On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Explain how health care is financed in the United States. 2. Briefly explain the history of Social Security and some of the anticipated challenges. 3. Compare the types of health care services available under Medicare. 4. Describe the differing levels of decisional capacity and their implications in gerontological nursing. 5. Differentiate the types of elder mistreatment. 6. Identify persons at risk for abuse or neglect. 7. Describe strategies that may be used to minimize the risk for elder mistreatment. 8. Identify the nurse’s legal responsibility in his or her own home state when neglect or abuse is suspected. 9. Describe the role of the nurse-advocate in relation to legal, health, and economic issues of concern to the older adult. Before the industrial revolution of the late 1800s, persons in most countries and cultures worked until they were no longer physically able to do so. In many cases the “work” of the individual changed with time and as capabilities diminished, and it did not cease until shortly before death. Family members and the community provided care when necessary (Bohm, 2001). It was not until the rigors of industrial work that opportunities disappeared for those with declining abilities. In the mid-1800s, the term retire was defined as “withdraw from service” but changed to mean “no longer fit for service” in the early 1900s. Care became less available as whole families joined the urban workforce. Congregate living, including nursing homes, and Social Security as a form of ongoing income for eligible workers were created as a result of the social changes of the time. In the early 1900s, almshouses and poor houses emerged to provide care for frail indigent persons who did not have family available or able to care for them (see Chapter 1). Most of these facilities were supported by charitable organizations. Later, the government became involved, and when the primary population in almshouses was the elderly, many essentially became public nursing institutions. In some places the law supported the use of public monies for a formerly private purpose (care of the elderly), and local governments were authorized to purchase land and erect facilities for the care of the elderly and could tax its citizens to maintain them. In the early 1900s, it was determined that the care of indigent elderly could be construed to be a public responsibility. Because the concept of personal responsibility continued to exist, poor persons who were admitted to care facilities were required to contribute any property they owned that could be used to help pay for the care and maintenance provided. Considered by many to be one of the most successful federal programs, Social Security was established in 1935 in the depths of the Great Depression. The primary function of the program was to provide monetary benefits to older retired workers and was viewed as a means to prevent or minimize the dependency of older members on younger members of society (Weinberger, 1996). Social security and a number of programs that followed were set up as “age-entitlement” programs. This meant that an individual could receive the benefits simply because of their age and regardless of their need. In other words, the monetary support is available to those persons at a certain age regardless of their personal resources. The benefits, however, were and still are limited to American citizens and legal residents older than a certain age, or who are totally and permanently disabled and have paid into the Social Security program, or who are married to someone who has done so. Social Security is a major source of income for those who are 65 and over (Figure 20-1). The program has been managed on what is called a pay-as-you-go system. Payroll taxes on a percentage of income are collected from employees and employers and are immediately distributed to beneficiaries (retirees and the disabled or eligible spouses) in the form of income and health services. Social Security funds, although individually deposited by employers and employees, are not reserved for any one individual. No one has an account set aside in his or her name. All funds that are not immediately paid out to beneficiaries are “borrowed” by the federal government for regular operating expenses. The government converts the borrowed funds into government bonds, reflecting the debt of the government to Social Security, and places these in a “trust fund” watched over by the trustees of the fund. However, no funds are specifically identified to pay back those monies borrowed from the Social Security Trust Fund (Weinberger, 1996). Details of the changing status of Social Security (and Medicare) are provided to the public annually and may be accessed at www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/index.html (Trustees, 2010a). The amount of income one will receive at the time of retirement and each year thereafter depends on the age at retirement and the amount of contributions. The return is not of the investments specifically but on a calculation based on the number of “credits” paid into the system. The amount needed for a credit increases automatically each year. For example, in 2010 workers received a credit for each $1090 earned up to 4 in any one year. In general, a person has to have earned 40 credits to take advantage of the benefits of Social Security. For the current cohort of older adults, this calculation has been most beneficial to white men, who are more likely to have worked the most consistently and at higher salaries than all other groups of workers. A cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) increase had occurred each year there was a corresponding increase in the Consumer Price Index. However, due to the down turn in the U.S. economy there was no COLA in 2011. In 2010, the average Social Security benefit was $1164 for the 57 million recipients with a maximum Social Security benefit of $2346 and a minimum of $0 (Social Security Administration [SSA], 2010). Finally, financing late life may include private retirement or pension plans. Individuals may pay into the plans themselves (e.g., IRAs) or through their employers (e.g., 401K accounts). The private retirement, pension funds, or a combination of these are invested in private sector financial instruments (e.g., stocks, bonds, or real estate holdings) or perhaps in government treasury notes. Those funds are held for the beneficiary and may become part of his or her estate if the beneficiary dies before collecting the pension. Some private retirement annuities provide for several choices for receipt of funds after retirement. The retiree could elect to take his or her pension based on his or her own life only or based on the retiree’s and a spouse’s life. In other words, a person may set up a plan so that he or she receives all or most of the benefit during his or her lifetime rather than providing for any survivor benefit. Notification of the potential survivor of such a choice is not always required (Hooyman and Kiyak, 2008). The amount received