Chapter 7 Evidence-Based Practice in Medical-Surgical Nursing

1. Define evidence-based practice (EBP).

2. Describe the process of how best current evidence is used to make clinical decisions.

3. Explain how to use an EBP approach to identifying a clinical problem, issue, or challenge.

4. Formulate a focused clinical question about clinical practice.

5. List the steps of how to perform a systematic literature review to answer clinical questions.

6. Briefly describe two models of EBP.

7. Explain the steps of the evidence-based practice improvement (EBPI) model.

8. Discuss how the EBPI model can be used to guide a clinical practice improvement project.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Overview

In 2010, the IOM in partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation published The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (Institute of Medicine, 2010). Among the four major recommendations is “Nurses should be full partners, with physicians and other health care professionals, in redesigning health care in the United States” (p. 3). The specifics of this recommendation include the need for nurses to be prepared to be full partners in health care improvement efforts. Aspects of this role include “taking responsibility for identifying problems and areas of system waste, devising and developing improvement plans, [and] tracking improvement over time …” (p. 3).

Definitions of Evidence-Based Practice

According to several nursing experts and the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN), EBP incorporates the best current evidence with the expertise of the clinician and the patient’s values and preferences to make a decision about health care (Levin & Lane, 2006; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011). This definition was based on the work of Sackett et al. (2000), who had proposed three components of EBP—best evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values and preferences—as part of the definition of evidence-based medicine.

Ervin (2002) proposed this definition of EBP for nursing: “Evidence-based nursing practice is practice in which nurses make clinical decisions using the best available research and other evidence that is reflected in approved policies, procedures, and clinical guidelines in a particular healthcare agency” (p. 12). DiCenso et al. (2005) further extended this definition to include information about the patient’s clinical state and the setting or circumstances in which health care is being provided.

The EBP process is collaborative and involves all members of the health care team. This model is shared by many health care professions and is not unique to nursing. Therefore, although other professions might refer to the model as evidence-based medicine (EBM) or evidence-based social work similar to how DiCenso et al. (2005) specified the practice of nursing, the authors of this text refer to the model as EBP.

Steps of the Evidence-Based Practice Process

The process of EBP is systematic and includes several steps as presented by Sackett et al. (2000) in the context of practicing and teaching medicine.

1. Asking “burning” clinical questions

2. Finding the very best evidence to try to answer those questions

3. Critically appraising and synthesizing the relevant evidence

4. Making recommendations for practice improvement

5. Implementing accepted recommendations

Asking “Burning” Clinical Questions

Once you critically think about and pose a question about clinical practice, you will need to find out at what level the question needs to be answered (i.e., at the individual patient level, patient population level, or organizational level). If the latter two levels are where the problem exists, then begin to gather background information from the literature and internal evidence from your organization to describe the problem more fully (Levin et al., 2010).

Qualitative Versus Quantitative Questions

• What is the experience of having cancer like for young adults?

• How do older women respond to a residential move to assisted-living facilities?

• What are the differences in nurses’ work culture between acute care and home care agencies?

• What is the effect of using a new assessment tool to predict the likelihood of falling to frequency and severity of falls in patients undergoing hip replacement?

• What is the effect of hydrocolloid dressings compared with silver-impregnated dressings on the rate of wound healing in patients with postsurgical incision wounds?

PICO(T) Format

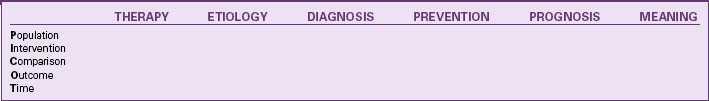

Nursing authors suggest framing clinical questions in a PICO (Cullum et al., 2008; Levin & Lane, 2006) or PICO(T) format. The PICO(T) format is outlined in Table 7-1. The major components of a focused clinical question are the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome, with an added time component when appropriate.

The intervention component pertains to the therapeutic effectiveness of a new treatment and may include (1) exposure to disease or harm, (2) a prognostic factor, or (3) a risk behavior or factor (e.g., the need for toileting to help prevent falls) (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). For example, one might compare a group of smokers to a group of nonsmokers to determine the relationship of smoking to bladder cancer.

Fineout-Overholt and Stillwell (2011) advocated adding a time component or time frame to the focused clinical question. The question may include specifying within what time period one would expect the outcome(s) to occur. An example of a completed PICO(T) question is, What is the effect of adding hourly rounding to the standard falls protocol for the geriatric unit (patients 65 years or older) in hospital Y on the process of care provision (to be more specifically defined) and the outcomes of rate of falls, fall morbidity, and clinician satisfaction within a 3-month period?

Arriving at the focused clinical question is not an easy task, even for seasoned clinicians. Defining the specific question requires these three steps—identifying the problem, clarifying the problem, and focusing the question (Levin & Lane, 2006).

Finding the Best Evidence

• Lack of value for research in practice

• Lack of understanding of organization or structure of electronic databases

• Difficulty accessing research materials

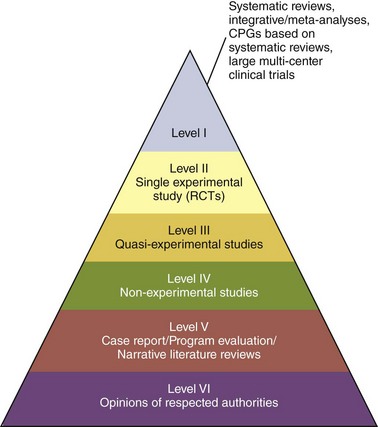

Levels of evidence refers to the status or rank of evidence. Most evidence hierarchies are pyramids with the highest level of evidence at the top (Fig. 7-1). The type of evidence needed depends on the nature of the clinical question—Is the question quantitative or qualitative? For example, if you are asking about the effectiveness of different types of compression bandages on healing of venous leg ulcers, you would want to measure the change in size of the ulcer as one indication of healing (quantitative). On the other hand, you might be interested in what the experience of having a chronic venous ulcer is like for women (qualitative). Each type of question requires different types and sources of evidence to find an answer. Table 7-2 provides an internationally accepted hierarchy for qualitative levels of evidence.

TABLE 7-2 JBI LEVELS OF QUALITATIVE EVIDENCE FOR MEANINGFULNESS*

| LEVEL OF EVIDENCE | MEANINGFULNESS M (1-4) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Meta-synthesis of research with unequivocal synthesized findings |

| 2 | Meta-synthesis of research with credible synthesized findings |

| 3 | a. Meta-synthesis of text/opinion with credible synthesized findings |

| b. One or more single research studies of high quality | |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

* From Joanna Briggs Institute. (2008). Reviewer’s manual. Adelaide, Australia: Author.

A preliminary evidence search entails identifying whether quality clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) exist to answer the clinical question. A clinical practice guideline is an “official recommendation” based on evidence to diagnose and/or manage a health problem (e.g., pain management). If these guidelines are of high quality and they contain the answer to your question, the search may be complete (Levin et al., 2007).

• Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews

• Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) systematic reviews

• Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree