Evidence-Based Practice

Objectives

• Discuss the benefits of evidence-based practice.

• Describe the five steps of evidence-based practice.

• Explain the levels of evidence available in the literature.

• Discuss ways to apply evidence in practice.

• Explain how nursing research improves nursing practice.

• Discuss the steps of the research process.

• Discuss priorities for nursing research.

• Explain the relationship between evidence-based practice and performance improvement.

Key Terms

Bias, p. 57

Clinical guidelines, p. 53

Confidentiality, p. 60

Empirical data, p. 57

Evaluation research, p. 58

Evidence-based practice (EBP), p. 51

Experimental study, p. 57

Generalizable, p. 57

Hypotheses, p. 54

Inductive reasoning, p. 59

Informed consent, p. 60

Nursing research, p. 56

Peer-reviewed, p. 53

Performance improvement (PI), p. 60

PICOT question, p. 52

Qualitative nursing research, p. 59

Quality improvement (QI), p. 60

Quantitative nursing research, p. 57

Reliable, p. 57

Research process, p. 59

Scientific method, p. 57

Valid, p. 57

Variables, p. 54

![]()

Rick has been a registered nurse (RN) on a surgical unit for over 5 years. During that time standard nursing care for patients following abdominal surgery has included getting the patient out of bed, sitting in a chair, and walking within the first postoperative day. Patients are encouraged to walk farther and more frequently each day until they begin to pass gas or have a bowel movement. Rick has noticed lately that several of his patients who have had abdominal surgery have experienced a postoperative ileus. This happens when the patient’s gastrointestinal tract fails to begin moving after surgery (see Chapter 50). When patients have a postoperative ileus, they have increased pain and are in the hospital longer. Rick raises the question with the other RNs in the department, “What if we had our patients sit and rock in a rocking chair instead of sitting in a regular high-back chair after abdominal surgery? Is it possible that rocking after surgery will decrease the incidence of postoperative ileus?”

Most nurses like Rick practice nursing according to what they learn in nursing school, their experiences in practice, and the policies and procedures of their institution. Such an approach to practice does not guarantee that nursing practice is always based on up-to-date scientific information. Sometimes nursing practice is based on tradition and not on current evidence. If Rick went to the scientific literature for articles about how to prevent postoperative ileus, he would find some studies that indicate that simple changes in activity such as encouraging patients to rock in a rocking chair following surgery may help them recover more quickly. The evidence from research and the opinions of nursing experts provide a basis for Rick and his colleagues to make evidence-based changes to their care of patients following abdominal surgery. The use of evidence in practice enables clinicians like Rick to provide the highest quality of care to their patients and families.

A Case for Evidence

Nurses practice in an “age of accountability” in which quality and cost issues drive the direction of health care (Makadon et al., 2010; Moore et al., 2010). The general public is more informed about their own health and the incidence of medical errors within health care institutions across the country. Greater scrutiny is being given as to why certain health care approaches are used, which ones work, and which ones do not. As a result, evidence-based practice (EBP) is a guide to help nurses make effective, timely, and appropriate clinical decisions in response to the broad political, professional, and societal forces that nurses and other health professionals are confronted with daily (Scott and McSherry, 2009).

Nurses face important clinical decisions when caring for patients (e.g., what to assess in a patient and what interventions are best to use). It is important to translate best evidence into best practices at a patient’s bedside. For example, changing how patients are cared for after abdominal surgery is one way that Rick (see previous case study) can use evidence at the bedside. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a problem-solving approach to clinical practice that integrates the conscientious use of best evidence in combination with a clinician’s expertise and patient preferences and values in making decisions about patient care (Fig. 5-1) (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011; Sackett et al., 2000). Today EBP is becoming a goal of all health care institutions and an expectation of professional nurses who are expected to use current evidence when caring for patients (Ingersoll et al., 2010).

Nurses find evidence in different places. A good textbook incorporates evidence into the practice guidelines and procedures it describes. However, a textbook relies on scientific literature, which is sometimes outdated by the time the book is published. Articles from nursing and the health care literature are available on almost any topic involving nursing practice in either journals or on the Internet. Although the scientific basis of nursing practice has grown, some practices are not yet “research based” (Titler et al., 2001). The challenge is to obtain the very best, most current accurate information at the right time, when you need it for patient care.

