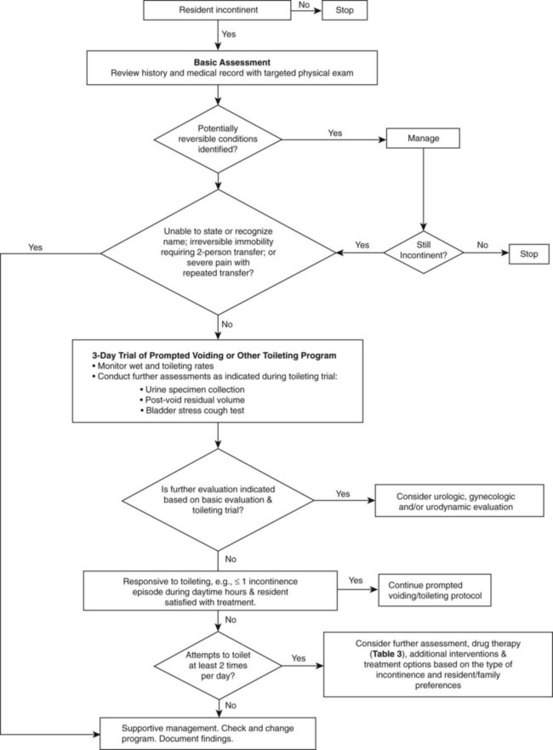

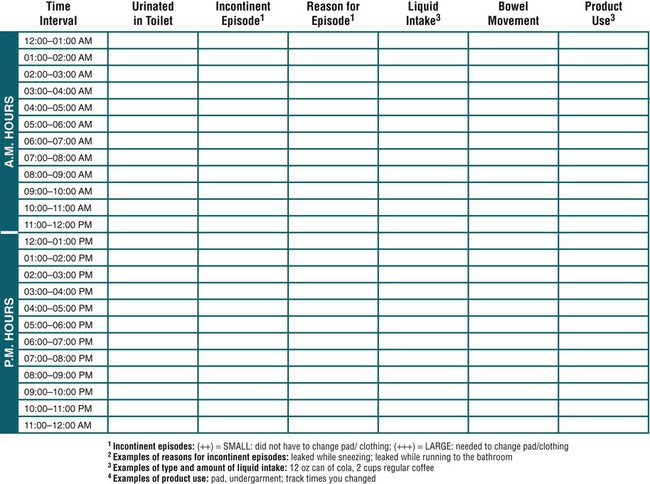

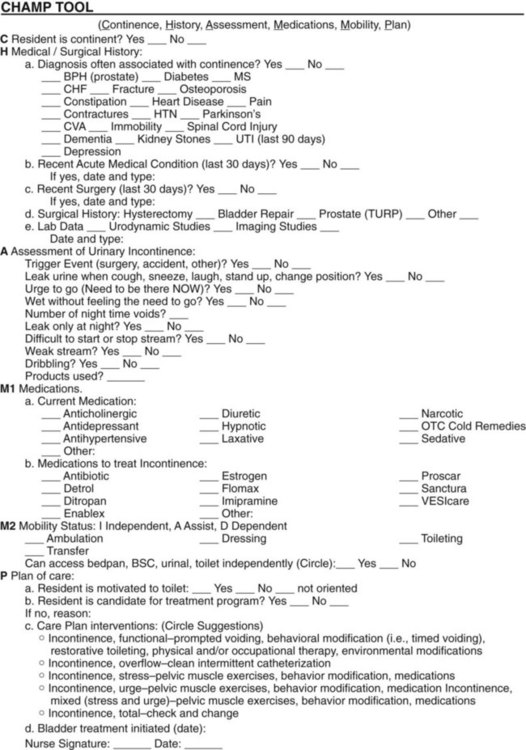

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify age-related changes that affect sleep, elimination, skin and foot care. 2. Use evidence-based protocols in assessment and development of interventions for sleep and promotion of bowel and bladder health. 3. Identify common foot and skin problems of older adults. 4. Identify preventive, maintenance, and restorative measures for skin and foot health. 5. Identify risk factors for pressure ulcers and design interventions for prevention and evidence-based treatment. This chapter addresses sleep, bowel and bladder elimination, promotion of healthy skin and feet, and prevention of pressure ulcers. The maintenance of adequate sleep patterns, normal elimination, and healthy skin and feet can be compromised in older adults as a result of aging changes and disease processes. These areas of function may often be overlooked when the focus is on management of disease or acute problems. However, insomnia, incontinence, and skin and foot problems, can be some of the most complex and challenging concerns faced by older adults, affecting health and compromising quality of life. Thorough assessment and intervention based on age-related, evidence-based protocols, is important to healthy aging and best practice gerontological nursing. Chapter 4 provides a framework for understanding changes in body systems with age. Normal bladder function requires an intact brain and spinal cord, competent lower urinary tract function, the motivation to maintain continence, the functional ability to use a toilet, and an environment that facilitates the process (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2008). A full bladder increases pressure and signals the spinal cord and the brainstem center of the desire to micturate. Social training then dictates whether micturition should be attended to or should be postponed until there is an appropriate opportunity to seek out toilet facilities. However, when the bladder contents reach 500 mL or more, the pressure is such that it becomes more difficult to control the urge to void. As volume increases, emptying the bladder becomes an uncontrollable act. Bladder changes with aging include decreased capacity, increased irritability, contractions during filling, and incomplete emptying. In about 10% to 20% of well older adults, aging of the urinary tract is associated with an increased frequency of involuntary bladder contractions (Ham et al., 2007). These changes may lead to frequency, nocturia, urgency, and vulnerability to infection. The warning period between the desire to void and actual micturition is shortened. Postvoid residual urine volume increases to 75 to 100 mL in some cases. The first urge to void occurs at a lower bladder volume (150 to 300 mL) and total bladder capacity decreases to 300 to 600 mL (Ham et al., 2007). In combination with age-related changes, illness, cognitive impairments, difficulty in walking to the toilet or in handling a bedpan or urinal, and problems in manipulating clothing can affect an older person’s ability to maintain continence. Drugs that increase urinary output and sedatives, tranquilizers, and hypnotics, which produce drowsiness, confusion, or limited mobility, promote incontinence by dulling the transmission of the desire to urinate. Urinary incontinence (UI) is the involuntary loss of urine sufficient to be a problem (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007, 2008). UI is a stigmatized, underreported, underdiagnosed, undertreated condition that is erroneously thought to be part of normal aging. About half of persons with UI have never discussed the concern with their primary care provider, and only one in eight who have experienced bladder control problems has been diagnosed. On average, women wait 6.5 years from the first time they experience symptoms until they obtain a diagnosis for their bladder control problems (Muller, 2005). Individuals may not seek treatment for UI because they are embarrassed to talk about the problem or think that it is a normal part of aging. They may be unaware that successful treatments are available. Men may be unlikely to report UI to their primary care provider because they feel it is a woman’s disease. Further research is necessary to explore the prevalence and experience of UI in men. A