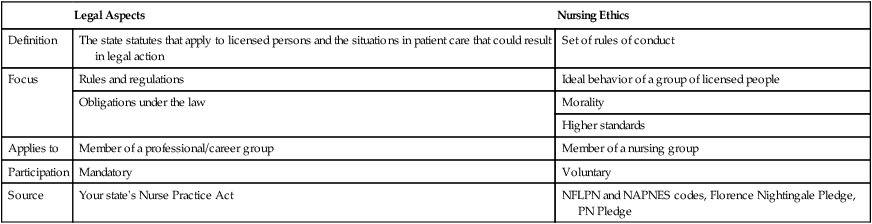

On completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. List four current ethical issues of concern in twenty-first-century health care. 2. Explain the differences among ethics, morals, and values. 3. Differentiate between personal and professional ethics. 4. Identify ethical elements in your state’s Nurse Practice Act. 5. Describe how the role of nursing has changed since the introduction of the nursing process and critical thinking into nursing curricula. 6. Discuss how nonmaleficence is more complex than the definition of “do no harm.” 7. Differentiate between beneficence and paternal beneficence. 8. Explain the steps for an autonomous decision. 9. Describe how fidelity affects nursing care. 10. Discuss how a nurse applies the principle of justice to nursing. 11. Discuss the role of beneficent paternalism. 12. Differentiate between ethical and legal responsibility in nursing. • What actions are right or wrong • If one ought to do something • If one has the right to do something Law is thought of as a minimum ethic that is written and enforced. As a licensed practical/vocational nurse (LPN/LVN), the Nurse Practice Act in your state is your final authority on what you are legally obligated to do as a nurse regardless of where you are employed (see Chapter 12 for more about nursing and the law). Have a thorough knowledge of the Nurse Practice Act in the state in which you are employed. Nursing ethics are similar to, but also different from, the legal aspects that regulate your nursing practice. Table 11-1 presents a comparison of legal aspects and nursing ethics. Table 11-1 Comparison of Legal Aspects and Nursing Ethics Health agencies such as hospitals have a medical ethics committee. This multidisciplinary team assists with difficult ethical decisions. Usually the discussions relate to new or unusual ethical questions. However, if you think the ethics committee makes all the medical ethical decisions, you are only partially right. Patients arrive with their culture- and/or religion-based ethics, which were often established long before they were born. What the person can and cannot do in regard to health care has already been established by the culture of which they are a part. See Chapter 17 for a discussion of spiritual needs, spiritual caring, and religious differences. 1. Individual autonomy means “self-rule.” Individuals have the capacity to think and, based on these thoughts, to make the decision freely whether or not to seek health care (the freedom to choose). 2. Individual rights mean the ability to assert one’s rights. The extent to which a patient can exert his or her rights is restricted (i.e., their rights cannot restrict the rights of others). For example, the patient’s right to refuse treatment can be at odds with the health professional’s perceived duty to act always in a way that will benefit the patient (do good and prevent harm). The individual’s right has become a central theme of health care.

Ethics Applied to Nursing

Personal Versus Professional Ethics

Description and scope of ethics

Morals and values

Comparison of legal aspects of nursing and ethics

Legal Aspects

Nursing Ethics

Definition

The state statutes that apply to licensed persons and the situations in patient care that could result in legal action

Set of rules of conduct

Focus

Rules and regulations

Ideal behavior of a group of licensed people

Obligations under the law

Morality

Higher standards

Applies to

Member of a professional/career group

Member of a nursing group

Participation

Mandatory

Voluntary

Source

Your state’s Nurse Practice Act

NFLPN and NAPNES codes, Florence Nightingale Pledge, PN Pledge

Ethical decisions in health care

Ethics committees

Western secular belief system

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethics Applied to Nursing: Personal Versus Professional Ethics

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access