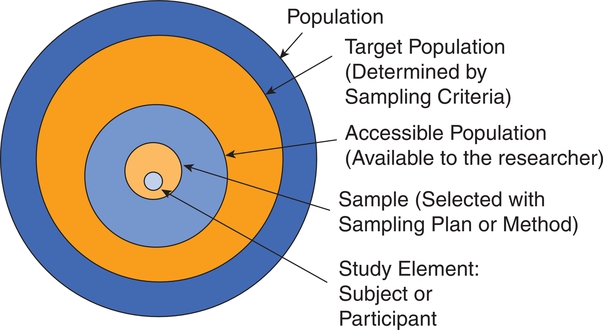

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe sampling theory, including the concepts of population, target population, sampling criteria, sampling frame, subject or participant, sampling plan, sample, representativeness, sampling error, and systematic bias. 2. Critically appraise the sampling criteria (inclusion and exclusion criteria) in published studies. 3. Identify the specific type of probability and nonprobability sampling methods used in published quantitative, qualitative, and outcomes studies. 4. Describe the elements of power analysis used to determine sample size in selected studies. 5. Critically appraise the sample size of quantitative and qualitative studies. 6. Critically appraise the sampling processes used in quantitative, qualitative, and outcomes studies. 7. Critically appraise the settings used in quantitative, qualitative, and outcomes studies. Exclusion sampling criteria, p. 251 Highly controlled setting, p. 278 Inclusion sampling criteria, p. 251 Natural (or field) setting, p. 277 Nonprobability sampling, p. 263 Partially controlled setting, p. 277 Purposeful or purposive sampling, p. 270 Sampling method or plan, p. 255 Sampling or eligibility criteria, p. 251 Simple random sampling, p. 259 Stratified random sampling, p. 260 The population is a particular group of individuals or elements, such as people with type 2 diabetes, who are the focus of the research. The target population is the entire set of individuals or elements who meet the sampling criteria (defined in the next section), such as female, 18 years of age or older, new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes confirmed by the medical record, and not on insulin. Figure 9-1 demonstrates the link of the population, target population, and accessible population in a study. An accessible population is the portion of the target population to which the researcher has reasonable access. The accessible population might include elements within a country, state, city, hospital, nursing unit, or primary care clinic, such as the individuals with diabetes who were provided care in a primary care clinic in Arlington, Texas. Researchers obtain the sample from the accessible population by using a particular sampling method or plan, such as simple random sampling. The individual units of the population and sample are called elements. An element can be a person, event, object, or any other single unit of study. When elements are persons, they are referred to as participants or subjects (see Figure 9-1). Quantitative and outcomes researchers refer to the people they study as subjects or participants. Qualitative researchers refer to the individuals they study as participants. Generalization extends the findings from the sample under study to the larger population. In quantitative and outcomes studies, researchers obtain a sample from the accessible population with the goal of generalizing the findings from the sample to the accessible population and then, more abstractly, to the target population (see Figure 9-1). The quality of the study and consistency of the study’s findings with the findings from previous research in this area influence the extent of the generalization. If a study is of high quality, with findings consistent with previous research, then researchers can be more confident in generalizing their findings to the target population. For example, the findings from the study of female patients with a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in a primary care clinic in Arlington, Texas, may be generalized to the target population of women with type 2 diabetes managed in primary care clinics. With this information, you can decide whether it is appropriate to use this evidence in caring for the same type of patients in your practice, with the goal of moving toward evidence-based practice (EBP; Brown, 2014; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011). When the quantitative or outcomes study is completed, the findings are often generalized from the sample to the target population that meets the sampling criteria (Fawcett & Garity, 2009). Researchers may narrowly define the sampling criteria to make the sample as homogeneous (or similar) as possible to control for extraneous variables. Conversely, the researcher may broadly define the criteria to ensure that the study sample is heterogeneous, with a broad range of values or scores on the variables being studied. If the sampling criteria are too narrow and restrictive, researchers may have difficulty obtaining an adequately sized sample from the accessible population, which can limit the generalization of findings. In discussing the generalization of quantitative study findings in a published research report, investigators sometimes attempt to generalize beyond the sampling criteria. Using the example of the early ambulation preoperative teaching study, the sample may need to be limited to subjects who speak and read English because the preoperative teaching is in English and one of the measurement instruments requires that subjects be able to read English. However, the researchers may believe that the findings can be generalized to non–English-speaking persons. When reading studies, you need to consider carefully the implications of using these findings with a non–English-speaking population. Perhaps non–English-speaking persons, because they come from another culture, do not respond to the teaching in the same way as that observed in the study population. When critically appraising a study, examine the sample inclusion and exclusion criteria, and determine whether the generalization of the study findings is appropriate based on the study sampling criteria. (Chapter 11 provides more detail on generalizing findings from studies.) Representativeness means that the sample, accessible population, and target population are alike in as many ways as possible (see Figure 9-1). In quantitative and outcomes research, you need to evaluate representativeness in terms of the setting, characteristics of the subjects, and distribution of values on variables measured in the study. Persons seeking care in a particular setting may be different from those who seek care for the same problem in other settings or those who choose to use self-care to manage their problems. Studies conducted in private hospitals usually exclude low-income patients. Other settings may exclude older adults or those with less education. People who do not have access to care are usually excluded from studies. Subjects in research centers and the care that they receive are different from patients and the care that they receive in community hospitals, public hospitals, veterans’ hospitals, or rural hospitals. People living in rural settings may respond differently to a health situation from those who live in urban settings. Thus the setting identified in published studies does influence the representativeness of the sample. Researchers who gather data from subjects across a variety of settings have a more representative sample of the target population than those limiting the study to a single setting. A sample must be representative in terms of characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity, income, and education, which often influence study variables. These are examples of demographic or attribute variables that might be selected by researchers for examination in their study. Researchers analyze data collected on the demographic variables to produce the sample characteristics—characteristics used to provide a picture of the sample. These sample characteristics must be reasonably representative of the characteristics of the population. If the study includes groups, the subjects in the groups must have comparable demographic characteristics (see Chapter 5 for more details on demographic variables and sample characteristics). Studies that obtain data from large databases have more representative samples. For example, Monroe, Kenaga, Dietrich, Carter, and Cowan (2013) examined the prevalence of employed nurses enrolled in substance use monitoring programs by examining data from the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) 2010 Survey of Regulatory Boards Disciplinary Actions on Nurses. This NCSBN survey included the United States and its territories and found that 17,085 (0.51%) of the employed nurses were enrolled in substance use monitoring programs. This study examined data from multiple sites (United States and its territories) and included a large national population of nurses (all employed nurses), resulting in a representative sample. The probability of systematic variation increases when the sampling process is not random. Even in a random sample, however, systematic variation can occur when a large number of the potential subjects declines participation. As the number of subjects declining participation increases, the possibility of a systematic bias in the study becomes greater. In published studies, researchers may identify a refusal rate, which is the percentage of subjects who declined to participate in the study, and the subjects’ reasons for not participating (Grove, Burns, & Gray, 2013). The formula for calculating the refusal rate in a study is as follows: You can also calculate the acceptance and refusal rates as follows: Or: In this example, the overall sample attrition rate was considerable (41%), and the rates differed for the two groups to which the subjects were assigned. You can also calculate the attrition rates for the groups. If the two groups were equal at the start of the study and each included 38 subjects, then the attrition rate for the treatment group was (12 ÷ 38) × 100% = 0.316 × 100% = 31.6% = 32%. The attrition for the comparison group was (19 ÷ 38) x 100% = 0.5 × 100% = 50%. Systematic variation is greatest when a large number of subjects withdraw from the study before data collection is completed or when a large number of subjects withdraw from one group but not the other(s) in the study. In studies involving a treatment, subjects in the comparison group who do not receive the treatment may be more likely to withdraw from the study. However, sometimes the attrition is higher for the treatment group if the intervention is complex and/or time-consuming (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). In the early ambulation preoperative teaching example, there is a strong potential for systematic variation because the sample attrition rate was large (41%) and the attrition rate in the comparison group (50%) was larger than the attrition rate in the treatment group (32%). The increased potential for systematic variation results in a sample that is less representative of the target population. Or: Or: From a sampling theory perspective, each person or element in the population should have an opportunity to be selected for the sample. One method of providing this opportunity is referred to as random sampling. For everyone in the accessible population to have an opportunity for selection in the sample, each person in the population must be identified. To accomplish this, the researcher must acquire a list of every member of the population, using the sampling criteria to define eligibility. This list is referred to as the sampling frame. In some studies, the complete sampling frame cannot be identified because it is not possible to list all members of the population. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) has also increased the difficulty in obtaining a complete sampling frame for many studies because of its requirements to protect individuals’ health information (see Chapter 4 for more information on HIPAA). Once a sampling frame is identified, researchers select subjects for their studies using a sampling plan or method. increase representativeness and decrease systematic variation or bias in quantitative and outcomes studies. When critically appraising a study, identify the study sampling plan as probability or nonprobability, and determine the specific method or methods used to select the sample. The different types of probability and nonprobability sampling methods are introduced next. There are four sampling designs that achieve probability sampling included in this text—simple random sampling, stratified random sampling, cluster sampling, and systematic sampling. Table 9-1 identifies the common probability and nonprobability sampling methods used in nursing studies, their applications, and their representativeness for the study. Probability and nonprobability sampling methods are used in quantitative and outcomes studies, and nonprobability sampling methods are used in qualitative studies (Fawcett & Garity, 2009; Munhall, 2012). Table 9-1 Probability and Nonprobability Sampling Methods

Examining Populations and Samples in Research

Understanding Sampling Concepts

Populations and Elements

Sampling or Eligibility Criteria

Representativeness of a Sample in Quantitative and Outcomes Research

Acceptance and Refusal Rates in Studies

Sample Attrition and Retention Rates in Studies

Sampling Frames

Sampling Methods or Plans

Probability Sampling Methods

Sampling Method

Common Application(s)

Representativeness

Probability

Simple random sampling

Quantitative and outcomes research

Strong representativeness of the target population that increases with sample size

Stratified random sampling

Quantitative and outcomes research

Strong representativeness of the target population that increases with control of stratified variable(s)

Cluster sampling

Quantitative and outcomes research

Less representative of the target population than simple random sampling and stratified random sampling

Systematic sampling

Quantitative and outcomes research

Less representative of the target population than simple random sampling and stratified random sampling methods

Nonprobability

Convenience sampling

Quantitative, qualitative, and outcomes research

Questionable representativeness of the target population that improves with increasing sample size; may be representative of the phenomenon, process, or cultural elements in qualitative research

Quota sampling

Quantitative and outcomes research and, rarely, qualitative research

Use of stratification for selected variables in quantitative research makes the sample more representative than convenience sampling.

In qualitative research, stratification might be used to provide greater understanding and increase the representativeness of the phenomenon, processes, or cultural elements.

Purposeful or purposive sampling

Qualitative and sometimes quantitative research

Focus is on insight, description, and understanding of a phenomenon or process with specially selected study participants.

Network or snowball sampling

Qualitative and sometimes quantitative research

Focus is on insight, description, and understanding of a phenomenon or process in a difficult to access population.

Theoretical sampling

Qualitative research

Focus is on developing a theory in a selected area. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Examining Populations and Samples in Research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access