is actuarially determined based on the life expectancy of one or two beneficiaries and whether a guaranteed minimum number of years are selected. In the United States, health care has always been a purchased service—not a right (Figure 20-2). It is primarily purchased either directly or indirectly through an insurance plan of some kind with the cost of the plan directly proportional to the benefits provided. The federal government purchases the majority of care through its insurance plans (Medicare, Railroad Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE) or provides it directly through the Veterans Administration. State governments are also significantly involved through the shared Medicaid plan and in public and mental health services. The major insurance plan available to older adults living in the United States is Medicare. Persons without insurance purchase all health care in an “out-of-pocket” manner. They are expected to pay whatever the charge is for a received service. Although the number of uninsured persons is expected to increase each year, most elders fall under one of the safety nets of Medicare, Medicaid, or both. In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed the Committee on Economic Security (CES) to craft a Social Security bill. The original report included a health insurance plan, but because of much opposition to it, Roosevelt deferred the health insurance part of the bill to avoid losing Social Security (see earlier discussion) (Corning, 1969). The American Medical Association opposed any national program of health insurance, believing it to be “socialized medicine,” and made efforts to prevent its implementation (Goodman, 1980). Fortune magazine polled the American public in 1942 and found that 76% of those polled opposed government-financed medical care (Cantril, 1951). In the early 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson recognized that the numbers of older persons, those with serious disabilities, and poor children were increasing significantly and that often these vulnerable groups were without access to needed health services. Although opposition continued, Johnson proposed amendments (Title XVIII and Title XIX) to the Social Security Act to address these social problems. In Senate and House hearings, some legislators described the amendments as steps that would continue to destroy independence and self-reliance and would tax the poor and middle class to subsidize the health care of the wealthy (Twight, 1997). Nonetheless, legislation was passed in 1965 and 1966 to expand the Social Security system by establishing Medicare, Railroad Medicare (for retired railroad workers), and Medicaid. Medicaid’s criteria included income and asset restrictions. In a short time after implementation of these plans, millions more persons could receive health care, and the costs for the services escalated rapidly. Prescription drug coverage in the form known as Medicare Part D was not added until U.S. President George W. Bush’s administration in 2006. The Affordable Care Act of the Obama administration (2010) contained a number of provisions with potential impact designed to improve health care services for older adults. These provisions are expected to be enacted over a period of years, however significant changes remain possible due to opposition to the legislation (AARP, 2010). Medicare is an insurance plan for persons who are age 65, blind, or totally disabled, including those with end-stage renal disease. It combines the age-entitlement Medicare A with purchased B (Original Plan), C (Advantage Plans), and D (Prescription Plan). When one enrolls in Medicare, one selects the type of coverage and the premiums as one does with any other insurance plan. Medicare Part A was created to cover the costs of hospital and limited nursing home care (Box 20-1). Medicare Parts B & C were created as a purchasable and affordable voluntary insurance plan that covered outpatient and health care provider services in the forms of (1) fee-for-service, (2) preferred provider, and (3) managed care plan. Medicare Part D is a prescription drug plan. Medicare is administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and is a part of the Department of Health and Human Services, a special entity created to improve the administration of the programs. In 2009, nearly 47 million persons were covered by some part of Medicare with total expenditures of $509 billion (CMS, 2009). In 2010, major changes in Medicare were made into law through the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Through roughly 165 provisions, the ACA will reduce costs by decreasing payment rate while at the same time reducing fraud and increasing coverage for preventive services and research (Trustees, 2010b). The impact of these changes remains to be seen. Medicare Part A is a hospital insurance plan covering acute care and acute and short-term rehabilitative care and some costs associated with hospice care and home health care under certain circumstances. Those qualified automatically receive a Medicare card (red, white, and blue) indicating Medicare Part A coverage when he or she becomes eligible to receive Social Security income. Those who have not paid an adequate amount into the U.S. Social Security system may be eligible to purchase Part A coverage for a monthly fee ($450 per month in 2011). Coverage begins the first day of the month of eligibility. The coverage and co-payments vary by setting under the original fee-for-service plans. When acute care is needed, the co-payments can be quite high, especially for stays of over 60 days. The initial deductible is $1132 (as of 2011) with no co-insurance until day 91 when it is $283 per day for days 61 to 90 each benefit period. After the 90th day, a person begins using “lifetime reserve days”—up to 90 at $566 per day (CMS, 2011). Rehabilitative care, usually provided in skilled nursing facilities, is paid for only if it occurs within a set time from a hospital discharge and as long as the patient requires what is called skilled care (only that which is provided by a licensed nurse or physical or occupational therapist). Medicare Part A will pay 100% of the first 20 days of a nursing home stay, with a co-pay of up to $141.50 per day for days 21 to 100 and no coverage after that (CMS, 2011). At any time the person no longer needs skilled care, Medicare coverage stops. Medicare does not cover additional charges that may be incurred during a long-term care stay, such as incontinence supplies or laundry. Hospice services (see Chapter 23) are usually provided in the home; for which there are no co-pays or deductibles. If short term respite or inpatient stays are necessary for the comfort of the patient or family support there is a 5% co-pay. In the 7 months surrounding a person’s 65th birthday (from 3 months before), all persons who are eligible for Medicare Part A must select and apply for Part B or Part C (see below) through the Social Security Administration (www.socialsecurity.gov). Medicare Part B covers the costs associated with the services provided by physicians; nurse practitioners; outpatient services (e.g., laboratory services); qualified physical, speech, and occupational therapists. Beginning in 2011, most deductibles and other cost-sharing of preventive care has been removed, and the one-time-only wellness checkup has been replaced with an annual covered exam (Whitehouse, n.d.). The advantages of the Original Medicare Plan include choice and access. Participants can seek the services of any provider they choose and do so without a referral. While the numbers are diminishing, providers all over the United States accept Medicare, and participants can change providers as often as desired. With the Original Medicare Plan, the patient is responsible for an annual deductible, co-pays, coinsurance charges, and a monthly premium. In 2011, this was $115.40 a month for persons with incomes of $85,000 or less as an individual or $170,000 or less as a family. The premiums rise gradually to $369.10 with incomes up to $214,000 individual and $428,000 family. The annual deductible was $162 (CMS, 2011). Otherwise referred to as Medicare Advantage Plans (MAPs), Medicare Part C uses a prospective payment plan and include traditional health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and managed care plans. All traditional services covered by Medicare Part A and Part B must be provided, and additional services, co-pays, and deductibles are predetermined. Medicare Advantage Plans may or may not also provide prescription drug benefits; if so, they are referred to as MAP-PDs. Not all MAPs are offered at all locations in the United States. Those that have been granted Medicare per capita waivers cannot refuse applicants based on pre-existing health conditions. MAP premiums vary in price depending on location and range of services. The elder is referred to the Medicare website for more information or a counselor available through senior organizations (www.medicare.gov). The premium is in the form of a “capitated” payment. The MAP receives a set amount on a monthly or quarterly basis regardless of service use for each member enrolled and regardless of the amount of care given. All necessary care must be provided from this amount. The MAP assumes all of the liability for costs incurred for the care of the member based on the plan. This model has created abuses and horror stories in which elders were denied needed treatments to save money for the corporate providers. Patient protection laws now allow consumers to lodge complaints and initiate legal action against these abuses. The Center for Patient Advocacy supported a much-needed bill that became law in October 1999 (www.biapa.org). This law allows appeals when a MAP denies care, guarantees access to specialists when needed, ensures that health-related decisions are made by health care providers rather than bureaucrats, and holds the plans legally accountable for medical decisions that cause harm. The PDPs established under Medicare Part D are all commercial plans that have contractual arrangements with CMS. To be included as an option, the company must agree to follow the rules set forth by CMS and change as directed. With the agreement to provide the minimum level of benefits established by Medicare Part D regulations, the plan is deemed “credible” by the CMS and becomes accepted as equivalent (Stefanacci, 2006). Like other insurance plans, once enrolled in either Medicare Part D or another credible PDP, a person cannot change a plan until the next open enrollment period except under special circumstances. These circumstances include those who are admitted to, reside in, or are discharged from a skilled nursing facility and persons with dual-eligibility. Different than other plans, if the person does enroll in Medicare Part D at the same time as enrolling in Medicare Part B, late enrollment penalties are charged. Persons can change their plans during the “open enrollment” periods each year. Most PDPs are set up in a similar way. Deductibles, co-pays, gaps, and limits are dependent on the premiums paid, ranging from about $25 to about $100 with an annual deductible of $250. After the person had spent $250, the PDP covered 75% of the cost of the approved drugs up to $2000, with a 25% co-pay (Medicare paid $1500, the person paid $500). The next $2850 in costs was paid directly by the individual (called the “donut hole”). When the total costs for approved drugs reached $5100 ($3600 out-of-pocket), the PDP paid 95% (5% co-pay) of all drug costs for the rest of the year. The premiums and co-pay amounts are expected to change annually and vary greatly from plan to plan. The deductible and donut-hole are repeated yearly. More than 8 million elders reached this “donut hole” or gap in 2007. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 attempted to address this, first with a rebate of $250 when the hole is reached, and beginning in 2011, pharmaceutical companies agreed to institute a 50% discount on brand name drugs purchased during that time (Whitehouse, n.d.). Although most PDPs have donut holes, a person may elect a plan with lower co-pays or broader drug coverage for a higher monthly premium (CMS, 2010). Because of the potentially high co-payments associated with Medicare, persons who are able to do so often purchase supplemental insurance plans. These feature standard benefits, and generally several different policies are available from which to select in each state. Persons searching for an appropriate plan can be referred to the Medicare website for their state or can request a printed copy of the standard plans (available at www.medicare.gov). Plans referred to as Medigap cover only the deductibles and part of the co-insurance amounts based on Medicare-approved amounts contracted with providers. Other sources of insurance coverage are through employee benefit offices (e.g., covered under COBRA) or organizations such as the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). Physicians and nurse practitioners who agree to accept the Medicare assignment amount can collect the uncovered percentage (e.g., 20%) from the secondary insurance. In some parts of the country (and for some persons), alternative health plans for older adults are available, such as Indian Health Services for anyone who is a documented member of one of the Indian Nations or Medicare Railroad or care through demonstration programs or Programs of All Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) (see Chapter 16). TRICARE is a Medigap policy provided by the Department of Defense for Medicare-eligible beneficiaries ages 65 and older and their dependents or widows or widowers older than age 65. This plan requires that the person enroll in both Medicare Part A and Part B and pay the premiums for Part B. As a Medigap policy, TFL covers those expenses not covered by Medicare, such as co-pays and prescription medicines. Dependent parents or parents-in-law may be eligible for pharmacy benefits if they turned age 65 on or after April 1, 2001, and are enrolled in Medicare Part B. For more information about this, see www.tricare.osd.mil.

