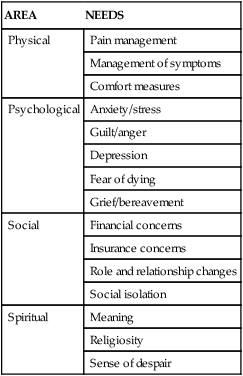

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Discuss legal and ethical issues related to death 3. Discuss measures the nurse can take regarding palliative care 4. Discuss the child’s reaction to death 5. Describe the impact death has on the different age groups 6. Discuss fears of the child related to dying 7. Discuss pain management for the dying child 8. Describe how a terminal illness affects the child and family 9. Describe cultural issues related to death 10. Discuss the benefits of hospice 11. Discuss management of symptoms the dying child may have 12. Discuss the nurse’s role during the end-of-life care of a child One of the most important, if not the most important, preparations for dealing with the dying child is self-exploration. Attitudes about life and death affect our nursing practice. Those attitudes and emotions can form barriers to effective communication unless they are recognized and released. How nurses have or have not dealt with their own losses affects their ability to relate to patients. Nurses must recognize that coping is an active and ongoing process. Constructive outlets such as exercise are critical for the nurse who cares for dying children. An active support system consisting of nonjudgmental people (professional or personal) who are not threatened by natural expressions of emotions is crucial. Taking time off periodically may be necessary. Even attending the child’s funeral may help the nurse in coping and does not detract from professionalism (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). Proper channeling of these feelings can be a valuable part of the nurse’s empathetic response to others. Legal issues related to death revolve around what is made a law by a legally sanctioned group. Legal issues include informed consent, role of a legal guardian, a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order, organ donation, and so on. In addition, each state’s Nurse Practice Act regulates the practice of nursing. An ethical issue relates to what is good or moral. Ethical principles include respect for autonomy, benevolence, nonmaleficence, veracity, confidentiality, fidelity, and justice (Table 22-1). For example, life-sustaining medical treatment (such as a ventilator) may have positive and/or negative implications; ethical principles may be used to evaluate the situation. Use of these principles aids the health care team and the family to provide the dying child with a peaceful and dignified death. Through the use of ethical principles, the unique needs of the child and family can be kept in perspective, as can assisting in resolving dilemmas that can arise during these challenging times. Table 22-1 Ethical Principles and Definitions Palliative care is the care and comfort given to a dying person. Palliative treatment focuses on the “relief of symptoms (e.g., pain, dyspnea) and conditions (e.g., loneliness) that cause distress and detract from the child’s enjoyment of life” (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007). Nurses provide palliative care so that the individual and the family experience a comfortable, supported, and dignified end of life. Palliative care aids the child who is experiencing death and the family to feel cared for and supported and to have this care performed in the most dignified way. The goal of palliative care is to “add life to the child’s years, not simply years to the child’s life” (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007). The American Nurses Association Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001) does not support euthanasia or “mercy killing” by nurses. However, the role of the nurse is to relieve symptoms in the dying patient even if those interventions involve the risk of hastening death (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). When end-of-life care is needed for a child, it brings with it a great deal of emotional feelings. As parents and primary caregivers to a child, parents expect their children to outlive them. In the world of pediatric nursing, nurses assume that their time will be spent on curing and healing in the pediatric population. Nurses, however, must also recognize the value of caring for the child who is dying. The pediatric nurse has much to gain from working with the dying child and assisting the family in confronting issues they must face. In looking back, parents—and indeed, often the child—will look back and recall a time when living with the disease changed to preparing for death. Health care providers who work with children recognize that open and honest communication is the best approach. Broaching this subject with a child is difficult for all concerned. It is an issue that requires communication skills, empathy, and many discussions. The parent and pediatrician may consider the child’s understanding of and prior experience with death, the family’s religious or cultural beliefs, the developmental level of the child, how the child copes with sadness and pain, the disease experience, and the circumstances expected (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007). Box 22-1 discusses some additional issues to consider before the discussion of death with a child. For the child and family to be supported, a multidisciplinary approach is needed. A team approach is most beneficial, particularly one that allows the individual and the family to have input into the decisions that are made. At a minimum, the team includes a physician, nurse, social worker, spiritual advisor, and child life specialist. Needs that should be considered center around physical, psychological, social, and spiritual areas. Table 22-2 lists factors for each of these. Table 22-2 Physical, Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Needs Each child, like each adult, approaches death in an individual way, drawing on limited experience (Table 22-3). Nurses must become well-acquainted with children and view them within the context of their families and social culture. Children’s anxiety about death often centers on symptoms. They fear that the treatments necessary to alleviate their problem may be painful, as indeed some of them are. Their sense of trust is precarious. It is important that nurses be honest and inform children of what is about to be done and why it is necessary. Information should be shared in terms that children can understand. Encourage expression of feelings, such as by saying “You seem angry.” Allow sufficient time for a response. It is important that children be allowed to have as much control over what happens to them as possible. This is fostered by including them in decisions that concern their welfare. Do not, however, offer a choice when there is none. Children often communicate symbolically. Listen to what they are saying to you, to their toys, and to other children. Provide crayons and paper. Drawing feelings is often therapeutic. Table 22-3

End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families

Self-Exploration

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Legal and Ethical Issues Related to Death

PRINCIPLE

DEFINITION

Respect for autonomy

The patient’s right to self-determination and decision making

Benevolence

Doing what is good, meeting needs, balancing benefits with risk and harm, providing relief of pain and suffering

Nonmaleficence

Doing no harm

Veracity

Being honest, telling the truth

Confidentiality

Respecting privileged information; preserving rights, privacy, and dignity

Fidelity

Keeping promises

Justice

Treating fairly, ensuring distribution of resources

Palliative Care

AREA

NEEDS

Physical

Pain management

Management of symptoms

Comfort measures

Psychological

Anxiety/stress

Guilt/anger

Depression

Fear of dying

Grief/bereavement

Social

Financial concerns

Insurance concerns

Role and relationship changes

Social isolation

Spiritual

Meaning

Religiosity

Sense of despair

Child’s Reaction to Death

AGE

CONCEPT

Infant-toddler

Little understanding of death

Fear and anxiety over separation

Preschooler

Something that happens to others

Not permanent

Curious about dead flowers and animals

Magical thinking

Believe that “bad thoughts” may come true, harbor guilt

Believe their thoughts can cause death

Death is reversible

Will not happen to them

Early school years

Death is final

Think they might die, but only in the distant future

May understand death as a “person”

Death is universal

Suspect parents will die “someday”

Fear of mutilation

Preadolescent-adolescent

Able to understand death in a logical manner

Understand death is universal

Understand death is permanent

Fear of disfigurement and isolation from peers ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access