Chapter 9 End-of-Life Care

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Explain the purpose and procedure for advance directives to patients and their families.

2. Describe the importance of collaborating with members of the interdisciplinary team when caring for the dying patient and family or other caregivers.

3. Discuss the ethical and legal obligations of the nurse with regard to end-of-life care.

4. Assess the patient’s and family’s ability to cope with the dying process.

5. Assess and plan interventions to meet the dying patient’s spiritual needs.

6. Incorporate the patient’s cultural practices and beliefs when providing care during the dying process and death.

7. Identify the need for providing psychosocial support to the family or other caregivers during the patient’s dying process.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Overview of Death and Dying

Pathophysiology of Dying

• Heart failure secondary to cardiac dysrhythmias, myocardial infarction, or cardiogenic shock

• Respiratory failure secondary to pulmonary embolism, heart failure, pneumonia, lung disease, or respiratory arrest caused by increased intracranial pressure

• Shock secondary to infection, blood loss, or organ dysfunction, which leads to lack of blood flow (i.e., perfusion) to vital organs

Incidence of Death

Over 2 million deaths occur every year in the United States. The most common causes of death in the United States are diseases of the heart, followed by cancer (Table 9-1).

TABLE 9-1 LEADING CAUSES OF DEATH IN UNITED STATES

Planning for End-of-Life and Advance Directives

Most Americans do not have advance directives, and many health care providers do not talk with patients about their wishes for end-of-life (EOL) care until the patients are unable to make their own decisions. Recent data suggest that older adults want early discussions with their health care provider in preparation for death (Gillick, 2010).

1. Receive information (but not necessarily oriented ×4)

2. Evaluate, deliberate, and mentally manipulate information

By definition, the comatose patient does not have decisional ability. In this case, it becomes unclear as to how health care decisions will be made, who has the authority to make them, and what the treatment should be (Perrin, 2010a).

There are two general types of advance directives. The first is an instructional directive, which states the type and amount of care a person would want if he or she were to become incapacitated. Living wills and medical directives, such as do not resuscitate (DNR) orders, are examples of instructional directives (Perrin, 2010a).

Ethics and DNR Orders

Unfortunately, most patients do not obtain a portable DNR. In this case, DNR orders are usually written only a day or two before the patient’s death. In general, physicians do not want to have emotional and time-consuming EOL conversations in advance. However, nurses are willing to discuss DNR options with patients and their families so that they can be involved in their own EOL decisions (Morrell et al., 2008). According to the American Nurses Association Code of Ethics, nurses have an ethical obligation to ensure that the patient, health care proxy, or surrogate has timely information about expected care outcomes to help them make the best possible decisions (Lachman, 2010).

A major problem with DNR orders is their unclear variations, including partial DNR (e.g., cardiac DNR or Do Not Intubate) or “slow code” orders. Several authors have suggested that these orders are medically and ethically inappropriate (Venneman et al., 2008). Instead, plans of care should be established for each person at the end of life.

Another problem with DNR orders is that they can be perceived by families and significant others that they are giving permission to end a patient’s life. Some experts in death and dying have suggested that the term “allowing natural death” (AND) replace DNR. This newer term better describes a clearer intent and is less emotional and threatening than DNR (Venneman et al., 2008).

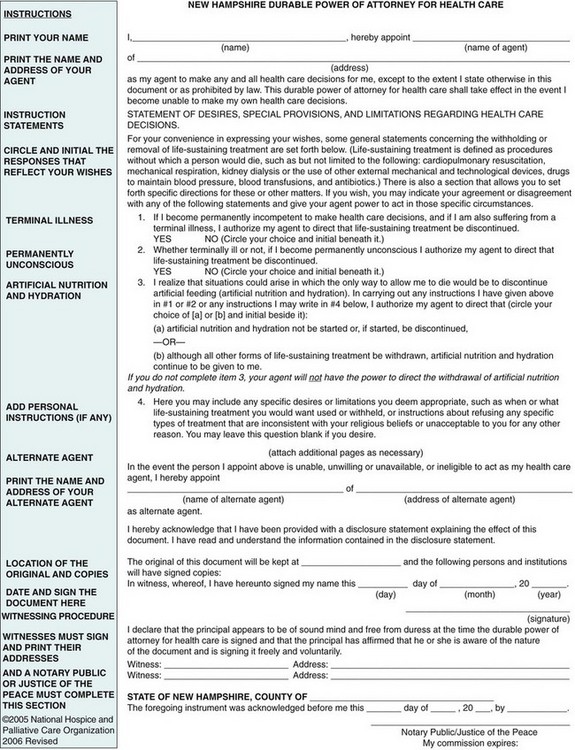

Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care

The second type of advance directive is the durable power of attorney for health care (DPOAHC). The DPOAHC is a legal document in which a person appoints someone else (e.g., health care proxy) to make his or her health care decisions in the event he or she loses decision-making capacity (Fig. 9-1).

Advance directives vary from state to state but are readily available through Caring Connections, an online program of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2005) (www.caringinfo.org). Anyone can complete the advance directive forms without legal consultation. A copy of each directive should be given to the primary health care provider and health care proxy. Remind the patients and health care proxy to keep the advance directive(s) in a secure place, such as a safe deposit box or fireproof box. Remind patients that they can change their mind at any time of their lives or at end of life.

Thomas et al. (2008) reviewed the literature on cultural preferences for advance directives. The researchers found that European Americans (whites) had a more positive attitude and more knowledge of AD than did Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, or African Americans. Possible factors influencing these differences are related to family relationships and religiosity. Non–European-American groups tend to be more family-centered and expect that family members will make the best possible decisions about the patient’s death. Many also believe that God controls when and how death will occur (see the Evidence-Based Practice box on p. 110).

What Are the Common Cultural Preferences for End-of-Life Care in Developed Countries?

While there were numerous findings, the key cultural differences were:

• European Americans (whites) were more knowledgeable and therefore had a more positive attitude about advance directives when compared with Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and African Americans.

• Non-European Americans tend to be more centered on family and religion. They trust that their families and/or God will make the best decisions about end-of-life care and the dying process.

• Patients of any ethnic group were more involved in making EOL decisions if they spoke English. Those who could speak English received better pain management and more comfort measures than non-English-speaking patients.

• Non-European groups were more likely to want family present during the dying process when compared with European Americans.

• African Americans and those older than 75 years in any ethnic group had less family to rely on for comfort and decision-making support.

Desired Outcomes for End-of-Life Care

The desired outcomes for a patient near the end of life (EOL) are that the patient will have:

Hospice and Palliative Care

The concept of hospice in the United States resulted from a grassroots effort in response to the unmet needs of terminally ill people. As both a philosophy and a system of care, hospice care uses an interdisciplinary approach to assess and address the holistic needs of patients and families to facilitate quality of life and a peaceful death (Taylor, 2009). This holistic approach neither hastens nor postpones death but provides relief of symptoms. Hospice systems of care are provided in a variety of settings. They are often affiliated with home care agencies, providing services to patients at home or in a long-term care or assisted-living facility. Some communities also have hospice houses, which provide care to patients in the terminal phase of their lives.

Signs and Symptoms at End of Life

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Near the end of life, the patient often becomes weak and drowsy, often sleeping 23 or more hours of the day. Eventually he or she can become unresponsive. As the patient’s ability to speak diminishes, it is difficult to assess his or her perception of symptoms. When caring for those who are unable to communicate their distress or needs, identify alternative ways to assess symptoms of distress. Teach family caregivers to watch closely for objective signs of discomfort (e.g., restlessness, grimacing, moaning) and identify when these symptoms occur in relation to positioning, movement, medication, or other external stimuli (Chart 9-1).

Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Common Physical Signs and Symptoms of Approaching Death