guideline for UI in men can be found in Box 11-1. Older people want more information about bladder control, and nurses must take the lead in implementing approaches to continence promotion and public health education about UI (Palmer and Newman, 2006). Without an adequate knowledge base of continence care and use of evidence-based practice guidelines, nursing care will continue to consist of containment strategies, such as the use of pads and briefs, to manage UI (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2008). UI tends to be viewed as an inconvenience rather than a condition requiring assessment and treatment (MacDonald and Butler, 2007). Nurses in all practice settings with older adults should be prepared to assess data that relate to urine control and implement nursing interventions that promote continence (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2008). There is a growing role for nurses in continence care and advanced training and certification are available through specialty organizations such as the Society of Urologic Nurses and Associates (www.suna.org) and the Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society (www.wocncb.org). See Evolvefor additional resources and Box 11-1 for evidence-based protocols for continence care. UI affects millions of adults worldwide. Of those who experience UI, 75% to 80% are female; the prevalence of UI increases with age and functional dependency. Estimates are that 39% of community-living older women and more than 50% of nursing home residents are incontinent. More than half of nursing home residents are incontinent on admission (Shamliyan et al., 2007; Zarowitz and Ouslander, 2007). Some evidence suggests that European American women have higher rates of moderate and severe UI compared with African American and Asian women (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007, Townsend, et al., 2011). UI is more prevalent than diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and many other chronic conditions that have prompted more attention and treatment. Incontinence is also costly; the indirect costs are estimated at more than $16 billion annually. UI costs exceed those of coronary artery bypass surgery and renal dialysis combined (Weiss, 2005; Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2008; Landefeld et al., 2008). UI is an important yet neglected geriatric syndrome (Lawhorne et al., 2008). A study on UI in nursing facilities (Lawhorne et al., 2008) reported that physicians, geriatric nurse practitioners, and directors of nursing evaluated and managed UI significantly less often than five other geriatric syndromes (falls, dementia, unintended weight loss, pain, and delirium). Nursing assistants were more likely to be involved in care provision for UI than any other syndrome and rated UI second only to pain with respect to its effect on quality of life. Reasons for less then optimal care for UI are multifactorial and include inadequate knowledge and skills about UI, inability to implement specific guidelines for UI care in nursing facilities, insufficient staffing, and poor communication among professionals and nursing assistants. Because of the high prevalence and chronic but preventable nature of UI, it is most appropriately considered a public health problem. Cognitive impairment, limitations in daily activities, and institutionalization are associated with higher risks of UI. Stroke, diabetes, obesity, poor general health, and comorbidities are also associated with UI (Shamliyan et al., 2007). Older people with dementia are at high risk for UI. For individuals with dementia, UI prevalence rates range from 11% to 90% with higher prevalence rates reflecting institutionalized patients (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007). Hospital patients with dementia are more likely than other older people to develop new incontinence. One study reported that those with dementia are five times more likely to develop new urinary incontinence when hospitalized (Mecocci et al., 2005). Dementia does not cause urinary incontinence but affects the ability of the person to find a bathroom and recognize the urge to void. Mobility problems and dependency in transfers are better predictors of continence status than dementia, suggesting that persons with dementia may have the potential to remain continent as long as they are mobile. Making toilets easily visible, providing assistance