The best information is the evidence that comes from well-designed, systematically conducted research studies, mostly found in scientific journals. Unfortunately much of that evidence never reaches the bedside. Nurses in practice settings, unlike in educational settings, do not always have easy access to databases for scientific literature. Instead, they often care for patients on the basis of tradition or convenience. Another source of information comes from nonresearch evidence, including quality improvement and risk management data; international, national, and local standards; infection control data; benchmarking, retrospective, or concurrent chart reviews; and clinicians’ expertise. It is important to rely more on research evidence rather than solely on nonresearch evidence. When you face a clinical problem, always ask yourself where you can find the best evidence to help you find the best solution in caring for patients.

Even when you use the best evidence available, application and outcomes will differ based on your patient’s values, preferences, concerns, and/or expectations (Oncology Nursing Society [ONS], n.d.). As a nurse, you develop critical thinking skills to determine whether evidence is relevant and appropriate to your patients and to a clinical situation. For example, a single research article suggests that the use of therapeutic touch is effective in reducing abdominal incision pain. However, if your patient’s cultural beliefs prevent the use of touch, you will likely need to search for a better evidence-based therapy that patients will accept. Using your clinical expertise and considering patient values and preferences ensures that you apply the evidence available in practice both safely and appropriately.

Steps of Evidence-Based Practice

EBP is a systematic approach to rational decision making that facilitates achievement of best practices. A step-by-step approach ensures that you obtain the strongest available evidence to apply in patient care (Oh et al., 2010). There are six steps of EBP (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011):

2. Collect the most relevant and best evidence.

3. Critically appraise the evidence you gather.

5. Evaluate the practice decision or change.

Ask a Clinical Question.

Always think about your practice when caring for patients. Question what does not make sense to you and what needs to be clarified. Think about a problem or area of interest that is time consuming, costly, or not logical (Stilwell et al., 2010). Use problem- and knowledge-focused triggers to think critically about clinical and operational nursing unit issues (Titler et al., 2001). A problem-focused trigger is one you face while caring for a patient or a trend you see on a nursing unit. For example, while Rick is caring for patients following abdominal surgery, he wonders, “If we changed our patients’ activity levels after surgery, would they experience fewer episodes of postoperative ileus?” Other examples of problem-focused trends include the increasing number of patient falls or incidence of urinary tract infections on a nursing unit. Such trends lead you to ask, “How can I reduce falls on my unit?” or “What is the best way to prevent urinary tract infections in postoperative patients?”

A knowledge-focused trigger is a question regarding new information available on a topic. For example, “What is the current evidence to improve pain management in patients with migraine headaches?” Important sources of this type of information are standards and practice guidelines available from national agencies such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the American Pain Society (APS), or the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN). Other sources of knowledge-focused triggers include recent research publications and nurse experts within an organization.

Sometimes you use data gathered from a health care setting to examine clinical trends to develop clinical questions. For example, most hospitals keep monthly records on key quality of care or performance indicators such as medication errors or infection rates. All magnet-designated hospitals maintain the National Database of Nursing Quality Improvement (NDNQI) (see Chapter 2). The database includes information on falls, pressure ulcer incidence, and nurse satisfaction. Typically quality and risk management data do not give you evidence in finding a solution to a problem, but the data inform you about the nature or severity of problems that then allow you to form practice questions.

The questions you ask eventually lead you to the evidence for an answer. When you ask a question and then go to the scientific literature, you do not want to read 100 articles to find the handful that are most helpful. You want to be able to read the best four-to-six articles that specifically address your practice question. Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2011) suggest using a PICOT format to state your question. The five elements of a PICOT question are summarized in Box 5-1. The more focused a question you ask, the easier it becomes to search for evidence in the scientific literature. For example, Rick develops the following PICOT question: Do patients who have had abdominal surgery (P) and who rock in a rocking chair (I) have a reduced incidence of postoperative ileus (O) during hospitalization (T) when compared with patients who receive standard nursing care following surgery (C)? Another example is: Is an adult patient’s (P) blood pressure more accurate (O) when measuring with the patient’s legs crossed (I) versus the patient’s feet flat on the floor (C)?

Proper question formatting allows you to identify key words to use when conducting your literature search. Note that a well-designed PICOT question does not have to follow the sequence of P, I, C, O, and T. In addition, intervention (I), comparison (C), and time (T) are not appropriate to be used in every question. The aim is to ask a question that contains as many of the PICOT elements as possible. For example, here is a meaningful question that contains only a P and O: How do patients with cystic fibrosis (P) rate their quality of life (O)?

Inappropriately formed questions (e.g., What is the best way to reduce wandering? What is the best way to improve family’s satisfaction with patient care?) are background questions that will likely lead to many irrelevant sources of information, making it difficult to find the best evidence. Sometimes a background question is needed to identify a more specific PICOT question. The PICOT format allows you to ask questions that are intervention focused. For questions that are not intervention focused, the meaning of the letter I can be an area of interest (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). For example, What is the difference in retention (O) of new nursing graduates (P) who have previous experience as nurse assistants (I) versus those who do not (C)?

The questions you ask using a PICOT format help to identify knowledge gaps within a clinical situation. When you raise well–

thought-out questions, you should understand the evidence that is missing to guide clinical practice. Remember: do not be satisfied with clinical routines. Always question and use critical thinking to consider better ways to provide patient care.

Collect the Best Evidence.

Once you have a clear and concise PICOT question, you are ready to search for evidence. You can find the evidence you need in a variety of sources: agency policy and procedure manuals, quality improvement data, existing clinical practice guidelines, or computerized bibliographical databases. Do not hesitate to ask for help to find appropriate evidence. Your faculty is always a key resource. When you are assigned to a health care setting, use agency experts such as advanced practice nurses, staff educators, risk managers, and infection control nurses.

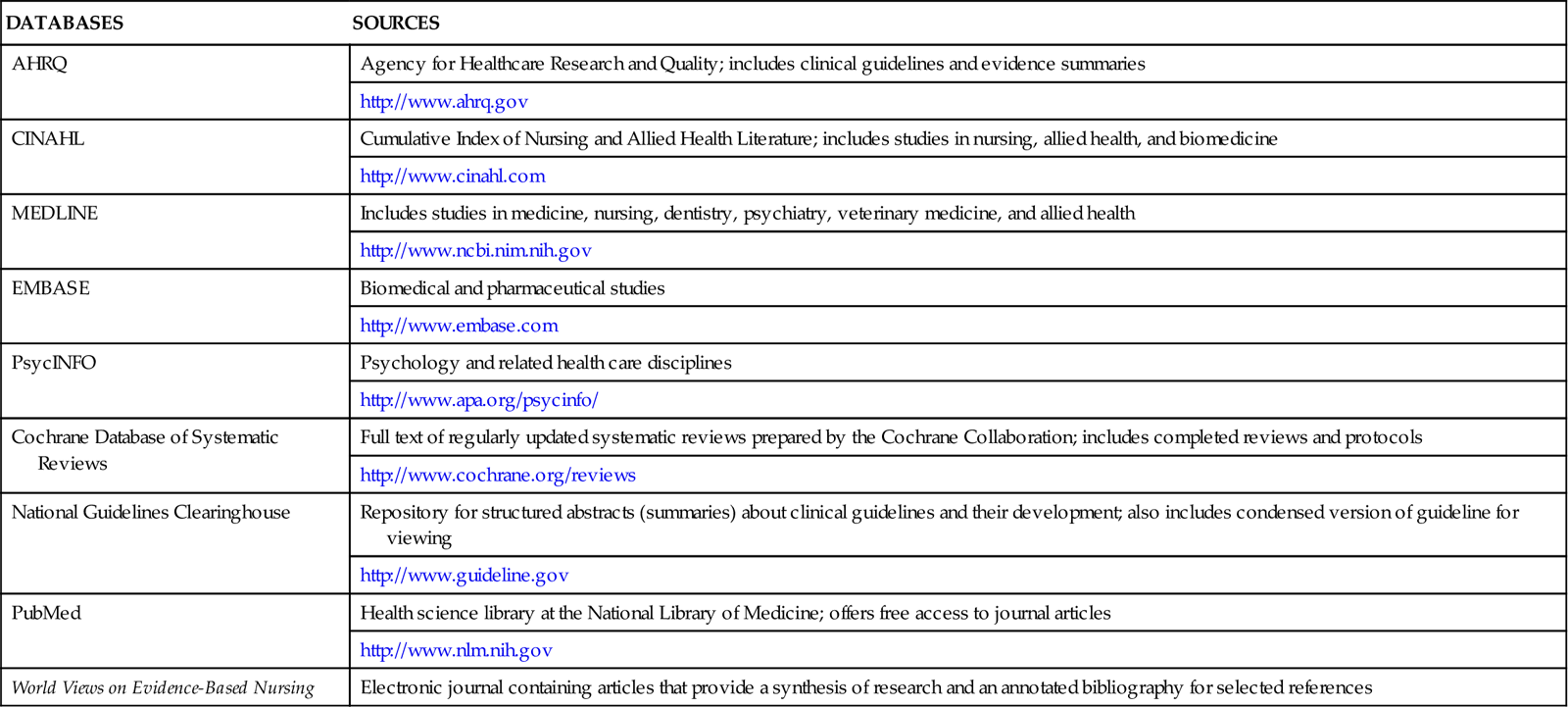

When using the scientific literature for evidence, seek the assistance of a medical librarian. He or she knows the various databases that are available to you (Table 5-1). The databases contain large collections of published scientific studies, including peer-reviewed research. A peer-reviewed article is one reviewed by a panel of experts familiar with the topic or subject matter of the article before it was published. The librarian is available to help translate your PICOT question into the language or key words that will yield the best evidence search. When conducting a search, it is necessary to enter and manipulate different key words until you get the combination that gives you the key articles that you want to read about your question. When you enter a word to search into a database, be prepared for some confusion with the evidence you obtain. The vocabulary within published articles is often vague. The word you select sometimes has one meaning to one author and a very different meaning to another.

TABLE 5-1

Searchable Scientific Literature Databases and Sources

| DATABASES | SOURCES |

| AHRQ | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; includes clinical guidelines and evidence summaries |

| http://www.ahrq.gov | |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature; includes studies in nursing, allied health, and biomedicine |

| http://www.cinahl.com | |

| MEDLINE | Includes studies in medicine, nursing, dentistry, psychiatry, veterinary medicine, and allied health |

| http://www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov | |

| EMBASE | Biomedical and pharmaceutical studies |

| http://www.embase.com | |

| PsycINFO | Psychology and related health care disciplines |

| http://www.apa.org/psycinfo/ | |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | Full text of regularly updated systematic reviews prepared by the Cochrane Collaboration; includes completed reviews and protocols |

| http://www.cochrane.org/reviews | |

| National Guidelines Clearinghouse | Repository for structured abstracts (summaries) about clinical guidelines and their development; also includes condensed version of guideline for viewing |

| http://www.guideline.gov | |

| PubMed | Health science library at the National Library of Medicine; offers free access to journal articles |

| http://www.nlm.nih.gov | |

| World Views on Evidence-Based Nursing | Electronic journal containing articles that provide a synthesis of research and an annotated bibliography for selected references |

When Rick searches for evidence to answer his PICOT question, he asks for help from a medical librarian. The medical librarian helps him learn how to choose alternative words or terms that identify his PICOT question. During their search Rick identifies three research articles published since 1990 that address the effects of rocking in a rocking chair on return of bowel function following abdominal surgery (Massey, 2010; Moore et al., 1995; Thomas et al., 1990).

MEDLINE and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) are among the best-known comprehensive databases to search for scientific knowledge in health care (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Among the many databases, some are available through vendors at a cost, some are free of charge, and some offer both options. As a student you have access to an institutional subscription through a vendor purchased by your school. One of the more common vendors is OVID, which offers several different databases. Databases are also available free on the Internet. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews is a valuable source of high-quality evidence. It includes the full text of regularly updated systematic reviews and protocols for reviews currently under way. Collaborative review groups prepare and maintain the reviews. The protocols provide the background, objectives, and methods for reviews in progress (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). The National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC) is a database supported by the AHRQ. It contains clinical guidelines, systematically developed statements about a plan of care for a specific set of clinical circumstances involving a specific patient population. Examples of clinical guidelines on NCG include care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and practice guidelines for the treatment of adults with low back pain. The NGC is invaluable when developing a plan of care for a patient (see Chapter 18).

Fig. 5-2 represents the hierarchy of available evidence. The level of rigor or amount of confidence you can have in a study’s findings decreases as you move down the pyramid. At this point in your nursing career, you cannot be an expert on all aspects of the types of studies conducted. But you can learn enough about the types of studies to help you know which ones have the best scientific evidence. At the top of the pyramid are systematic reviews or meta-analyses, which are state-of-the-art summaries from an individual researcher or panel of experts. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews are the perfect answers to PICOT questions because they rigorously summarize current evidence.

During either a meta-analysis or a systematic review, a researcher asks a PICOT question, reviews the highest level of evidence available (e.g., randomized controlled trials [RCTs]), summarizes what is currently known about the topic, and reports if current evidence supports a change in practice or if further study is needed. The main difference is that in a meta-analysis the researcher uses statistics to show the effect of an intervention on an outcome, whereas in a systematic review no statistics are used to draw conclusions about the evidence. In the Cochrane Library all entries include information on meta-analyses and systematic reviews. If you use MEDLINE or CINAHL, enter a textword such as “meta-analysis” or “systematic review” or the MeSH heading of evidence-based medicine to obtain scientific reviews on your PICOT question.

The RCT is the most precise form of experimental study and therefore is the gold standard for research. A single RCT is not as conclusive as a review of several RCTs on the same question. However, a single RCT that tests the intervention included in your question yields very useful evidence. If RCTs are not available, you can use results from other research studies such as descriptive or qualitative studies to help answer your PICOT question. The use of clinical experts may be at the bottom of the evidence pyramid, but do not consider clinical experts to be a poor source of evidence. Expert clinicians use evidence frequently as they build their own practice, and they are rich sources of information for clinical problems.

Critically Appraise the Evidence.

Perhaps the most difficult step in the EBP process is critiquing or analyzing the available evidence. Critiquing evidence involves evaluating it, which includes determining the value, feasibility, and usefulness of evidence for making a practice change (ONS, n.d.). When critiquing evidence, first evaluate the scientific merit and clinical applicability of the findings of each study. Then with a group of studies and expert opinion determine what findings have a strong enough basis for use in practice. After critiquing the evidence you will be able to answer the following questions. Do the articles together offer evidence to explain or answer my PICOT question? Do the articles show support for the reliability and validity of the evidence? Can I use the evidence in practice?

As a student new to nursing, it takes time to acquire the skills to critique evidence like an expert. When you read an article, do not put it down and walk away because of the statistics and technical language. Know the elements of an article and use a careful approach when reviewing each one. Evidence-based articles include the following elements:

• Manuscript narrative. The “middle section” or narrative of an article differs according to the type of evidence-based article it is (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). A clinical article describes a clinical topic, which often includes a description of a patient population, the nature of a certain disease or health alteration, how patients are affected, and the appropriate nursing therapies. An author sometimes writes a clinical article to explain how to use a therapy or new technology. A research article contains several subsections within the narrative, including the following:

After Rick critiques each article for his PICOT question, he combines the findings from the three articles he found about the use of rocking chairs to determine the state of the evidence. He uses critical thinking to consider the scientific rigor of the evidence and how well it answers his PICOT question. He also considers the evidence in light of his patients’ concerns and preferences. As a clinician Rick judges whether to use the evidence for the group of patients for whom he normally cares on the surgical unit. Patients frequently have complex medical histories and patterns of responses (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Ethically it is important for Rick to consider evidence that will benefit patients and do no harm. He needs to decide if the evidence is relevant, is easily applicable in his setting of practice, and has the potential for improving patient outcomes.

Integrate the Evidence.

Once you decide that the evidence is strong and applicable to your patients and clinical situation, incorporate it into practice. Your first step is simply to apply the research in your plan of care for a patient (see Chapter 18). Use the evidence you find as a rationale for an intervention you plan to try. For instance, you learned about an approach to bathe older adults who are confused and decide to use the technique during your next clinical assignment. You use the bathing technique with your own assigned patients, or you work with a group of other students or nurses to revise a policy and procedure or develop a new clinical protocol.

The literature Rick found reveals that rocking in a rocking chair after bowel surgery usually results in a quicker return of bowel function following surgery when compared with standard nursing care (Massey, 2010; Moore et al., 1995; Thomas et al., 1990). Rick then meets with his colleagues on the unit practice committee to recommend a protocol for patients who have abdominal surgery. The protocol outlines guidelines to have patients routinely sit in rocking chairs when they get out of bed after surgery.

Evidence is integrated in a variety of ways through teaching tools, clinical practice guidelines, policies and procedures, and new assessment or documentation tools. Depending on the amount of change needed to apply evidence in practice, it becomes necessary to involve a number of staff from a given nursing unit. It is important to consider the setting where you want to apply the evidence. Is there support from all staff? Does the practice change fit with the scope of practice in the clinical setting? Are resources (time, secretarial support, and staff) available to make a change? When evidence is not strong enough to apply in practice, your next option is to conduct a pilot study to investigate your PICOT question. A pilot study is a small-scale research study or one that includes a quality or performance improvement project.

Evaluate the Practice Decision or Change.

After applying evidence in your practice, your next step is to evaluate the outcome. How does the intervention work? How effective was the clinical decision for your patient or practice setting? Sometimes your evaluation is as simple as determining if the expected outcomes you set for an intervention are met (see Chapters 18 and 20). For example, after the use of a transparent intravenous (IV) dressing, does the IV dislodge, or does the patient develop the complication of phlebitis? When using a new approach to preoperative teaching, does the patient learn what to expect after surgery?

When an EBP change occurs on a larger scale, an evaluation is more formal. For example, evidence showing factors that contribute to pressure ulcers might lead a nursing unit to adopt a new skin care protocol. To evaluate the protocol, nurses track the incidence of pressure ulcers over a course of time (e.g., 6 months to a year). In addition, they collect data to describe both patients who develop ulcers and those who do not. This comparative information is valuable in determining the effects of the protocol and whether modifications are necessary.

When evaluating an EBP change, determine if the change was effective, if modifications in the change are needed, or if the change needs to be discontinued. Events or results that you do not expect may occur. For example, a hospital that implements a new method of cleaning IV line puncture sites discovers an increased rate of IV line infections and reevaluates the new cleaning method to determine why infections have increased. If the hospital does not evaluate this change in practice, more patients will develop IV site infections. Never implement a practice change without evaluating its effect.

In Rick’s case the unit practice committee collects evaluation data after 3 months of implementing the rocking chair protocol to determine if patients experienced a lower incidence of postoperative ileus following abdominal surgery. After completing chart reviews, the committee discovers that patients who used the rocking chairs following abdominal surgery experienced fewer incidences of postoperative ileus compared with patients who did not use rockers before the protocol was implemented. The protocol patients went home 1 to 2 days sooner than the patients who did not use the rocking chairs. Patient interviews revealed that the patients were satisfied with the rocking movement and that, not only did the rocking chairs help them pass gas faster, but the patients also felt less anxious because of the rocking motion. After talking with the committee, Rick discovered that not all patients were able to use rocking chairs during this time because the unit did not have enough rocking chairs. He presented these data to his manager who approved the purchase of more rocking chairs.

Share the Outcomes with Others.

After implementing an EBP change, it is important to communicate the results. If you implement an evidence-based intervention with one patient, you and the patient determine the effectiveness of that intervention. When a practice change occurs on a nursing unit level, the first group to discuss the outcomes of the change is often the clinical staff on that unit. To enhance professional development and promote positive patient outcomes beyond the unit level, share the results with various groups of nurses or other care providers such as the nursing practice council or the research council. Clinicians enjoy and appreciate seeing the results of a practice change. In addition, the practice change will more likely be sustainable and remain in place when staff are able to see the benefits of an EBP change.

As a professional nurse it is critical to contribute to the growing knowledge of nursing practice, especially if he or she is involved in an EBP change. Nurses often communicate the outcomes of EBP changes at professional conferences and meetings. Being involved in professional organizations allows them to present EBP changes in scientific abstracts, poster presentations, or even podium presentations.

After evaluating the results of the EBP change, Rick decides to present the outcomes to the nursing research committee at his hospital. The chief nursing officer hears Rick’s presentation and encourages him to submit an abstract about his EBP change to a national professional nursing conference. Rick submits his abstract for consideration as a poster presentation at the annual Midwest Nursing Research Society conference, and it is accepted. During the conference Rick tells other nurses about his EBP change and is contacted by several nurses after the conference who are thinking about implementing the use of rocking chairs on their patient care units.

