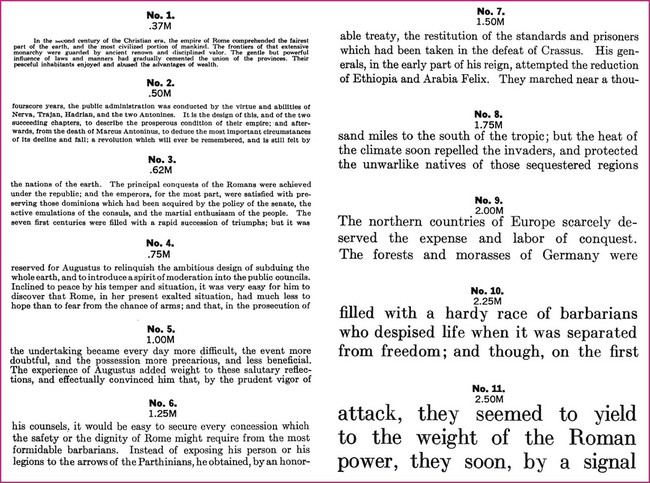

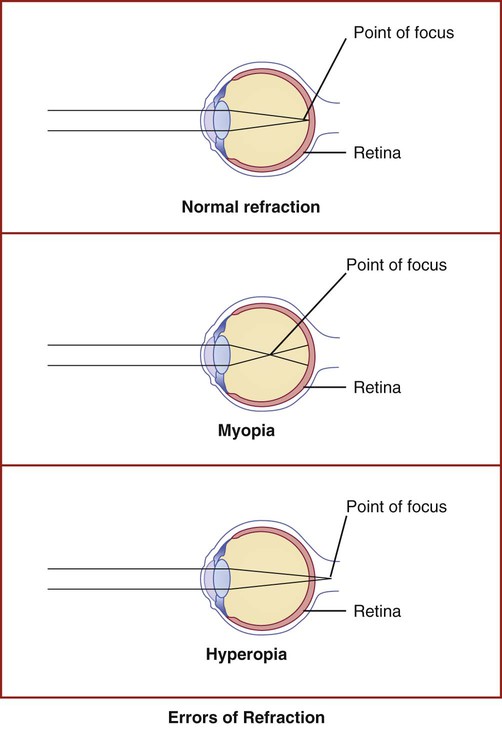

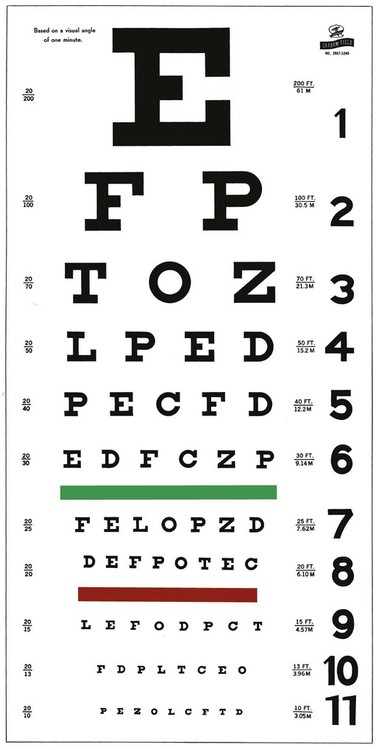

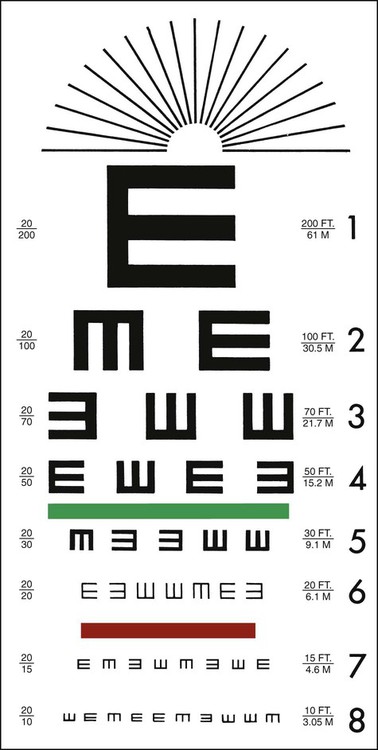

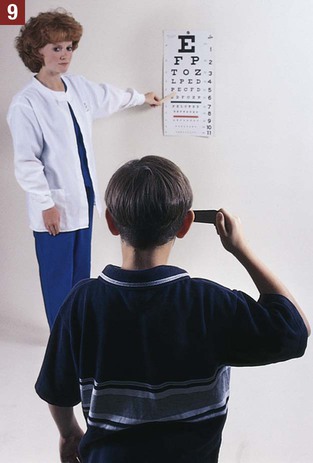

The medical assistant is responsible for performing a variety of assessments and procedures that involve the eye. An understanding of the structure and function of the eye is essential to mastering skills in these areas. Refer to Chapter 10 to review the structure and function of the eye. The medical assistant is responsible for performing or teaching the patient to perform eye irrigations and instillations. Irrigation is washing a body canal with a flowing solution. Instillation is dropping a liquid into a body cavity. Eye irrigations and instillations should be performed using the important principles of medical asepsis outlined in Chapter 17. Errors of refraction are the most common causes of defects in visual acuity (Figure 21-1). Refraction refers to the ability of the eye to bend the parallel light rays coming into it so that they can be focused on the retina. An error of refraction means that the light rays are not being refracted or bent properly and are not adequately focused on the retina. A defect in the shape of the eyeball can cause a refractive error. Errors of refraction can be improved with corrective lenses. Myopia can be diagnosed (in combination with other tests) by a distance visual acuity test. In the medical office, the Snellen eye chart is most often used. Two types of charts are commonly used. One type is used for school-age children and adults and consists of a chart of letters in decreasing sizes (Figure 21-2). The other type is used for preschool children, non–English-speaking people, and nonreaders; it is composed of the capital letter E in decreasing sizes and arranged in different directions (Figure 21-3). Visual acuity charts with pictures of familiar objects also are available for use with preschool children. Testing with these charts tends to be less accurate than with the Snellen charts. Some children are unable to identify the objects because of lack of recognition, not because of a defect in visual acuity. It is suggested that the Snellen Big E chart be used with preschool children. The acuity of each eye should be measured separately, traditionally beginning with the right eye. Most physicians prefer that the patient wear his or her contact lenses or glasses, except reading glasses, during the test; the medical assistant should record in the patient’s chart that corrective lenses were worn by the patient during the test. An eye occluder should be held over the eye not being tested. The patient’s hand should not be used to cover the eye because this may encourage peeking through the fingers, especially in the case of children. The patient should be instructed to leave open the eye not being tested because closing it causes squinting of the eye that is being tested. The procedure for measuring distance visual acuity is outlined in Procedure 21-1. With minor variations, Procedure 21-1 can be used to test distance visual acuity in preschool children. The Snellen Big E chart is used for this purpose. A child needs a complete and thorough explanation of what is expected of him or her before beginning the test. Tell the child you will be playing a pointing game. Do not force the child to play the game because the results then tend to be inaccurate. Draw the capital letter E on an index card, and teach the child to point in the direction of the open part of the E by turning the card in different directions (up, down, to the right, and to the left). Using such phrases as “fingers” or the “legs of the table” to describe the open part of the E helps the child understand what is expected (Figure 21-4). Allow the child to practice the pointing game with the index card until you are sure this level of skill has been mastered. Be sure to praise the child when the correct response is given. The test is conducted with a card similar to the Snellen eye chart; however, the size of the type ranges from the size of newspaper headlines down to considerably smaller print such as would be found in a telephone directory (Figure 21-5). The test card is available in a variety of forms, such as printed paragraphs, printed words, and pictures. Defects in color vision may be classified as congenital or acquired. Congenital defects are more common and refer to a color vision deficiency that is inherited and is present at birth. Congenital color vision deficiencies most often affect males. Acquired defects refer to a color vision deficiency that is acquired after birth, resulting from such factors as an eye or brain injury, disease, and certain drugs. Color vision tests, such as the Ishihara test (Figure 21-6), detect congenital color vision disturbances and are commonly performed in the medical office. A basic screening for color vision can be performed by asking the patient to identify the red and green lines on the Snellen eye chart. The Ishihara test for color blindness is a convenient and accurate method to detect total congenital color blindness and red-green color blindness by assessing an individual’s ability to perceive primary colors and shades of color. The Ishihara book contains a series of polychromatic plates of primary colored dots arranged to form a numeral against a background of similar dots of contrasting colors (see Figure 21-6). Patients with normal color vision are able to read the appropriate numeral; however, patients with color vision defects read the dots either as not forming a number at all or as forming a number different from the one identified by the individual with normal color vision. The first plate in the Ishihara book is designed to be read correctly by all individuals (with normal vision and exhibiting color vision deficiencies) and should be used to explain the procedure to the patient. If a defect in color vision is detected, the patient is referred for additional assessment of color vision to an ophthalmologist or optometrist, who would use more precise color vision tests. The procedure for assessing color vision using the Ishihara color plates is outlined in Procedure 21-2.

Eye and Ear Assessment and Procedures

Introduction to the Eye

Visual Acuity

Assessment of Distance Visual Acuity (DVA)

Conducting a Snellen Test

Assessing Distance Visual Acuity in Preschool Children

Assessment of Near Visual Acuity (NVA)

Assessment of Color Vision

Ishihara Test

Eye and Ear Assessment and Procedures

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

without correction or

without correction or  with correction. Latin abbreviations are used to record visual acuity. The abbreviation for the right eye is OD (oculus dexter), the abbreviation for the left eye is OS (oculus sinister), and the abbreviation for both eyes is OU (oculus uterque).

with correction. Latin abbreviations are used to record visual acuity. The abbreviation for the right eye is OD (oculus dexter), the abbreviation for the left eye is OS (oculus sinister), and the abbreviation for both eyes is OU (oculus uterque).