Economic, Legal, and Ethical Issues

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Finance in Late Life

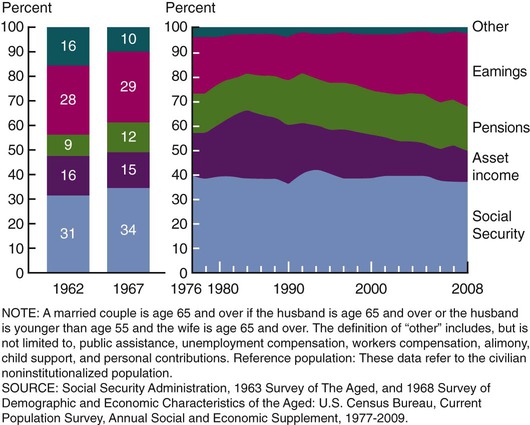

Social Security

Other Late Life Income

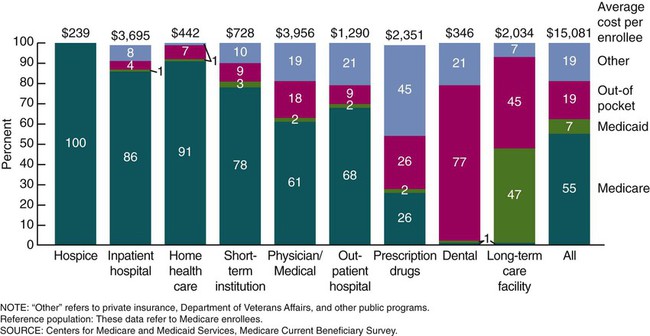

Paying for Health Care

Medicare

History

Overview

Medicare Part A

Medicare Part B

Medicare Part C

Medicare Part D

Supplemental Insurance/Medigap Policies

Care for Veterans

TRICARE for Life

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Economic, Legal, and Ethical Issues

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access