Nursing Research

After completing a thorough review and critique of the scientific literature, you might not have enough strong evidence to make a practice change. Instead you may find a gap in knowledge that makes your PICOT question go unanswered. When this happens, the best way to answer your PICOT question is to conduct a research study. At this time in your career you will not be conducting research. However, it is important for you to understand the process of nursing research and how it generates new knowledge.

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2007) supports the need for nursing research as a means for improving the health and welfare of people. Nursing research is a way to identify new knowledge, improve professional education and practice, and use resources effectively. Research means to search again or to examine carefully. It is a systematic process that asks and answers questions to generate knowledge. The knowledge provides a scientific basis for nursing practice and validates the effectiveness of nursing interventions. Nursing research improves professional education and practice and helps nurses use resources effectively. The scientific knowledge base of nursing continues to grow today, thus furnishing evidence nurses can use to provide safe and effective patient care. Many professional and specialty nursing organizations support the conduct of research for advancing nursing science.

An example of how research can expand our practice can be seen in the work of Dr. Norma Metheny who has spent many years asking questions about how to prevent the aspiration of tube feeding in patients who receive feeding through nasogastric tubes (Metheny et al., 1988, 1989, 1990, 1994, 2000). Through her research she identified factors that increase the risk for aspiration and approaches to use in determining tube feeding placement. Dr. Metheny’s findings are incorporated into this textbook and have changed the way nurses administer tube feedings to patients. Through research Dr. Metheny has contributed to the scientific body of knowledge that has saved patients’ lives and helped to prevent the serious complication of aspiration.

Outcomes Management Research

The management of care delivery outcomes is a growing concern for nurse clinicians and researchers (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Outcomes research assesses and documents the effectiveness of health care services and interventions. It responds to the increased demands from policy makers, insurers, and the public to justify care practices and systems in terms of improved patient outcomes and costs (Polit and Beck, 2007). For example, studying the effects of an outpatient education program on the ability of older adult patients to follow a nutrition and exercise program is an outcome study.

Care delivery outcomes are the observable or measurable effects of some intervention or action (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). As is the case with the expected outcomes you develop in a plan of care (see Chapter 18), a care delivery outcome focuses on the recipient of service (e.g., patient, family, or community) and not the provider (e.g., nurse or physician). For example, an outcome of a diabetes education program is that patients are able to self-administer insulin, not the nurses’ success in instructing all patients newly diagnosed with diabetes.

A problem in outcomes research is the clear definition or selection of measurable outcomes. Components of an outcome include the outcome itself, how it is observed (the indicator), its critical characteristics (how it is measured), and its range of parameters (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). For example, health care settings commonly measure the outcome of patient satisfaction when they introduce new services (e.g., new care delivery model or outpatient clinic). The outcome is patient satisfaction, observed through patients’ responses to a patient satisfaction instrument, including characteristics such as nursing care, physician care, support services, and the environment. Patients complete the instrument, responding to a scale (parameter) designed to measure their degree of satisfaction (e.g., scale of 1 to 5). The combined score on the instrument yields a measure of patient satisfaction, an outcome that the facility can track over time.

Although the nursing literature now addresses the identification of “nursing-sensitive outcomes” (Box 5-2), or outcomes that are sensitive to nursing practice (Ingersoll et al., 2010; Montalvo, 2007), researchers frequently choose outcomes that do not measure a true impact of care delivery, particularly nursing care delivery. For example, common outcome measures include morbidity, mortality, readmission rate, or length of stay. Although important outcomes to understand, they do not always measure the true effect of a specific nursing intervention on care delivery. For example, if a nurse researcher intends to measure the success of a nurse-initiated protocol to manage blood glucose levels in critically ill patients, the researcher will not likely measure mortality because it is too broad and susceptible to many factors (e.g., the selection of medical therapies, the patients’ acuity of illness) other than the nurse-initiated protocol. Instead, he or she will have a better idea of the effects of the protocol by measuring the outcome of patients’ blood glucose ranges. The nurse researcher obtains the blood glucose level of patients placed on the protocol and compares them to a desired range that represents good blood glucose control.