to the bathroom at regular intervals, and implementing prompted voiding protocols can assist in continence promotion for people with dementia. Box 11-2 presents risk factors for UI. UI affects quality of life and has physical, psychosocial, and economic consequences. UI is identified as a marker of frailty in community-dwelling older adults (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007). UI is associated with falls, skin irritations and infections, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and pressure ulcers, and sleep disturbance. UI affects self-esteem and increases the risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and avoidance of sexual activity. Older adults with UI experience a loss of dignity, independence, and self-confidence, as well as feelings of shame and embarrassment (MacDonald and Butler, 2007; Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2008). The psychosocial impact of UI affects the individual as well as the family caregivers. Incontinence is classified as either transient (acute) or established (chronic). Transient incontinence has a sudden onset, is present for 6 months or less, and is usually caused by treatable factors such as UTIs, delirium, constipation and stool impaction, and increased urine production caused by metabolic conditions such as hyperglycemia and hypercalcemia. Iatrogenic (or treatment-induced) incontinence is a type of transient UI that results from the use of restraints, limited fluid intake, bed rest, or intravenous fluid administration. Use of medications such as diuretics, anticholinergic agents, antidepressants, sedatives, hypnotics, calcium channel blockers, and α-adrenergic agonists and blockers can also lead to transient UI (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007, 2008). Urge incontinence (overactive bladder) is defined as involuntary urine loss that occurs soon after feeling an urgent need to void. Overactive bladder is a syndrome that overlaps with urge UI. With overactive bladder syndrome, individuals have urinary frequency (more than eight voids in 24 hours), nocturia, urgency, with or without incontinence (Zarowitz and Ouslander, 2007). The bladder muscles are overactive and cause a sudden urge to void—the “Gotta Go Right Now” syndrome (Bucci, 2007). Defining characteristics of urge UI include loss of urine in moderate to large amounts before getting to the toilet and an inability to suppress the need to urinate. Frequency and nocturia may also be present. Postvoid residual urine reveals a low volume. Urge UI is the most common type of urinary incontinence in older adults (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007, 2008). Stress incontinence (outlet incompetence) is defined as an involuntary loss of less than 50 mL of urine associated with activities that increase intraabdominal pressure (e.g., coughing, sneezing, exercise, lifting, bending). Stress UI is more common in women because of short urethras and poor pelvic muscle tone. Stress UI occurs in men who have experienced prostatectomy and radiation. Postvoid residual urine is low (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007, 2008). Functional incontinence refers to a situation in which the lower urinary tract is intact but the individual is unable to reach the toilet because of environmental barriers, physical limitations, or severe cognitive impairment. Individuals may be dependent on others for assistance to the toilet but have no genitourinary problems other than incontinence. Older adults who are institutionalized have higher rates of functional incontinence (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007, 2008). Functional UI may also occur in the presence of other types of UI. Mixed incontinence is a combination of more than one urinary incontinence problem, usually stress and urge. Mixed UI is the most prevalent type of UI in women (Shamliyam et al., 2007). With increasing age, older women with stress UI begin to experience urge UI. Continence must be routinely addressed in the initial assessment of every older person, yet many older people do not bring up their concerns about incontinence, and many health professionals do not ask. Health care personnel must begin to change their thinking about incontinence and acknowledge that incontinence can be cured. If it cannot be cured, it can be treated to minimize its detrimental effects. Nurses are often the ones to identify urinary incontinence, but neither nurses nor physicians have been particularly aggressive in its management. “Nurses have long been the providers of personal hygiene information for those entrusted to their care. Therefore, it is essential that nurses play a leading role in assessing and managing UI. . . ” (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007, p. 7). To begin assessment, screening questions such as “Have you ever leaked urine? If yes, how much does it bother you?” are suggested (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2007). Assessment is multidimensional. It includes a health history, targeted physical examination (abdominal, rectal, genital), urinalysis, and determination of postvoid residual urine. For women, evaluation of the reproductive system and gynecological history and examination is recommended since gynecological factors may contribute to the urological problem. More extensive examinations are considered after the initial findings are assessed. Individuals who do not fit a simple pattern on UI should be referred promptly for urodynamic assessment (Ham et al., 2007). A thorough health history should focus on the medical, neurological, gynecological, and genitourinary history. It should should include functional assessment, cognitive assessment, psychosocial effects; strategies currently used to control UI; a medication review of both prescribed and over-the-counter drugs; a detailed exploration of the symptoms of the urinary incontinence; and associated symptoms and other factors. In care facilities, an environmental assessment including the accessibility of bathrooms, room lighting, and the use of aids such as raised toilet seats or commodes is also important. A link to a video of a nurse performing an assessment to evaluate transient incontinence can be found in Box 11-1. In the nursing home, continence is assessed with the Minimum Data Set (MDS), and the MDS 3.0 provides a comprehensive overview of the assessment, treatment, and evaluation of bladder and bowel continence based on the new Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines (Johnson and Ouslander, 2006). All newly admitted nursing home residents should have a thorough assessment of continence status as well as ongoing evaluations during their length of stay. The CHAMMP (Continence, History, Assessment, Medications, Mobility, Plan) tool (Bucci, 2007) was developed by a certified wound, ostomy, and continence nurse to guide comprehensive continence assessment and implementation of individualized plans of care in nursing homes (Figure 11-1). Figure 11-2 presents a guide for diagnostic assessment and management of UI in the nursing home setting. One of the best ways to establish the presence of and describe incontinence problems is with a voiding diary. This is considered the “gold standard” for obtaining objective information about the person’s voiding patterns and the UI episodes and their severity (Dowling-Castronovo and Bradway, 2008, p. 314) (Figure 11-3). The voiding diary can be used by both community-dwelling and institutionalized elders. Older adults in the community can usually keep a bladder diary without much difficulty. Bladder diaries for those in long-term care are usually maintained by the staff and are used in conjunction with a trial of individualized, resident-centered toileting programs. The character of the urine (color, odor, sediment, or clear) and difficulty starting or stopping the urinary stream should be recorded. Activities of daily living (ADLs), such as ability to reach a toilet and use it and finger dexterity for clothing manipulation, should be documented.

Elimination, Sleep, Skin, and Foot Care

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Bladder Elimination

Bladder Function

Age-Related Changes

Urinary Incontinence

Prevalence of UI

Risk Factors for UI

Consequences of UI

Types of UI

Promoting Healthy Aging: Implications for Gerontological Nursing

Assessment

BPH, BSC, bedside commode; benign prostatic hyperplasia; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVA, cardiovascular accident; HTN, hypertension; MS, multiple sclerosis; OTC, over the counter; TURP, transurethral resection of the prostate; UTI, urinary tract infection. (From Bucci A: Be a continence champion: use the CHAMMP tool to individualize the plan of care, Geriatric Nursing 28:123, 2007.)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree